| Wu Ding 武丁 King of Ancient China | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait of King Wu Ding of Shang from Sancai Tuhui (三才圖會) | |||||||||||||

| King of Shang (1600 - 1046 BC) | |||||||||||||

| Reign | c. second half of the 13th century BC | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Xiao Yi | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Zu Geng | ||||||||||||

| Chancellors | Gan Pan (甘盘) Fu Yue (傅說) or Hou Que (侯雀) | ||||||||||||

| Born | c. first half of 13th century BC Kingdom of Shang | ||||||||||||

| Died | c. 1200 BC Yin, Kingdom of Shang | ||||||||||||

| Burial | Tomb M1400, East Zone, Xibeigang Royal Cemetery, Yin, Kingdom of Shang | ||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||

| Issue | Zu Ji (祖己), "Expectant King" (小王) Zu Geng (祖庚), Prince Yue (曜) Zu Jia (祖甲), Prince Zai (載) Xiao Chen Tao (小臣妥), Princess Tao (妥) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Father | Xiao Yi | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Shang spiritual religion Jitian | ||||||||||||

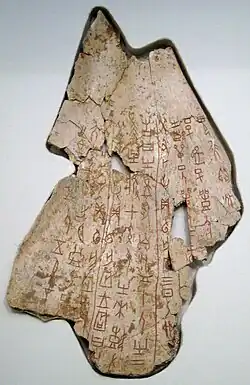

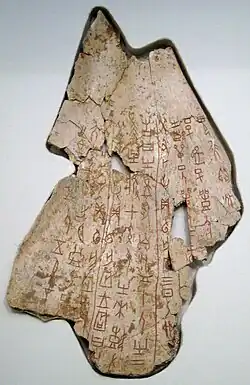

Wu Ding (Chinese: 武丁; pinyin: Wǔ Dīng) (died c. 1200 BC); personal name Zi Zhao (子昭), was a king of the Chinese Shang dynasty who ruled the central Yellow River valley around the second half of the 13th century BC. He is the earliest figure in Chinese history mentioned in contemporary records. The annals of the Shang dynasty compiled by later historians were once thought to be little more than legends until oracle script inscriptions on bones dating from his reign were unearthed at the ruins of his capital Yin (near modern Anyang) in 1899.[2] Oracle bone inscriptions from his reign have been radiocarbon dated to 1254–1197 BC ±10 years,[3]: 165 closely according with regnal dates derived by modern scholars from received texts, epigraphic evidence, and astronomical calculations.[3]: 172

Wu Ding's reign is considered one of the most prosperous period of early ancient Chinese civilization. Spanning from the mid 13th century BC to the early 12th century BC, the era saw the appearance of the earliest Chinese writing as well as technological developments. Ancient Chinese culture flourished, and, through its religious and artistic aspects, left an important legacy. The spiritual beliefs along with social structure from his reign passed down to the Zhou dynasty, which would later embrace and further develop them into unique features of classical Chinese society. It was also this time that the Shang kingdom increased their territorial extent greatly, and experienced one of the most glorious time in the second millennium BC. Due to successes in wars with neighboring tribes and annexation of dependent chiefdoms, the Shang expanded away from its heartland and increased its influence on once-distant tribal peoples. Wu Ding and his two reigning sons maintained the dynasty's power before it went down rightafter, and were revered as one of the exemplary monarchs of ancient Chinese civilization.

The time frame which defines Wu Ding's ruling era is of crucial importance to the study of Chinese history. His reign is considerably more notable than previous Shang kings in terms of historical evidence (larger number of artifacts, constructions, and contemporary written records). As a result, modern studies about the Shang dynasty mark his period as the beginning of the late Shang, with the era itself represents the first phase. (See also Shang dynasty#Kings)The time assigned with his reign is frequently used by historians to construct the timeline for the Shang dynasty. His family's graves together with their possessions were found at his seat in Yin, illustrating the reality of a dynasty that was previously perceived as legendary.

In classical Chinese historiography, Wu Ding is often depicted as a meritorious king. Major ancient records about him include the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) of Sima Qian, the Classic of History, and the Bamboo Annals. Other texts about his rule are minor ones like the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips. The narrative of Wu Ding in Zhou traditional history books features elements of the Mandate of Heaven (and the associated concept "Son of Heaven") which only appeared two centuries after Wu Ding's time. He appeared in various conversations as the Son of Heaven, being addressed by his relatives and ministers. Zhou romanticization of his life, although having misinterpreted Wu Ding as being influenced by their ideology, has the effect of portraying him as a model of an ancient virtuous ruler of a kingdom. Generally, the description of Wu Ding's regnal period in classical histories could in some way attest to his written oracle records, especially the identity of the ministers.

Dating

Because Wu Ding is the earliest Chinese ruler whose reign is confirmed by contemporary material, dating his reign is a matter of significant historical interest. He is by far the most studied Shang monarch regarding the time periodization, since the time frames are frequently used in determining the ruling eras of other kings (though he is the first one verified, it is historically proven that many generations of the Shang had ruled before him). Various sources propose different time frames, and the exact period has not been confirmed.

According to the traditional chronology, he reigned from 1324 BC–1266 BC.[4] This has been shown to be an artifact of incorrect backdating due to misunderstanding of King Wen of Zhou's Mandate calendar.[5][6] In the Records of the Grand Historian, Han dynasty scholar Sima Qian wrote of his reign as beginning in the year dingwei (丁未), which can be either 1333 BC or 1273 BC according to the ganzhi calendar's 60-year repetition. The Guben Zhushu Jinian ("ancient version" of Bamboo Annals) gives Wu Ding's regnal dates as 1273–1213 BC.[7] The Cambridge History of Ancient China gives 1189 BC as the end date of his reign based on records of lunar eclipses.[8] The Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project draft release (2000), sponsored by the Chinese government and disbanded without producing a final report, gives his reign as 1250–1192 BC.[9] Inscriptions from twenty-six oracle bone divinations of his reign have been radiocarbon dated to 1254–1197 BC ±10 years.[3]: 165 It is important to note that the methodology of the radiocarbon investigators involved accepting uncritically the purported reign length of 59 years attributed to Wu Ding in the transmitted record.[3]: 165 The assigned 59-year length was given by non-contemporary records of the king, and therefore may not be error-free.

Before the twentieth century CE, archaeologists had not found any firm evidences for the Shang dynasty's existence. Since 1899 CE, the Ruins of Yin began to be excavated, and the period's historicity was verified. Nevertheless, because of the differences between the time frames given by ancient Chinese historical records, the exact dates of events that took place in Wu Ding's reign could not be determined. Instead, the events (wars, religious affairs, etc.) are presented using the according ordinal years in each texts. In particular, the texts take the years as ranging from Wu Ding's first year of reign to his 59th year, which is the final end of the period. Many events were recorded as happening when he had ruled for over twenty years, while others took place at his reign's beginning. In spite of the time frames' variety, it is probable that the events documented happened after the 1250s BC, the time near which the classical books place Wu Ding's assumption of the throne.

The Bamboo Annals (竹書紀年) is the classical text that provides the most detailed information on Shang chronology. Not only does the book assign the years concerned but it also records days and months in traditional calendars. It has a complicated and murky transmission history, looted by grave robbers in the early Western Jin, with the original text lost early. Modern historians who rely on the Annals disagree when determining the Shang dates. Preceding the Shang was the Xia, whose traditional rules of successions are uncertain due to the absence of the dynasty's written records. David Nivison argued that each of the Xia kings' reign had relations with his filial mourning periods, and that Jie of Xia's 31-year reign length was imaginarily made up by Warring States editors.[10] Those are thought to have caused discrepancies between the Bamboo Annals' dates and modern time verification. 1273 is the first Wu Ding year proposed by the text. Using the rules and features of ganzhi with period modifications, sinologists have proposed specific dates for Wu Ding, which are significantly used in calculating his birth and death. Their results suggest the first Wu Ding year around 1250 BC, which agrees with radiocarbon dating's outcome. Alternative sources of dating often resort to using the Shang dynasty's astronomical records. The Shang (and Zhou) were aware of numerous extraterrestrial events and believed that they were portents of the rulers' death; texts that date from late Wu Ding era had lots of information concerning the aspect. However, this method is usually only effective in deciding deaths, since astronomical phenomena were linked with bad forthcoming happenings.

Life and reign

Early life

The Shang dynasty practiced royal succession using a form of agnatic seniority, at times distributed across multiple lines of descent.[11]: 198–199 In the generations preceding Wu Ding, succession had been split between the descendants of Zu Yi (祖乙) through his two sons Zu Xin (祖辛) and Qiang Jia (沃甲).[12] This was interpreted by later historians as a weakening of an incorrectly reconstructed system of primogeniture.[13] The Shang kings immediately preceding Wu Ding were three of his uncles (including the famous Pan Geng, who moved the capital to Huanbei)[14] and finally his father, Xiao Yi. By the custom of the time, Xiao Yi could potentially have been succeeded by one of his second cousins from the alternate royal line.[lower-alpha 2] The fact that Xiao Yi was able to place his son on the throne despite the claims of a rival lineage may explain why Wu Ding built a new capital for the second time in living memory, as well as the transmitted tradition that he was sent away from the capital during his father's reign.[16]

Wu Ding was the 11th-generation descendant of Tang of Shang (成湯) (c. 1600 BC) in the main line of descent. His origin and ancestry are detailed in oracle records. His ancestral surname was "Zi" (子), the surname of his 24th-generation ancestor Xie[17] and one of the most frequently mentioned surname in China in the second millenium BC (during the Shang dynasty, few people carried surnames). After the Shang dynasty, Zi was exclusively a title for rather than a surname; this usage may have been the intent during the Shang dynasty as well, since the character can mean "master" or "prince".[18] He was given the personal name "Zhao", which means "bright" and "luminous".

He happened to be Xiao Yi's only son, and therefore was created crown prince. The Bamboo Annals carry an entry stating that in the sixth year of his father's reign, Wu Ding was ordered to live at He (河) (ancient name for the Yellow River). Gan Pan (甘盤), a prominent minister in Xiao Yi's court, was chosen to be Zi Zhao's tutor. A late chapter in the Shangshu asserts that during these early years, he worked together with the local peasants. The times spent among the common people allowed Wu Ding to become familiar with their daily problems, which affected the ruling method of the future king.[19]

King of the Shang dynasty

Around 1250 BC, Xiao Yi died after reigning for approximately 30 years. However, the Bamboo Annals suggests a 10-year reign, which is dated by Nivison to have begun in xinwei January 24th, 1260 BC or 1263 BC.[20] This result implies that Wu Ding's education as a crown prince began around 1254 or 1257 BC, the sixth year of Xiao Yi.

Zi Zhao succeeded his father as king. His regnal name later became known as "Wu Ding" (武丁). This is due to the naming tradition of the Shang dynasty, which is based on its calendar (appeared in the late 14th century BC). The system followed a list of ten Heavenly Stems used to denote 10 days in a Shang week: jia (甲), yi (乙), bing (丙), ding (丁), wu (戊), ji (己), geng (庚), xin (辛), ren (壬), gui (癸).[21] In some sources, he is believed to have ascended in the dingwei year. The Celestial Stem "ding" (the fourth one in the classical arrangement of ten) might be the reason for his regnal name being "Wu Ding". The other character, wu (lit. "martial"), was used to distinguish himself from other two Shang kings that shared the same ding name, his grandfather Zu Ding (祖丁) and 6th-generation ancestor Zhong Ding (仲丁) (later, there would be two more rulers that used the stem as their regnal name, Geng Ding and Wen Wu Ding). The name was only in use after his death. In the Wade-Giles romanization, the name is transcribed as "Wu−Ting".

Wu Ding's date of accession to the throne is uncertain. However, it is reasonably believed that the became king most possibly on January 4th, 1250 BC, as some researches into the Bamboo Annals have pointed out. It is indicated from the Bamboo Annals's entries that he succeeded his father in the day "dingsi" of the year "dingwei" (both repeats with a 60-unit period). The Shang succession traditions also followed a pattern that the new kings assumed power at the beginning or the end of a (Julian converted) year.[20] Using the information and through suitable year changes, David Nivison calculated Wu Ding's first day of reign as January 4th, 1250 BC or 1247 BC.[20] Nivison also argued for another reason that Wu Ding chose his regnal name ding, that is, the first day of the year 1250 BC (converted into the ganzhi calendar) began with a "ding" day.[20]

Wu Ding assumed power over the Shang territory during its period of instability and wane. His first royal ancestors were supposedly able to establish and develop the state's superiority over surrounding peoples. During the reign of his ancestor Tai Wu (around the late 16th and early 15th century BC), the capable ruler had cultivated strong connections with ancient tribes and brought them into Shang cultural sphere.[22] Over the years, the non-Shang peoples were brought under domination. However, before Wu Ding inherited the kingly title, the Shang dynasty had already declined.[23]The generation before him has four male members, who all became monarchs. Starting with Yang Jia (陽甲), the Shang kingdom gradually lost its dominance in northern and central China as well as once-dependent tribal ethnicities. Using the opportunity, the dynasty's enemies retook their lost lands, thus reducing its territory. Although Pan Geng (盤庚) later briefly restored the state,[23] it fell again into weakness when his brother Xiao Xin (小辛) took the position.

In Sima Qian's Shiji he was listed as the twenty-second Shang king, succeeding his father. The oracle bone script inscriptions unearthed at Yinxu alternatively record that he was the twenty-first Shang king.[24][25] The Shiji says that he was enthroned with Gan Pan (甘盤) as his prime minister and Yin (殷) as his capital. In the exceptionally long period of 59 years, Wu Ding's reign marked the transition of the Shang dynasty from a declining, local power into the "late Shang", a prosperous kingdom that reassured its influence over China proper. As his kingdom was separated from other major civilizations, it became the dominant power in the Yellow River valley and the Yangtze River basin. Although his ruling period was characterized with wars, traditional Chinese historiography still portrayed him as a virtuous monarch who showed great care to his country. Chapter XXI of the Book of Documents describes him remaining silent in the beginning of his reign as to cultivate his virtue.[26] According to the text, Wu Ding restrained himself from speaking even after his three-year mourning for his father's death (during which all the state affairs were discussed and managed by his court ministers) had ended:

The king passed the season of sorrow in the mourning shed for three years, and when the period of mourning was over, he (still) did not speak (to give any commands). All the ministers remonstrated with him, saying, 'Oh! him who is (the first) to apprehend we pronounce intelligent, and the intelligent man is the model for others. The Son of Heaven rules over the myriad regions, and all the officers look up to and reverence him. They are the king's words which form the commands (for them). If he do not speak, the ministers have no way to receive their orders.' On this the king made a writing, for their information, to the following effect: "As it is mine to serve as the director for the four quarters (of the kingdom), I have been afraid that my virtue is not equal to (that of my predecessors), and therefore have not spoken."

(By referring to the anecdote, classical historians have emphasized on his righteousness, filial piety and the desire to be an upright ruler like his predecessors.)

Aside from war, his relations with other peoples were also maintained through peace acts. He cultivated the allegiance of neighboring polities by marrying one woman from each of them. Oracle bone inscriptions mention no fewer than sixty-four of his wives;[27]: 464 another tally counts over one hundred.[28] His favoured consort Fu Hao entered the royal household through such a marriage.[29] As the Shang religion prioritized boys, he was allowed to have as much wives as possible in order to increase the number of male children, as they would continue the reigning lineage.

According to the Bamboo Annals, in the twenty-fifth year of his reign, his son Zu Ji (祖己) died at a remote area after being exiled. His mother (possibly consort Fu Hao) predeceased him. Zu Ji was the first male child of Wu Ding.

Residence

Since 1600 BC, the capital of Shang was changed and relocated many times. The recorded sites chosen as capitals are Bo 亳 (modern Caoxian 曹縣, Shandong), Ao (隞) (modern Xingyang 滎陽, Henan), Xiang (相) (modern Neihuang 內黃, Henan), Geng (邢) or 耿 (modern Xingtai 邢台, Hebei or Wenxian 溫縣, Henan), Bi (庇) (modern Yuncheng 鄆城, Shandong), Yan (奄) (modern Qufu 曲阜, Shandong).[30] From Wu Ding, the capital was settled in one city that aroused as the dynasty's center for the rest of its timespan. Wu Ding is verified to have chosen the ancient city Yin (constructed around the year 1300 BC) as the state's capital. The question about whether Yin was only the capital from Wu Ding's reign onward remains uncertain. The Book of Documents and the Bamboo Annals assert that the city had previously been established as capital since the time of Pan Geng (c. 1300 BC), while Sima Qian's Shiji proposes a different site of the same period (late 14th century BC - early 13th century BC).[22] Some other sources claim that around 1300 BC, Pan Geng did not move to Yin but to a nearby site that was later abandoned and replaced. The site excavated at Huanbei in 1999 is generally acknowledged to be the capital of Pan Geng.[14] Regardless of the inconsistencies, it is pointed out that Yin was clearly the Shang capital in the time of Wu Ding. The city was regarded as the kingdom's center, and methods of determining the direction of surrounding neighbors all took it as a base. Specifically, the tribes' locations were referred to as "northwest of Yin", "east of Yin", etc.

Yin was probably the largest urban area of the Shang dynasty since its founding. Its current archaeological remains cover a large area of 30 square kilometers, encircling many royal palace complexes. An early example of mass urbanization in China, the city housed members of the elite, including the king's family, central authorized officials and the diviner-shamans. The city was the political and cultural center of the kingdom from Wu Ding's period to the final years (1050s BC), with the majority of writings and artifacts belonging to his time (tens of thousands of oracle bones were concentrated in Yin). It additionally served as a base for the Shang armies, namely the royal troops who were tasked with protecting the court and the capital. The royal cemetery, which contained tombs of nobles and royal members, was also located in the area. From 1899 CE, archaeological excavations have revealed the ancient settlement of Yin, providing deep insights into the Shang dynasty (and Wu Ding, who is known for reigning in the time which began the verified historicity of Chinese traditional chronology). Inside the area lie numerous artifacts, oracle bones and bronze products containing writings, and remains of the Shang royal constructions (palaces, tombs, temples). It is this site that provides archaeologists and historians the materials to study the historical culture and life of Wu Ding along with his succeeding generations.

The ancient city's name was initially Beimeng (北蒙). Pan Geng, upon moving to it, renamed it to Yin (殷). Because it was the capital of Shang for over 250 years (1300 - 1046 BC), the corresponding half of the dynasty (late Shang) is often called the "Yin dynasty" (However, all the oracle bone inscriptions address the state as "Shang".[17] The Shang name for the city was not "Yin", which was a later name used by the Zhou dynasty. Alternatively, Shang oracle bones call the area "Great Settlement of Shang" (大邑商; Dàyì Shāng). There were urbanization in other provincial regions; however, as Wu Ding's inscriptions point out, they were only towns that might possibly have had protecting walls. Wu Ding appeared to have had no residence located in local regions.

Court life

Obvious signs of social divisions are shown in Shang period, particularly the time from 1300 BC when archaeological materials were present and agree with written records. Thanks to the first texts in Chinese dating back to Wu Ding, his reign is the first period that historians can have a general understanding of everyday life. The life of common people (mostly peasants) was typically somewhat challenging, but that of the aristocracy and the royal family was luxurious. That is because both of the two stood in the highest point of Shang social pyramid. He governed the country mostly from the capital, although he occasionally took tours around the state. To administer far regions, orders were issued and sent to local lords. Though he was the king, he did not actually hold absolute power, but instead bestowed governing authorization to close people. The succeeding dynasties of the Shang left virtually no record that helps imagine its court life; instead, they are known through contemporary oracle documents, as well as plenty of archaeological items. Those records give the most details on Wu Ding's court life, which involved relatively new aspects compared to previous kings.

As a king, Wu Ding unsurprisingly belonged to the most elite class, and thus enjoyed a much more comfortable life than the majority of Shang people at that time. His new seat in Yin consisted of palaces and monumental constructions, which had been built not long before since the city had recently been inhabited. The Shang core lands lay on the fertile soil supplemented by the Yellow River; therefore, the productivity level was high. He possessed a portion of agricultural products, which at that time consisted primarily of millet (the staple crop of ancient China for centuries). There are other crops of which he possibly owned portions, such as wheat and rice, the products made in private fiefs of his relatives. A percentage of those crops' harvest was probably used by the aristocracies as tributes to him.[31] The king also had access to the then-valuable materials like silk, a handicraft industry developed earlier, and bronze, which at that time was only approachable by the wealthier classes. Wu Ding made extensive utilizations of bronze; the material was specifically used widely in weapon-making to provide instruments for the forces, and was also utilized in making hunting equipment. Alternatively, the metal was utilized in bronze-made artifacts: Wu Ding possessed a large number of vessels that remain to the present day.[32] Jade, despite its rareness, was present. Wu Ding's queen Fu Hao was interred in her grave along with over 750 decorated jade products.[33]

The use of animals in different purposes was prevalent and considered necessary during this period. Hunting was a common activity, and was used as a means of getting meat sources. Some of the animals were obtained through royal hunts; it was often tigers, buffaloes, deer, foxes, and birds that were desired. Fishery developed, playing a role in supplying aquatic animals. On the other hand, in Wu Ding regnal era, animal husbandry developed essentially to produce needed resources. Horses appeared in his time, largely due to the rising demand for them. The Shang began to domesticate horses and train them to draw chariots around the period of 1250 - 1200 BC. Domestic species (sheep, pigs and dogs), apart from being consumed, were used by the court to sacrifice together with humans; oracle scripts record large numbers of animals being sacrificed, thus indicate the importance of their use to Wu, who was deeply religious. According to traditional sources, Wu Ding enacted policies in order to prevent excessive animal sacrifices, thus save the meat source (See § Participation in Shang religious activities).[34] There are evidences for the presence of larger animal species, for example elephants. The animal was mentioned several times in oracle bones (the pictograph for it resembles a vertical rotation of the elephant's image). Excavations of Tomb M1400 in the Shang royal cemetery in 1935 unearthed parts of an elephant's skeleton.[34] The tomb was constructed during the same time with the Tomb of Fu Hao (see § Women in government), i.e. built in Wu Ding's late years of reign.[35] It is additionally believed that ivory was widely used and treated as a decorative material.[34]

Wu Ding employed significant manpower to join the workforce. He made several construction plans, most of which were tombs and graves for his relatives. He had thousands of workers-often captured males from surrounding ethnicities-at his disposal and usually used their labor in carrying out the buildings. There are not plenty of evidences for the use of internal farmers in the labor force, but it existed: some of Wu Ding's relatives recruited farmers to work for their personal land or protect the regional borders. Others were expected to serve as shepherds or caretakers of horse stables.[34][36] When a royal member died, it was a tradition for them to be sacrificed and buried in their designated graves. The workers composed a large proportion of Yin's population. The Shang dynasty is often perceived by Marxist historians as an example for slave societies; however, the nature of people laboring in the period is not fully understood and therefore unable to be determined. Nevertheless, it is true that Wu Ding and his court made effective use of unpaid labors. But the workers were not fully exploited since he did not completely subdue other countries, and so did not get their total manpower. His later descendants were recorded as employing a larger number of workers after their states had been merged into Shang.

Participation in Shang religious activities

The Shang dynasty practiced one of the first well-established religion in early ancient China, which-as indicated by oracle bone scripts-focused primarily on worshipping spiritual beings in exchange of welfare and happiness. Since he was deeply religious, practice of Shang beliefs became an indispensable part of court life. He took part in many worshipping rituals, and was helped by several diviners whose work was to write questions and make the cracks on the material by heating. Wu Ding's religious activities was recorded in oracle bone inscriptions as offerings to Di (high god of Shang), as well as sacrifices to his royal ancestors who were deified as protectors and prosperity givers of the state. Apart from writings, artifacts also played a role in Shang religion at that time. Excavations at Anyang have discovered numerous artifacts that were used in religious activities. A large proportion of them were made of bronze, which was rare and only accessible to the priests or nobles. Other components include mud (pottery) and stone. The products featured carves of supernatural spirits and were used regularly in ceremonies.

Later Chinese historians when referring to him tended to stress on him attending ceremonies through romanticized anecdotes. According to the Book of Documents, in the twenty-ninth year of his reign, he conducted rituals in honour of his ancestor Da Yi (大乙), the first king of the Shang dynasty, at the Royal Temple. When he saw a crowing pheasant on one of the ceremonial bronze vessels, he became frightened and considered it an ominous omen. Zu Ji, who was accompanying his father during the rituals, is said to have thought "'To rectify this affair, the king must first be corrected." Following this thought, Zu decided to discuss the omen with his father. He was quoted as saying: "In its inspection of men below, Heaven's first consideration is of their righteousness, and it bestows on them (accordingly) length of years or the contrary. It is not Heaven that cuts short men's lives; they bring them to an end themselves. Some men who have not complied with virtue will yet not acknowledge their offences, and when Heaven has by evident tokens charged them to correct their conduct, they still say, "What are these things to us?" 'Oh! our Majesty's business is to care reverently for the people. And all (your ancestors) were the heirs of the kingdom by the gift of Heaven;−−in attending to the sacrifices (to them), be not so excessive in those to your father." After Wu Ding heard this, he reformed the sacrificial system by critically reducing the number of sacrifices. In order to comply with the rules of the new changes, offerings to the Shang ancestors avoided luxuriousness. Wu Ding supposedly wrote a proclamation called "Day of the Supplementary Sacrifice of Gaozong".(高宗肜日).[37] The Book of Documents passage in question is attributed to Zu Ji; that contradicts with the records in the Bamboo Annals, which assigns Zu Ji's death four years before the 29th year of Wu Ding's reign. The difference reflects a different tradition of vital dates for that individual.

Because the Book of Documents was composed during the Zhou dynasty, the narrative of the conversation above was done according to the dynasty's religious beliefs. The use of the word "Heaven" (Chinese: 天 "Tian") by Zu Ji in his quote was due to it being the Zhou's concept of the highest deity. The Shang dynasty believed in another supreme being, Di ("帝", or alternatively called "Shangdi"). After the Zhou replaced the Shang, the god Di was embraced by Zhou and gradually became identical to Tian. Therefore, the concept "Heaven" in the anecdote does not in any way correspond with the religious traditions of the court at the time.

Another two religious aspects that Wu Ding was actively involved was divination and sacrifice. The king, with the assistance of his priests, was responsible for a large proportion of oracle bone divinations found at Yin. Wu Ding specifically divined about his queen, both when she was alive and after her departure. In particular, one inscription on Fu Hao's being pregnant said that the conception was "inauspicious" (that the child was a girl).[38]. Aside from pregnancy, he also divined on her health, prosperity, as well as praying for her in the afterlife. (He is believed to have married her three more times to his ancestors, since he believed they would act as her guardians after death). He also asked divinatory questions on human sacrifice as well as warfare. He also seemed to be in awe of his ancestors, especially his second uncle Pan Geng. He regularly wrote questions on weathers, agricultural issues for his deceased predecessors, and he held a thought that they were capable of indirectly supporting his army in battles.[39] Moreover, Pan Geng was specifically perceived to be involved in his nephew's health. One example based on contemporary records is a reconstructed ceremony by Keightley, which aimed to seek improvement for Wu's dental problems.[39] In the ritual, Wu Ding offered one dog and one sheep to Pan Geng and tried to convince him to treat his toothache. The example illustrates Wu Ding's belief in the supernatural-ancestral causes of health issues.

Contrary to the rituals/ceremonies told by the Zhou with uncertain elements, Shang divination itself was verified by the dynasty's own writings. The texts in oracle bones often include the names of diviners. Wu Ding particularly divined exceptionally many times; numerous bone texts feature the king himself as the chief diviner. He interpreted the cracks on oracle bones to predict future events, of which four notable examples are:[40]

- Crack-making divination on the day guiwei: Wu's assistants predicted no disaster, but he divined that the near future would be misfortune. It is purportedly said that six days after, a relative of Wu died. The relative was possibly Zu Ji, although the texts do not specify his identity. He allegedly died in wuzi day of the First Month.[40]

- Another time, he interpreted the signs as negative. It is said that eight days later, the Sun was covered by large clouds, and a rainbow appeared in the Yellow River.

- Divinations on wars and territorial defense: on the day guisi, Wu Ding predicted the opposite future from his diviners that confrontational polities were going to launch attacks on his border. In the day dingyou, it is believed that bad news came from the West by an entrusted regional lord, Guo.[40] The lord reported that Tu Fang had attacked the territory and destroyed two towns, and another tribe had taken over the kingdom's western fields. However, this is somewhat contradictory, since Tu Fang supposedly mobilized its men from the east, contrary to their being located northwestern of Yin.

- A prognostication of disasters gave the outcome that one of Wu Ding's accompanying ministers would fell off his chariot during a hunting expedition. The misfortune occurred on jiawu day, when the king was seeking for rhinoceros. Two person, one of his xiaochen (petty minister) and his child fell off their chariots.

The above oracle divinations differ notably from others due to the inscriptions' unusual length and presentation. They were carved in extraordinary large characters on bones. Some oracle analysts, including David Keightley, suggest that such carves are "display inscriptions" which were carved to illustrate the monarch's power with particular strength and thus used for recopying and further reading.[40] However, several other scholars argue for an alternative reason, that is the oracle scripts which contain the information above might not have been real divination records of Wu Ding, but alternatively practice texts written by him to be copied by scribes that were still training the job.[41]

The divinations of the scribes often included the prediction of fortune in a certain period (usually a Shang week). An ox scapula records thư divinations by Zhēng (爭), one of the Bīn (賓) group of diviners serving Wu Ding. On the piece of bone, four separated divinations were carved (either by the king or Zheng himself):

- On the top: 卜,☐,貞[旬]亡𡆥。"... divined: In the next ten days (week), there will be no disasters."

- On the left: 癸卯卜,爭,貞旬亡𡆥。甲辰☐大掫風,之曰皿,乙巳[疛]𰙫(止幸)☐五人。五月在[𦎧]。 "guǐmǎo (day 40) Zheng divined: in the next ten days there will be no disasters. jiǎchén (day 41) ... strong gale, evening cleaved to yǐsì (day 42), captured ... five people. Fifth month, in Dun."

Ox scapula recording divinations by Zhēng 爭 in the reign of King Wu Ding

Ox scapula recording divinations by Zhēng 爭 in the reign of King Wu Ding

- On the middle: 癸丑卜,爭,貞旬亡𡆥。王(占)曰:有祟,有夢。甲寅,允有來艱。左告曰:有往芻自(皿),十人又二。 "guǐchǒu (day 50) Zheng divined: in the next ten days there will be no disasters." The character 王 (king) indicates the personal involvement of Wu Ding in this specific divination. Wu Ding added to Zheng's conclusion that there would be ominous spirits, and on the day jiayin there would be obstacles.

- On the right: 癸丑卜,爭,貞旬亡𡆥。三日乙卯[有](壴女)艱,單邑豊[尿]于彔……丁已貍子豊尿……鬼亦得疾。 "guǐchǒu (day 50) Zheng divined: in the next ten days there will be no disasters. Third day, yǐmǎo (day 52) ... dīngsì (day 54) ... The Gui will also have sickness." "The Gui" here might refer to the Guifang tribe.

Wu Ding's royal family, predictably, also played a part in religious practice. They appeared to have been granted their own authorization of exercising power as priests, and some oracle texts carved by the assistants might have been made in the service of the princes.

The majority (70%) of oracle characters date back to Wu Ding's reign, which indicates his emphasis on his religion.

State administrative organization

Shang society was practically a monarchical polity. There were citizens divided into four social classes: royal members and nobility, artisans, military officials and craftsmen (peasants were not considered). The Shang king was regarded the head of the state, holding considerable power. The religious practices of the dynasty consisted of a pantheon, mixed between gods and honored ancestors. The kings considered themselves descendants of supernatural beings: in the Shang pantheon there existed a spirit recorded in oracle bones as "Kui".[39] The oracle pictograph depicting him has the shape of a bird. Kui is often identified by history analysts as Emperor Ku, one of the Five Emperors; in later histories, Tang of Shang was said to have descended from Emperor Ku, which indicates the Zi family as having divine powers. Wu Ding, upon ascending to the throne, became the political and religious apex of the social pyramid.[39] Overall, he directly involved himself in military, and acted as a commander. Regarding religion, he played the role of a chief priest, and communicated with the deities through the rituals. Other state affairs such as economic management was partly concerned by him; he dealt with the problems together with the civil officials in the court. As Shang's economy was based on agriculture, Wu Ding appeared to be particularly aware of the farmer's harvests (Some of his carved writings are questions asking the gods about whether the peasants' crops were successfully collected).

The central government, mentioned occasionally on contemporary records, showed signs of categorization. The Shang dynasty consisted of various court positions as assistants of the king. According to the 20th-century scholar Trần Trọng Kim, the Shang dynasty had 25 governmental positions: two "xiang" (二相), six "tai" (六太), six "gong" (六工), six "fu" (六府), and five "guan" (五官).[42] The roles of each position, however, were not mentioned. Apparently, its official system was not as well-organized as the later Zhou dynasty. The court was not divided into fully specialized departments like in subsequent Chinese dynastic eras. The individuals appointed as officials, or ministers, were not restricted to a certain aspect but qualified to handle various state affairs with the ruler. The small functionaries were known as xiaochen, and were tasked with supervising field ploughing, managing laborers and shepherds, or be responsible for the horse stables.[31] There were also positions of supervising construction works. The inevitable importance of religion during his time led to more religious official titles. There were over 70 diviners active at his court, known as "duobu" (多卜), that worked with the scribes ("zuoce" 作冊).[31] The process of choosing people for those positions was done by divination, yet there were some rudimentary beginnings of an impersonal form of organization of the government, even if it was still organized in a flexible and unsystematic way. In Wu Ding's time, the ministers were headed by a chief (or a chancellor).

Wu Ding's relatives (wives and offspring) were given certain governmental positions. However, later historians (the composers of the Shangshu, for example) usually include anecdotes about non-relative central ministers that assisted Wu Ding, and therefore emphasised on the king's court as being essentially meritocratic. In fact, the narrative describes Wu's officials to be highly capable people, despite the fact that the chapters only concern the highest-ranking ones among them. Their real talents as well as their role in the court are still incompletely comprehended.

Classical records of the first chancellor Gan Pan

It is believed that two individuals were chosen as administrative chancellors by this king. Several texts state that after becoming king, Wu Ding appointed his former tutor, Gan Pan (甘盘), as the chief minister at his court. Gan began to arrange military formations of the country while also acting as an adviser to the new ruler. In the work "Shangshu Zhengyi", Kong Anguo mentioned Gan Pan as an exemplary minister that could be compared with Yi Yin. The Book of Documents makes the same analogy in its chapter on the Duke of Shao, who would act as one of the Three Regents under King Cheng of Zhou approximately 250 years after Gan Pan. In the text, the Duke of Zhou is quoted as delivering a lesson about Shang meritorious officials that ought to be viewed as models of loyal and capable ministers:

The duke said, 'Prince Shih (i.e. Duke of Shao), I have heard that aforetime, when Tang the Successful had received the appointment (to the throne), he had with him Yi Yin, making his virtue like that of great Heaven; that Tai Jia had (the same Yi Yin)" [...] "through whom his virtue was made to affect God, and Wuxian who regulated the royal House" [...] "and that Wu-Ting had Kan Pan (Gan Pan). These ministers carried out their principles, and displayed their merits, preserving and regulating the dynasty of Yin, so that, while its ceremonies lasted, (those sovereigns), when deceased, were assessors to Heaven, and its duration extended over many years.

Views on the second chief minister Fu Yue

According to Kong Anguo's source, Gan Pan died shortly after Wu Ding inherited the throne. After his death, the chancellor position was replaced by Fu Yue (傅說) (alternatively called Fu Shuo). The Records of the Grand Historian and the Shangshu contain paragraphs mentioning the story of Wu Ding encountering Fu Yue. According to the source, Wu Ding was informed by Heaven that he would receive a man named "Yue" who would assist him in governing the country. After waking up, he consulted his court but no one recognized the man. Therefore, he produced a painting of the man from his memory and dispatched his troops to seek for the person. Yue was found as a worker at a defense construction; his appearance was said to perfectly match the description of the desired person.[43]Seeing that Yue was intelligent and learned, Wu Ding appointed him as his chancellor and gave him the

surname "Fu" (lit. "teacher") after the name of the place he was working. The Book of Documents includes a chapter about Fu Yue discussing with his monarch about state affairs. The conversation involves Wu Ding consulting Yue about his concern on how to effectively rule over a kingdom, which he took the two rulers Yao and Shun as examples. The king expressed his desire to be a rightful ruler; he compared Fu Yue with Yi Yin, speaking of him as the one who could make Wu Ding like another Tang. Fu Yue delivered a lesson on virtues for a decent monarch, then promised that he would support the king in building his personal image.

The story contains heavy mythological flavors, and has elements of romanticization for emphasizing the virtue and righteousness of the two persons involved. However, it is indicated that Fu Yue was practically a historical character. Based on information on the oracle bones, historians have constructed a list of ten court officials at the time of Wu Ding's reign: Gan Pan, Hou Que, Wangcheng, Jun He, Jichen, Jian, Qin Dian, Xi Li Zhi, Cang Hou Hu, Hou Gao. It is thought that Fu Yue was likely to be identical to Hou Que: in fact, several oracle bones describing Hou Que handling affairs that were very similar to those of Fu Yue mentioned in the Tsinghua Bamboo Slips as well as other texts.[44] Hou Que, similar to the romanticized Fu Yue, had an important part in Wu Ding's assistants. (The list, however, remains controversial because necessary information about many of the ten individuals included are yet to be found.)

Several central officials serving under him played a role in his campaigns of expansion. Two officials, Zhi and Hou Gao, were known for their military campaigns with Fu Hao. The two commanded the Shang royal army, heading thousands of troops to engage with the tribes Yi, Qiang and Ba.[45] However, their military operations appear to have been restricted to the Shang's northwestern and western neighboring areas, in which lies the major long-term enemies of Wu Ding. Contemporary inscriptions also record the names of over six hundred females that took part in discussing state issues, similar to the role of male ministers.[46]

Governance of provincial-level regions

As Wu Ding achieved greatly in his expansion schemes, his rule was established on a much larger area than that of his ancestors. However, the king's control of regions that were farther from Yin was practically nominal. Ruling from modern-day Anyang, the monarch was unable to protect the most vulnerable lands of his state. The primitive conditions of transportation also proved an obstacle to his ability to immediately respond to urgent situations in remote lands. That led to the fact that he had to resort to the strategy of sharing power with other people. He divided the country into portions which served as autonomous lands. Unlike the central governing body which only included a certain number of people who controlled court affairs and central military, regional administration was performed by numerous local lords of varied backgrounds. Wu Ding did not himself establish this system, since it had been used centuries before him. The general term for the dependent lords is duohou (多侯) (precursor of the Zhou dynasty term "zhuhou"). They were given personal lands and expected to give tributes, portions of harvest, and military support to the Shang monarch, a practice similar to the system used by later dynastic regimes. Many royal members (principal wives, princes and princesses) were enfeoffed as regional lords with considerable authority. The words tian, dian and nan (田 "field" plus 力 "plough/force") show that each of these lords was allowed to control a certain number of arable fields.[31] Non-relative vassals of the king were often granted farther territories. Obedient lords were accepted as trustable allies of the central government and were given nobility titles.[31] A notable chief is Guo of Zhi, mentioned several times in contemporary texts;[40] he was apparently an ally and a chief of Wu Ding's distant lands. In two inscriptions, Guo of Zhi is recorded to have merged his local troops into the central army, which-at that time commanded by Wu-was mobilizing to battle. This system of provincial-level controlling is still incompletely understood, but is to some extent a predecessor of the fengjian system used by the Zhou dynasty centuries later in which the monarch devolved local power onto regional leaders. Nevertheless, it was less effective in ensuring the allegiance of most vassal leaders, since it did not rely on any central concept like fengjian to deify the Shang king's image and rectify his right to rule. Consequently, is was difficult for Wu Ding himself to gain trust and alliance of his own subordinates. Usually, the vassals refuse to pay tributes and did not send military supports in times of internal struggles. Wu Ding (and his uncle Pan Geng), unlike many other kings, was successful in stabilizing the country and ensure the vassal's loyalty to him.[31]

War and conquest of opposing polities

During his time (c. 1300 BC - c. 1200 BC), the Shang kingdom was isolated from other few advanced civilizations. Surrounding the country were tens of social polities organized into tribes and chiefdoms. The connection status between the dynasty and its neighbors was different regarding both time and the neighbors' locations, but overall many of them constantly engaged wars with Shang. Wu Ding, having had the newly advanced technologies and methods, succeeded in winning over his enemies and bringing the country back to its once lost hegemony in China proper. More lands were gradually ceded into Shang and the tribes were vassalized , thus assimilated into its culture. It is important to note that because the neighboring peoples appeared to have no writing systems, all the known records containing information about relationships between two sides were created by the Shang and its successor Zhou. The connections presented in the Shang oracle bones as well as Zhou historical texts have probabilities to be subjective accounts given by one-sided writers. It is true that many polities mentioned in Wu's contemporary writings exist and that the Shang under his leadership gained considerable territories by numerous military achievements, but the people who recorded them might have exaggerated.

Military structure and equipment during Wu Ding's period

Although little is known about military arrangements during the king's reign, their armies contributed significantly to the kingdom's warfare and defense. The central government disposed of 3 regiments: zhongshi (中師), zuoshi (左師), youshi (右師). These were used to defend the royal domain as well as secure the new territories gained. In order to defend border regions, the royal troops (wangshi 王師, woshi 我師) were sent and garrisoned in remote regions. Wu Ding's court also had military conscriptions reserved for dangers. They were called "deng" (登) or "zheng" (征) (conscripts), and were trained to react to urgent situations such as enemies' attack of the capital. However, such conscriptions were still rare during the Shang dynasty, and records of them are few. The royal force numbered at thousands and were militaristically trained during royal hunts. The royal servants were able to be promoted to official positions by taking part in battles.[47]

The royal seat of the Shang kings at Yinxu wasn't protected by walls but by a moat.[47] The moat at Yin has a total length of 8000 meters, with a width varying from 7 to 21 m and depth around 10 m. It encircles a large area of 2.4 square kilometers.[48] It served as a means of defense together with the troops locally stationed.

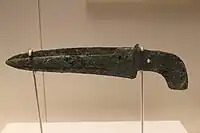

The Shang armed forces employ a wide range of weapons and supporting equipment. Troops had both bone and bronze weapons, including máo (矛) spears, yuè (鉞) pole-axes, gē (戈) pole-based dagger-axes, composite bows. At the time of Wu Ding, bronze weapons became widely distributed in the kingdom, both in the capital and provincial regions; in the preceding periods, they appeared in smaller numbers. Weapons found in Shang royal tombs reveal an advanced bronze metallurgy that makes the instruments more useful in utilization than in the reign of previous rulers.[49] Soldiers also possessed defensive instruments such as bronze and leather helmets.[50]The presence of chariots in Wu Ding's period gave the forces an advantage over other chiefdoms and tribes. According to literary sources, a chariot was drawn by more than one

horse, and accompany 3 people with swords, halberds, and bows. However, chariot remains excavated at Anyang indicate that one chariot could only contain one person.[47] The chariot was probably used in commanding.[51]

The army overall was good at organization and mobilization. The Shangshu contains a chapter describing the arrangement of an infantry: it relied on the decimal system, with a large unit consisting of ten smaller ones (however, the troops were mainly sacrifices as they were buried with their deceased king).[47] Leaders of tribes submitted to the court were stationed at their land; they had their local land to guard regularly, as the submitted lands often lay in the border with other opponents. Local troops, known as "fangguo jun" (方國軍),[47] were to protect the region while also joining combats with royal armies while necessary. The regions' chiefs were obliged to prepare both his manpower and weaponry for forthcoming battles: peasants could be recruited into the army to increase the strength of regional troops. In his battles, Wu Ding would personally lead a group of thousands of troops to support the regional troops.[52] His reign witnessed continuous conflicts between Shang and its opponents, which surrounded the kingdom in all directions. That led to the necessity of employing large numbers of soldiers in order to effectively counter the other sides' warriors. With the application of this distributing method, Wu Ding was able to ensure his forces's strength during battles.

Major campaigns against hostile tribes and chiefdoms

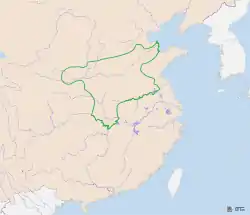

It is essential to note that during the control of the Shang dynasty, territorial extent was not well established as later regimes. For example, the Zhou dynasty during most of its years had defined borders that were recorded. However, the lands gained by Wu Ding's army did not always actually belong to his kingdom. The continuous switch between friendliness and hostility of Shang's neighbors resulted in remote regions that remained nominally under rule of the court but actually controlled by the local leaders that were appointed as governors of their conquered lands. Instead, those lords were connected with the Shang through means of influence, by commissioning envoys and sending tributes. The king and his court could be described as a large governing system , while the post-conquest polities were brought under their influence but not directly ruled. The approximated area of the Shang; therefore, is currently not defined. Opinions vary, with some sources taking the state's borders as its maximum reach of suzerainty.[53] Some maps have Shang territory encircling the lands of Predynastic Zhou, which around 1200 BC did not have sufficient contacts with Wu Ding.

Northwestern and eastern expansions

The relations between the Shang kingdom and neighboring polities varied during the reign of preceding kings. Oracle bone inscriptions dating back to Wu Ding mention a wide range of unstable connections with tribes and chiefdoms, generally addressed as fang (方).[54] Several tribes made alliance with Shang while others remain aggressive and confrontational. Regarding the resources that he could utilize at the time, Wu Ding's military strength was considered superior to his enemies'. The Shang had both better weaponry and mobility. What is more, Wu Ding's expanding campaigns mainly aimed at occupying lands previously inhabited by tribes that had less complicated military structures and more simple equipment. That contributes to the fact that Wu Ding was able to defeat his enemies. The Shang writings say that after their surrender to Wu Ding, several tribes and chiefdoms ensure their survival by being allies of Shang; they received the annexed lands to govern and entrusted to protect the borders. Nevertheless, some of them did not keep the relations for long.

Oracle bone scripts record that the Shang dynasty maintained contact with Guifang (鬼方), a chiefdom northwest of Yin that was sometimes interpreted as "unfriendly" to the central region. According to the Bamboo Annals, the thirty-second year of Wu's reign, he sent troops to counter Guifang, stationing the army at Jing (荊). After three years of fighting, he conquered it and annexed it into the kingdom, turning Guifang into his supporters in expeditions against other foes. The Di (氐) and Qiang (羌) immediately sent envoys to Shang to negotiate. Exactly how this is related to the campaigns in the oracle bone divinations is unclear: the Guifang appears only once, while the Gong Fang and Tu Fang campaigns have hundreds of divinations. The Tu Fang tribe, in particular, had been at war with the Shang dynasty for generations before Wu Ding, but they were defeated in a large battle during his reign. Hundreds of oracle inscriptions record more distant tribes and chiefdoms that remain in conflict with Wu Ding. An example was a tribe named "工" which formed an alliance with Tu Fang in order to resist Shang.[55] The tribe was accordingly located in the central of modern Shaanxi; they maintained their independence until Zu Geng's reign, decades later Wu Ding. A wide range of other northwestern states were mostly mentioned by name. For example, it is stated that Renfang (人方) in the east was once conquered by Wu Ding's generals. This Renfang tribe was once the subject of Wu Ding's prognostication. Specifically, he once divined that on a sacrificial day, he would lead his troops to join Lord Guo of Zhi in countering Renfang, and asked for the deified spirits to indirectly support him.

Interpreting the relations of the late Shang dynasty at Yin with northwestern frontier and dependent tribes employs many oracle bones, as later compiled books did not guarantee full accuracy. Most of the scripts were carved by Wu Ding and his scribes, providing valuable information about the historical existence of the polities. The Shang apparently faced with various tribes, some of which have been identified with earlier researched settlements. Guifang was probably the most mentioned people, having been inscribed not only by the Shang dynasty but also by the first kings of the Zhou dynasty. The Guifang was studied and has often been identified with other northern polities with different ethnonyms. For example, Wang Guowei came to the conclusion that Guifang was the same people as the Xunyu, Xianyun, Rong and Di tribes.[56][57][58] Additionally, the Guifang is believed to have belonged to an ancient nomadic group later known as Xiongnu (匈奴).

An alternative suggestion for the ethnicity of Guifang is that they were identical with the Seima-Turbino culture.[59] The conclusion resulted from several excavations in Yinxu , which revealed artifacts that bear strong resemblance with the culture's identity. Interestingly, the artifacts were dated to the time that Wu Ding's forces were reported to be fighting against Guifang. Perhaps the tribe was actually an eastern group of people from Seima-Turbino that came into conflict with the Shang kingdom, which led to exchanges of products.[59]

The hostility of those polities towards Wu Ding is also in question. Apparently, the Guifang was described in his oracle bones to be hostile and sometimes friendlier. However, the oracle bones do not contain information on the battles between Shang and Guifang. This contradicts with the Bamboo Annals, in which Wu Ding's schemes to invade Guifang's land are detailed. The inconsistency leads to the question that whether Guifang engaged in wars with Wu Ding or it was himself who launched expeditions first. One fact that is confirmed is the aftermath of the battles. According to oracle inscriptions, Guifang submitted to Wu Ding, and allowed the king to merge the region into Shang's domain. Some individuals of the polity even acted as assistants in the court, through participation in everyday affairs. For instance, a Guifang native that Shang named "Geng" joined the group of Wu Ding's sacrifice supporters; he was expected to perform a type of sacrifice in the xiang (亯) ancestral temple. Guifang's warriors were as well recruited into the military. The Qiang people, another neighbor, had been at war during the same time with Guifang's surrender. After being crushed by Wu's 13,000-men army, some of the most confrontational Qiang people retreated and attempted to wage wars again. Wu Ding made use of the submitted Guifang men to strengthen his manpower.

Tu Fang, another large tribe, also attracts Chinese scholars' attention. It was quite powerful, and its wars were recorded in Shang writings. Tu Fang was eventually defeated, however, and became Wu Ding's subjects. The king allegedly constructed a city named "Tang" in Tu Fang's hinterland and suppressed its people. The state's origin is currently not determined, but there are already several suggestions. Hu Houxuan claimed that Tu Fang people were actually descendants of the Xia dynasty who survived the Xia's defeat at the Battle of Mingtiao.[60] However, the uncertainty of the Xia dynasty's existence makes the statement unfounded. Guo Moruo alternatively suggest that Tu Fang belong to the Xianyun, thus suggested that the tribe might have connections with Guifang. The claim itself, nevertheless, is still not certain.

In the eastern neighboring regions, the state of Dapeng (大彭) had been a vassal of the Shang dynasty since the early 14th century BC.[61] This was a notable autonomous region of the kingdom that lay in the eastern direction relative to Yin. According to traditional texts, the first ruler of Dapeng was given the title hou by Wu Ding's ancestors. The region was heavily influenced by Shang religion, because archaeologists have found in Dapeng's capital many sacrifices to the God of Earth, a deity that was also honored by the Shang. The country politically served as an autonomous state within the Shang territorial extent and a trading partner of the Shang core regions. During the previous kings' reign, the region is recorded to have maintained a relationship with Shang through rare tributes. However, during Wu Ding's period, Dapeng began to show hostilities towards the suzerainty held by the Shang king. In the forty-third year of his reign (c. 1200 BC), Wu Ding waged war on Dapeng and annexed the territory into the kingdom. Seven years later, his army went on to conquer Tunwei (豕韋).

Maintaining connections with Predynastic Zhou

During Wu Ding's reign, the far western regions (west of the western "fang" tribes) were inhabited by the Ji clan, predecessor of the Zhou dynasty. According to the traditional Chinese chronology, Wu Ding's royal family of "Zi" and the clan descended from the same ancestor, the Yellow Emperor. The tale implies that Predynastic Zhou was a member of the Huaxia civilization. The center of the chiefdom had been Bin (modern Xunyi County) for thousands of years, located very far from Wu Ding's seat in Yin. It was not fully brought under Shang suzerainty, but instead maintained a loose connection with the Shang kings. According to the Bamboo Annals, Predynastic Zhou had already been in contact with Shang, when Pan Geng appointed his minister Fen (邠侯, "Marquis of Fen") to monitor Zhou together with their leader Yayu (亚圉). Wu Ding's reign had considerably more inscriptions about Predynastic Zhou than later periods.[40] In one particular text (c. 1200 BC), the polity was referred to as Zhou Fang (周方), not Zhou; therefore, they were equated with other frontier polities. The name indicates that Zhou was seen by Wu's court as alien and adversarial. The Ji lords ruled over lands not actually belonged to Shang territory but were still granted the noble title Hou (marquis/marquess/lord). Other evidences of Shang-Proto Zhou relations are divinatory texts on Zhou soldiers' welfare, inquiries on Zhou hunts. On the other hand, Wu Ding never visit Zhou territory to tour or hunt. He also did not order Zhou manpower to aid Shang's public construction works and wars. Furthermore, despite his concerns about Zhou people's prosperity, he made no questions and divinations about whether their harvests were successful.

Predynastic Zhou did not actually participate in any expansion schemes of Wu Ding, and they also did not show discontent with the court (oracle bones dating back to Wu Ding do not show any signs of military conflicts between the chiefdom and his court[40]). Only after 1200 BC, the Ji leaders began to involve themselves more in their relationship with the last Shang kings. Perhaps their success in overthrowing Shang centuries later lies in their independence from the dynasty, which is shown from Wu Ding's reign onward.

Reassuring influence in the south

Chinese civilization developed in the Yellow River valley. Control of many Shang kings were often restricted to the regions surrounding the river and its tributaries. The other large river in China, the Yangtze (长江) was not usually the main place of Shang settlement. The plain instead was inhabited by several "fang" polities. Contemporary records primarily contain information of relations between the Shang kingdom and its northwest polities; inscriptions about southern peoples and their relationships are rare. Wu Ding's campaigns in the southern areas include his conflict with the Hufang (虎方), a Jingman tribe located between the Han River Basin and Huai River Basin.[62] During his reign, the general and official Wangcheng (望乘) was ordered to command a force to engage with Hufang. The army arrived at the Yangtze River's bank, in what is now between Suizhou and Jingshan (Hubei), and launched an offense via Gui (now Zigui County). The Hu Fang tribe, upon being attacked, surrendered to Wangcheng without much resistance. Subsequently, their land was merged into Shang's southern territory.

The people in the southern direction appeared to be much less resistant than those in other areas. For example, Wei Fang (危方), a chiefdom located between Henan and Anhui, was under Shang influence from the last kings before Wu Ding. According to the oracle bones, Wei Fang soon submitted to Shang when Wu just came to power. The majority of polities in the south cultivated good relationships with the dynasty; therefore, they were able to exist in stability as the Shang mainly concentrated on setting their dominance in the north and west directions. Many survived in exchange for recognition of Shang superiority in the Yangtze River plain. Oracle bone inscriptions rarely mention a southern polity that was hostile to Wu Ding. Due to the fact that southern opponents of him were few, he easily dominated the Yangtze River basin, expanding his rule further south than his predecessors had done. Several tribes submitted themselves under Shang rule and acted as supportive forces in its northwestern wars.

Roughly seventy-five percent of human sacrifices of Shang dynasty excavated at Yinxu date back to his reign. This shows his great military successes, since Shang human sacrifices consisted mostly of prisoners of war. Since Shang dynasty practiced slavery, the captured peoples that were not executed for sacrificial ceremonies were shown little mercy and forced to work for the king. For example, the Qiang slaves were expected to prepare oracle bones for diviners in coming ceremonies. [63]

Relationship with other ancient cultures

The Shang dynasty, despite being regarded by some historians having flourished in the "cradle of civilization" of China, was not the sole civilization in the country's current territory. Other signs of civilization also emerged in parts of Sichuan, located considerably distant from major Shang cities like Yin and Zhengzhou. Traditional histories say that the region was home to two states, Ba and Shu. Ba was an ancient confederation of tribes, and its history extended back to the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. The state had recorded relations with Wu Ding's kingdom around the 13th century BC, although the relation was mostly conflicts. The oracle bones documented on the division of Shang army attacking Ba.[64] The Shang forces, numbered up to thirteen thousand, were led by Xi Li Zhi and Hou Gao, under the commands of Fu Hao.[65] One of the battles with Ba was a large-scale ambush schemed by the Shang, the first one ever recorded in Chinese history.[65] However, Ba seemed to be unaffected by Wu Ding's influence, and it continued to be independent after his wars (the presence of Ba as an independent state during the Zhou dynasty proves that the state did not belong to the Shang).

The connection of Ba with Wu Ding might suggest possible relations with nearby cultures such as Sanxingdui, which is thought to be the site of the ancient kingdom Shu. There are oracle characters suggesting Shang's contact with a state named "Shu", it is uncertain whether the polity mentioned actually refers to the Shu that lay in Sichuan near Ba. The Sanxingdui archaeological site contains many artifacts of metallurgy; nonetheless, the items are evidently distinguished from those made by Shang dynasty bronze casters.[66] The differences suggest that there were no contact between Sanxingdui and Yin, and the bronzemaking techniques prevalent among Wu Ding's artisans did not influence the metallurgy of the Sanxingdui culture through peoples captured. Wu's military probably did not clash with the ancient settlement.

The eventual annihilation of northern states

Wu Ding's superiority in battles critically weakened the power of his opponents. Some tribes resumed their hostility after his death, though, but they were all destroyed in the last 100 years of the Shang dynasty. Some major polities that finally met their decisive defeats were:

- Guifang, identified with the tribe Guirong (鬼戎) during the reign of Wu Ding's great-grandson Wu Yi. In the 35th year of Wu Yi (possibly 1119 BC), Predynastic Zhou leader Jili attacked Guirong and defeated it.

- Dapeng, the eastern vassal. Sima Qian's work describes Dapeng's destruction by the marching army of Di Xin of Shang around 1060 BC, years after its re-submission to Wu Ding. The eventual annihilation of this state is thought to be likely a result of Di Xin's military expeditions along the Huai River.[67] About a hundred years after its fall, the Huaiyi confederation Xu rose in power and began to challenge the Zhou dynasty.

Significant events

The earliest version of Chinese writing, Oracle bone script (甲骨文; jiaguwen), found on tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae, was unearthed at the royal tombs in Yinxu. Wu Ding was the earliest monarch at that Shang capital. The contents are divinatory questions on war, human sacrifice, and national economy. The scripts are found to have almost all principles of modern Chinese writing, which suggests a previous period of development.[69]The basic modes of putting together characters are fully developed in oracle texts: pictographs (xiangxing 象形) or "pictures", ideographs (zhishi 指事) expressing an idea, combinations of two characters (huiyi 會意) forming a new one, combinations of shape and sound (xingsheng 形聲) expressing the field of meaning together with a pronunciation, and borrowing (jiajie 假借) a character for another one.[70] Another major type of Shang writing, bronze inscriptions ("jinwen" 金文), also came into use the same time as their bone counterpart. Shang bronze script was used in a smaller extent than oracle scripts, especially in Wu Ding's reign when only a few characters were cast on cerremonial vessels. They often contain information about family names and personal names of the individual being honored.[71]

Wu Ding's reign is the latest point at which chariots entered China.[51] They were acquired as a mature technology through interactions with nomadic tribes in Central Asia and the Northern Steppe (probably a branch of the then-Proto-Indo-European peoples),[72] and used for royal hunts and military command. Contemporary oracle bone inscriptions of the character 車 depict a chariot-like two wheeled vehicle with a single pole for the attachment of horses.[51] Many Shang chariots were eventually interred with royal family members in tombs. The Shang chariots, despite their limited utilization in tactical combats, remain prevalent throughout the Shang period and early Zhou era.

Astronomy in China traces its origin back to Wu Ding's time. Since the reign of the Shang king Tai Wu (太戊, around 1500 BC), there had been evidences of active astronomers serving as shamans, such as the family of Wuxian (巫咸) who held significant power in the court. Since the 13th century BC, numerous stars (that were later categorized) have been recorded on oracle bones at Anyang. The system of "xiu" (宿, lit."mansion") that played an important role in ancient astronomy also appeared during his reign.[73] The astronomy in this period laid the foundation for later scientists such as Gan De, Shi Shen and Zhang Heng. It is commonly thought that the earliest examples of Chiness mathematics also appeared along with astronomy, due to the strong connection between the two. The calendar, which served to organize days, appeared from the dawn of literacy. It arranges ten days into a week, a feature that was used by the royal house to schedule sacrifices. The evidences of using a recording method for dates in Wu Ding's reign later developed into a complete and complicated system. The days were organized into repetitive periods, each day's name containing two characters. The names of the days were frequently mentioned in Wu Ding's divinations, as they were believed to carry supernatural meanings. Later, its initial purpose was abandoned, but its importance in denoting dates continued for millenia. It was reinterpreted as a more abstract system of ordinals, one that could be creatively redeployed to label sequential or cyclical phenomena of many kinds in addition to days. Many of these new uses in their turn attracted a religious or magical focus.[74]

Bronze technology underwent a significant change starting from the late Shang era, whose beginning is taken from the reign of Wu. Quantity and quality of the products increased drastically. The most notable utilizations of them are war uses and tomb furnishings; the latter reflects a parallel between advancement in bronze weaponry and the sociopolitical development seen from Wu Ding's reign onward.[75] Large numbers of bronze weapons were excavated in tombs, suggesting the affluency and wealthy lives of the nobility. In terms of warfare, qualified bronzemaking settled differences between Wu Ding's armies and their rivals, which enabled him to extend both influence and land area. Along with the bronze products, the writing that was inscribed on them provides insights into the "artisan" class who made the bronze. Bronze scripts indicate that they enjoyed certain privileges, and had a defined occupation that was separated from the common people.

Women in government

At the time of Wu Ding's accession to the throne, women had a greater role to play in the exercise of official power than in subsequent Chinese culture. This is mainly due to the fact that the Shang was not influenced by Confucian ideologies which only appeared 700 years after Wu Ding (although its succession traditions preferred masculine children to feminine ones similar to Confucianism). The most prominent females in Shang dynasty were verified to have lived during his period. Most of them acquired power through marriage to the king. Wu Ding's spouses participated in warfare and divination, worshipping the Shang celestial ancestor Shangdi (上帝), along with participation in managing the kingdom's agricultural-based economy.[76]

Fu Hao, the queen consort, was recorded in oracle bones as a renowned military commander. Being skilled in warfare, she was trusted by her husband and was appointed a general. She held various campaigns against several groups in the west of Shang territory. At its peak, the forces of Fu Hao reached over 13,000 troops, headed by herself and subordinate generals. The force helped Shang dynasty conquer many opposing tribes and further expand their territory.

Although Fu Hao raised and commanded troops on behalf of Wu Ding, she did not have her own army or independent base of power like a vassal chieftain might.[77] Nevertheless, she was Wu Ding's favorite consort, being mentioned the most among the large number of his wives.

Along with warfare, it is known that the queen also played a religious role as a priestess. She was allowed to take part in ceremonies, sacrifices, and divination with Wu Ding's diviners. She featured herself in human sacrifices, as the humans killed were often prisoners taken from her post-war opponents. Some oracle bones contain graphics depicting her organizing executions of captured enemy for ancestor sacrifices.[78][79] As a priestess, she was one of very few women in Shang China who had full literacy. Many paragraphs on oracle bones happen to feature her as the diviner.[80]

As mentioned, Wu Ding spent a considerable amount of divinations on problems concerning his spouse. Most of them were about her pregnancy (see § Participation in Shang religious activities. The king took great interest in determining Fu Hao's child, and believed that the child's gender was affected by his/her birthday. He carried out a series of gender predictions that were based on the sexagenary calendar (that he divined collaboratively with the scribes):[40]

- Cracking the bones on the day yichou, Que (possibly a scribe) predicted: "the King's principal royal spouse Fu Hao shall give birth on the next gengyin day." The diviners then questioned on wuchen day: "When Fu Hao gives birth, shall it not be fortunate?" ("Fortunate" implied the conception of a male offspring).

- Cracking bones on dingyou day, Pin divined: "Fu Hao's conception is fortunate." Wu Ding otherwise prognosticated that if the child was born on a jia day then it would be misfortune. Later, Que predicted in jiashen day that Fu Hao was going to give birth. Wu Ding said that a birth on ding days and geng days would be greatly auspicious. However, it was recorded that 33 days later, she purportedly gave birth on the unlucky jia day: "it was a girl":[40].

Fu Hao's militaristic operations was dictated by divinatory inquiries, which decides her army's mobilization.[40] For example, a divination says: Cheng divined: "Fu Hao shall follow Guo of Zhi to attack the enemy. The King shall attack Zhonglu from the East to where Fu Hao shall be." Another text reads: "The King should not order Fu Hao to follow Guo, [because] we will not perhaps receive enough support."

Her health was perceived to be bad omens from evil influences, as a text says. The scribes also cracked a bone informing about Fu's sacrificial activities:[40] "We shall perform a yu-sacrifice to Father Yi (i.e. King Xiao Yi) on behalf of the Queen. The sacrifices will include a lamb, a decapitated boar, along with ten sets of sheep and pigs."