| Shang dynasty's state religion | |

|---|---|

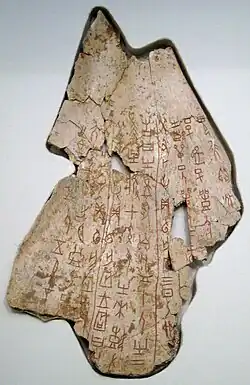

.jpg.webp) An ox scapula used by a scribe to record the outcome of divinations | |

| Theology | Polytheistic ancestor veneration Animism Shamanic practice |

| Region | China proper |

| Language | Old Chinese |

| Territory | Shang kingdom (with Yin as religious center) Influenced and vassal states |

| Origin | 2nd millennium BC Yellow River valley |

| Separated from | Prehistoric Chinese beliefs |

The state religious system practiced in China during the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 – 1046 BC) involved practitioners communicating with deified beings, including deceased (dynastic and pre-dynastic) ancestors and supernatural gods.[1] The primary methods of spiritual venerations were divinations, carried out on oracle bones, and sacrifices of living beings. The Shang dynasty also had large-scale constructions of tombs,[2] which reflects their belief in the afterlife. Numerous Shang vessels as well as oracle bones have been excavated in the kingdom's capital Yin.[3] The items collected provide extensive insights into the Shang's ancient beliefs, and the methods by which they were practiced.

The Shang religion covers many aspects of the dynasty, accounting for a large portion of court life. The deities worshipped by the practitioners received large-scale sacrifices, from animals, manual products such as bronze vessels, to human sacrifices. The Shang astronomers created a sophisticated calendar system based on astronomical observations.[4] Complying with the calendar, the diviners and sacrifice practitioners offered to almost every supernatural deities and deified ancestors in the pantheon. The Shang also schemed constructions of sacrificial temples, sacred places, and tombs for deceased royal family members. The religion's descriptive literary sources come from the oracle bone inscriptions that record divinations. The inscribers provided information about the gods concerned, the name of the diviners, the methods of sacrifices, as well as the purpose of honoring. Its system of beliefs also elevated the status of the royal family (especially the ruling monarchs), and concerned the roles of each type of people in the Shang court.[1]

The Shang religion originated in the Yellow River valley, heartland of the Huaxia civilization from 1600 to 1046 BC. The first documentary relics of this religion date back to the 13th century BC, during the reign of Wu Ding. Throughout over two centuries, the dynasty increased its cultural influence and experienced cultural exchanges by means of war. The Shang religion thus left several elements on surrounding polities. Around 1046 BC, the Shang dynasty reached its end and was replaced by the Zhou dynasty. The new regime gradually assimilated elements of Shang religion into its governing beliefs. The descendants of the Shang kings were ennobled by Zhou and governed several vassal states. The largest one, Song, continued to practice veneration of Shang dynastic ancestors and other gods.

Studies

This religion, having been one of the earliest established religious systems in China, was the state religion of the Shang dynasty. Many royal-governed cities across the kingdom practiced the religion, and its influence even reached Shang's vassals. However, only the last capital Yinxu and the city of Daxinzhuang (250 kilometers apart from Yinxu) contain written records of the practices[5]. When the Shang dynasty ended, both cities were abandoned, only to be rediscovered millennia later. When the oracle bones went under examinations in the 20th century, researches into the religious life of their producers began to attract attention.

As the Zhou dynasty practiced an essentially distinct religious system, and its interpretation of Shang beliefs was not founded, the artifacts and written documents of the Shang are the primary reliable sources of study. Even then, the true nature of many aspects in the religion is still a subject of debate among researchers. The Shang inscriptions only describe the powers of the spirits. The writings about the gods' mythological origin are not excavated anywhere, and the relationship of the gods with each other is not truly clarified by the divinatory texts. That makes it difficult to correctly study the ancient state religion. It is noteworthy that despite the obstacles, many insights into it have been done.

History

Development during the Shang dynasty

Before the dawn of civilization in China, the vast area of China proper was inhabited by various tribal confederations. Each of the tribes practiced its own system of beliefs. The religious beliefs in prehistoric China were based on ideas of animism, totemism and shamanism. Many ancient tribes in predynastic China shared a common belief in the spiritual world. The spirits were thought to possess divine powers. As such, they were able to intervene in and dictate the lives of the living realm's beings. That led to the necessity of direct communication with the spirits, through means of mystics. A group of specified individuals, known as shamans, arose and took responsibility for conducting their respective tribe's religious rituals. As religious leaders, the shamans carried out numerous aspects of tribal life. The ethnicities in the future heartland of Shang dynasty had practiced sacrifices and funerals.[6]

The Shang dynasty's religion inherited the characteristics of its predecessors. Its similarities with previous religions are obvious: its ideas were animistic and contained elements of shamanism. Its rituals of sacrifices and funerals bore resemblances with prehistoric beliefs. However, having appeared much later in the mid-2nd millennium BCE, the Shang religion was more established and sophisticated. Unlike the shamans who led many aspects of tribal religions, the Early Shang dynasty from the 15th century BCE onwards created bureaucratic positions. During the reign of Tai Wu, the astrologer Wuxian and his family occupied almost all religious positions in the king's court. Later, those officials were diversified and further specialized. The religion was also widespread: many Shang major cities apart from Yinxu, governed by royal relatives, practiced the same traditions. Another distinction is that the Shang religion possessed complicated perceptions. The religion did not have a sacred scripture. Instead, the oracle bone inscriptions served as means of practicing; they record daily rituals, gods and their powers, information about the pantheon's ancestral section, and the methods of conducting ceremonies.

During the late Shang period (1300 - 1046 BCE), the religion achieved its mature status. Many kings of the late Shang were deeply religious and actively involved themselves in those matters. Some monarchs made alterations to the tradition. The first notable change took place during Wu Ding's regnal era. This alteration was documented by the Zhou dynasty's Bamboo Annals, compiled centuries after its supposed time. According to the source, Wu Ding received an ominous omen when he was carrying out a sacrificial ceremony for his ancestor Tai Yi. His eldest son Zu Ji, the initial crown prince, used the opportunity to convince Wu in religious problems. After delivering examples and philosophical ideas, Zu Ji suggested Wu Ding reduce sacrifices to ancestors in number. From then, the amount of offerings was modified and decreased. Later, in the middle 12th century BCE, Wu Ding's youngest son Zu Jia reversed the reforms and critically increased the sacrifices.[7]

The Shang kingdom showed religious interactions with other cultures in China proper. In most cases, the religious influences of the Shang dynasty left an impact on its vassal states. For example, the Dapeng state practiced similar rituals and included a god in the Shang pantheon into their list of worshipped deities.

After Shang

In 1046 BCE, the Shang dynasty under the regime of Di Xin collapsed and was replaced by the victorious Zhou dynasty. This succeeding dynastic family used the practices of Shang religion to explain Di Xin's fall. The Book of Documents contains a chapter claiming that Di Xin discarded all the sacrificial traditions and therefore lost the blessings of his royal ancestors.

The Zhou dynasty, having been a vassal state of the Shang during its predynastic era, adopted elements of the Shang religion into its own beliefs. The kings of Zhou, throughout centuries, kept the tradition of honoring ancestors by offering sacrifices. The sacrifices only included animals and handmade artifacts, since the Zhou abolished the use of humans in ancestral offering. The Shang religion was still allowed to be practiced in the state of Song, which was a vassal ruled by the ennobled direct descendants of the Shang royal family. The Shang monarchs continued to be worshipped until the fall of Song in 286 BCE. The family of Confucius was traditionally regarded the descendants of the Shang kings, and therefore bestowed honorary titles by imperial dynasties. Kong An, a member of a branch of Confucius's descendants was enfranchised by the Eastern Han dynasty as the "Duke of Song" and 'Duke Who Continues and Honours the Yin'[lower-alpha 1] upon because he was part of the legacy of the Shang.[8][9]

The head of the Shang pantheon, Di, became assimilated and identified with Heaven of the Zhou dynasty. Later, when King Zheng of Qin created the title "Emperor" for himself[10], he combined Di with the character Huang (皇, "august") to obtain the term.

The sexagenary calendrical system devised by the Shang dynasty's astronomers later became the system of denoting dates used throughout Ancient and Imperial China. The sexagenary cycle is still in use in Mainland China for traditional festivals.

Practices

Divinatory texts

Divination was one of the most important aspects of the religious system, and it was widely carried out by the Late Shang monarchs. Oracle bones, which consists of ox scapulae, tortoise plastrons and carapaces, were the main materials for divinatory documents. At the last Shang capital city of Yinxu,[11]) approximately 150,000 pieces of bone have been unearthed, most of which contain divinatory communications with the Shang deities. The king and his court inquired about various topics, including warfare, agricultural successes and heavy harvests, personal well-being, weather and other related aspects. The practitioners held a belief that the eventual outcome of their actions were decided and dictated by the deities.[12] As such, numerous divination rituals were conducted to acquire the gods' acceptance of upcoming royal actions. The rituals were held by the king and his court scribes (多卜). Several deeply religious monarchs, such as Wu Ding, employed about 70 scribes to help him during the ceremonies.[13] Firstly, the writers inscribed inquiries on the bones. They then heated the bones and interpreted the bone cracks created by the heat. It was believed that the

pattern of the cracks represented the gods' responses for the inquiries.

The divinatory questions were written with the notation of the day during which it was inscribed. The Shang dynasty developed a complex calendrical system that was used for denoting and arranging days.[14] The ten Heavenly Stems and twelve early branches were used together as day names. Each questions and sentences begin with the announcement of the inscription date. The Shang calendar was also used in predicting future events. In many oracle bones, the kings and his scribes decided and prognosticated the future days that were thought to be "ill-omened" and "unanimous".[1]

Usually, the king was the person to come up with the final interpretation. The diviners were barely mentioned by name; some of them remained anonymous. The religion's divinatory tradition was highly well-arranged by name. The receivers of the questions were addressed by both their name and honorary title (for instance, "Grandfather" or "Ancestor"). In concerning numerical problems, such as the amount of sacrifices or the number of soldiers effective for successful battles, specific numbers were given in the questions.

Sacrifices

The Shang religion is a typical example of a sacrificial system. The sacrifices varied essentially, and the number of offerings attributed to a recipient depended his or her status. The materials for offering mainly came from three sources: handmade items, animals, and humans.

Manually made products

The sacrifices that were not living beings were mainly bones, jade, and bronzeware items. Some of the bone products were shaped into hairpins or arrowheads. The Tomb of Fu Hao contains over 560 such bone products. Jade was acquired through contact with other cultures in China proper, such as Longshan and Liangzhu.[15] The material was treated as precious, and sometimes the jade sacrifices were buried with their initial royal owners. Bronze came in plenty; the number increased during the Wu Ding period, which saw a major advancement in bronzemaking technologies.[16] The offering ceremonies involved bronze vessels with inscribed characters. If the sacrifices were intended to be accompanying the dead in their tombs, bronze weapons (like arrows and spears) together with decorative products could be added. At the last Shang capital Yin, thousands of bronze items have been unearthed, revealing the importance of this metal in Shang's procedure of honoring. There were also other minor materials that came in much smaller amounts. In particular, stones, ivory and even cowry shells were sacrificed.

Animals

Some species of animal served as offerings, both to the ancestral and supernatural sections of the religion's pantheon. Usually, canine species were killed to be consumed by the deified natural features.[1] Body dismemberment was the main method to consider when sacrificing dogs, while hounds were often simply killed.[1] The way the animals were offered did not seem to affect the expected actions of the deities: in fact, dogs were offered similarly in order to both maintain and end rains. Contrastingly, the Shang royal ancestors' attributed faunas consisted of various species that came from the state's animal husbandry. Sheep were intended for a wide range of individuals, spanning through generations (e.g. Shang Jia and Pan Geng were both recipients of sheep). Occasionally, domesticated goats and ox would be slaughtered and sacrificed on certain typical rituals. Elephants did not appear in daily sacrificial ceremonies, but instead are found in royal tombs[17](from those elephants, the Shang also obtained ivory).

Human offerings

The Shang dynasty practiced human sacrifice on large-scales. However, the source of humans served for this purpose was not the state's citizens. Instead, the court used the neighboring polities' people who had been previously captured in battles. Due to the Shang dynasty's superiority over its opponents in numerous aspects, it achieved victory a lot and obtained a large number of humans. A small percentage of these were spared to be slaves (most of them were expected to produce bronze artifacts). The rest were killed and their remains sacrificed to Shang ancestors. A single sacrifice alone could require hundreds of individuals killed, some numbered up to thousands. Regarding subjects for offering, the Shang did not distinguish the opponent's common people from their leaders, the latter were often reserved for high-honored ancestors (In oracle bone inscriptions, the neighboring polities' leaders were mentioned with lordly titles, indicating a certain level of Shang's politeness). The Shang showed their concerns about the numbers, as many divinatory questions from Yinxu show (The questions ask directly about the sufficient amount of men that could be offered). According to oracle texts, around the middle of the 12th century BC, Zu Jia altered the traditions and critically increased human sacrifices to his predecessors[18]. Human sacrifices to supernatural deities (except the supreme being Di) were subject to rules of offering. The men sacrificed had to be buried when the recipient was the earth deity, drowned when offered to water spirits, and dismembered when offered to wind spirits[19]. When Zhou conquered Shang in the 11th century BC, human sacrifice was abolished, although later some regions still practiced it at small levels.

The court employed officials to plan and carry out constructions of sacrificial places. Excavations at Yinxu revealed temple remains that came with palaces. According to oracle bone inscriptions, some of the buildings for rituals were the Royal Temple and the Temple of the Earth.[1] Other locations were natural, for example the Yue Mountain, the Yellow River bank and Huan River bank.[1]

Shamanic practices

Inscriptions on Shang oracle bones suggest a complicated religious system which concentrated on communicating with the spiritual world via ritual performance and the utilization of "numinous" media like bones and bronze. This type of communication, as some scholars point out,[1] can be interpreted as communication "without direct encounter". Other interpreters of Shang ritual bronzes, such as K.C. Chang, assert that this perception is not satisfactory, and that the Shang dynasty's religion must have borne considerable shamanic elements.[20] His view could be comprehended when examining remnants of Shang myths preserved by later dynasties, but Chang argued for the theory by studying animal patterns on Shang bronze. Animals were, according to his study, tools of the shamans: they served as intermediaries between human and spiritual realms, similar to other shamanic and totemic societies worldwide.

Chang's theory is resonant with modern understanding about the Shang religion, but it is also more or less speculative since available evidences do not allow the theory to be verified. Some other researches into whether Shang's religion was heavily dependent on shamanic beliefs employed the dynasty's written records as references. Studies of oracle bone scripts yield a character that corresponds with the later term "wu" (巫, commonly translated as "shaman"). The same terminology could be found in the state of Chu's religion. Additionally, the Shang written records mention several people whose names bore the character. Nevertheless, it is uncertain whether "wu" actually referred to shamans or to another kind of religious practitioners who used other types of practices to communicate with the spirits (Shamans achieve this goal by getting into altered states of consciousness). Victor Mair supported the view that the "shamanic" practices of the Shang dynasty resulted from earlier connections with other ethnicities.[21] He examined archaeological and linguistic evidences, and concluded that the word "wu" was etymologically and culturally related to the term "magus" (plural form "magi), a term used for priests in the Persian Zoroastrian religion. Specifically, Mair pointed out that linguistically, the word "wu" in Old Chinese had pronunciation similar to the word "myag", which is Old Persian for "magus"[22] This resemblance between the two languages suggests that initially, "wu" were non-Shang religious people, members of ancient Persian ethnicities that came into contact with the Shang kingdom through migrations into Central and Inner Asia. The term "magi" does not denote shamans; instead, it refers to priests that communicated with the spirits through the media of ritual and manipulative arts rather than trance and mediation.

R. Eno noted in his 2010 text: "Shamanism – if we allow some flexibility to the definition – was a widely dispersed religious form in traditional societies, and it is not unreasonable to anticipate that it was a feature of Shang religion, particularly since we have strong evidence for shamanism, denoted by the term 'wu', a millennium later in Chu religion. However, on the basis of current evidence, it is probably most accurate to say that claims for Shang shamanism, while not inconsistent with the evidence, are also not required by it, and that the theory remains speculative."

Practitioners

The Shang king was seen as the religious apex. Along with military and economy, he participated actively in rituals and other religious matters. Because the beliefs of the religion stated that the king's health and quality of life relied on the spirit world as well as the welfare of his kingdom, he involved himself in communication with the pantheon's gods. The king would try to assure that the spirits would give him guidance.[1] As in other religions found in other civilizations, the Shang king acted like a person connecting the human and deified realms. He was the head of the practitioners, directing and contributing in religious actions. It was the king who did all the divinations; the "diviners" whose names were recorded on oracle bones only acted like the "crackers" and "inscribers".

The Shang court had a developed bureau for carry out its religion. The group consisted of several positions, each was specialized in an aspect required in every religious matters. The officials include:[23]

- A group of diviners (duobu 多卜). They assisted the king in divination procedures. Each group was headed and supervised by a chief diviner (guanzhan 官占). They worked with the scribes (zuoce 作冊) and shamans (wu 巫)

- Record keepers (taishi ling 太史令): tasked with documenting the rituals.

- Astronomers (xi 羲, he 和) and astrologers (shi 史), tasked with determining days and months, both necessary for rituals.

- Shamans (wu 巫), whose work could vary. An example is Wuxian, a shaman under king Tai Wu in the 15th century BC.

- Dancers (wu 舞), and music directors (gu 瞽). Music was an important part of the offering process.

Supernatural beings

The supreme god "Di"

The Shang religion's pantheon consisted of many gods, which represented natural phenomena. The highest of the gods was Shangdi (上帝, "lord on high") or simply Di (帝).[1] The god was believed to be the supreme deity, exercising the greatest range of powers. His title was later made synonymous with the Zhou highest deity Tian: however, Di was the only high god revered by the dynastic Shang. In some oracle bone inscriptions, Di was described as a being who controlled natural forces as if controlling individual spirits in a hierarchy, which made him distinguished from the other worshipped gods.[1]

The list below presents the known powers of the high god Di. His abilities were described on oracle bones not so directly but through pairs of affirmative and negative statements.[1]

1. Di controlled and decided the weather: the Shang kingdom's economy was based on agriculture, which relied heavily on the weather and climatic patterns. The Shang people believed that the weather was controlled under the power of Di, and they wrote a lot on predictions about his decisions. The weather patterns subject to Di included:

- Rain: "Di will order sufficient rain that makes our harvest successful."/"Di shall not send sufficient rain that makes our harvest successful.". Another prediction records: "From today to the day gengyin Di will send rain."

- Wind: "On the next guimao day, [perhaps] Di shall order wind."

- Cloud and cloud dispersal: "[Perhaps], when the thirteenth month in the year started, Di will clear out the clouds" (A Shang year might include a thirteenth month).

- Drought: "Di shall [perhaps] send drought upon our land"/"Di shall not send drought upon our land.".

2. Di gave military supports and other related assistances: "When our army attacks the Qiang Fang, Di will probably support us.", "When the King travels to survey the fang territories, Di shall support him.", "It does not rain, [maybe] Di doesn't support us.".

3. Di provided food and support harvests:

- "We ought to call out, Di will supply us food and provide support"

- "Di will or will not harm our harvest". One bone reads: "The King prognosticates that Di will not harm our harvest."

4. Di had the authority to approve the human's everyday decisions and actions:

- "Di will probably approve of the King's upcoming establishment of a town."

- "The King will not follow Guo, and Di approves."/"Guo shall call upon the King, and Di approves.". "The King" here refers to Wu Ding, who carried out numerous military campaigns. "Guo" was Guo of Zhi, a regional lord who commanded a border army and provided assistance for Wu Ding.[24]

- "This rain is very unusual; Di does not approve of this city and wants to destroy it."

5. Di could send disasters: The religion's practitioners believed that although Di aided them in various aspects, he could also harm them by his powers

- "The fang has attacked and destroyed our regions; it is that Di has ordered disaster to be inflicted upon us"

- "Divined: if we make a proper sacrifice, Di will not send down disaster. Tenth month."

- "Rain poured. Di has sent down devastating disaster upon this city."

- "The King will perhaps suffer from Di's disaster."

There were several other powers that Di was perceived to possess; the oracle bones mention them in the form of above sentences. The Shang paid great attention to the deity's decision of weather, and many oracle bone texts recording the climatic patterns also link them to other auspicious (or bad-omened) events.[24]

Natural deities

The natural deified beings in Shang pantheon were inscribed on oracle bones as subordinate spirits of Di. Some were often sent by Di and received their own honors by humans. Some others were geographical features of the region.[24] The list below gives some examples of the deities. The diviners wrote their own names on the sentences; some of the names are Ji, Que, Bin, Zhong, Pin.

1. Climatic phenomena and astronomical bodies

- The Sun: the Sun was treated as a god and received sacrifices. It was also sometimes interpreted as a "guest", that is, it was sent by Di to the Shang king. One bone inscription has the following sentences: "Crack-making on wuxu day: call within for Que to sacrifice sheep and goats to the [rising and setting] sun.", "Crack-making on bingzi day, Ji divined that the King will receive the Sun as guest, and sacrifice will be without fault.", "On xinyou day and guiyou day, we shall offer sacrifices to the rising sun."

- Clouds were believed to be sent by Di and also treated as deities. A divination records that Que was called to do a sacrifice to Di's clouds, the sacrifices being two hounds.[24]

- Winds: four separated divinations indicate that the main subjects for wind-sacrifice were dogs and hounds.[24] The dogs were offered to the winds through means of dismemberment. However, it is uncertain whether the sacrifices were actually for the winds or to other spiritual beings who controlled them.

- Rain: Dog dismemberment was the main sacrificial method. The divinations for rains, unlike those for winds, specify the place of sacrifice: one ritual was done at Yue Peak, another at the "Altar of the Earth".

- Snow: "Perform a sacrifice to Snow; there shall be a great rain."

2. Natural features of the landscape: The Yellow River was a feature that was deified. Commonly called in ancient times He (河, literally "the River"), this exceptionally long river affected the agriculture greatly. Other rivers along with mountains were also revered.

Bin (a diviner) wrote: "Crack-making on xinyou day, divined: We shall pray for a good harvest to (at the) River." Another inscription describes "perform a rain-dance to (at the) River". The Huan River had a divination saying: "Will the Huan River bring disaster to this city?" ("disaster" here might mean the river's flooding). One mountain honored was the Yue Mountain. Many historians believe that the mountain was actually Mt. Song, a tall mountain lying near the Yellow River.[24] The diviner Pin wrote on wuwu day: "By a sacrifice, pray for harvest at Yue Mountain." The previously mentioned rain-dance at the Yellow River was also ordered to be carried out on this mountain.

The High God Di's identity

There were many deities and gods in the Shang pantheon. However, it was only Di that was described in detail and thus the most studied god. This system of structured spirits featured Di as the apex, hence making him corresponding with the "leading" role of Zeus in Ancient Greece and Tian in Zhou dynasty.[24] The approaches of conceiving Di as the apex of Shang pantheon vary and do not agree with each other. There are three reasonable approaches, each of which can solve certain problems in the oracle bones, but they also contain their own questionable points.

Explanation 1: Di's identity deified the kingship. The first suggestion links Di with the existence of the High Ancestor Ku, who was mentioned in Sima Qian's Shiji as the Shang dynasty's ancestor.[24] Ku was addressed "High Ancestor" in more than four oracle bone inscriptions. Many prominent scholars support the view that Di and Ku actually represent an identical power. Its implications for the current understanding of the religion's theology are additionally profound. Some historians assert that if the Shang system of gods featured the highest and supreme deity as a primal ancestor of the rulers, then the monarchs themselves would be acceptedly seen as possessing divine powers. In other words, the kings would be perceived as embodying the power of Di (or Ku), being the "thearchs" by birth.[25]

Explanation 2: Di's identity conveyed the Shang's perception of the universe. Another reason for the identification of the two figures is that it strengthens the cohesion of the Shang pantheon and explains systematically the connections of the natural and ancestral sections. But it also has inconsistencies. For example, the names Di and Kui (identified with Ku by modern historians) were used differently from each other. In oracle texts, Di issued orders to other subordinate beings, while Kui did not. Sending down approvals was the responsibility of Di, not Kui. Furthermore, the way Kui is described in oracle bones suggests that the figure lay in an "equal" relationship with other beings", which challenges the possibility of him being the pantheon's apex. Nevertheless, this approach is still attractive among scholars who seek to find Di's identity.

The second approach relates the means of astronomy to Di. David Pankenier proposes that Di was likely to be a representation of an astronomical aspect of the Shang dynasty.[24] Pankenier argues that the religion of Shang was partly based on an interest for patterns in the night sky, and that this interest traced back to periods preceding the dynasty. Apparently, the constructions schemed by the Shang aligned with the position of the star at the north pole, which Pankenier believes that had been gradually displaced by another star. Such accuracy in observation despite changes indicates a highly complex comprehension of astronomical bodies. Therefore; it could be the fact that the position of the true north pole was of crucial importance to the religion.[24]

David Pankenier points out a possible reflection in the oracle bone character for "Di". He claims that it can be projected on the north polar region of the ancient sky in the time of the Shang in such a way that its extreme points correspond with significant visible stars, while the intersection of linear axes at the center will map to the vacant Celestial Pole.

_n.1.svg.png.webp)

_n.2.svg.png.webp)

It is possible that Di was perceived as a deity dwelling around the pole; this notion was popular among the dynasties after the Shang, and it seemingly ties Shang religious beliefs to the ones attested in the Classical Texts. By comparing the similarity of two religious practices that are known to be separated by centuries, Pankenier suggests that the oracle bones may contain unobservable "subtexts" containing information on astronomical findings.

The last point also poses a challenge to this theory. No evidence on oracle bones illustrate such subtexts. The astronomical observations required were barely mentioned by oracle bones, which means that Pankenier's theory is "speculative". Its reasonability is logical but it lacks sufficient evidence to be verified.

Explanation 3: "Di" was used as a generalized term. The third view on the existence of a specific Di argues for the opposite, that the religion did not possess a "High God" in its pantheon.[1] It asserts that Di was generic, and that the perception of Di being a single deity is affected by a projection of word usage onto the oracle scripts: that some read of Di using the post-Zhou conquest terminology, which associates Di with Tian.

There are debates among scholars about whether Di belonged to the supernatural section of the Shang worshipped spirits. Some claim that Di could not be a part of Shang ancestors, no matter how distant. Robert Eno pointed out oracle bone inscriptions that support the view.[1] The oracle bones state that Di could destroy (and one say that Di would destroy) the Shang capital. He claimed that this destructive action could not be done by royal ancestors, reliant on sustenance by receiving sacrifices which were mostly conducted in the capital. This leads to the view that Di was not likely to be perceived as a member of the royalty. But it contradicts with the fact that the character "Di" was also used to refer to deceased kings (although the use was limited). Eno argued that if Di actually referred to a High God, then addressing dead monarchs with the title would elevate them onto the level of gods, which he considered unlikely when interpreting the powers of the ancestors.

There is another fact that Di received no sacrifices as other deities in the pantheon. It indicates that Di had to be a distinguished deity who was unaffected by any demands for human's offerings like other gods, treating humans and spirits in the same way. One suggestion of this places Di on a level of "super-god" with powers surpassing that of common spirits. But this is not compatible with the fact stated above that Di was used to call dead kings who were obviously different from gods. Furthermore, the ancestors addressed "Di" also received sacrifices. R. Eno proposed another suggestion: "Di" was generic, referring to no specific god but to all the spirits. This explains why the term was used by the Shang to denote some kingly ancestors.

Deification and veneration of deceased people

Posthumous naming traditions

Aside from the supernatural beings, the ancestors of the Shang kings were also revered. The recipients of honors included both dynastic and predynastic ancestral individuals. The kings of the Shang dynasty were given posthumous names (names conferred after a king's death). The Shang religion used a well-structured system of naming kings, which relied on the calendrical convention. According to the dynasty's calendar (appeared around 1300 BC), a year was divided into 36 or 37 xun (旬, literally "week"), each lasting 10 days. The 10 days in turn were named after the 10 Heavenly Stems;[27] the common arrangement starts with jia (甲), followed by yi (乙), bing (丙), ding (丁), wu (戊), ji (己), geng (庚), xin (辛), ren (壬), ending with gui (癸) as the weekend. The Shang naming tradition did not follow a mere line parallel with the set of ten days; in fact, there were several religious rules that dictate the naming decision:

- The Heavenly Stem used as one's title had to be the first day of his reign (in the Shang calendar). For example, Wu Ding got his posthumous name from the dingsi day in which he accessed the throne.

- Every Shang king was prohibited from having gui as his posthumous name.[28] This is interpreted as a taboo, most probably because the use of gui would make one's posthumous name identical with the last predynastic Shang ancestor Zhu Gui (主癸). The prohibition can be obviously seen in the genealogy of Shang kings given by the oracle bones, in which every king used all stems except this gui.

- Successive kings had to be named after different Heavenly Stems. If a king was named with a gan (stem), the next king could not use the gan. However, a father and a son in non-successive reigns might have the same gan.[29]

- Alternative posthumous name: in some cases, the first day of the accession year would dictate the gan of the previous ruler's posthumous name. In such situations, the name would be named after the first day of the year after the 3-year filial mourning.[30] David Nivison, in supporting this, provided an example of Zu Geng, who used geng, the first day of Shang calendar 1185 BC, three years after he started reigning-mourning for his father Wu Ding. In another specific case, the first day of the initial regnal year was gui. The name was named after the day after gui, that was, jia. The resolution of the taboo name was seen in kings such as Zu Jia.

The Shang full royal genealogy includes around 30 kings, so the dictating rules did not prevent the repeated use of a stem as name. However, for distinguishing different kings, a set of prefixes was used, each of the prefix carried a specific meaning. Often, the prefixes such as da (great) or tai (also means "great") were used in names for:

- The first kings who got a stem as name. For example, Tai Geng, Tai Wu, and Tai Jia were the first kings who bore their respective stem name.

- The kings who contributed significantly to the Shang dynasty. A notable example is Tang, whose posthumous name given by the Shang worshippers was Da Yi and Tai Yi. He is now known in traditional Chinese history as the virtuous founder of the Shang kingdom.

Nivison, after studying the Bamboo Annals, suggested that Zu Jia was the first Shang king to immediately confer posthumous names for his chosen immediate heir while he was still reigning. He asserted that Zu Jia's action aimed to prevent the threat of throne usurpations, by granting official titles on his expected successor in advance.

It was also a convention of the Shang dynasty to apply the same posthumous naming to female ancestors. The royal consorts of the Shang kings were given Heavenly Stems as name, although the naming in this case did not follow the religious limitations as for the kings. In particular, the restraint from the use of gui did not affect the consort's posthumous names: one of Zu Ding's queens were posthumously titled "Yan Gui" (妣癸)[31]. The criteria for choosing a consort's Heavenly Stem are unknown.

Sacrificial rituals

The same as posthumous naming, the Shang performed sacrifices to ancestors with patterns complying with the calendar. In every day in a xun (week), a deceased ancestor would be chosen to be the recipient of specific sacrifices. On the gui day, the weekend, the reigning king and his assistants specialized in rituals would make a typical inscription that announced the sacrifices for the next day.[32] A year was sectioned into three periods, the first of which usually lasted 13 xun.[33] The first third was to perform ji, zai and xie sacrifices, the second for yong sacrifice, and the last for yi sacrifice. At the beginning of each third, a common ceremony honoring all the targeted recipients (gong dian) was held.[34] There are debates on determining the starting type of ritual among ji, zai and xie, which some taking ji as the possible choice.[35]

David Nivison constructed a partial schedule of ancestral sacrifices using information from oracle bones. He stated that to obtain an accurate schedule, the oracle bones must contain texts that are long enough.[36] He gave a particular example of an inscription describing the daily progress of King Di Xin's campaigns against the opposing chiefdom Renfang. He found out that the launching of the campaign coincided with the zai sacrificial day to the predynastic ancestor Shang Jia, and that the ritual cycle began with the gong dian day of 9th September 1077 BCE.[37] He further reconstructed a particular schedule of sacrifices to all kings whose posthumous name included jia.

The sacrificial rituals were held based on the belief that the deceased ancestors possessed the ability to intervene in affairs and events of the state. They were viewed as divine powers who could affect war outcomes, hunt successes, childbirth, and even the reigning king's health. The sacrificial materials varied greatly, and they were offered in high amounts in order to appease the ancestors: apparently, the ancestors who had died were thought to be able to do harm to the living realm just like Di.[1] By the time of the Late Shang period (1250 - 1046 BCE), scheduled sacrifices dominated the life of the court at Yin. The Late Shang had developed a sophisticated offering process, with each major ancestor receiving five grand ceremonies divided into smaller rituals of sacrifice. The Shang court performed sacrifices daily; therefore, a Shang year became synonymous with a ritual cycle. For example, the phrase "third sacrifice" would mean "year number three".

Every sacrifice, a group of scribes were tasked with recording the procedures. They often inscribed a sentence conveying important aspects of a typical sacrifice. An inscription about sacrifices would include the day of performance, the name and title of the recipient and the sacrifices in terms of material and number. Sometimes, the texts would contain the name of the inscriber/diviner and the place in which that sacrifice was carried out, and in specific cases the wishes wanted to be turned real by the recipients.[1]

The ancestors' power

The Chinese have long believed in the deceased ancestors' divine abilities. This thought is reflected the first time in the Shang religion, which concentrated significantly on the ancestors' impact of the living beings. The Shang dynasty's inscribers wrote a great deal of ancestral names on oracle bones. Every time a king passed away, his posthumous name would be added to the list of royal ancestors and to the schedule of offerings. Many of the Shang kings' names found on oracle bones attest to the genealogy given by Sima Qian's Shiji, and the names of predynastic clan leaders have also been found. The earliest Shang ancestor to be included in sacrificial ceremonies is Shang Jia (上甲). According to classical Chinese traditions, Shang Jia was the leader of the Shang tribe, surnamed Zi (子), six generations before the official establishment of the Shang dynasty. The list of predynastic Shang rulers goes as: Shang Jia (generation 1), Bao Yi (報乙), Bao Bing (報丙), Bao Ding (報丁), Zhu Ren (主壬), Zhu Gui (主癸). Their names all comply with the Shang calendrical rules. The royal line with kingly sovereignty started from Zhu Gui's son Da Yi (Cheng Tang) and progressed to the last king Di Xin.

The deceased kings, unlike the divinely supernatural gods in Shang religion's pantheon, were often involved in personal issues of royal members. The nearest previous generation of the reigning monarch was the one whose members were held responsible for the monarch's well-being. Several kings like Wu Ding were highly religious, and had serious beliefs that their health depended heavily on the mood of ancestors. Particularly, Wu Ding was an admirer of his kingly uncle Pan Geng, the first king of the Shang's Yinxu phase. Having reconstructed oracle

bone records of a divinatory ceremony which took place during Wu Ding's regnal period, David Keightley stated that the rituals were held in order to convince Pan Geng to improve Wu Ding's dental health.[1] The interpretation of the oracle bones shows that Wu was in awe of his predecessors' powers, and that the toothache he was experiencing had to be caused by some ancestral agencies. Pan Geng was offered two animals and asked for the nephew's teeth treatment.

Such sacrifices in exchange for the ancestors' exercise of power in the living realm was not uncommon among the Shang practitioners. Sacrifices came in large numbers, since the kings thought that high numbers of offerings would be satisfactory and sufficient to appease the dead royal relatives. An full sentence written on oracle bone reads: "Crack-making on bingwu day, Xing asked that whether if on the next dingwei day we make yi-sacrifice to Father Ding there will be no misfortune." That linked the recipient's contentment or discontentment to the possibility of disasters. Another sentence indicates that the choice of recipients during a sacrifice also affects the probability of a misfortune happening in the near future: "Crack-making on dingmao day, Yin asked that whether if the King chooses to receive Da Ding as guest [i.e. recipient] in the xie-sacrifice there will be no misfortune." The predynastic Shang leaders also had power on another aspects such as agricultural successes. The earlier the time frame of the ancestors, the greater their impact on the state. Shang Jia and his subsequent five predynastic leaders were addressed the "Six Spirits", and were thought to be the beings who dictated harvests. For instance, Shang Jia was often requested good harvests (indirectly through intermediary spirits) in exchange for a deal of animals.[1]

An obvious feature that make the Shang religion somewhat distinct from later beliefs is that the female ancestors were also revered along with their male counterparts. The oracle bone inscriptions mention some of the most important female Shang ancestors, who were grand royal consorts of the kings. Apparently, the Shang dynasty was when living women were given more opportunities to participate in governmental affairs. After their passing away, they were also granted posthumous titles in accordance with the ten gan. The inquiries of the diviners to female deceased individuals illustrate the beliefs in their role in later life. They were perceived as being unfriendly and angry on some occasions, and after such divinations they received offerings. Some females who were mentioned in oracle bone divinations are:[1]

- [...] Ji: "We shall protect the King's eyes against Grandmother Ji."

- [...] Geng: "The King's son met with disaster on account of Mother Geng."

- [...] Bing: "We shall perhaps pray to High Grandmother Bing for the conception of a child."

Burial traditions

The Shang dynasty's architects schemed and supervised the construction of burial tombs. The tombs' remains now come in large numbers, which illustrates the dynasty's strong belief in the afterlife. The tombs were not solely reserved for kings: queen consorts, royal concubines and the rulers' offspring (some of them did not become kings) had their own places to be interred. The Shang developed a complex viewpoint of tomb building, and the layout of their works was dictated by the status of the person buried. The largest place for the "afterlife" lay in the Royal Cemetery, located in what is now Xibeigang (西北岡), Anyang. The site, belonged to the ancient capital city of Yin, served as the resting place for almost all royal family members. Lay within the cemetery are many tombs, each of which contains numerous Shang artifacts. The artifacts in every tomb (bone, jade, bronze,...) are different, indicating a distinction between the royal status of the person interred. Several tombs also served for the purpose of rites, mostly as honorary temples where scheduled offerings were conducted.

Using radiocarbon dating and other techniques, researchers have constructed a list of genealogy of the individuals buried. The following data are from the study reports of Koji Mizoguchi and Junko Uchida, published in 2018.[38]

The two authors constructed a list of tombs built from the reign of Pan Geng to Di Xin, corresponding to the Shang dynasty's Yinxu period. The list goes in tomb assigned numbers: M1443, 50WGM1, M1001, M1550, M1400, M1004, M1003, M1002, M1500, M1217, M1576. Their research reveals a fact that the artifacts found in tombs of individuals with superior-inferior relationships differ from each other in many characteristics, which illustrates the tradition of distinguishing royal status among the family.

What most indicates the veneration of older peoples (predecessors) is that the planners of the cemetery based their construction works on a belief that respect had to be paid by all ritual conductors, regardless of which funeral or sacrificial ceremonies they were in. This pattern is seen obviously from the tombs of Wu Ding and his nearest generations. Wu Ding's uncles Xiao Xin, Pan Geng were buried in tombs 1443 and 50WGM1, and his father Xiao Yi's tomb is 1001. Wu Ding's own place of burial (1400) and that of his oldest child Zu Ji (1550) were built naturally so that the mourners of them had to pay additional respect to the three previous kings. Obviously, the ideas of the Shang religion suggested that respect was as necessary as mere sacrifices to appease the deceased. Zu Ji died during Wu Ding reign, and it was proved that Wu Ding was the one responsible for building their burial pit. Since Wu is somewhat superstitious and an admirer of his previous generation, it is not surprising to find out that he intended to place the two tombs in that "respectful" position. Again, 1550 was placed in a similar manner, as Zu Ji was Wu's son and initial successor.

Concerning the tombs of Zu Geng (1004) and that of his grandfather Xiao Yi (1001), the authors interpreted that a successor was not religiously restricted from having lower royal status than his predecessor. The two tombs were built to display the genealogical closeness of the two persons. On the other hand, the northwestern location of 1004 compared to 1001 indicates that Zu Geng's status was higher than his grandfather, and the mourners of the latter were intended to respect the former. The builders of 1004 also positioned it in a pairing location with Wu Ding's grave, intending to create an "equal" relationship.

The three tombs 1550, 1004 and 1003 aligned with the respective age of the three brothers Zu Ji, Z Geng and Zu Jia. This is inferred from the features found on each tomb's artifacts. The reconstructed genealogy of tombs identifies Tomb 1550 at Xibeigang as the tomb for Zu Ji; the tomb's dating matches the alleged time frame for the former crown prince's death. Two other tombs, 1004 and 1003, were respectively built for Zu Geng and Zu Jia. The spatula paintings of Tomb 1004, specifically, are absent in terms of large size, and those with smaller sizes are less sophisticated and flatter in execution than Tomb 1550 (other items date exactly to the time of Zu Geng's death). This indicates 1004 was built after 1550. The same pattern applies to 1003, where the spatulas were found to be even more simplified. The constructed time of tombs based on dating is therefore 1550, 1004, 1003. It matches perfectly with the genealogy found in oracle bones. Zu Jia's grave, unsurprisingly, was located strategically so that it indicated his status as the successor of the 1004's deceased, who was Zu Geng.

The last king of Shang, Di Xin, committed suicide after being defeated by his vassal Zhou. The fact that he was not buried in accordance with Shang's tradition was due to his immoral and impious images made up by the Zhou dynasty.[39]

Effect on royalty

Religious effect on the throne

It is reasonable to say that the Shang dynasty's complex religious system had important effects on the royal family, especially the perception of kingship. Evidences, both from archaeological and documentary sources, show that the kings played essential roles in the state's administration. Notably, the aspect in which the kings were the most active in was religion. In fact, it seems that the Shang king's power derived itself partly from his religious roles. Scholars have studied Kui, a mysterious deity in the Shang pantheon that has been poorly comprehended[40]. They presented a theory suggesting that the worship of Kui was the result of incorporating other beliefs. The Shang dynasty is known for its mostly-victorious campaigns targeted at adversarial neighboring polities. As the polities themselves gradually submitted under the kingdom's sovereignty, their gods became assimilated into Shang culture. Some tribal ancestors and deities were "adopted" by Shang religion and treated equally with the dynasty's original spirits.

This indicates that the King functioned as the state's head priest. Therefore, his role was equal to that of a religious center, keeping the surrendered tribes and chiefdoms under his sovereign power by mediating among the spirits of both the submitted and his own. The nature of kingship was also derived from the deified beings. The power of Shang royal ancestors did not remain the same through generations. The nearest generations of the reigning king-parents, uncles, grandparents-were perceived by his court as having limited power, exercising their divine abilities just on the royal family alone. In contrast, the most distant ancestors such as Shang Jia (and generally the Six Spirits) had great influences over important national affairs, which means that their ability rivaled that of the most powerful gods in the Shang pantheon. In other words, they were universal deities. This means that the Shang kings could be considered "living deities on earth".

Members of the royal clan were devoted practitioners, since they were also dependent on the deities' power. The religion was practiced across the state, as many royal members were given a portion of the kingdom's land to govern. At Yinxu, almost all family members' role in religious events were mentioned in oracle texts.

Favor of masculine gender

The system furthermore affected the continuation of kingship. The Shang tradition allowed female individuals to participate in government; however, it was overall a patriarchal society. In fact, the influences of male ancestors overwhelmed that of their feminine counterparts in scale. The person responsible for functioning as head of the clan and head of the religious practices had to be a male. Apparently, a male would carry the ancestral surname "Zi" and pass it to subsequent generations, while a female could not. Therefore, the throne had to be occupied by males only. This can be seen in many Shang generations: many of the kings had documented daughters who never became monarchs. It seems that the tradition of sibling-sibling succession that the Shang used for the most of its dynastic course only applied exclusively for the masculine gender.

The conception of male children was considered a serious matter by the Shang dynasty, as they expensed a considerable of divinations on this aspect. Again, it seems that the ancestors played a role in deciding the children's gender. However, the oracle bones show that the Shang considered another factor contributing to this, that is, the birthday. The conception of Fu Hao, Wu Ding's second primary consort, was of interest to his court. The king together with his assistants carried out numerous birth divinations all predicting the baby's birthday[41]. The results gave out days of misfortune and fortune. Wu Ding divined that if his wife gave birth on the days with the stem jia the child would be a girl. On the dingday, the gender would be the opposite. The oracle bone inscriptions record that Fu Hao gave birth on the unfortunate day of jiayin, 33 days after the prognostication.

Addressing one's ancestors

Although the dead royal members received posthumous names, the oracle bones often do not refer to them by their full title. Usually, only the Heavenly Stem component was used, combined with another preceding character which defines kinship. The prefix indicates the addressed subject's familial relationship with the reigning ruler, and often with a much broader sense than their modern meanings[42]. The Shang developed a system of prefixes used directly in ceremonial practices; the words used indicated the practitioners' veneration and admiration of their ancestors:

- Relatives who were 2 or more generations before the incumbent ruler would be referred to as zu (祖) (for males) and bi (妣) (for females). In this context, zu means (great) grandfather, patrilineal great uncle; bi means grandmother and other consorts of zu. Sometimes, "zu" could be used officially as the posthumous name's first component.

- The previous generation: fu (父) was used for male and mu (母) for female. Again, the masculine indicator means the father or paternal uncles, and its feminine counterpart denotes the mother or the father's other wives.

- The same generation: only the character for males has been found, which is xiong (兄, "older brother"). This word could also be applied to paternal cousins.

- The next generation: the king's sons and nephews were referred to as zi (子). The word is sometimes understood as the surname of the Shang rulers, but this is not confirmed. Often, the "zi" came with the given name of the person, which makes it acting like a surname. However, the first kings of the Shang dynasty reigned when no excavated examples of writing was present, so it is impossible to determine their surname. Some argue that "Zi" was used only for denoting a Prince.

As the prefixes were used based on the relative kinship, the word for a relative changes over generations. For example, Fu Jing was referred to as "mu" during the reign of her son Zu Jia (the "mu" appeared on the Houmuwu ding, a bronze vessel that Zu Jia commissioned in honor of his mother). To the reign of Zu Geng's nephews Lin Xin and Geng Ding, she was called "Biwu" instead of "Muwu".

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Eno (2010a).

- ↑ Mizoguchi; Uchida (31 May 2018). "The Anyang Xibeigang Shang royal tombs revisited: a social archaeological approach".

- ↑ Bai Shouyi (白壽彝), ed. (2002). An Outline History of China. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 7-119-02347-0.

- ↑ Smith, Adam Daniel (2011). "The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Origins of the Calendar". In Steele, John M. (ed.). Calendars and Years II: Astronomy and time in the ancient and medieval world. Oxbow Books. pp. 1–37. doi:10.7916/D8891CDX. ISBN 978-1-84217-987-1.

- ↑ Smith, Adam (2010). The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Foundations of the Calendar.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Nickel, Lukas (October 2011). The Prehistory of Religion in China. Oxford University Press, p.443. ISBN 9780199232444.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Felipe Fernandez-Armesto. The World: A History, (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: 2007), p 84.

- ↑ Rafe de Crespigny (28 December 2006). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). BRILL. pp. 389–. ISBN 978-90-474-1184-0.

- ↑ 《汉书·杨胡朱梅云传》:初,武帝时,始封周后姬嘉为周子南君,至元帝时,尊周子南君为周承休侯,位次诸侯王。使诸大夫博士求殷后,分散为十余姓,郡国往往得其大家,推求子孙,绝不能纪。时,匡衡议,以为"王者存二王后,所以尊其先王而通三统也。其犯诛绝之罪者绝,而更封他亲为始封君,上承其王者之始祖。《春秋》之义,诸侯不能守其社稷者绝。今宋国已不守其统而失国矣,则宜更立殷后为始封君,而上承汤统,非当继宋之绝侯也,宜明得殷后而已。今之故宋,推求其嫡,久远不可得;虽得其嫡,嫡之先已绝,不当得立。《礼记》孔子曰:'丘,殷人也。'先师所共传,宜以孔子世为汤后。"上以其语不经,遂见寝。

- ↑ Wilkinson, Endymion. Chinese History: A Manual, pp. 108 ff Archived 25 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Harvard University Press (Cambridge), 2000. ISBN 0-674-00247-4. Accessed 26 December 2013.

- ↑ Keightley (1999).

- ↑ Keightley (2004).

- ↑ Theobald, Ulrich (2018). "Shang Period Government, Administration, Law".

- ↑ Steele, John M. (2010). The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Origins of the Calendar. doi:10.7916/D8891CDX. ISBN 978-7-5027-0532-9.

- ↑ Buckley Ebrey, Patricia. "Jade from Fu Hao's Tomb". A Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization. University of Washington. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- ↑ Chen, Fangmei. The bronze weapons of the late Shang period. ProQuest LLC (2018).

- ↑ Theobald, Ulrich (2018). "Shang Period Economy".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Felipe Fernandez-Armesto. The World: A History, (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: 2007), p 84.

- ↑ Ruth H. Chang (September 2000). UNDERSTANDING DI AND TIAN: DEITY AND HEAVEN FROM SHANG TO TANG DYNASTIES (PDF). SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS (Number 108).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ K.C. Chang (1983). Art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Authority in Ancient China.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mair, Victor. Old Sinitic Myag, Old Persian Magus, and English ‘Magician’”(Early China 15, 27-47).

- ↑ Mair, Victor. Old Sinitic Myag, Old Persian Magus, and English ‘Magician’”(Early China 15, 27-47).

- ↑ Theobald, Ulrich (2018). "Shang Period Economy".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Eno (2010b).

- ↑ Pankenier, David. "A Brief History of Beiji 北極 (Northern Culmen), With an Excursis on the Origin of the Character di 帝"". Journal of the American Oriental Society 124.2, 211-236).

- ↑ Eno (2008), p. 74.

- ↑ Smith, Adam Daniel (2010). "The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Origins of the Calendar". In Steele, John M. (ed.). Calendars and Years II: Astronomy and Time in the Ancient and Medieval World. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 1–37. doi:10.7916/D8891CDX. ISBN 978-7-5027-0532-9.

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Guo Moruo. Collection of Oracle bone Inscriptions (甲骨文合集).

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Chang, pp. 186 - 91

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Nivison, David S. (January 1999). "The key to the Chronology of the Three Dynasties: The "Modern Text" Bamboo Annals" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 93.

- ↑ Mizoguchi, Koji; Uchida, Junko (2018). "The Anyang Xibeigang Shang Royal Tombs Revisited: a Social Archaeological Approach". Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. 92 (363): 709–723. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.19.

- ↑ "规模宏大的安阳殷墟商代王陵(图)". Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Eno, Robert (2010). SHANG SOCIETY.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Eno, Robert (2010). SHANG SOCIETY.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Smith, Adam (2010). The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Foundations of the Calendar.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Sources

- Eno, Robert (2008). "Shang State Religion and the Pantheon of the Oracle Texts". In Lagerwey, John; Kalinowski, Marc (eds.). Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC-220 AD). Brill. pp. 41–102. ISBN 978-9004168350.

- Eno, Robert (2010a). "History G380: Shang Religion" (PDF). Indiana University.

- Eno, Robert (2010b). "History G380: Shang Society" (PDF). Indiana University.

- Keightley, David N. (1999). "The Shang: China's first historical dynasty". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–291.

- Keightley, David N. (2004). "The Making of the Ancestors: Late Shang Religion and Its Legacy"". In Lagerwey, John (ed.). Chinese Religion and Society: The Transformation of a Field. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. pp. 3–63.