The global warming controversy (or climate change debates) concerns past or present public debates over certain aspects of climate change: whether it is occurring (climate change deniers dispute this), how much has occurred in modern times, what has caused it (attribution of climate change), what its effects will be, whether action should be taken to curb it now or later, and so forth. In the scientific literature, there is a very strong consensus that global surface temperatures have increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.[1]

The controversy is, by now, mostly political rather than scientific: there is a scientific consensus that global warming is happening and is caused by human activity.[2] Public debates that also reflect scientific debate include estimates of how responsive the climate system might be to any given level of greenhouse gases (climate sensitivity). Disputes over the key scientific facts of global warming are more prevalent in the media than in the scientific literature, where such issues are treated as resolved, and such disputes are more prevalent in the United States and Australia than globally.[3][4][5]

Climate change remains an issue of widespread political debate, often split along party political lines, especially in the United States.[6]

Debates around the processes of IPCC

Deniers have generally attacked either the IPCC's processes, scientist or the synthesis and executive summaries; the full reports attract less attention. Some of the criticism has originated from experts invited by the IPCC to submit reports or serve on its panels. For example, John Christy, a contributing author who works at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, explained in 2007 the difficulties of establishing scientific consensus on the precise extent of human action on climate change:

Contributing authors essentially are asked to contribute a little text at the beginning and to review the first two drafts. We have no control over editing decisions. Even less influence is granted the 2,000 or so reviewers. Thus, to say that 800 contributing authors or 2,000 reviewers reached consensus on anything describes a situation that is not reality.[7]

Christopher Landsea, a hurricane researcher, said of "the part of the IPCC to which my expertise is relevant" that "I personally cannot in good faith continue to contribute to a process that I view as both being motivated by pre-conceived agendas and being scientifically unsound,"[8] because of comments made at a press conference by Kevin Trenberth of which Landsea disapproved. Trenberth said "Landsea's comments were not correct";[9] the IPCC replied "individual scientists can do what they wish in their own rights, as long as they are not saying anything on behalf of the IPCC".[10]

In 2005, the House of Lords Economics Committee wrote, "We have some concerns about the objectivity of the IPCC process, with some of its emissions scenarios and summary documentation apparently influenced by political considerations." It doubted the high emission scenarios and said that the IPCC had "played-down" what the committee called "some positive aspects of global warming".[11] The main statements of the House of Lords Economics Committee were rejected in the response made by the United Kingdom government.[12]

On 10 December 2008, a report was released by the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works Minority members, under the leadership of the Senate's most vocal global warming denier Jim Inhofe. It says it summarizes scientific dissent from the IPCC.[13] Many of its statements about the numbers of individuals listed in the report, whether they are actually scientists, and whether they support the positions attributed to them, have been disputed.[14][15][16]

Debates around details in the science

Discussions around locations of temperature measurement stations

There have been attempts to raise public controversy over the accuracy of the instrumental temperature record on the basis of the urban heat island effect, the quality of the surface station network, and assertions that there have been unwarranted adjustments to the temperature record.[17][18]

Weather stations that are used to compute global temperature records are not evenly distributed over the planet, and their distribution has changed over time. There were a small number of weather stations in the 1850s, and the number did not reach the current 3000+ until the 1951 to 1990 period[19]

The 2001 IPCC Third Assessment Report (TAR) acknowledged that the urban heat island is an important local effect, but cited analyses of historical data indicating that the effect of the urban heat island on the global temperature trend is no more than 0.05 °C (0.09 °F) degrees through 1990.[20] Peterson (2003) found no difference between the warming observed in urban and rural areas.[21]

Parker (2006) found that there was no difference in warming between calm and windy nights. Since the urban heat island effect is strongest for calm nights and is weak or absent on windy nights, this was taken as evidence that global temperature trends are not significantly contaminated by urban effects.[22] Pielke and Matsui published a paper disagreeing with Parker's conclusions.[23]

In 2005, Roger A. Pielke and Stephen McIntyre criticized the US instrumental temperature record and adjustments to it, and Pielke and others criticized the poor quality siting of a number of weather stations in the United States.[24][25] A study in 2010 examined the siting of temperature stations and found that those measurement stations that were poorly showed a slight cool bias rather than the warm bias which deniers had postulated.[26][27]

The Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature group carried out an independent assessment of land temperature records, which examined issues raised by deniers, such as the urban heat island effect, poor station quality, and the risk of data selection bias. The preliminary results, made public in October 2011, found that these factors had not biased the results obtained by NOAA, the Hadley Centre together with the Climatic Research Unit (HadCRUT) and NASA's GISS in earlier studies. The group also confirmed that over the past 50 years the land surface warmed by 0.911 °C, and their results closely matched those obtained from these earlier studies.[28][29][30][31]

Apparent discrepancy for tropospheric temperature increases in the tropics

General circulation models and basic physical considerations predict that in the tropics the temperature of the troposphere should increase more rapidly than the temperature of the surface. A 2006 report to the U.S. Climate Change Science Program noted that models and observations agreed on this amplification for monthly and interannual time scales but not for decadal time scales in most observed data sets. Improved measurement and analysis techniques have reconciled this discrepancy: corrected buoy and satellite surface temperatures are slightly cooler and corrected satellite and radiosonde measurements of the tropical troposphere are slightly warmer.[32] Satellite temperature measurements show that tropospheric temperatures are increasing with "rates similar to those of the surface temperature", leading the IPCC to conclude in 2007 that this discrepancy is reconciled.[33]

"Antarctica cooling controversy"

The Antarctica cooling controversy was the result of an apparent contradiction in the observed cooling behavior of Antarctica between 1966 and 2000, which became part of the public debate in the global warming controversy, particularly between advocacy groups of both sides in the public arena[34] including politicians,[35] as well as the popular media.[36][37] In contrast to the popular press, there is no similar controversy within the scientific community,[38] as the small observed changes in Antarctica are consistent with the small changes predicted by climate models, and because the overall trend since comprehensive observations began is now known to be one of warming. Observations unambiguously show the Antarctic Peninsula to be warming. The trends elsewhere show both warming and cooling but are smaller and dependent on season and the timespan over which the trend is computed.[39]

A study released in 2009 combined historical weather station data with satellite measurements to deduce past temperatures over large regions of the continent, and these temperatures indicate an overall warming trend. One of the paper's authors stated, "We now see warming is taking place on all seven of the earth's continents in accord with what models predict as a response to greenhouse gases."[40] According to a 2011 paper by Ding, et al., "The Pacific sector of Antarctica, including both the Antarctic Peninsula and continental West Antarctica, has experienced substantial warming in the past 30 years."[41][42]

This controversy began with the misinterpretation of the results of a 2002 paper by Doran et al.,[43][44] which found "Although previous reports suggest slight recent continental warming, our spatial analysis of Antarctic meteorological data demonstrates a net cooling on the Antarctic continent between 1966 and 2000, particularly during summer and autumn."[43] In his novel State of Fear, Michael Crichton asserted that the Antarctic data contradicted global warming.[45] The few scientists who have commented on the supposed controversy state that there is no contradiction,[46] while the author of the paper whose work inspired Crichton's remarks has said that Crichton misused his results.[47]Global dimming

Forecasts confidence

The IPCC stated in 2010 it has increased confidence in forecasts coming from General Circulation Models:

There is considerable confidence that climate models provide credible quantitative estimates of future climate change, particularly at continental scales and above. This confidence comes from the foundation of the models in accepted physical principles and from their ability to reproduce observed features of current climate and past climate changes. Confidence in model estimates is higher for some climate variables (e.g., temperature) than for others (e.g., precipitation). Over several decades of development, models have consistently provided a robust and unambiguous picture of significant climate warming in response to increasing greenhouse gases.[53]

A few scientists believe this confidence in the models' ability to predict future climate is not earned.[54]

Debates over most effective response to warming

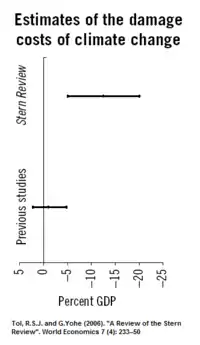

The economic analysis of climate change explains how economic thinking, tools and techniques are applied to calculate the magnitude and distribution of damage caused by climate change. It also informs the policies and approaches for mitigation and adaptation to climate change from global to household scales. This topic is also inclusive of alternative economic approaches, including ecological economics and degrowth. In a cost–benefit analysis, the trade offs between climate change impacts, adaptation, and mitigation are made explicit. Cost–benefit analyses of climate change are produced using integrated assessment models (IAMs), which incorporate aspects of the natural, social, and economic sciences. The total economic impacts from climate change are difficult to estimate, but increase for higher temperature changes.[55]

Climate change impacts can be measured as an economic cost.[56]: 936–941 This is particularly well-suited to market impacts, that is impacts that are linked to market transactions and directly affect GDP. However, monetary measures of non-market impacts, e.g., impacts on human health and ecosystems, are more difficult to calculate. Economic analysis of climate change is challenging as it is a long-term problem and has substantial distributional issues within and across countries. Furthermore, it engages with uncertainty about the physical damages of climate changes, human responses, and future socioeconomic development.

In most models, benefits exceed costs for stabilization of GHGs leading to warming of 2.5 °C. No models suggest that the optimal policy is to do nothing, i.e., allow "business-as-usual" emissions.

Sub-topics within the economic analysis concept are the economic impacts of climate change, as well as the economics of climate change mitigation. Climate change mitigation consist of human actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or to enhance carbon sinks that absorb greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.[57]: 2239See also

References

- ↑ "'Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis.' IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Working Group I, Summary for Policymakers. 'The best estimate of the human-induced contribution to warming is similar to the observed warming over this period.'" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ↑ "Scientific consensus: Earth's climate is warming". Climate Change: Vital Signs of the Planet. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ↑ Stoddard, Isak; Anderson, Kevin; Capstick, Stuart; Carton, Wim; Depledge, Joanna; Facer, Keri; Gough, Clair; Hache, Frederic; Hoolohan, Claire; Hultman, Martin; Hällström, Niclas; Kartha, Sivan; Klinsky, Sonja; Kuchler, Magdalena; Lövbrand, Eva; Nasiritousi, Naghmeh; Newell, Peter; Peters, Glen P.; Sokona, Youba; Stirling, Andy; Stilwell, Matthew; Spash, Clive L.; Williams, Mariama; et al. (18 October 2021). "Three Decades of Climate Mitigation: Why Haven't We Bent the Global Emissions Curve?". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 46 (1): 653–689. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012220-011104. hdl:1983/93c742bc-4895-42ac-be81-535f36c5039d. ISSN 1543-5938. S2CID 233815004. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ↑ Boykoff, M.; Boykoff, J. (July 2004). "Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press" (PDF). Global Environmental Change Part A. 14 (2): 125–136. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2015.

- ↑ Oreskes, Naomi; Conway, Erik (2010). Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming (first ed.). Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-610-4.

- ↑ Public Support for Climate and Energy Policies in March 2012 (PDF). Yale Project on Climate Change Communication. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ "Written testimony of John R. Christy Ph.D. before House Committee on Energy and Commerce on March 7, 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ↑ "An Open Letter to the Community from Chris Landsea". Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ↑ "Prometheus: Final Chapter, Hurricanes and IPCC, Book IV Archives". Sciencepolicy.colorado.edu. 14 February 2007. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "Hurricanes and Global Warming for IPCC" (PDF). Washington. Reuters. 21 October 2004. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ↑ "Final Climate Change Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

- ↑ The Committee Office, House of Lords (28 November 2005). "House of Lords – Economic Affairs – Third Report". Publications.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ "UN Blowback: More Than 650 International Scientists Dissent Over Man-Made Global Warming Claims". www.epw.senate.gov. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ↑ "How many on Inhofe's list are IPCC authors?". Archived from the original on 27 January 2012.

- ↑ "More on Inhofe's alleged list of 650 scientists". Archived from the original on 22 January 2012.

- ↑ "Inhofe's 650 "dissenters" (make That 649... 648...)". The New Republic. 15 December 2008.

- ↑ EPA (12 August 2013). "Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases under the Clean Air Act – EPA's Denial of Petitions for Reconsideration, Volume 1: Climate Science and Data Issues Raised by Petitioners". www.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ↑ "EPA's Denial of the Petitions To Reconsider the Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases Under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act". Federal Register. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ↑ "Temperature data (HadCRUT, CRUTEM,, HadCRUT5, CRUTEM5) Climatic Research Unit global temperature".

- ↑ J.R. Christy, R.A. Clarke, G.V. Gruza, J. Jouzel, M.E. Mann, J. Oerlemans, M.J. Salinger, S.-W. Wang (2001) Chapter 2: Observed Climate Variability and Change, Working Group 1 Contribution to TAR Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas C. (2003). "Assessment of urban versus rural in situ surface temperatures in the contiguous United States: no difference found". Journal of Climate (Submitted manuscript). 16 (18): 2941–59. Bibcode:2003JCli...16.2941P. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016<2941:AOUVRI>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0442. S2CID 32302840.

- ↑ David, Parker (2006). "A demonstration that large-scale warming is not urban". Journal of Climate. 19 (12): 2882–95. Bibcode:2006JCli...19.2882P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.543.2675. doi:10.1175/JCLI3730.1.

- ↑ Pielke Sr., R.A.; T. Matsui (2005). "Should light wind and windy nights have the same temperature trends at individual levels even if the boundary layer averaged heat content change is the same?" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 32 (21): L21813. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3221813P. doi:10.1029/2005GL024407. S2CID 3773490. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008.

- ↑ Davey, Christopher A.; Pielke, Roger A. Sr. (2005). "Microclimate Exposures of Surface-Based Weather Stations: Implications For The Assessment of Long-Term Temperature Trends" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 86 (4): 497–504. Bibcode:2005BAMS...86..497D. doi:10.1175/BAMS-86-4-497. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008.

- ↑ Mahmood, Rezaul; Stuart A. Foster; David Logan (2006). "The GeoProfile metadata, exposure of instruments, and measurement bias in climatic record revisited". International Journal of Climatology. 26 (8): 1091–1124. Bibcode:2006IJCli..26.1091M. doi:10.1002/joc.1298. S2CID 128889147.

- ↑ Menne, Matthew J.; Claude N. Williams, Jr.; Michael A. Palecki (2010). "On the reliability of the U.S. surface temperature record" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 115 (D11): D11108. Bibcode:2010JGRD..11511108M. doi:10.1029/2009JD013094.

In summary, we find no evidence that the CONUS average temperature trends are inflated due to poor station siting...The reason why station exposure does not play an obvious role in temperature trends probably warrants further investigation.

- ↑ Cook, John (27 January 2010). "Climate sceptics distract us from the scientific realities of global warming". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ Jeff Tollefson (20 October 2011). "Different method, same result: global warming is real". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2011.607. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "Cooling the Warming Debate: Major New Analysis Confirms That Global Warming Is Real". Science Daily. 21 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ Ian Sample (20 October 2011). "Global warming study finds no grounds for climate sceptics' concerns". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "Climate change: The heat is on". The Economist. 22 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ Santer, B. D.; Thorne, P. W.; Haimberger, L.; K. E. Taylor; T. M. L. Wigley; J. R. Lanzante; S. Solomon; M. Free; P. J. Gleckler; P. D. Jones; T. R. Karl; S. A. Klein; C. Mears; D. Nychka; G. A. Schmidt; S. C. Sherwood; F. J. Wentz (2008). "Consistency of modelled and observed temperature trends in the tropical troposphere" (PDF). International Journal of Climatology. 28 (13): 1703–22. Bibcode:2008IJCli..28.1703S. doi:10.1002/joc.1756. S2CID 14941858.

- ↑ IPCC, 2007: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M.Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- ↑ Peter N. Spotts (18 January 2002). "Guess what? Antarctica's getting colder, not warmer". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ "America Reacts To Speech Debunking Media Global Warming Alarmism". U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works. 28 September 2006. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Davidson, Keay (4 February 2002). "Media goofed on Antarctic data / Global warming interpretation irks scientists". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Bijal P. Trivedi (25 January 2002). "Antarctica Gives Mixed Signals on Warming". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 28 January 2002. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Davidson, Keay (4 February 2002). "Media goofed on Antarctic data / Global warming interpretation irks scientists". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Chapman WL, Walsh JE (2007). "A Synthesis of Antarctic Temperatures". Journal of Climate. 20 (16): 4096–4117. Bibcode:2007JCli...20.4096C. doi:10.1175/JCLI4236.1.

- ↑ Kenneth Chang (21 January 2009). "Warming in Antarctica Looks Certain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Ding, Qinghua; Eric J. Steig; David S. Battisti; Marcel Küttel (10 April 2011). "Winter warming in West Antarctica caused by central tropical Pacific warming". Nature Geoscience. 4 (6): 398–403. Bibcode:2011NatGe...4..398D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.459.8689. doi:10.1038/ngeo1129.

- ↑ "Antarctic cooling pushing life closer to the edge". USA Today. 16 January 2002. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- 1 2 Doran PT; Priscu JC; Lyons WB; et al. (January 2002). "Antarctic climate cooling and terrestrial ecosystem response" (PDF). Nature. 415 (6871): 517–20. doi:10.1038/nature710. PMID 11793010. S2CID 387284. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2004.

- ↑ Doran; et al. (13 January 2002). "Antarctic climate cooling and terrestrial ecosystem response" (PDF). Nature. University of Illinois at Chicago. 415 (6871): 517–20. doi:10.1038/nature710. PMID 11793010. S2CID 387284. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2013. PDF version: advance online publication Letters to Science (archived original)

- ↑ Crichton, Michael (2004). State of Fear. HarperCollins, New York. pp. 109. ISBN 978-0-06-621413-9. First Edition

- ↑ Eric Steig; Gavin Schmidt (3 December 2004). "Antarctic cooling, global warming?". Real Climate. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- ↑ Peter Doran (27 July 2006). "Cold, Hard Facts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- 1 2 Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Di Luca, A.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; Otto, F.; Pinto, I.; Satoh, M.; Vicente-Serrano, S. M.; Wehner, M.; Zhou, B. (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Piran, A.; Connors, S.L.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L. (eds.). "Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate" (PDF). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2021: 1238. Bibcode:2021AGUFM.U13B..05K. doi:10.1017/9781009157896.007.

- ↑ Eddy, John A.; Gilliland, Ronald L.; Hoyt, Douglas V. (23 December 1982). "Changes in the solar constant and climatic effects". Nature. 300 (5894): 689–693. Bibcode:1982Natur.300..689E. doi:10.1038/300689a0. S2CID 4320853.

Spacecraft measurements have established that the total radiative output of the Sun varies at the 0.1−0.3% level

- ↑ Wild, Martin; Trüssel, Barbara; Ohmura, Atsumu; Long, Charles N.; König-Langlo, Gert; Dutton, Ellsworth G.; Tsvetkov, Anatoly (16 May 2009). "Global dimming and brightening: An update beyond 2000". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 114 (D10): D00D13. Bibcode:2009JGRD..114.0D13W. doi:10.1029/2008JD011382.

- ↑ He, Yanyi; Wang, Kaicun; Zhou, Chunlüe; Wild, Martin (19 April 2018). "A Revisit of Global Dimming and Brightening Based on the Sunshine Duration". Geophysical Research Letters. 6 (9): 6346. Bibcode:2018GeoRL..45.4281H. doi:10.1029/2018GL077424. hdl:20.500.11850/268470. S2CID 134001797.

- ↑ He, Yanyi; Wang, Kaicun; Zhou, Chunlüe; Wild, Martin (15 April 2022). "Evaluation of surface solar radiation trends over China since the 1960s in the CMIP6 models and potential impact of aerosol emissions". Atmospheric Research. 268: 105991. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2021.105991. S2CID 245483347.

- ↑ "Climate Models and Their Evaluation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ↑ Kesten C. Greene; J. Scott Armstrong (2007). "Global Warming: Forecasts by Scientists Versus Scientific Forecasts" (PDF). Energy & Environment. 18 (7): 997–1021. doi:10.1260/095830507782616887. S2CID 154566714. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010.

- ↑ Luomi, Mari (2020). Global Climate Change Governance: The search for effectiveness and universality (Report). International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). JSTOR resrep29269.

- ↑ Smith, J. B.; et al. (2001). "19. Vulnerability to Climate Change and Reasons for Concern: A Synthesis" (PDF). In McCarthy, J. J.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (PDF). Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 913–970. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ↑ IPCC, 2021: Annex VII: Glossary [Matthews, J.B.R., V. Möller, R. van Diemen, J.S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, S. Semenov, A. Reisinger (eds.)]. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2215–2256, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.022.