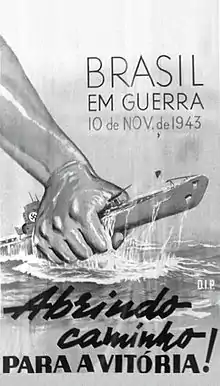

Brazil fought on the Allied side in World War II, (1939–1945) despite the fascist sympathies of its ruling Estado Novo regime. German and Italian submarines torpedoed Brazilian ships in February 1942 in retaliation for Brazil's adherence to the Atlantic Charter, which called for automatic support for any nation on the American continent who was attacked by an extra-continental power. Over several months they sank 36 Brazilian merchant ships, causing a total of 1,691 shipwrecks and 1,074 deaths.

Overview

Brazil's maritime losses were the primary reason for its declaration of war on Germany and Italy.[1] Its traditionally isolationist international policy automatically aligned it against "disturbers of the international order and trade". The people took to the streets and the Brazilian government declared war on Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in August 1942. In 1942, American economic incentives and diplomatic pressure led to the installation of airbases along the northeastern Brazilian coast.

The Brazilian population was largely rural and illiterate, and its economy focused on exporting commodities. It lacked the industrial, medical and educational infrastructure needed to support the war.[2] Not only could Brazil not pursue an autonomous course of action in the conflict, it had difficulty in making the smallest of efforts to assist in it.[3] For instance, the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, whose formation was defined at the Potenji River Conference soon after the Casablanca Conference, wasn't created until a year after the declaration of war.

They were deployed to the front in July 1944, almost two years after the declaration of war, and put under the the Allied 15th Army Group. Around 25,000 men were sent out of the 100,000 initially planned. Once in Italy, trained and equipped by the Americans, the Brazilian Expeditionary Force fulfilled the main missions assigned to it by the Allied command.

History

Predecessors

In February 1942, German and Italian submarines began to torpedo Brazilian vessels in the Atlantic Ocean, according to Goebbels' diaries, for adhering to its commitments under the Atlantic Charter (which provided for automatic alignment with any nation of the American continent that was attacked by an extra-continental power).

Of great importance for the Brazilian government was to gradually align itself with the United States and, consequently, and the Allied cause after Pearl Harbor, were: Germany and Italy's veiled attempts to interfere in Brazilian internal affairs, especially from the implementation of the Estado Novo. It became progressively more impossible, starting at the end of 1940, to maintain stable and effective trade relations with these countries due to British and later American naval pressure, and the ,Good Neighbor policy of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who, among other economic and commercial incentives, financed the construction of a steel mill, the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional (CSN).[4][5][6] Reports at the time said that the United States had planned to invade the northeast of Brazil (Plan Rubber) if Getúlio Vargas insisted on maintaining Brazil's neutrality.[7][8]

In 1942, after the United States proposed to finance the construction of CSN, among other economic assistance proposals, the Americans installed aircraft bases along the Brazilian North-Northeast coast. The most important of these was in the city of Parnamirim, near the capital Natal of Rio Grande do Norte. This base, called "Trampoline of Victory", was especially important to the Allied war effort before the Anglo-American landing in North Africa in November 1942, in Operation Torch. From the stabilization of the Italian front in late 1943 and the weakening of the German submarine campaign, the American bases on Brazilian soil were progressively deactivated in 1944-45, although the Americans remained on the island of Fernando de Noronha until 1960.[4]

Brazilian ships sunk

.

Attacks on the ships by Axis submarines between 1941 and 1944, caused the death of more than a thousand people and precipitated Brazil's entry into the conflict. Until then it had remained neutral. Thirty-five ships were attacked and 32 were sunk.[note 1] in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean. The other attacks occurred after Brazil broke off diplomatic relations with the Axis on January 28, 1942. The attacks peaked in August 1942, when in only two days, six ships were sunk, causing the death of more than 600 people, and leading Brazil to declare war on August 21.

In 1943, despite considerable improvement in patrolling and anti-submarine warfare systems in joint Brazilian and American operations, Axis "u-boats" still attacked throughout the South Atlantic, especially off the coasts of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Most of the vessels were merchant or mixed cargo and passenger ships, and belonged to big shipping companies - Lloyd Brasileiro, Lloyd Nacional, and Costeira.[note 2] Ships from small companies were also attacked,[note 3] as well as vessels owned by regional shipowners and seafarers, such as the barge Jacira, and the fishing boat Shangri-lá. Lloyd Brasileiro, the largest of these companies, arguably lost the most ships and crew members: There were 21 vessels attacked, and 19 of them were sunk.

The Brazilian Navy lost only one warship, the auxiliary ship Vital de Oliveira, en route to Rio de Janeiro after stops in the Northeast and Espírito Santo, also the last Brazilian ship torpedoed in World War II), to U-861 on July 19, 1944. The Brazilian Navy lost two more military ships in World War II: the corvette Camaquã, which capsized in a storm on July 21, 1944, when 23 crew members died; and the cruiser Bahia, which set off its own depth charges during gunnery practice and sank on July 4, 1945, killing 333 men. The Cabedelo and the Shangri-lá were the two ships that did not survive.[9]

"Atlantic Belt"

With the Suez Canal blocked, and the need for raw materials such as rubber and tin from Malaysia, the Germans and Italians used the Atlantic Ocean route to maintain their arms industry. Initially, it was their cruisers and large cargo ships that made the long voyage across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. As the risk of losing ships with great war potential became high due to blockades by the Allies, the Axis began using submarines and "blockade runners" (armed vessels disguised as merchant vessels, neutral or allied).

The "Atlantic Belt", the narrowest stretch between South America and Africa, was strengthened to hinder the influx of raw material to the enemy, especially, the 1,700-mile straight line from Natal to Dakar. The Allies called the route ending in Brazil the "Northeast Ridge",[10] For this to happen, bases had to be installed in Brazil, which began in mid-June 1941, when Task Force No. 3 arrived and the ports of Recife and Salvador were cleared for use by the US Navy. In turn, the Axis tried to interrupt shipments of raw materials to the United States and England, thus beginning the attack on merchant vessels sailing through the Atlantic.[11]

Beginning of hostilities

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Brazil |

|---|

|

|

|

On March 22, the merchant ship Taubaté was attacked by a German aircraft in the Mediterranean, off the Egyptian coast. In this episode, Brazil had its first war casualty, the gate clerk José Francisco Fraga.[12] On June 13, a German submarine stopped the merchant ship Siqueira Campos, near the Cape Verde archipelago, with cannon fire, and only released it after inspecting it.[13] Since 1940, Brazilian ships had been seized three times: (the Siqueira Campos, the Buarque, and the Itapé) by the British, under different pretexts, especially for transporting goods and/or passengers of German origin. On January 18, 1941, the French merchant ship Mendoza was captured in the safety zone waters off the Brazilian coast by a British auxiliary cruiser. This incident led the Brazilian government to send a protest note to the British government.[note 4]

The rupture of diplomatic relations and the American bases in the Northeast made Brazil a hostile country in the eyes of the Germans and Italians, in the words of German ambassador Pruefer, "in a state of latent war" with the Axis.[11][14] From then on, Brazilian ships were attacked off the American coast and in the Caribbean. The first was the Buarque (one killed) and the Olinda (no casualties), on February 15 and 18, 1942, respectively. The most emblematic case, and also the most tragic until then, was the "disappearance" of the Cabedelo, somewhere in the Atlantic east of the Caribbean, after setting sail from the United States on February 14, when at the peak the submarine offensive. Fifty-four men died and it is not known who sank the ship. The most likely hypothesis is that it was the Italian submarine Da Vinci, but there is no definitive proof. The possibility that the Cabedelo was torpedoed by other Italian submarines: the Torelli[15] or the Capellini has also been considered.[16] The date of the sinking is also controversial. Some sources consider say the 14th, the day it left the United States.[10][11] Others say February 25.[9][13][15]

By the end of July, Brazil had also lost:

- The SS Arabutan (one dead).

- The Cairu (fifty-three dead).

- The Parnaíba (seven dead).

- The Gonçalves Dias (six dead).

- The Alegrete (no casualties).

- The Paracuri (no data on the number of people on board, or if there were casualties).

- The Pedrinhas (no casualties).

- The Tamandaré (four dead).

- The Barbacena (six dead).

- The Piave (one dead).

All were attacked far from the Brazilian coast, and except for the Cairu, the number of casualties was not catastrophic. Many shipwrecks of national merchant ships were interrogated by commanders and crew of the German U-boats, interested in the voyages of other vessels and the cargoes taken to the United States.

Attacks in the South Atlantic

On May 18, the Italian submarine Barbarigo made the first attack in the South Atlantic basin, close to Brazil's national waters, against the freighter Commander Lira. The ship was traveling from Recife to New Orleans when it was torpedoed 180 nautical miles off the Fernando de Noronha archipelago. The crew sent an SOS signal and abandoned the vessel, which was also shelled, and left burning after Barbarigo pulled away, believing that its target would soon sink. But the SOS had been picked up by American ships, and on the morning of 19 May, sailors from the American light cruiser USS Omaha boarded Commander Lira and put out the fire. The merchant crew needed to steer the ship were taken back on board, and the ship was towed by the small American minesweaper USS Thrush, in conjunction with the Brazilian Navy tug Heitor Perdigão, to Fortaleza, arriving 25 May.[17] The episode was a diplomatic triumph for the US, helping turn Brazilian opinion against the Axis.

Two days after attacking Commander Lira, Barbarigo attacked what its commander thought was an American battleship, and reported sinking it. It was actually the cruiser USS Milwaukee, which was not hit.[10]

After these episodes, Barbarigo was attacked between the Rocas Atoll and Fernando de Noronha by a B-25 Mitchell bomber of the newly created Brazilian Air Force (FAB). The plane belonged to the Adaptation Aircraft Grouping, a training unit that the FAB had organized to receive planes from the United States. The crew of the B-25 was mixed American and Brazilian. Captain Affonso Celso Parreiras Horta was in command, and the other Brazilian officer on board was Captain Oswaldo Pamplona Pinto. The American pilot training them was First Lieutenant Henry B. Schwane of the US Army Air Force. This would be the first combat mission in the history of the FAB.[10]

At the same time, three other Italian submarines were in action off the coast of Brazil: Archimede, Cappellini, and Bagnolini. Archimede attacked the convoy of Commander Lira. Although the attack did no damage, her captain thought he had sunk a heavy cruiser, likely mistaking for a torpedo hit the detonation of a depth charge from the destroyer USS Moffett. The events of that week were widely reported; US President Roosevelt congratulated Brazilian President Vargas for Brazilian attacks on the submarines.[10]

By July, Brazil had lost 14 ships (not counting Taubaté, machine-gunned down the year before). On 7 August 1942, Befehlshaber der U-Boote (the German submarine command) ordered submarines in the South Atlantic, among them U-507 (commanded by Captain Harro Schacht), to attack all ships that sailed into Brazilian waters, except those that were Argentine and Chilean.[10] Brazil was still neutral, but in that month considerable US forces had already established themselves in Northeast Brazil.

Another sign of the end of neutrality were the attacks on Italian submarines in May, and the order to place cannons on merchant ships that had been armed since that May.[10] In four days (August 15-19), U-507, sailing close to the coasts of Bahia and Sergipe, sank five coasting ships and another small boat, causing 607 casualties, including many women and children.[14] This caused indignation and consternation among the Brazilian public, and led to formal declaration of war against the Axis powers at the end of August. Many other attacks by enemy forces took place afterward, which also took many lives. They were: Baependi (270 killed), Araraquara (131 killed), Aníbal Benévolo (150 killed), Itagiba (36 dead), and Arará (20 dead).[10][14][18]

Popular response

In a matter of days, the number of dead had more than quadrupled from those since the beginning of the year (607 versus 135). Moreover, the other ships had generally been attacked far from the country; and their victims, for the most part, were sailors. Only seven passengers had died in the first 13 sinkings, 6 of them on the Cairu. The photos of the dead on the beaches, and the accounts of the survivors made the population realize that war had indeed come to the country. "Challenge and outrage to Brazil", was the headline of O Globo on the 18th of August. By then, the number of victims had already exceeded six hundred. Panic erupted among the population, especially those who needed to travel from one state to another. There were no highways or railroads connecting the regions of the country and crossing great distances. Civil aviation was incipient and there were virtually no airports.[14]

For these people, one of the only and cheapest options available was to use ships. It was common for merchant ships to carry passengers, who took advantage of the stopovers to travel from one point to another in the country. Thus, any Brazilian family traveling by ship at that time ran the risk of being a victim of a submarine attack. And for those who lived on the coast of the Northeast, the war did not seem as distant a reality as it might have seemed to Brazilians in other regions. With time, the initial commotion and panic gave way to general indignation. In 1942 Rio de Janeiro, a series of marches and popular rallies were held, in which the population demanded retaliation; they headed to the Itamaraty Palace - headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs - clamoring for Chancellor Oswaldo Aranha, who exclaimed to the people:[14]

"The situation created by Germany, practicing belligerent, barbaric and inhumane acts against our peaceful and coastal navigation, imposes a reaction at the level of the processes and methods employed by them against Brazilian officers, soldiers, women, children and ships. I can assure the Brazilians who are listening to me, as to all Brazilians, that, compelled by the brutality of the aggression, we will oppose a reaction that will serve as an example to the aggressor and barbaric peoples, who violate the civilization and the life of peaceful peoples."

The National Union of Students (UNE) organized marches in the main Brazilian cities, demanding that the country enter the war on the side of the Allies. In these marches, it was common for some students to dress up as Hitler, with the objective of ridiculing the Nazi dictator. These marches ended up receiving a large popular support, not only from university students but also from other sectors of the population, who also demanded war.[15] This forced the reluctant government of Getúlio Vargas to enter the war. On August 22, after a ministerial meeting, Brazil declared a "state of belligerency" against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy,[note 5] formalized by Decree-Law 10,508, issued on August 31.

Controversial cases

During the conflict, other Brazilian ships were shipwrecked, mostly by collision or stranding. Some cases, however, were never clarified, such as the disappearance of the Santa Clara, near Bermuda, on March 15, 1941, and the sinking of the Cisne Branco, on September 27, 1943. The sinking of the Cisne Branco is sometimes credited to the German submarine U-161,[9][17] but, on the day of the sinking, this submarine was off the coast of Alagoas - approximately 750 km away - which rules out its participation in that event, although it is plausible that another submarine could have attacked that ship.

The Brazilian courts, in 2005, granted a survivor of the ship the right to receive the special pension for former combatants of World War II, assured in the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, although the court decision was based on the fact that the ship was involved in the war effort - it provided supply service for the Navy - and not that it was effectively torpedoed by enemy action. For this reason, the crew members killed in the sinking (the number varies between one and four) could not have their names inscribed on the Monument to the Dead of World War II. Regarding Santa Clara, it is known that the ship, on a voyage from New York to Rio de Janeiro, would have suffered an explosion on board, and that its crew had abandoned it. However, nothing but wreckage of the ship has been found. The crew and lifeboats were never located.[19]

There is also mention of the sinking of two unidentified Brazilian vessels: One on June 5, 1942, in the Caribbean, sunk by U-159, together with the Brazilian sailboat Paracuri; and the other, sunk by U-507, on August 17 of the same year.[9][17] Regarding the first one, it is probable that the unidentified vessel was the Honduran sailboat Sally, a small vessel of 150 tons, which was proven to have been torpedoed by the U-159. As for the second event, there was likely a mistake, as on August 17, 1942, according to official records, the U-507 sank two (and not three) ships: the Itagiba and the Arará, which were sunk almost simultaneously. The next Brazilian victim of the U-507 would be the small barge Jacira, which sunk two days later. It is plausible that the unidentified boat was one of those that came to the rescue of the double torpedoing, the yacht Aragipe and the schooner Deus do Mar, which were not attacked by the u-boat.[note 6][20]

Demonstrations against immigrants from Axis countries

After the sinking of the Brazilian ships and the high number of deaths, violent popular demonstrations against immigrants from the Axis countries, especially Germans, Japanese, and Italians, took place in several cities. There were many episodes of depredation of commercial establishments belonging to immigrants from countries that were part of the Axis - and even attempts to lynch such people.[15] After Brazil entered the war, many of these immigrants began to be watched by Brazilian authorities as part of the conflicts involving the "home front" of the war. Brazil was the scene of intense espionage activity during the war, and many immigrants who did not speak Portuguese were considered suspects of espionage.[21][22]

It was also in the midst of this process that newspapers and radio programs in the languages of the Axis countries were banned in Brazil. The Brazilian government created prisons for foreigners suspected of anti-Brazilian activities, which also served for prisoners coming from the crew of German vessels captured or damaged off the Brazilian coast. The Brazilian government's concern was linked to the Axis powers' use of the ties they had with immigrants and their Brazilian descendants, as countries like Germany, Italy, and Japan tried to mobilize and manipulate their emigrants in their favor in the war.[21][22] War propaganda on the home front was successful to the point that in the Japanese case, after the end of the conflict, 80% of the 200,000 Japanese immigrants and descendants living in São Paulo believed that Japan had won the war.[23]

Despite the existence of terrorist groups such as the Shindo Renmei that were active against the Brazilian government during World War II and executed Japanese immigrants favorable to Brazil; the intense activity of fascist groups favorable to the Axis countries; and the controversy regarding the arbitrariness with which immigrants were treated during the war, Japanese immigrants were better treated in Brazil than in other allied countries, such as the United States, where the approximately 120,000 Japanese immigrants, regardless of whether they were American citizens, were sent to concentration camps with precarious conditions.[15]

At the time, German and Italian immigrant groups in Brazil spread rumors that American submarines were responsible for the attacks, to force Brazil to enter the war. According to historians, this was a rumor created by the war propaganda of the Axis collaborators infiltrating the Brazilian population, called the "Fifth Columns". There is ample documentation proving that German submarines were responsible for torpedoing most Brazilian ships during World War II. The main reason for the rumors is that the raw materials carried by Brazilian merchant ships were of vital importance to the Allies, making the Axis countries interested in attacking these ships. Moreover, at that time, most of the American submarine fleet was not in the Atlantic Ocean, but in the Pacific, torpedoing Japanese warships.[15]

In this regard, Adm. Arthur Oscar Saldanha da Gama, ex-combatant and naval historian verified in the archives of the German Submarine Command the records of the sinking of Brazilian ships by their submarines, with respective names, positions and circumstances, thus dispelling any doubt about the authorship of the attacks.[24][25] In all, 66 attacks by the Brazilian Navy on German submarines in the South Atlantic were recorded, resulting in damage to or the sinking of 18 submarines off the Brazilian coast, of which nine - the U-128, U-161, U-164, U-199, U-513, U-590, U-591, U-598 and the U-662 - were officially recorded by the German Navy as having been sunk by the Brazilian Navy.[26] The German Navy also recorded the sinking of the Brazilian submarines.

Entry into the war

Brazil entered the war through decree No. 10.358 of August 31, 1942,[27] recognizing the state of war between Brazil and the Axis powers in August 1942.

The deployment of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (FEB) to the front began in July 1944, almost two years after the declaration of war. About 25,000 men were sent out of the 100,000 who were expected. Despite problems in preparation and deployment, already in Italy, trained and equipped by the Americans, the FEB fulfilled the main missions assigned to it by the allied command. However, Brazil's participation in the war and the way it unfolded contributed decisively to the end of the Estado Novo regime.[1]

Brazil's participation was more vigorous than the participation in World War I, considering the political and diplomatic game waged between Americans and Germans for Brazilian support, and the numbers of the real tactical and strategic contribution that the country provided compared to those of other allied countries (the FEB, for example, was one among 20 allied divisions in Italy, having acted in a sector, although relatively important, secondary in the Italian front, at a time when this very front had become of less importance to both sides. The still modest Brazilian participation in World War II can be equated to that of Japan in World War I. If on one hand, in numerical and tactical terms, the Brazilians had a greater participation in the Allied cause in the Second World War than the Japanese three decades earlier, on the other hand, the Japanese, between the 1920s and 1930s, were able to better capitalize politically and strategically at the international level on their participation in the 1914-18 conflict.[1][3]

Air force

The support offered by Brazil to the allies through the 1st Fighter Aviation Group, created on December 18, 1943, was of great importance. After a training period in Aguadulce, Panama, flying the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, where they participated in the Panama Canal defense campaign, the Brazilian pilots, all volunteers, went to Suffolk in England, where they were introduced to the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. Afterward, the group, which became known as Senta a Pua! was sent to northern Italy.[28]

Operations began on October 31, 1944, at the Tarquinia airfield, then moved to Pisa, closer to action, where the Group remained until the end of the war, being subordinated to the 350th Fighter Group of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), where it received the codename "Jambock".[28] On February 10, 1945, a squadron of the 1st G.Av.Ca. returning from a mission discovered a large concentration of trucks, destroying 80 of them and 3 buildings. On February 20, the Group helped the FEB in the conquest of Monte Castelo. On March 21, another victory, in the attack on a railroad repair shop, in the Po Valley: A direct hit destroyed four buildings and the return flight destroyed 3 Savoia-Marchetti SM.79, in the Galarate Field.[28]

The Group initially consisted of 4 squadrons, in the colors red (letter A painted on the plane), yellow (B), blue (C), and green (D). Later, due to the large number of casualties in the yellow squadron, only three remained. The missions given to the Brazilians involved attacking bridges, ammunition depots, and transport vehicles. There were no problems regarding air superiority in this region, held by the Allies, the major concern being anti-aircraft artillery.[28] Among the pilot officers who exercised aerial activities in the Group, a total of 48, there were 22 casualties, in addition to 4 more officers, victims of aviation accidents.[28]

Attacks against Brazilian ships after the declaration of war

A little over a month after the most tragic sinking, and less than a month after the declaration of war, three more ships would be targeted by the U-Boats: The Osório (5 dead), the Lajes (3 dead) and the Antonico (16 dead). The first two were torpedoed by the U-514 off Marajó Island; the third was sunk further north, off French Guiana, by the U-516. As a result of this act, at the end of the war, Brazil tried unsuccessfully to have the commander of the U-516, Captain lieutenant Gerhard Wiebe, and Lieutenant Markle, who fired shots at the shipwrecked men, extradited to Brazil for war crimes.[29] The Porto Alegre was sunk on November 3, off the Indian coast of South Africa, with one fatality. The year would end with the sinking of the Apalóide on November 22, west of the Lesser Antilles, causing five more deaths.[29]

The year 1943 began with good news to the Brazilians: The U-507, responsible for the August massacre of the previous year, had been sunk on January 13, in the Atlantic Ocean, about 100 miles off the coast of Ceará, by depth charges from a Catalina airplane, causing the death of all its 54 crew members. However, other ships would succumb to the other U-Boats still operating off the Brazilian coast. On February 18, it was the turn of the Brasilóide, torpedoed by the U-518 off the coast of Bahia. There were no fatalities in this sinking, but the following day, March 2, the war claimed the lives of 125 people aboard the Afonso Pena, sunk by the Italian submarine Barbarigo off Porto Seguro.[29]

On the same day, the Natal Air Base (BANT) was created at the then Parnamirim Field, later known as "Trampolim da Vitória" ("Trampoline of Victory"). The activities of the Natal Air Base would only begin on August 7 of the same year.[29]

Other Brazilian vessels hit during the war were:

- Tutoia, on the first of July (7 killed).

- Pelotaslóide (5 casualties), hit by the U-590 on 4 July.

- Shangri-la, on the 22nd of July (10 killed).

- Bagé, on the 31st of July (28 casualties).

- Itapagé, on the 26th of September (22 killed).

- Cisne Branco, on the following day (4 dead).

- Campos on the 23rd of October (12 dead).

By this time, the U-Boats were already suffering heavy casualties, not only on the Brazilian coasts but also in other places. In fact, in addition to the convoy system (the armament placed in merchant ships), the South Atlantic Force was created, with headquarters in Recife, as well as support bases in Natal and Fernando de Noronha. Air patrols began to be more effective at the end of December 1942, with American and FAB aircraft groups. The naval fleet was reinforced with the presence of American vessels. These patrols, allied with the deciphering of codes allowed results to be quickly harvested. The following year, Brazil still suffered the loss of the Vital de Oliveira, their only military ship sunk by enemy action in the war. The sinking, which occurred on July 20, 1944, off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, cost the lives of 99 people.[29]

The submarines sunk in Brazilian territorial waters were U-590; U-662; U-507; U-164; U-598; U-591; U-128; U-161; U-199; U-513 and Archimede.[30][31]

Post-war period

According to historian Frank McCann,[32] Brazil was invited to join the occupation force in Austria.[33] But the Brazilian government feared the FEB would capitalize politically on its contributions to the Allied victory, however modest, and officially demobilized it as soon as the war ended, while it was still in Italy.[34]

Restrictions were imposed on its members upon their return to the country, non-military veterans (who were discharged upon their return) were forbidden to wear decorations or expeditionary garments in public, while professional (military veterans) were transferred to frontier regions or far from major centers.[35]

FEB Veterans Association

From October 1945 on, the first Ex-Combatants Associations were formed. The non-planning by the Brazilian military authorities of the time, regarding a policy of assistance and social reintegration of its veterans, especially the vast majority of civilians without high professional qualifications, collaborated to the growth of such associations. From the disengagement of this objective from the public agency that had been created for the purpose (the Brazilian Legion of Assistance), they began to function as the only point of social support for veterans.[36]

Between 1946 and 1950, there was a political dispute between communist and conservative veteran groups for leadership in the associations, which revolved around whether the associations should seek greater participation in national politics or stick to the immediate claims of veterans. It was won by the conservatives, with the support of the military leadership of the time, anticipating certain practices that would become standard in discussions of internal issues in the Army and other Armed Forces in the 1950s-1960s.[34]

A pension for surviving veterans was established in 1988, with the 1988 Constituent Assembly, when all surviving Brazilian veterans of the Second World War became legally entitled to a special compensation, equivalent to the pension left by a second lieutenant in the army.[37] This benefit not only extended to veterans who had not been in the Italian or Atlantic campaigns but did not differentiate between them and those who had served in continental Brazil during the war. The debate that preceded it, added to resentments accumulated over four decades, also served to increase the already existing feud between veterans who had active participation in the aforementioned campaigns and those who did not.[38]

In the time between the end of the war and the granting of this pension, the veterans achieved small victories, such as access to the civil service for those who were not literate (which excluded a considerable number of veterans), and the construction of a Housing Complex for ex-combatants (in the Benfica neighborhood), in Rio de Janeiro, inaugurated at the beginning of the 1960s.[39] Those who could not readapt to civilian life often became dependent on the associations.[34][38]

See also

Notes

- ↑ There is no consensus as to the exact number of ships attacked. Some sources include certain events and rule out others. For example, the website "Poder Naval" lists 38 ships. The sinking of the Taubaté and the Shangri-lá are not included. However, it mentions the sinking of two unidentified ships, one in June 1942, by the U-159, and another in August 1942, by the U-507, as well as the sinking of the White Swan, whose torpedoing was not officially confirmed, as well as the corvette Camaquã and the cruiser Bahia, which sank for reasons other than acts of war. The World War II portal mentions 39 events, including the Shangri-lá, two unidentified ships, the corvette Camaquã, and the Bahia, leaving out the Taubaté. In some sources, Commander Lira is also not mentioned, likely because the ship was not sunk. Roberto Sander, in his book O Brasil na mira de Hitler lists 34 ships, leaving out the Paracuri.

- ↑ In September 1942, the private companies Cia. de Navegação Costeira and Lloyd Nacional - both owned by the same owner - were taken over by the government and incorporated into the assets of the state-owned Lloyd Brasileiro.

- ↑ They were: Cia. Carbonífera Sul-Riogandense; Cia. de Cabotagem de Pernambuco and Cia. Serras de Navegação.

- ↑ France at the time, was under the Vichy regime).

- ↑ Brazil did not declare war on Japan, because it understood that Japan was not responsible for any sinking of Brazilian ships.

- ↑ The U-507, due to the actions it performed off the coast of Brazil, was one of the most studied German submarines in Brazilian naval historiography, and it is unlikely that another sinking besides the six already mentioned could go unnoticed by researchers and historians.

References

- 1 2 3 Seitenfus, Ricardo (2000). A Entrada do Brasil na Segunda Guerra Mundial (in Portuguese). EDIPUCRS. pp. 314–317.

- ↑ Cytrynowicz, Roney (2000). "A batalha da produção". Guerra sem guerra (in Portuguese). EDUSP. ISBN 8586028959.

- 1 2 Brayner, Floriano de Lima (1968). A verdade sobre a FEB: Memórias de um chefe de Estado-Maior na Campanha da Itália, 1943-45 (in Portuguese). Civilização Brasileira.

- 1 2 Silva, Hélio (1972). 1942 Guerra no Continente, Civilização Brasileira.

- ↑ Sander (2007).

- ↑ Costa, Sérgio Correa da (2004). Crônica de uma Guerra Secreta (in Portuguese). Record. ISBN 85-01-07031-9.

- ↑ "EUA planejavam tomar o País caso Getúlio não entrasse na guerra contra os nazistas". ISTOÉ (in Portuguese). 8 August 2001. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "O Pentágono quis invadir o Brasil. Entrevista de Luiz Alberto de Vianna Moniz Bandeira para a DW-World". DW-World (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Perdas Navais brasileiras na 2ª Guerra Mundial". Poder Naval (in Portuguese). 4 October 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bonalume Neto, Ricardo. "Ofensiva submarina alemã contra o Brasil". Grandes Guerras. Artigos do Front. (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 de Ferrari, Marcello. "Submarinos alemães naufragados no Brasil". Naufrágios (in Portuguese). Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Sander (2007, pp. 54, 55).

- 1 2 "Marinha Brasileira na Segunda Guerra Mundial". Defesa BR (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elísio, Gomes Filho. "O U-507, o algoz da Marinha Mercante brasileira". Naufrágios do Brasil (in Portuguese). Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vilela, Túlio. "Brasil na Segunda Guerra. Terror no Atlântico". UOL Educação (in Portuguese). Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ↑ Dias da Cunha, Rudinei. "Navios brasileiros atacados por forças da Alemanha e Itália. 1941-1945". História da Força Aérea Brasileira. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Mapa de navios brasileiros afundados". Portal da Segunda Guerra Mundial (in Portuguese). Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Figueiredo Moreira, Pedro Paulo (1942). "Um relato de um sobrevivente do ataque ao Itagiba". Itagiba (in Portuguese). Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ↑ ""SS Santa Clara"". Wrecksite. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ↑ "Suloide". Wrecksite. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- 1 2 Bertonha, João Fábio (1997). "O Brasil, os imigrantes italianos e a política externa fascista, 1922-1943" (PDF). Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional. 40 (2): 106–130. doi:10.1590/S0034-73291997000200005.

- 1 2 Bertonha, João Fábio (2007). "Divulgando o Duce e o fascismo em terra brasileira: a propaganda italiana no brasil, 1922-1943". Revista de História Regional.

- ↑ Fonseca, Celso (24 November 2000). "Gargantas Cortadas". IstoÉ Online. No. 1626. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ↑ "A Marinha Mercante atuando na Segunda Grande Guerra". Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Gama, Arthur Oscar Saldanha (1982). A Marinha do Brasil na Segunda Guerra Mundial (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: CAPEMI Editora.

- ↑ Revista Marítima Brasileira - Year LXX1 - Oct./Dec. 1951. Rio de Janeiro, Naval Press, Ministry of Navy, 1952.

- ↑ "DECRETO Nº 10.358, DE 31 DE AGOSTO DE 1942". planalto.gov.br. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilten (22 April 2011). "22 de abril, Dia da Aviação de Caça". Página do Poder Áereo (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sander (2007, pp. 218–2019).

- ↑ "O batismo de fogo da FAB completa 73 anos" (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Além do U-507, outros 10 submarinos do Eixo foram afundados no Brasil" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2021-11-01. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ↑ "UNH". Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ "País foi chamado a ocupar a Áustria". Estadão (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 Castro, Celso; Izecksohn, Vitor; Kraay, Hendrik (2004). Nova história militar brasileira (in Portuguese). Fundação Getúlio Vargas. ISBN 85-225-0496-2.

- ↑ Depoimento de oficiais da reserva sobre a FEB. Editora Cobraci. 1949.

- ↑ Celso, Castro; Izecksohn, Vitor; Kraay, Hendrik (2004). "Os veteranos da FEB e a sociedade brasileira". Nova história militar brasileira (in Portuguese). Fundação Getúlio Vargas. ISBN 85-225-0496-2.

- ↑ Motta, Aricildes de Moraes (2001). História oral do Exército na segunda guerra mundial (in Portuguese). p. 296.

- 1 2 Soares, Leonércio (1985). Verdades e vergonhas da Força Expedicionária Brasileira (in Portuguese). p. 339.

- ↑ Castro, Erik de. "A Cobra Fumou". Documentary, 2002. Production: BSB Cinema, Limite Produções and Raccord Produções. Director: Vinícius Reis. Running time: 92 min.

Bibliography

- Sander, Roberto (2007). O Brasil na mira de Hitler: a história do afundamento de navios brasileiros pelos nazistas (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva.

Further reading

- Bonalume Neto, Ricardo (1995). A Nossa Segunda Guerra: Os brasileiros em combate (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Expressão e Cultura.

- Monteiro, Marcelo (2012). U-507 - O submarino que afundou o Brasil na Segunda Guerra Mundial (in Portuguese). Salto: Schoba.

.jpg.webp)