"The Olimpico" | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Former names | Stadio dei Cipressi (1928-53) Stadio dei Centomila (1953-60) |

|---|---|

| Location | Viale dello Stadio Olimpico, I-00135 Rome |

| Coordinates | 41°56′02″N 12°27′17″E / 41.93389°N 12.45472°E |

| Owner | Sport e Salute.[1][2] |

| Operator | Italian National Olympic Committee |

| Capacity | 70,634[3] |

| Field size | 105 × 68 m |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1927 |

| Built | 1937-38, 1951-53 |

| Opened | 17 May 1953[4] |

| Expanded | 1989-90, 2007-08 |

| Construction cost | 3,400,000,000 ITL (1953) 233,000,000,000 ITL (1989-90) 17,000,000 € (2007-08) |

| Architect | E. Del Debbio (1928) L. Moretti (1933-37) C. Valle (1951) A. Vitellozzi (1951-53, 1988-90) M. Clerici (1988-90) |

| Builder | Speroni (1927) Cogefar (1988-90) |

| Structural engineer | A. Frisa, A. Pintonello (1927) C. Roccatelli (1951-53) P. Teresi, A,M. Michetti, M. Majowiecki (1988-90) |

| Tenants | |

| S.S. Lazio (1953–present) A.S. Roma (1953–present) Italy national football team (1953-present) Italy national rugby union team (1954-present) | |

Stadio Olimpico (English: Olympic Stadium) is an Italian multi-purpose sports venue located in Rome. It is the largest sports facility of the city and the second-largest of Italy - after Milan's Meazza Stadium - seating more than 70,600 spectators.[3] In the past it used to host up to one hundred thousand people and for this reason was also called Stadio dei Centomila (Stadium of the 100,000). It is also called colloquially l'Olimpico (The Olympic).

It stands in the plans between the bottom of Monte Mario and the river Tiber, in the northwestern sector of the city. It is part of the architectural complex known as Foro Italico, which construction started in 1928 under the supervision of the architect Enrico Del Debbio (also designer of the original structure of the stadium). Though still unfinished, it was officially opened in 1932 as Stadio dei Cipressi (Stadium of the Cypresses) then, in 1937, it was expanded by the architect Luigi Moretti to whom the Fascist regime commissioned the realization of a sports venue which celebrated the virtues of the Italian youth. The Second World War interrupted further extensions; after the Liberation of Rome in June 1944, the stadium was used by the Allies as vehicle storage and also as seat of Anglo-American military competitions.

After the WWII, the Italian National Olympic Committee (CONI) was appointed as operator of the venue; CONI entrusted the architets Cesare Valle, Carlo Roccatelli and, after the death of the latter, Annibale Vitellozzi, of the building of a suitable sports venue. Between 1951 and 1953 the new stadium was built; its official opening took place on 17 May 1953 with an association football match between Hungary and Italy and the finish of a stage of the Giro d'Italia. One week later, it became the venue of the city's two principal professional football clubs, S.S. Lazio and A.S. Roma.

In 1954 it also hosted the grand final of the rugby union European Cup between Italy and France. At that time, the stadium was known as Stadio dei Centomila; its name changed once Rome was handed in 1955 the organization of the 17th Summer Olympics to take place in 1960.

At the time of its opening and for the following 37 years, no stand of the Olimpico was covered except for the Tribuna Monte Mario (Monte Mario Grand Stand): the venue was almost entirely rebuilt between 1988 and 1990 for the 1990 FIFA World Cup of which Italy was host country, and every sector of it was covered.

With regard to international association football, the Olimpico was amongst the venues which hosted the 1968 and 1980 European Championships and the 1990 FIFA World Cup and where the final of the said tournaments took place. More recently, hosted a group and one of the quarter-finals of the 2020 European Championship and is also amongst the potential venues for the 2032 European Championship.

With regard to club football, instead, the venue hosted two finals of the European Cup, in 1977 and 1984, and two of the renewed UEFA Champions' League in 1996 and 2009. It also acted as neutral venue of the 1973 Intercontinental Cup between Juventus FC and the Argentine side CA Independiente and as home venue of AS Roma in the 2nd leg of the 1991 UEFA Cup final against Inter FC. In 1964 it also exceptionally hosted the only tie-breaker (as to 2023) to decide the champion side of the season, having Inter and Bologna finished the league level on points. Since 2008 the Olimpico regularly hosts the Coppa Italia final with the exception of 2020.

With regard to other sports, the Olimpico hosted the opening and closing ceremonies of the aforementioned 1960 Olympics together with its track-and-field events, the 1974 European Athletics Championships, the 1987 World Championships in Athletics and the 1975 Universiade. In 2024 it will host the European Athletics Championships for the second time. Since 1980 is a regular host of the Golden Gala.

In 1954 the Olimpico hosted its first international rugby union match; more recently, since 2012 is the venue of the home matches of Italy in the Six Nations. After its 1990 renewal the stadium is also a concerts venue: the record attendance for a single musical event was set in 1998 when 90,000 spectators (of whom 82,000 paying audience) attended a concert of Claudio Baglioni.[5][6]

For most part of its life the Olimpico, together with the Foro Italico, was a State-owned estate. In 2004 its property was transferred to Coni Servizi, a sports venues management government agency[1] which later changed its name in Sport e Salute,[2] whereas the operator of the venue is the Italian National Olympic Committee.

History

Stadio dei Cipressi

In the 1909 city planning designed by the architect Edmondo Sanjust there were no sports venues planned in the nortwestern sector of Rome.[7] The Fascist regime, which saw sport as an effective propaganda vector, in 1926 imposed changes to the urbanistic plan to include an area where to build an huge sports complex.[8] The 85-hectars area was basically a swamp at the bottom of Monte Mario, on the right bank of the river Tiber,[9] in the nascent quarter Della Vittoria.[8]

The Foro Italico sports complex was commissioned by Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB), a youth organisation established by the Fascist government; the building works started in 1928 under the supervision of the architect Enrico Del Debbio,[8][10] and the Stadio dei Cipressi was amongst the venues partially completed in time to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the rise of Fascism in Italy (22 October 1922). The new stadium was opened to the public on 22 October 1932, though still unable to host the 100,000 planned spectators. Its main terrace leaned on the slope of Monte Mario; since the ground was marshy due to the rainwater that came down from the slopes of the hill, to create the playing field the ground was raised by 4 metres using the 2 million cubic meters of soil excavated for the foundations.[11] The facility was more suitable for large gatherings than for sporting competitions, since its pitch's surface was about 20,000 square metres (approx. 200 m length × 100 width).[11]

The official opening took place the following 4 November, on the 14th anniversary of the Italian victory in World War I, with a gymnastics exhibition organized by the youth's Fascist associations.[9]

Since the regime intended to apply for the organization of the 1940 Summer Olympics (which eventually never took place),[11] starting from the 1933 the Stadio dei Cipressi was subjected to extensions which project was entrusted to Luigi Moretti, Angelo Frisa and the engineer Achille Pintonello,[12] who designed a concrete structure[12] which hosted a main football pitch and secondary pitches for basketball and weightlifting.[13] The renewed stadium was opened on 9 May 1937, 1st anniversary of the Italian Empire. At that time the Stadio dei Cipressi might host no more than 60,000 spectators, but there was already a project to raise that capacity up to 100,000.[13] After the adsorption of the ONB by GIL (Gioventù Italiana del Littorio, National Fascist Party's youth branch), the latter became owner of the stadium and of the rest of the sports complex.

In spite of being a multisports venue, Stadio dei Cipressi was never used differently than a place for military exhibitions and mass gatherings: in 1938 it hosted a parade to welcome the German dictator Adolf Hitler during his state visit in Rome[14] and, later, to host a gymnastics exhibition organized by GIL[15]

During the Second World War, in September 1941 the stadium hosted a military celebration of the Tripartite Pact, the political / military alliance between Italy, Germany and Japan.[16]

Any planned extension of the stadium was interrupted with the arrival of the war in Rome in 1943 and the following fall of Fascism; when in 1944 the Anglo-American forces entered in Rome the stadium was used by the Allied troops as vehicle storage and as venue for military sports events.[17]

Stadio dei Centomila

After the war, the Italian National Olympic Committee (CONI) was appointed as operator of the stadium.[18] CONI chairman Giulio Onesti announced that the renewal works would end in 1950.[18]

The renewal project was entrusted to engineer Carlo Roccatelli and to architect Cesare Valle, at that time both members of the Superior Council of Public Works.[19]

The management of the stadium by CONI was complicated by a complex bureaucratic matter: after the fall of the Fascism, the Badoglio government abolished the existing Fascist organizations and reassigned all their estates to a newly established agency named Commissariato della Gioventù Italiana (Commission for the Italian Youth), with the provision that after the end of the war and the return to normal administration the Commission would fold after the assignment of the estates either to the Defence Office or the Education Department according to their nature and purpose.[20] Nonetheless, the Commission was never discontinued and it retained the ownership of the Foro Italico, included the stadium.[20]

The matter was the subject of a fierce political battle: the Communist Party, through its house organ, the newspaper l'Unità, accused the governance of the Commission, led by Giovanni Valente - a member of Christian Democracy politically close to Amintore Fanfani - of misuse of the complex to establish a sports organization parallel to CONI, meant to favour the sports clubs close to Azione Cattolica, a lay Catholic association.[21][22] Later in the decade l'Unità accused Valente to have mortgaged the complex for three billion lire (approx. 1,500,000 €) to finance the project of ENAL (a statutory corporation of assistence to working people of which Valente itself was director) to establish a parallel betting pool alternative to Totocalcio (organized by CONI).[23] The complex affair found a solution in 1976 when the Commission was finally suppressed[24] and all its estates were picked up by the State.[25]

Annibale Vitellozzi replaced Roccatelli in 1951 after the latter's death[12] and finished the stadium in 1953 at a cost of 3,400,000,000 lire (approx 1,700,000 €).[26]

The new stadium was a 33,500 square metres[26] concrete structure clad with travertine.[12] It was composed by two parallel stands of equal lenght (approx. 140 metres), the Tribuna Tevere on the eastern side and Monte Mario on the western side,[12]; the nothern and souther stands were shaped as two hemicycles of 95 metres radius.[12] The athletics track was 507 metres long.[26][12] The stadium was 319 metres long and 189 wide.[12] Its height from the pitch to the top was about 18 metres, howewer the structure was only 13 metres high above the ground level, being the pitch about 4.5 metres below it.[12] The latter solution was adopted to prevent the stadium from overwhelming the panorama of the complex and match it in consistent way with the rest of the other buildings of the Foro Italico complex.[12]

The attendance could access through 10 gates (two per each hemycicle stand and three for each straight stand); the whole stadium was unroofed except for the Monte Mario Grand Stand,[26] atop of which was realised an iron structure 80 metres long composed by 40 cubicles 2-metres long each for the radio and TV commentators.[26] In the said grandstand was also created a press room equipped with 54 phone boots plus teletype, wirephoto and telegraph.[26] 572 seats (of which 276 roofed) were reserved for the press.[26]

The Stadio dei Centomila (Stadium of the 100,000 because of its highest expected capacity) was officially opened on 17 May 1953 by the then President of Italy Luigi Einaudi.[27] The sports events which took place that day were the International Cup's football match between Italy and Hungary then the finish of the sixth stage (from Naples to Rome) of the Giro d'Italia. Hungary won 3-0 with a goal by Nándor Hidegkuti - first ever scorer in the stadium - and a double of Ferenc Puskás.[28] After the match the crowd attended the finish of the cycling race, won by Giuseppe Minardi.[29]

The following Sunday the stadium hosted its first ever club football match, the game of the 35th matchday of 1952-53 Serie A between SS Lazio and Juventus FC, won 1-0 by the latter with a goal from Pasquale Vivolo.[30] In the following matchday, the final one of the league, also AS Roma debuted in the new stadium with a draw 0-0 against SPAL.[31] Since then the Olimpico is the home venue of both clubs.

In 1954 Italy hosted the fifth rugby union European Cup, and the Stadio dei Centomila was appointed as venue for its final which took place between Italy and France; in front of an estimated crowd of about 25,000 attendees France won 39-12.[32][33]

The 1960 Olympics

In 1955 the International Olympic Committee appointed Rome as host city of the 17th Summer Olympics which would be held in 1960.[34] That appointment made more urgent the completion of some works to make the stadium - which name "Dei Centomila" was being slowly replaced by "Olimpico" - compliant for the event. Works were relatively minimal, having been the stadium built recently: the seats for the press were raised from 572 to 1,126,[26] and four lighting towers were put in place for evening events providing illumination amounting to 250 lx.[26] Further, two electronic scoreboards were installed atop of the northern and southern stands; they started to operate on 18 October 1959 on the occasion of a league derby won 3-0 by AS Roma.[35] The stadium was also provided with an autonomous power plant able to produce 375,000 watts.[26]

On 25 August 1960 the stadium hosted the opening ceremony of the 17th Summer Olympics.[36] Amongst the feats that took place in the stadium during the Games, there were the three gold medals of the American sprinter Wilma Rudolph, in the 100 metres (with the world record),[37] in the 200 metres[38] (with the world record in the semifinal heat)[38] and in the 4×100 relay (also with world record) together with her teammmates Martha Hudson, Lucinda Williams and Barbara Jones.[39]

Other remarkable performances in track-and-field were the gold medal with the world record in the 400 metres by the American Otis Davis and the victory in the 1500 metres by the Australian Herb Elliott;[40] also the gold medal of the Unified German Team in the men's 4×100 relay (Bernd Cullmann, Armin Hary, Walter Mahlendorf and Martin Lauer) and eventually the Soviet gold by Lyudmila Shevtsova, whom on the occasion equalled the record she already held.[39]

The post-Olympics

After the Games the Olimpico kept on being used primarily as association football venue. Aside from hosting the home games of SS Lazio and AS Roma, the stadium was appointed as seat of the first ever (and, to date, only) play-off for the Scudetto in 1963-64: in that season Bologna FC and FC Inter had ended the Italian League level on points and a tie-breaker was needed to assign the title. Bologna won their 7th (and, to date, latest) Scudetto beating Inter 2-0 with an own goal of Giacinto Facchetti and a goal by Harald Nielsen.[41]

In 1960 UEFA established the European Championship which final tournament's host would be chosen amongst one of the four countries that reached the semi-finals. Italy wasn't able to reach that stage in the first two editions but in 1968 it joined the Final Four together with England, Yugoslavia and the U.S.S.R., and was appointed by UEFA to host the final tournament[42]. Whereas Florence and Naples hosted the semi-finals, the Olimpico was appointed as seat of the title game, which saw the home team facing Yugoslavia. For the first (and to date only) time in the history of the tournament, was necessary a replay: on 8 June 1968 the match, indeed, ended 1-1 with a goal of Dragan Džajić equalled in the last minutes by the Italian Angelo Domenghini.[43] Two days later, Italy beat Yugoslavia 2-0 with one goal each by Luigi Riva and Pietro Anastasi and were crowned European champion.[44]

In 1973 Juventus FC, runner-up of 1972–73 European Cup, was invited to represent UEFA in the Intercontinental Cup against the Argentine CA Independiente, upon refusal of the European champions AFC Ajax to take part to the Cup.[45] Since both teams' schedules were busy to arrange a 2-leg match, the Italian football federation suggested to play a one-off game in the Olimpico as neutral venue, a solution on which both clubs agreed.[46]

On 28 November 1973, in front to an attendance of 22,000, Independiente won 1-0 with a goal by Ricardo Bochini.[47]

In 1974 the stadium was the seat of the 11th European Athletics Championships, which witnessed the rise of two world-class Italian athletes, the sprinter Pietro Mennea and the high-jumper Sara Simeoni, respectively winner of the 200 metres[48] and runner-up in the 100 metres[49] and the 4×100 relay[50], and bronze in the high-jump with 1.89 metres.[50]

Another relevant event for which the Olimpico was chosen were the 8th University Games,[51] originally assigned to Belgrade that was, however, unable to hold the Games because of financial issues that hit Yugoslavia in late 1974.[52] Since there was no time for organizing a complete multisports event, the edition held in Rome featured only the track-and-field games, and again Pietro Mennea was amongst the leading athletes by winning both the 100[53] and the 200 metres,[54] while in the long-distance running stood out Franco Fava, winer of the 5000[54] and the 10000 metres.[55]

In 1977 Rome got to host for the first time the final of the European Cup, which was to be held between Borussia Mönchengladbach and Liverpool FC, both seeking for their first ever title[56]. The Cup went to the English side who won 3-1 thanks to one goal each by Terry McDermott, Tommy Smith and Phil Neal whereas the Danish Allan Simonsen scored the temporary equaliser for the German team. At the Olimpico Liverpool became the 2nd English and the 3rd British overall side to be crowned European champion.[57]

The 1980 edition of the European Championship was a 8-team final tournament which host was appointed by UEFA before the start of the qualifying round. The first country appointed to host the renewed competition was Italy[58][59]. The Olimpico hosted the opening ceremony of the competition, which featured also an exhibition of Calcio storico fiorentino, a Medieval form of association football played in Florence,[60] to which followed the inaugural game between the incumbent European champions Czechoslovakia and West Germany, won 1-0 by the latter with a goal by Karl-Heinz Rummenigge.[61] Again Czekoslovakia featured in the stadium during the group stage, with a win 3-1 over Greece;[62] the third and last game hosted in the Olimpico was the Championship final, held on 22 June 1980 where Belgium faced West Germany, which achieved the title by winning the match 2-1 with a double by Horst Hrubesch which made vain the single goal of the Belgian René Vandereycken.[63]

1990 restructuring and roofing of the stadium

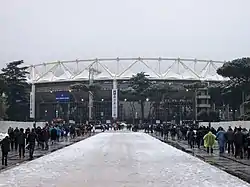

.jpg.webp)

For the 1990 FIFA World Cup, for which it was the main stadium, the facility underwent an extensive renovation. While that work was underway in 1989 the Capitoline teams Lazio and Roma had to play their Serie A games at Stadio Flaminio. The work was entrusted to a team of designers including the original architect Annibale Vitellozzi. From 1987 to 1990, the construction plan was amended several times, with a consequent rise in costs. Ultimately, the Olimpico was entirely demolished and rebuilt in reinforced concrete, with the exception of the Tribuna Tevere which was expanded with the addition of further steps and of the curves which were closer to the field by nine metres. All sectors of the stadium were provided with full coverage in tensostructure white. Backless seats in blue plastic were installed and two giant screens built in 1987 for the World Athletics Championships were also mounted inside the curve. In the end the new version of the Olimpico had 82,911 seats. It was the 14th stadium in the world for number of seats among the football stadiums, the 29th among all stadiums and the second in Italy, just behind the San Siro Stadium of Milan.

The Stadio Olimpico hosted five matches that the Italy national team took part and the final between West Germany and Argentina. West Germany won the final match 1–0.

With the same layout from 1990, the Stadio Olimpico hosted on 22 May 1996 the UEFA Champions League Final between Juventus and Ajax which saw the Bianconeri prevail in a penalty shoot-out.

2008 restyling of the stadium

.jpg.webp)

In 2007, a vast plan of restyling the internal design of the stadium was laid out, to conform to UEFA standards for the 2009 UEFA Champions League Final which was held in Rome. The work was performed and completed in 2008. It included the establishment of standard structures with improvements in security, the fixing of dressing rooms and of the press room. It also included the replacement of all seats, the installation of high definition LED screens, the partial removal of plexiglas fences between spectators and the field and a reduction of seating to the current capacity of 70,634. In order to enhance the comfort of the audience, part of the modernisation of the stadium involved increasing the number of restrooms and fixing the toilets. As a result of these improvements, the Stadio Olimpico was classified a UEFA Elite stadium.

.jpg.webp)

Areas and capacity

The stadium has a current capacity of 72,698, distributed as follows:[64]

- Tribuna Monte Mario – 16,555

- Tribuna Tevere – 16,397

- Distinti Sud Ovest – 5,747

- Distinti Sud Est – 5,637

- Distinti Nord Ovest – 5,769

- Distinti Nord Est – 5,597

- Curva Sud – 8,486

- Curva Nord – 8,520

- For end stage concerts/shows it can hold up to 75,000.

- For center stage concerts/shows it can hold up to 78,000.

Competitions hosted

- 1960 Summer Olympics

- UEFA Euro 1968

- 1974 European Athletics Championships

- 1975 Summer Universiade

- 1977 European Cup Final

- UEFA Euro 1980

- 1984 European Cup Final

- 1987 World Championships in Athletics

- 1990 FIFA World Cup

- 1996 UEFA Champions League Final

- 2001 Summer Deaflympics

- 2009 UEFA Champions League Final

- UEFA Euro 2020

- 2024 European Athletics Championships

Famous matches

- The 1968 European Championship final match saw Italy win against Yugoslavia 2–0.

- The 1973 Intercontinental Cup match saw Independiente win the trophy against Juventus 1-0

- The 1977 European Cup Final match saw Liverpool win the trophy against Borussia Mönchengladbach 3–1.

- The 1980 European Championship final match saw Germany win against Belgium 2–1.

- The 1984 European Cup Final match saw Liverpool win the trophy after a penalty shootout against native team Roma (regular time ended 1–1).

- The 1990 FIFA World Cup Final match saw West Germany win against Argentina 1–0.

- The 1996 UEFA Champions League Final saw Juventus win the trophy after a penalty shootout against Ajax (regular time ended 1–1).

- The 2009 UEFA Champions League Final saw Barcelona win against Manchester United 2–0.

- The 2013 Six Nations Championship saw the Italian rugby team beat France for only the second time in the championship and the first time at this stadium.

- The 2013 Six Nations Championship saw the Italian rugby team beat Ireland for the first time ever in the championship.

Average attendances

The average season attendance at league matches held at the Stadio Olimpico for Lazio and Roma.[65]

|

|

|

# In 1989–90 season both teams played at Stadio Flaminio during the renovations of Stadio Olimpico.

*Club was in Serie B

![]() = Serie A champions

= Serie A champions

![]() = Coppa Italia winners

= Coppa Italia winners

Notable international football matches

UEFA Euro 1968

The stadium was one of the venues of the UEFA Euro 1968, and held three matches.

| Date | Time (UTC+02) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 June 1968 | 15:00 | 2–0 | Third place play-off | 68,817 | ||

| 21:15 | 1–1 (a.e.t.) | Final | 68,817 | |||

| 10 June 1968 | 21:15 | 2–0 | Final replay | 32,886 |

UEFA Euro 1980

The stadium was one of the venues of the UEFA Euro 1980, and held four matches.

| Date | Time (UTC+02) | Team #1 | Res. | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 June 1980 | 17:45 | 0–1 | Group 1 | 10,500 | ||

| 14 June 1980 | 20:30 | 1–3 | 7,614 | |||

| 18 June 1980 | 20:30 | 0–0 | Group 2 | 42,318 | ||

| 22 June 1980 | 20:30 | 1–2 | Final | 47,860 |

1990 FIFA World Cup

The stadium was one of the venues of the 1990 FIFA World Cup, and held six matches.

| Date | Time (UTC+02) | Team #1 | Result | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 June 1990 | 21:00 | 1–0 | Group A | 73,303 | ||

| 14 June 1990 | 1–0 | 73,423 | ||||

| 19 June 1990 | 2–0 | 73,303 | ||||

| 25 June 1990 | 2–0 | Round of 16 | 73,303 | |||

| 30 June 1990 | 0–1 | Quarter-finals | 73,303 | |||

| 8 July 1990 | 20:00 | 1–0 | Final | 73,603 |

UEFA Euro 2020

The stadium was one of the venues of the UEFA Euro 2020, and hosted four matches.

| Date | Time (UTC+02) | Team #1 | Result | Team #2 | Round | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 June 2021 | 21:00 | 0–3 | Group A | 12,916[66] | ||

| 16 June 2021 | 3–0 | 12,445[67] | ||||

| 20 June 2021 | 18:00 | 1–0 | 11,541[68] | |||

| 3 July 2021 | 21:00 | 0–4 | Quarter-finals | 11,880[69] |

Concerts

| Date | Performer(s) | Opening act(s) | Tour/Event | Attendance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 June 1992 | Amedeo Minghi | 25.000 | |||

| 8 July 1992 | Elton John | The One Tour | |||

| 16 June 1993 | Zucchero | L'urlo Tour 1992/1993 | |||

| 9 July 1993 | Pino Daniele | ||||

| 28 July 1993 | Litfiba | Terremoto Tour | |||

| 16 June 1994 | Pino Daniele, Eros Ramazzotti and Jovanotti | ||||

| 7 September 1995 | Antonello Venditti | ||||

| 22 September 1995 | Pino Daniele | Non calpestare i fiori nel deserto Tour | |||

| 4 October 1995 | Renato Zero | ||||

| 7 October 1995 | Antonello Venditti | ||||

| 9 October 1995 | |||||

| 30 October 1995 | Renato Zero | ||||

| 8 June 1996 | Ligabue | Buon compleanno Elvis Tour | |||

| 27 June 1996 | Vasco Rossi | Nessun pericolo per te Tour | |||

| 5 July 1996 | Santana | Phish | 1996 Tour | ||

| 7 July 1996 | Tina Turner | Wildest Dreams Tour | |||

| 9 July 1996 | Various artists | Live Link Festival | |||

| 10 July 1996 | |||||

| 26 September 1996 | Eros Ramazzotti | Dove c'è musica Tour | |||

| 5 July 1997 | Ligabue | Il Bar Mario è aperto Tour | |||

| 6 July 1997 | Negrita | ||||

| 5 September 1997 | Jovanotti | ||||

| 6 June 1998 | Claudio Baglioni | ||||

| 7 June 1998 | |||||

| 12 June 1998 | Eros Ramazzotti | ||||

| 11 June 1999 | Renato Zero | ||||

| 12 June 1999 | |||||

| 13 June 1999 | |||||

| 19 June 1999 | |||||

| 23 June 1999 | Vasco Rossi | Rewind Tour 1999 | |||

| 24 June 1999 | |||||

| 29 June 1999 | Backstreet Boys | Into the Millennium Tour | |||

| 8 October 1999 | Antonello Venditti | ||||

| 10 July 2000 | Ligabue | 10 anni sulla mia strada Tour | |||

| 4 July 2001 | Vasco Rossi | Stupido hotel Tour 2001 | |||

| 7 July 2001 | Sting | Brand New Day Tour | |||

| 4 July 2002 | Renato Zero | ||||

| 15 July 2002 | Ligabue | Fuori come va Tour | |||

| 23 July 2002 | The Cure | Tour 2002 | 15,000 | ||

| 25 June 2003 | Carmen Consoli | ||||

| 1 July 2003 | Claudio Baglioni | ||||

| 5 June 2004 | Vasco Rossi | Buoni o cattivi Tour 2004 | |||

| 24 June 2004 | Renato Zero | ||||

| 7 July 2004 | Eros Ramazzotti | ||||

| 5 June 2005 | Nomadi | ||||

| 10 June 2005 | R.E.M. | Around the Sun Tour | |||

| 23 July 2005 | U2 | Ash, Feeder | Vertigo Tour | 67,002 | |

| 3 June 2006 | Ligabue | Velvet, Tiromancino | Nome e cognome Tour | ||

| 16 June 2006 | Roger Waters | The Dark Side of the Moon Live | 13,906 | ||

| 17 July 2006 | Depeche Mode | Scarling., Franz Ferdinand | Touring the Angel | 40,000 | The concert was recorded for the group's live albums project Recording the Angel. |

| 6 August 2006 | Madonna | Paul Oakenfold | Confessions Tour | 63,054 | |

| 3 June 2007 | Renato Zero | ||||

| 20 June 2007 | Iron Maiden | Motörhead Machine Head Mastodon Lauren Harris Sadist |

A Matter of the Beast Tour | ||

| 27 June 2007 | Vasco Rossi | Vasco Live 2007 | |||

| 28 June 2007 | |||||

| 6 July 2007 | The Rolling Stones | Biffy Clyro | A Bigger Bang | 40,000 | |

| 21 July 2007 | George Michael | 25 Live | |||

| 29 May 2008 | Vasco Rossi | Il mondo che vorrei live Tour 2008 | |||

| 30 May 2008 | |||||

| 18 July 2008 | Ligabue | Elle-Elle Live 2008 | |||

| 6 September 2008 | Madonna | Benny Benassi | Sticky & Sweet Tour | 57,690 | |

| 16 June 2009 | Depeche Mode | M83 | Tour of the Universe | 44,070 | The concert was recorded for the group's live albums project Recording the Universe. |

| 24 June 2009 | Tiziano Ferro | Alla mia età Tour | 20,000 | ||

| 19 July 2009 | Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band | Working on a Dream Tour | 37,834 | ||

| 9 July 2010 | Ligabue | Stadi 2010 | |||

| 10 July 2010 | |||||

| 8 October 2010 | U2 | Interpol | U2 360° Tour | 75,847 | The performance of Bad was recorded for the group's live album U22: A 22 Track Live Collection from U2360°. |

| 1 July 2011 | Vasco Rossi | Vasco Live Kom '011 | |||

| 2 July 2011 | |||||

| 9 July 2011 | Jovanotti | ||||

| 12 June 2012 | Madonna | Martin Solveig | The MDNA Tour | 36,658 | |

| 28 June 2012 | Various artists | soundRome 2012 | |||

| 14 July 2012 | Tiziano Ferro | ||||

| 21 June 2013 | Eros Ramazzotti | Noi World Tour | |||

| 28 June 2013 | Jovanotti | Backup Tour | |||

| 6 July 2013 | Muse | Arcane Roots, We Are the Ocean | The 2nd Law World Tour | 60,963 | The concert was filmed and recorded for the group's concert film and live album Live at Rome Olympic Stadium. |

| 16 July 2013 | Negramaro | ||||

| 20 July 2013 | Depeche Mode | Motel Connection, Matthew Dear | The Delta Machine Tour | 56,007 | |

| 28 July 2013 | Roger Waters | The Wall Live | 50,848 | ||

| 30 May 2014 | Ligabue | Mondovisione Tour | |||

| 31 May 2014 | |||||

| 23 June 2014 | Vasco Rossi | Vasco Live Kom '014 | |||

| 25 June 2014 | |||||

| 26 June 2014 | |||||

| 30 June 2014 | |||||

| 11 July 2014 | Modà | ||||

| 26 June 2015 | Tiziano Ferro | Lo Stadio Tour 2015 | |||

| 27 June 2015 | |||||

| 12 July 2015 | Jovanotti | Lorenzo negli stadi 2015 | |||

| 5 September 2015 | Antonello Venditti | Tortuga II Tour | |||

| 11 June 2016 | Laura Pausini | Simili Tour | |||

| 15 June 2016 | Pooh | ||||

| 22 June 2016 | Vasco Rossi | Live Kom 2016 | |||

| 23 June 2016 | |||||

| 24 June 2016 | |||||

| 26 June 2016 | |||||

| 25 June 2017 | Depeche Mode | Algiers | Global Spirit Tour | 51,845 | |

| 28 June 2017 | Tiziano Ferro | Il mestiere della vita Tour 2017 | |||

| 30 June 2017 | |||||

| 15 July 2017 | U2 | Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds | The Joshua Tree Tour 2017 | 117,924 | The performance of "The Little Things That Give You Away" was recorded for the group's live album Live Songs of iNNOCENCE + eXPERIENCE. |

| 16 July 2017 | |||||

| 11 June 2018 | Vasco Rossi | VascoNonStop Live 2018 | |||

| 12 June 2018 | |||||

| 16 June 2018 | Fabrizio Moro | Parole, rumori e anni Tour | |||

| 23 June 2018 | Cesare Cremonini | Stadi 2018 | |||

| 26 June 2018 | Pearl Jam | Pearl Jam 2018 Tour | 50,000 | ||

| 30 June 2018 | Negramaro | ||||

| 8 July 2018 | Beyoncé and Jay-Z | On the Run II Tour | 40,440 | ||

| 16 June 2019 | Ed Sheeran | James Bay, Zara Larsson | ÷ Tour | 58,959 | |

| 29 June 2019 | Laura Pausini and Biagio Antonacci | Laura Biagio Stadi Tour | |||

| 4 July 2019 | Ultimo | ||||

| 12 July 2019 | Ligabue | Start Tour 2019 | |||

| 20 July 2019 | Muse | Mini Mansions, Nic Cester | Simulation Theory World Tour | 50,385 | |

| 15 June 2022 | Cesare Cremonini | ||||

| 18 June 2022 | Antonello Venditti and Francesco de Gregori | ||||

| 22 June 2022 | Ultimo | Marco Mengoni | |||

| 24 June 2023 | Tiziano Ferro[70] | Il mondo è nostro Tour | |||

| 25 June 2023 | |||||

| 12 July 2023 | Depeche Mode | Hælos | Memento Mori World Tour | ||

| 14 July 2023 | Ligabue | Stadi 2023 | |||

| 18 July 2023 | Muse | Royal Blood | Will of the People World Tour | ||

| 20 and 21 July 2023 | Måneskin | Loud Kids Tour | |||

| 23 July 2023 | Pinguini Tattici Nucleari | Stadi 2023 | |||

| 12 July 2024 | Coldplay | Music of the Spheres World Tour | |||

| 13 July 2024 | |||||

| 15 July 2024 | |||||

| 16 July 2024 |

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 "Decreto 3 febbraio 2004. Conferimento di beni immobili patrimoniali dello Stato, ai sensi dell'art. 8, comma 6, del decreto-legge 8 luglio 2002, n. 138, convertito in legge, con modificazioni, nella legge 8 agosto 2002, n. 178" [Decree of 3 February 2004: assignment of the estate owned by the State]. Official Gazette of the Italian Republic. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato (39). 17 February 2004. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

Ravvisata l'opportunità di individuare tra gli immobili da conferire in proprietà alla CONI Servizi S.p.A. quelli facenti parte del complesso del Foro Italico, in Roma, non aventi requisiti storico-artistici e quindi suscettibili di alienazione ai sensi del decreto del Ministro del tesoro, del bilancio e della programmazione economica […]

- 1 2 "Decreto del Presidente del consiglio dei ministri 17 giugno 2021. Modalità di attuazione del trasferimento di beni immobili destinati al Comitato olimpico nazionale italiano (CONI)" [Prime Minister's decree of 17 June 2021: implementation of the transfer of real estate assigned to the Italian National Olympic Committee]. Official Gazette of the Italian Republic. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato (214 serie generale). 7 September 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

[…] conseguentemente, ogni richiamo alla Coni Servizi S.p.a. contenuto in disposizioni normative vigenti deve intendersi riferito alla Sport e Salute S.p.a. […]

- 1 2 "Impianti di serie A – stagione 2017/2018" [Serie A venues season 2017/2018] (PDF) (in Italian). Rome: Osservatorio Nazionale sulle Manifestazioni Sportive del Ministero dell'Interno. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ↑ Gianni Puccini (17 May 1953). "In 100.000 allo Stadio Olimpico" [100,000 at the Olympic Stadium] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 4. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ↑ Marinella Venegoni (6 June 1998). "Baglioni, strada facendo c'è il record all'Olimpico" [Baglioni, along the way there's the attendance record at the Olympic Stadium]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. p. 13. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ↑ Mario Luzzatto Fegiz (21 May 2015). "Tutto Baglioni in concerto" [All Baglioni in concert]. Corriere della Sera. Milan. Archived from the original on 27 May 2023. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ↑ (Rossi & Gatti 1991, pp. 12–15)

- 1 2 3 (Rossi & Gatti 1991, pp. 44–48)

- 1 2 "Il popolo italiano esalta oggi nella Vittoria le gloriose virtù della stirpe auspicio del sicuro domani" [The Italian people today hails in the Victory the glorious virtues of the lineage as a hope for a bright tomorrow]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. 4 November 1932. p. 1. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ Diego Angeli (23 October 1932). "Dove sorge il Foro Mussolini" [Where does the Foro Mussolini stands]. La Stampa. Turin. p. 3. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Lo Stadio dei Cipressi" [The Stadium of Cypresses]. Stampa Sera (in Italian). Turin. 27 October 1932. p. 3. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (Rossi & Gatti 1991, pp. 351–53)

- 1 2 "Le nuove opere che l'O.N.B. inaugurerà al Foro Mussolini" [The new venues to be opened by ONB at the Foro Mussolini]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. 16 April 1937. p. 2. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ "La fervida attesa di Roma" [The ardent waiting of Rome]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. 3 May 1938. p. 2. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ "Il Duce assiste allo Stadio Olimpiaco al saggio conclusivo del X Campo DUX" [Duce attends the final gymnastics exercises of the X Campo DUX]. il Littoriale (in Italian). 29 August 1938. p. 1. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ "L'opera di un anno per la creazione di un nuovo ordine" [The work of a year for the establishment of a new order]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. 28 September 1941. p. 6. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ "Con cavalleresca emulazione gli Atleti Alleati hanno concluso le gare al "Foro d'Italia"" [With great chivalry the Allied forces have closed the games at the Foro d'Italia]. Corriere dello Sport. Rome. 17 July 1944. p. 1. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- 1 2 "Stadio dei Centomila costruito a rate" [Stadio dei Centomila built in small steps]. Stampa Sera (in Italian). Turin. 14 October 1949. p. 4. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ Gabriele Isman (24 August 2010). "Così le Olimpiadi hanno cambiato Roma" [Thus the Olympics transformed Rome]. la Repubblica (in Italian). Rome. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- 1 2 Bruno Roghi (24 January 1951). "Il CONI è entrato allo Stadio cappello in mano e borsa aperta" [CONI entered the stadium hat in hand with open pockets]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. p. 4. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ Arrigo Morandi (20 July 1951). "Governo, scuola, C.O.N.I e sport" [Government, school, CONI and sports] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 4. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ Arrigo Morandi (14 September 1951). "I beni ex-GIL" [The ex-GIL estate] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ Flavio Gasparini; Antonio Perria (9 February 1958). "Ipoteca di tre miliardi sugli impianti del Foro italico per finanziare la speculazione clericale ENAL-Lotto" [Three-billion mortgage over the Foro Italico complex to finance the clerical speculation Enal-Lotto] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 1. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ↑ "Commissariato per la Gioventù Italiana" (in Italian). Ministero della Cultura. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- ↑ "Tabella dei beni immobili di proprietà della Gioventù Italiana trasferiti al demanio ai sensi dell'articolo 2" [List of the estate owned by the Gioventù Italiana transferred to the State according to the Article 2]. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana (in Italian). Rome: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato. 117 (13): 373. 16 January 1976. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 (1960 Olympics).

- ↑ Gianni Puccini (17 May 1953). "In 100.000 allo Stadio Olimpico" [100,000 at the Olympic Stadium] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 4. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ Giuseppe Signori (18 May 1953). "Ungheria – Italia 3-0" [Hungary 3:0 Italy] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 3. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ Attilio Camoriano (18 May 1953). "Minardi vince la Napoli-Roma" [Minardi wins the Naples - Rome stage] (PDF). l'Unità. Rome. p. 6. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ Vittorio Finizio (25 May 1953). "Juventus – Lazio 1-0 (1-0)". Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). Rome. p. 1. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ "Roma - Spal 0-0". Corriere dello Sport (in Italian). Rome. 1 June 1953. p. 1. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ "Cronache dello sport" [Sports reports]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. 25 April 1954. p. 4. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ↑ Remo Gherardi (25 April 1954). "Ai "tricolori" di Francia la Coppa Europa di rugby" [To the Tricolours of France the rugby union European Cup] (PDF). l'Unità. Rome. p. 7. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ↑ "Deciso stamane: Olimpiadi a Roma" [Decided this morning : the Olympics to Rome]. Stampa Sera (in Italian). Turin. 16 June 1955. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ↑ Alberto Marchesi (19 October 1959). "Un derby sdrammatizzato dal tabellone luminoso" [A derby lightened up by the new scoreboard]. Corriere dello Sport. Rome. p. 2.

- ↑ "Aperti i giochi olimpici" [The Olympic Games have been opened] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. 26 August 1960. p. 1. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ "Le medaglie di ieri: sei USA e tre URSS" [Yesterday's medals : six for the USA and three for the USSR] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. 3 September 1960. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- 1 2 Remo Gherardi (6 September 1960). "Rudolph: splendido bis nei 200 m" [Rudolph wonderfully repeats herself on the 200 metres] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- 1 2 "«Mondiale» delle ragazze USA: 44"4" [World record of the USA girls: 44"4] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. 8 September 1960. p. 6. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ "In nessuno stadio del mondo si erano mai viste cose simili" [In no stadium such things were seen before] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. 7 September 1960. p. 5. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ Vittorio Pozzo (8 June 1964). "Bologna - Inter 2 a 0. I rossoblù campioni d'Italia" [Bologna v Inter 2-0: The Red and Blues are Italian champions]. Stampa Sera (in Italian). Turin. p. 7. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ Albert Barham (10 May 1968). "Mullery a challenge to Stiles". The Guardian. London. p. 23. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ Albert Barham (10 June 1968). "England were the most effective team in Rome". The Guardian. London. p. 15. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ↑ "Italy are the new champions of Europe". The Guardian. 11 June 1968. p. 15. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ "Juventus Independiente forse finale Intercoppa" [Juventus v Independiente probable Inter-Cup final]. Stampa Sera (in Italian). Turin. 26 October 1973. p. 12. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ "Juventus, sì all'Independiente" [Juventu say "yes" to Independiente]. Stampa Sera. Turin. 31 October 1973. p. 12. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ Giovanni Arpino (29 November 1973). "È già Natale per i Gauchos" [For the Gauchos is already Christmas]. La Stampa (in Italian). Turin. p. 18. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ Oreste Pivetta (7 September 1974). "Vince Mennea, festa all'Olimpico" [Mennea wins, the Olympic stadium celebrates] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 12. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ Oreste Pivetta (4 September 1974). "Borzov «brucia» Mennea e Bieler nei 100" [Borzov freezes Mennea and Bieler in the 100 metres] (PDF) (in Italian). Rome. p. 12.

- 1 2 Oreste Pivetta (9 September 1974). "10 ori alla Germania Democratica!" [10 gold medals to the DDR!] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 6. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ "I Giochi mondiali di atletica a Roma" [The athletics University Games to Rome] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. 26 February 1975. p. 10. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ "Jugoslavia: rinuncia definitiva alle Universiadi" [Yugoslavia definitely resigns the organization of the Universiads] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. 29 November 1974. p. 10. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ Remo Musumeci (20 September 1975). "Mennea sfreccia nei 100 metri" [Mennea sprints in the 100 metres] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 12. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- 1 2 Remo Musumeci. "Mennea: disinvolto bis nei 200. Fava: esaltante bis nei 5.000" [Mennea: comfortable sprint in the 200 metres. Fava: brilliant extra in the 5,000 metres] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 9. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ Remo Musumeci (19 September 1975). "A Fava i 10.000 m. Bottiglieri-record" [Fava wins the 10,000 metres. Bottiglieri marks a record] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 10. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ David Lacey (25 May 1977). "Up, up and away". The Guardian. London. p. 24.

- ↑ David Lacey (26 May 1977). "Smith goal ends an era with triumph". The Guardian. London. p. 22.

- ↑ "In Italia le finali della Coppa Europa di calcio del 1980" [To Italy the 1980 Euro final tournament] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. 14 November 1977. p. 14. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ "No breathing space for the new England manager". The Guardian. London. 14 November 1977. p. 18.

- ↑ Loris Ciullini (12 June 1980). "Menicucci è tornato all'Olimpico" [Menicucci back to the Olympic Stadium] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 19. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ Giuliano Antognoli (12 June 1980). "RFT, primo passo verso il titolo?" [FRG, first step to the title?] (PDF). l'Unità. Rome. p. 19. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ Loris Ciullini (15 June 1980). "La Cecoslovacchia punta alla «piccola» finale" [Czechoslovakia eyes the bronze final] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 15. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ↑ Giuliano Antognoli (23 June 1980). "Il Belgio non blocca la marcia della RFT" [Belgium cannot stop FRG's march] (PDF). l'Unità (in Italian). Rome. p. 9. Retrieved 17 June 2023.

- ↑ "Stadio Olimpico – nuove tecniche di safety & security". Vigili del Fuoco. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ↑ "football stadium attendance". Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ↑ "Full Time Summary – Turkey v Italy" (PDF). UEFA. 11 June 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ↑ "Full Time Summary – Italy v Switzerland" (PDF). UEFA. 16 June 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ↑ "Full Time Summary – Italy v Wales" (PDF). UEFA. 20 June 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "Full Time Summary – Ukraine v England" (PDF). UEFA. 3 July 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ↑ Meo (Caporedattore), Oriana (28 April 2023). "Tiziano Ferro: a sorpresa arriva il nuovo singolo inedito 'Destinazione Mare'". All Music Italia (in Italian). Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

Bibliography

- "The Olympic Stadium" (PDF). The XVII Olympiad Rome 1960. International Olympic Committee. I: 56–57. 1960. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- Rossi, Piero Ostilio; Gatti, Ilaria (1991) [1984]. Roma. Guida all'architettura moderna 1909-1991 (in Italian) (2 ed.). Bari-Rome: Laterza. ISBN 88-420-2509-7.

External links

- External view of the Olympic Stadium of Rome

- Rome2009.net

- Brief Guide to Olympic Stadium of Rome

- How to reach the Olympic Stadium of Rome

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Summer Olympics Main venue (Olympic Stadium) 1960 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | UEFA European Championship Final venue 1968 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | European Athletics Championships Main venue 1974 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Summer Universiade Main venue 1975 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | European Cup Final venue 1977 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | UEFA European Championship Final venue 1980 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | European Cup Final venue 1984 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | IAAF World Championships in Athletics Main venue 1987 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | FIFA World Cup Final venue 1990 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | UEFA Champions League Final venue 1996 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | UEFA Champions League Final venue 2009 |

Succeeded by |