The Soap Box Derby is a youth-oriented soap box car racing program which has been running in the United States since 1934. Proclaimed "the greatest amateur racing event in the world," the program culminates each July at the FirstEnergy All-American Soap Box Derby World Championship held at Derby Downs in Akron, Ohio, with winners from their local communities travelling from across the US, Canada, Germany and Japan to compete. 2023 marked the 85th running of the All-American since its inception in 1934 in Dayton, OH, having missed four years (1942-1945) during World War II and one (2020) during the COVID pandemic. Cars competing in the program race downhill, propelled by gravity alone.

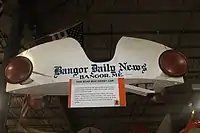

The Soap Box Derby expanded quickly across the US from the very beginning, bolstered largely by a generous financial campaign by its national sponsor, Chevrolet Motor Company. At the same time there was enthusiastic support from coast to coast of numerous local newspapers that published aggressively during the summer months when races were held, with stories boasting of their own community races and of their Champion travelling to Akron with dreams of capturing a National title and hometown glory. In 1936 the All-American had its own purpose-built track constructed at what is now Derby Downs, with some communities across America following suit with tracks of their own.

Its greatest years occurred during the Fifties and Sixties when viewer turnout at the All-American reached 100,000 spectators, and racer participation was at an all-time high. From the very beginning, technical and car-design innovation happened rapidly, so Derby officials drafted ways of governing the sport so that it did not become too hazardous as speed records were being challenged. At Derby Downs the track length was shortened twice to slow the cars down.

The seventies brought significant changes, beginning with the introduction of girls to the sport in 1971. The following year Chevrolet dropped its sponsorship, sending Derby Downs into a tailspin that threatened its very future. Racer enrollment plummeted the following year. In 1973 a scandal hit Derby Downs with the discovery that their World Champion had cheated, and was thus disqualified, further exacerbating an uncertain future. In 1975 Karren Stead won the World Championship, the first of many girls that would go on to claim the title. Finally there was Derby's decision to divide the competition with the introduction of the Junior Division kit cars in 1976.

As fiscal challenges continued, the Derby instituted new guidelines by redrafting the Official race divisions into three: Stock, Super Stock and Masters. With it came the availability of the prefabricated fiber glass kit racers which kids could now purchase, this to appeal to a new generation of racers uncomfortable with constructing their own cars from scratch, as well as to help Derby effectively meet its financial obligations. Leading into the 21st Century it has continued to expand with the inclusion of the Rally Program racers at the All-American in 1993, the creation of the Ultimate Speed Challenge in 2004 and the Legacy Division in 2019.

Introduction

The Soap Box Derby, promoted as "the greatest amateur racing event in the world,"[1] is a largely volunteer-driven,[2] family-oriented sporting activity for youth conducted across the US and around the world. Local or regional races are held yearly, with winners from each sent to compete at the All-American Soap Box Derby World Championship, officially the FirstEnergy All-American Soap Box Derby World Championship,[3] which occurs every July at Derby Downs in Akron, OH. Oversight is by the All-American Soap Box Derby organization, or AASBD, run by a paid administrative staff[2][4][5] headquartered at Derby Downs.

The name Soap Box Derby[lower-alpha 1] is a registered trademark,[1] and used to identify the sport overall, with those actively involved referring to it simply as "Derby." The official name FirstEnergy All-American Soap Box Derby is used solely to identify the annual World Championship race itself, and referred to similarly as "the All-American."[6][7]

Eligibility to race in the Soap Box Derby is open to anyone aged 7 through 20, with participants divided by age into three Divisions, with a specific car design assigned for each: Stock, the entry level Division for ages 7–13, Super Stock, for mid-level kids ages 9–18, and Masters, the senior level for ages 10–20 and a design where the occupant rides in the fully reclined position. Cars come un-assembled in kits purchased from the AASBD, the only visibly common component of all three designs being the Official wheels sets which are available for purchase as well.[8]

While working with a mentor is permitted, kids are expected to assemble the cars themselves in order to develop the skills necessary for the car to pass inspection before they are qualified to race.

Beginnings

Kids playing on home-made scooters and go karts in the 1930s was not an unfamiliar sight in the streets of America, and racing in organized events was an inevitable outcome of it. As early as 1904 Germany conducted its first soapbox race for kids, and in 1914 there was the Junior Vanderbilt Cup in Venice, CA that held a kids race as well.[lower-alpha 2]

The Soap Box Derby story began on June 10, 1933[10] when six boys were racing homemade push carts in Dayton, OH, among them William Condit whose father suggested they have a race and that he would contact the local newspaper to have them cover it. The other participants were Dean Gattwood, Tracey Geiger, Jr., Robert Gravett, James P. Hobstetter and William Pickrel, Jr.. Of the six, Condit won that race, with Gravett taking second.[11]

Myron Scott, a 25-year-old photojournalist for the Dayton Daily News looking for ideas for its Sunday Picture Page, was one of two photographers that got the call,[10][13] and accepting the assignment ventured out to investigate. Seeing the appeal of a kids story like this he asked the boys to return in two weeks with more of their friends so he could host a race of his own. When they did nineteen showed up, bringing with them racers made of packing crates and soap boxes, sheets of tin and whatever else they could find. The race was held on Big Hill Road in Oakwood,[14] a south-side neighborhood of Dayton, with a crowd of onlookers coming to watch. Seizing on a publicity opportunity, Scott decided to plan an even bigger city-wide event with the support of his employer, the Dayton Daily News, which recognized the hope-inspiring and goodwill nature of the story—especially during the Depression. It posted advertisements of it almost daily to stir interest, and included an application which stipulated "for anything on four wheels that will coast"[10][15] for the kids to fill out. A date was set for August 19, 1933 to host a parade,[14] the race to occur a day after, and the location chosen as Burkhardt Hill, a straight, westbound slope on Burdhardt Ave[lower-alpha 4] east of Downtown Dayton.

On the appointed weekend a turnout of 460 kids along with 40,000 onlookers[14] caught everyone by surprise, and Scott knew he was onto something big. From the original 460 cars, 362 were deemed safe enough to participate,[16] including Robert Gravett, the only boy from the original Oakwood six that made an appearance.[10] At day's end sixteen year old Randy Custer (pictured), who also hailed from Oakwood, took the championship in his "slashing yellow comet"[15] on three wheels, with eleven year old Alice Johnson—who shocked many when they saw she was a girl after removing her helmet—taking runner-up.[17][2]

Scott immediately set about making the race an All-American event the following year, and sought a national sponsor, selling the idea successfully[18] to the Chevrolet Motor Company to co-sponsor with the Dayton Daily News. He was also able to induce many newspapers from coast to coast to sponsor local races on the merits that the story would increase circulation. From the photographs taken at the very first race of the six boys, he selected runner-up Robert Gravett's entry as the archetypal soap box car, and designed it into the national logo along with the now official name, Soap Box Derby, which became a registered trademark.[19]

First All-American

The very first All-American Soap Box Derby race was held on August 19, 1934 at the same location as the Dayton city-wide race in 1933, on a track that measured out at 1,980 feet. Watched by a crowd estimated at 45,000,[20] boys from 34 cities competed in the all day affair, with Robert Turner of Muncie, Indiana, piloting a car riding on bare metal wheels with no bearings, becoming the first All-American Champion. Charles Baer of Akron won the All-Ohio Championship, and in a separate race category called Blue Flame for boys aged 16 to 18, Eugene Franke of Dayton, piloting a scaled-down version of a professional motorized racer, took the crown.[20]

In 1935 Akron civic leaders convinced program organizers to move the event to Akron, OH due to its central location and hilly terrain. A long, eastbound grade on Tallmadge Ave. located at the east end of the city,[lower-alpha 5] and the site of 1934 Akron local race, was used for this year's national event, and a date was set for August 11, 1935. Scott decided to discontinue the Blue Flame race category as turnout last year was low. Fifty-two champs from across the nation made the trip to Akron, greeted by a throng of 50,000 on race day, with Maurice Bale of Anderson, IN in a sleek, metal-clad racer taking the top prize. One mishap was an accident that captured the public's interest, even boosting the event's profile worldwide, when a car piloted by Oklahoma City's Paul Brown went off the track and struck NBC's Graham McNamee and Tom Manning while they were broadcasting, an incident that continued being described live on the air as it happened.[21]

Marketing the Derby

The Soap Box Derby swept across America quickly during the Depression with dreams of winning the All-American becoming quite popular with boys. Within a year of its inauguration tens of thousands of them were constructing racers.[22][23] The added inducement of winning a college scholarship was also a chance at a more promising future,[24] particularly when life was a challenge for many.[25] Print media made celebrities of Derby champs, their faces appearing on the front page of every newspaper that covered an event.[26]

Chevrolet's campaign in promoting the Derby promulgated these ideas. However Chevrolet's sponsoring of the Derby was ostensibly a money-making enterprise,[23] and with the Depression well underway by 1934 and programs like the WPA being implemented to bolster the economy,[27] the idea of a kids' recreational program like the Derby—boys in cars—seemed an excellent marketing opportunity to sell its main product—cars—to their parents. During the Depression kids had little access to organized activities like team sports or television,[28] so getting them get behind a singular national event like Derby was an easy sell with an undeniable appeal. Chevrolet dealerships acted as agents for the Derby, where kids would go to sign up and purchase wheels and axles to get started on their cars, and since a child was usually accompanied by a parent, what better way to get mom or dad—who waited patiently while their child filled out an application—to check out the latest models in the showroom.[29]

Awards

Awards at the All-American started with the first-place silver trophy and a four-year college or university scholarship of their choice. Second and third place were awarded a brand new Chevrolet[2] and a smaller silver trophy similar in design to the first place award. Technical awards went to the best constructed (C.F. Kettering Trophy)[30] and best upholstered entries, as well as the car with the best brake. At the local level, boys that won and qualified to attend the All-American were awarded the M. E. Coyle (silver) Trophy, named after Chevrolet General Manager (1933-1946) M. E. Coyle (1888-1961),[31] and a cash prize. Beginning in 1950, they received the T. H. Keating Award plaque, named after Chevrolet Sales Manager T. H. Keating.[32] Technical honors for cars with best construction, best upholstery and best brake were awarded as well.

Derby Downs

Because of the growing popularity of the event, a larger and more permanent home was needed, and a dedicated track was constructed in 1936.[2] Chief among those that spearheaded the project were Bain “Shorty” Fulton, manager of Akron's Fulton Airport, and Jim Schlemmer, sports editor of the Akron Beacon Journal. A site[lower-alpha 6] was chosen by the airport, a tract of land occupied at the time by a ski slope, which the City of Akron agreed to lease to the Soap Box Derby organization for $1 per year. Following its announcement on July 29, 1936, construction began on a 1,600 feet (490 metres) paved track with landscaping, installation of the rented grandstands and bleachers, and the erection of a wooden, two-deck bridge over the finish line, all by WPA workers. Of the 1,600 feet, 1,175 feet (358 metres) of it was the race course, with the top staging area and bottom run-out comprising the remainder. Extensive infrastructural provisions were made for the expected media as well.[21]

Exactly three weeks later, on August 16, 1936, the first All-American at Derby Downs (officially the 3rd All-American) was run. A pre-race parade with 11 bands entertained a throng of nearly 100,000 who were welcomed officially by Governor Martin L. Davey and Mayor Lee D. Schroy. Competing in the race were 116 boys from across America and one from South Africa, making this the first World Championship. Witnessed by a cadre of 500 media personal from around the globe was 3rd All-American Champion Herbert Muench, Jr. 14, of St. Louis, MO taking home the top prize of a $2,000 four-year college scholarship.

Now that Derby had a home it was able to cater to the increasing participation of still more communities organizing additional local races and sending champs of their own. At the Inaugural All-American the number of boys that entered was 34, but by 1936 that number had exploded to 116. In 1939 there were 176 cities that wanted to participate, but due to Derby Downs' limit to just 120 cars at the time, some communities had to double up or hold regional races in order to send just one boy representing multiple communities instead of two or more. Even by 1935 there were an estimated 50,000 boys across America that were already building cars in order to participate.[33][34]

In 1940 the popularity of the sport meant that the All-American would accommodate 130 cars from around the world, increasing to 148 by the end of the decade. In 1959 that number was raised to 170, and by 1969 a total of 257 cars came to Akron. Today the All-American comprises three Official Divisions across multiple categories, and in 2023 reached 320 participants.[35]

Classic Derby - The Golden Years

Following WWII and a return home of its service personnel, America embraced a new optimism and chance for greater prosperity, thanks partly to the G.I. Bill introduced in 1944.[36] In 1946 the Soap Box Derby returned as well, and Chevrolet wasted no time in marketing the Derby with the same amount of pomp and pageantry[37] it lavished upon the boys half a decade earlier.[38] By now the Derby was a national obsession for many boys who thought of nothing better than to construct their cars in the hopes of making it to Akron. Considered to be Soap Box Derby's heyday or "golden age," attendance at the All-American reached its peak at 100,000 each year.

Parade of celebrities

Part of the attraction of the All-American was the parade of Hollywood and well-known celebrities that made appearances annually.[39] Names like Abbot and Costello, the cast from TV's Bewitched, Lorne Greene and the cast from Bonanza, Rock Hudson, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Roy Rogers, Dinah Shore, Jimmy Stewart, and Adam West[40] were promoted by Chevrolet leading up to the race.[39] Jimmy Stewart made the most appearances in Akron, six in all—1947-1950, 1952 and 1957. Into the 1970s, other celebrities included Peter Fonda, George Takei[41] and Tom Hanks.[42]

Oil Can Trophy Race

Part of the pre-race pageantry was the Oil Can Trophy Race, introduced in 1950[43] as an exhibition event that pitted three of the guest celebrities against one another, each piloting a unique and often outlandishly-designed racer, in a downhill heat for a novelty prize, the Oil Can Trophy. Jack Dempsey, Wilbur Shaw and Jimmy Stewart were contestants in the inaugural race, with Dempsey taking the prize.[44] When Stawart returned in 1957 for what would be his final All-American appearance, he raced once more, this time against George Montgomery and Roy Rogers, with Montgomery taking the prize.[45] In 1962 it was Lorne Greene that beat fellow cast mates Michael Landon and Dan Blocker in a Bonanza-themed showdown,[46] and in 1980 Christopher George won out over wife Linda Day George and actor Bill Daily.[47] Ostensibly lighthearted in tone, the celebs usually played to the crowd for laughs.[48][49] The spectacle continued into the 2000s.

Fame through adversity

Paraded alongside Hollywood stars were Derby Downs' own champions, stories of a boy's climb from relative obscurity to national fame after achieving victory in Akron. These the media promoted eagerly as front-page heroes on a national scale,[50] some reaching legendary status depending on just how interesting or adverse the climb was.

The Graphite Kid

One such boy is Gilbert Klecan, age 14, the first World Champion following the Second World War, racing a laminate-constructed racer fitted with a streamlined windscreen and equipped with vertical steering of a unique design. A family friend named Chuck Boswell, an aerospace engineer at Convair, told Gil about the San Diego Derby and suggested he build a car that he offered to design. Accepting his offer, Gil entered the 1946 race but in an unpainted car, having just completed it the night before. Winning in San Diego, Gil became eligible to race in Akron, where his car was quickly sent while still being unpainted. When he arrived he hastily painted it before it was lettered, but felt it did little to make it smoother, so Boswell handed him a can of graphite powder, a dry lubricant, to rub all over it in the hopes that it would make the car slicker. While doing so he managed to get some on his clothes and face, giving him the look of a chimney sweep. When Gil emerged the winner at the All-American, the press eagerly snapped photos of the cheerful champ with the blackened face,[lower-alpha 7] dubbing him the "Graphite Kid."[51] His photo appeared in Life Magazine.[52]

The next day a film crew wanted to capture Gil racing down the hill, having him trail behind a pickup truck where the camera was mounted. When the director yelled "stop!," meaning "cut!," the driver of the truck heeded, while Gil, unaware, continued headlong into rear bumper, injuring his back and landing him in the hospital for a week. Gil eventually recovered.[52][53]

Graphite use continued the following year with boys like class B entrant John Englert of Iowa City, IA, even dusting his car with talcum powder over the graphite, and fellow racer Craig Penney who followed Gil's example by blackening his face.[54] New regulations in 1948 banned its use anywhere on the car or driver. Even having graphite on one's person was grounds for disqualification.[55] Gil wrote an article that appeared in Mechanix Illustrated in May, 1947 which featured construction blueprints of his racer, with details of his steering and suspension designs.[56] His car was exhibited in 2017 at the San Diego Automotive Museum in Balboa Park.[52]

Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia

A heartwarming story is Joe Lunn, who took the World Championship in 1952. Joe was a small and shy farm boy from a poor family that hailed from Thomasville, GA.[57] Visiting uncles from Columbus, GA, located 150 miles NW of Thomasville, suggested that he enter a goat cart he had built at their local Soap Box Derby race, something Joe knew nothing about.[58] With their help Joe acquired the needed wheels and axles, making changes to the cart in order to qualify, and signed up as a class B entry at the age of eleven. Arriving on race day, Joe's black racer had no sponsor and certainly looked no match against the more experienced racers that did. It was a surprise to many therefore when he took the championship. A month later he was going to Akron. To accompany him his mother Jewell borrowed the $33.87 from her brothers, Joe's uncles, for a round-trip bus ticket to Akron, having never been north of Columbus before that time.[59]

When Joe arrived in Akron he admitted that he was most impressed by how big the track at Derby Downs was, being 200 feet longer than Columbus', but reasoned that other boys probably felt as scared as he, so he pressed on. In his first heat, his steering cable snapped and he lost control of his car beyond the finish line, striking a guard rail and severely damaging its front end. Joe received a cut across the chest that left a scar and a bump to the head. At this point he was certain that he was out of the race.[60] While being patched up at the first aid station[61] he learned however that he had won, and that his car was being repaired so he could go again, something he was not happy about repeating.[58]

With race volunteers cobbling together whatever they could find—bailing wire, duct tape, even sheet metal from a flattened lunch box—Joe's car was hastily made race-worthy again. Three of the damaged wheels had to be swapped with replacements from an older set from 1947, considered by Derby fans to be some of the fastest wheels ever used on a Derby car.[62] In the four heats that followed Joe would came out on top,[63] each time winning by a larger margin. He remembers seeing pieces of his car fall off as he raced down the track each time, quickly becoming the crowd favorite as they cheered on what was affectionately dubbed "The Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech."[60] In his final heat he set the track record that day, taking the Derby crown, and becoming the first Southerner to do so.[63][58]

Joe never did go to Georgia Tech, joining the US Navy instead and staying on until 1979. His patched-together car,[lower-alpha 8] considered the worst-looking winner at the All-American, is on exhibit at the AASBD Hall of Fame Museum in Akron.[62]

Doug Hoback

A story of courage that made international news was of a boy determined to win one more Soap Box Derby race while battling terminal cancer. Doug Hoback hailed from Valparaiso, IN, entering his car as a class B contestant in both the Valparaiso and Gary, IN local races in 1955, winning in Valparaiso and being awarded a brand new bike.[64] In December doctors discovered that Doug had a terminal malignancy, a cancer called lymphosarcoma. His physician, Dr. Leonard Green, stated that all he could do medically was postpone death. Undaunted, Doug expressed his wish that he win next year's Soap Box Derby and earn a trip to Akron. "He never gave up," Green said. On July 4, Doug, now age 13, repeated his win in Valparaiso, this time as a class A entry,[65] and then headed to Gary to compete for the regional title and a chance at Akron. On the day of that race Doug was down 40 pounds from his usual 110 pound weight, and at the time trial run he had to be helped in and out of car due to his weakened condition. When an axle broke halfway down the track, his car veered into the guard rail, ending his chance to compete. Uninjured, he continued to watch the race from the sidelines, seated in his wheelchair.[66] The following day his parents returned from church to find their son's condition had worsened. After being rushed to the hospital in Valparaiso he passed away two hours later.[67] "He just gave up," said his father, once he lost his shot at Akron.[68]

Doug's story appeared in newspapers across the US and in Canada[lower-alpha 9] telling of his courageous battle. Tom Brown, 13, who raced in Valparaiso the year prior, winning the class A title, and was a pallbearer at Doug's funeral, spoke well of his best friend. When Doug was awarded another bike in this year's race he gave it to Tom, who had his stolen the week prior.[66] To honor Hoback the Gary Soap Box Derby created the Doug Hoback Memorial Award, inaugurated in 1957 with recipient Tommy Osburn[69] and continuing into the Seventies, awarded to competitors demonstrating courage and outstanding sportsmanship.[70] His extant brown racer is currently located in Akron, OH, owned by a private collector.

Stephen Damon

Derby was an attractive activity for all kinds of kids, including Stephen Damon of Norfolk, VA, who raced in the Tidewater, VA Soap Box Derby local race in 1964 and 1965. His brother Wally, 14, raced also. Unlike most that participated, Stephen was almost completely blind, with 2 percent vision in one eye. Yet as expected with all participants he had to construct his own racer, understandably with the help of his father, Wallis Damon Sr., who would show him where to drill or cut. According to Derby rules he was also expected to drive his own car, and entering his first year he worked out a modern solution by following instructions sent by radio to a receiver in his helmet. The words "radio dispatched" were painted on his class B racer. He was sponsored by the Naval Aviation Safety Center, who loaned the radio equipment. Not quite getting the hang of its use he crashed into a fence at the bottom during his first try. The following year when Stephen was 13-years-old, Navy Commander Richard E. McMahon (1924-2013),[71] an administrator at the Norfolk Naval Air Station, stood watch as Stephen's eyes, talking him calmly down the hill, with Stephen successfully winning his first heat. He was bested in the next heat by Gary Osman, who became overall champ that day.[72] Stephen was enrolled at the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind.[73]

The Derby family

This period witnessed the growth of the Derby family[74] (pictured), with fathers who were once racers themselves now putting their own sons into cars to compete. Often with mom's help or support, even sister, an uncle or cousin throwing in, Derby became a family enterprise where two or more brothers would possibly compete against one another in their local race, or a boy would build a car for each year he competed,[lower-alpha 10] passing it down to a younger sibling as he outgrew it. Soap Box Derby's "boy built" rule was understood—albeit frivolously—to mean that dad could help to some degree with his son's construction of the car, which was most often the case,[77] but the outcome meant that father and son worked together, forging a healthy and long lasting relationship that became the backbone of the Soap Box Derby.[78] As with any sport involving family participation, there were parents wanting nothing more than to win at all cost, particularly since the stakes were so high, with a kid acting simply as jockey, piloting a car that was built by an adult or hired professional.[77][79] This became a growing concern and constant complaint heard around various races,[lower-alpha 11] with officials eventually taking measures to guard against such occurrences.[79]

With each year, Derby regulations were amended and standardized to ensure the safety of drivers.[55] After the war the use of windscreens on cars were still allowed, but by 1948 they were banned outright. Wheels were also standardized with the introduction of the Official Soap Box Derby Tire and axle set that a boy could purchase at his neighborhood Chevy dealership. Weight and dimension restrictions of the car remained generally the same during this time, but as more subtle rules changes were being introduced by the late Sixties, car designs became more creative[80] and even outlandish in response.[81]

Ken Cline

A Derby family success story is that of Ken Cline, 1967 World Champion and AASBD Hall of Fame inductee in 2017.[82] Ken came from a large family of nine kids, each having raced in the Soap Box Derby. Their father was regional manager for Northern Natural Gas and relocated often. While the family was living in Midland, TX, brothers Richard and Michael won that local's races in 1964 and 1965, respectively, with both going to Akron. Ken raced in Midland in 1966 and was favored to win, but a rain-soaked track hampered his car. The following year he won in Lincoln, NE when they lived there[83] and went on the take the All-American crown a month later. Sister Rita went to Akron in 1972 having won in Amarillo, TX.

Ken's win in Akron happened during Derby's peak, in a car of unprecedented design. Called 'the Grasshopper," a name he disliked at first since his name for it was "Experimental III," it was a low profile, needle-nosed racer with a short wheelbase, the minimum allowed. It was also the first World Championship car having the front axle placed rearward,[83] a trend that continued well into the Seventies. From among the numerous awards in the technical achievement categories he received the Best Designed trophy at the All-American on top of his competitive win.

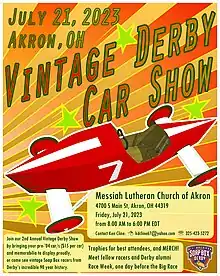

Continuing the family tradition, Ken's daughter Alethia won the local championship as a Senior Division entry in Chicago, IL in 1987, becoming the first child of a World Champion to race in Akron and advancing to the second round after beating the Akron Champ in the first.[84] His son Houston raced also in the Junior Division.[85] Cline became director of the Lincoln, NE local race, and helped organize the Greater Chicago Soap Box Derby when he moved there in 1986. After becoming its director he served as regional director for Midwest states in 1990. Cline was part of the team that developed and designed the pre-fabricated, fiber glass shell Stock Car introduced in 1992. It is still being used today.[86] He is founder and director of the Annual Vintage Derby Car Show taking place each July in Akron, OH during Race Week.[87] His extant car is on exhibit at the AASBD Hall of Fame Museum at Derby Downs.

The Seventies

In the late Sixties enrollment at the Soap Box Derby was at an all-time-high, with craftsmanship and car design exploring innovative new concepts that favored drivers in a full lay-down position instead of the standard sit-up configuration. At the onset of the 1970s Derby Downs was confronted with social pressure brought on by the Women's Liberation Movement demanding that institutions like the Soap Box Derby embrace more modern trends. In 1971 it was announced therefore that girls would be allowed to race for the first time.

Girls join Derby

In 1933 Alice Johnson (1921-1985) was one of two girls[2] to race at the very first city-wide soap box race in Dayton, having constructed her car with the help of her father, Dayton aviator Edward "Al" Johnson. Taking second, she was awarded a bouquet of flowers from winner Randall Custer, and a boy's bike. The following year she raced again in the Dayton local race, taking third.[40]

No Derby Rule Book ever stated that girls were unable to compete officially, but it was suggested in the language of promotional material and newspaper advertisements, with Chevrolet dealerships even refusing to accept girl applicants or sell them wheels and axles.[88] There was also resistance from many, including its founder Myron Scott, who stated that he devised the sport to be exclusively 'boys only' from the start.[12] Counter to this, popular opinion was positing a more liberal stance, with Chevrolet receiving legal pressure from local Derby organizations wishing to enter girls. This coupled with that fact that former racers that were now dads wanted to participate in Derby once more by putting their child into a car, but only had daughters. Mason Bell, general manager of the Soap Box Derby from 1964 to 1972, knew that it was only a matter of time before girls be let in.[89]

Unlike most organized sports, the Soap Box Derby chose not to split competition along gender lines by creating a separate category for each, meaning that girls would go up against boys on an equal footing. At the 34th All-American, Rebecca Carol Phillips was the very first girl to take a run down the track at Derby Downs, racing the first heat in lane 1, and winning it.[90] The following year two girls cracked the top ten in a field of 236 entries: Priscilla Freeman of Chapel Hill, NC, who took 5th, and Karen Johnson of Suburban Detroit, MI, who came 7th.[91] In no time the girls equaled the boys,[92] and in 1975 the first female World Champion honor fell to Karren Stead, 11, (her car pictured) of Lower Bucks County, PA., who not only won but did so in an arm cast[lower-alpha 12] she acquired a few days earlier after an injury at Derby Camp.[93]

Chevrolet bows out

By the Sixties there were concerns among Derby officials about Chevrolet's continued sponsorship of the Soap Box Derby, filling Derby Downs with a sense of uncertainty leading up to the Seventies. Till now Chevrolet was the Derby's sole national sponsor, but questions within the General Motors management was whether it was still benefiting from its investment. Derby general manager Mason Bell was aware of these concerns and worked tirelessly to keep Chevrolet on board as long as possible. GM general manager John DeLorean stated on record that he felt the Derby was outdated and too expensive to hold,[94] so the hard decision fell to him, and on September 28, 1972 it was announced that Chevrolet would end its sponsorship.[95] The Akron Chamber of Commerce stepped up to ensure that the World Championship race the following year would take place,[96] but the budget could not come close to match Chevrolet's nearly $1 million[2] annual budget, though Chevrolet did pledge a final $30,000 for the 1973 race. They also transferred all rights and chattels over to the new sponsor for a single settlement of $1, including the Soap Box Derby name and logo, and capital used in staging the All-American like structures, finish-line bridge, bleachers and equipment.[97] The All-American was held successfully in 1973, but enrollment had dropped by almost half.[12]

The cheating scandal

Following Chevrolet's stepping down as national sponsor, Derby Downs was beset by a cheating scandal that threatened to damage its credibility as a trusted American institution. In 1973, World Champion Jimmy Gronen, 14, of Boulder, Colorado was stripped of his title just two days after being crowned the winner after he was caught cheating.[2] Unusual discrepancies surrounding Gronen's margins of victory and heat times tipped off Derby officials, and an investigation of his car (pictured left) was conducted using X-ray examination, which revealed an electromagnet in the nose of the car, along with electrical wires connected it to a battery. By Gronen leaning his helmet against a switch hidden in the helmet fairing (pictured right) of the car's body, the electromagnet became charged, effectively making the nose of the car grab the steel plate of the starting gate. When the gate swung forward, freeing the cars so they could start their run, Gronen's car was pulled forward as well, giving it a boost. Videotape of the race showed a suspiciously sudden lead for Gronen just a few feet after each heat began. Other suspicions were Gronen's heat times progressively slowing down as the race wore on—heat times usually get faster each time a racer completes a heat—as the battery drained power each time the circuit was closed, reducing the effectiveness of the magnet. The margin of victory for a race heat is normally no more than 1 to 3 feet (0.30 to 0.91 m). Gronen's early heat victories were in the 20 to 30 feet (6.1 to 9.1 m) range.[98]

Midway through the race, Derby officials also replaced Gronen's wheels after chemicals were found to be applied to the wheels' rubber. The chemicals caused the tire rubber to swell, which reduced the rolling resistance of the tire. In the final heat, Gronen finished narrowly ahead of Brent Yarborough, who was declared the 1973 champion two days later.

Gronen's uncle and legal guardian at the time, wealthy engineer Robert Lange, was indicted for contributing to the delinquency of a minor and paid a $2,000 settlement.[99]

Derby rebuilds

By the end of the year the Akron Chamber of Commerce severed ties with the Derby Downs, which now needed a new sponsor. The next month the Akron Jaycees Junior Chamber of Commerce instituted the "Save the All-American Committee", which became the All-American Soap Box Derby, Inc. led by Ron D. Baker, general manager at Derby Downs from 1974 till 1977.[100] In preparation for the 1974 season, new rules were instituted to govern against the possibility of a repeat of previous year's cheating scandal. The gates at the starting line were rendered magnet-proof, and pre-race inspections now involved questioning the boys to verify whether they did in fact construct their racers. The cars themselves had to be constructed in a way that judges could now inspect their interiors from front to back to uncover anything suspect, meaning access doors had to be designed into the car bodies, usually over the front and rear axles. Local sponsors sending a champion to the Akron had to sign an affidavit attesting to the legal compliance of the car being shipped.[101]

The 1974 All-American race was a success, though again the attendance had dropped, and three cars were disqualified, receiving protests from parents, yet praise from others wanting to protect the integrity of the Derby.[102] Curt Yarborough,[lower-alpha 13] 11, of Elk Grove, CA was crowned World Champion[103] in a field of 99 entries, and claiming the first back-to-back win of siblings at the All-American, following his younger brother Brent Yarborough,[lower-alpha 14] who won the year prior. [104]

New sponsor

As the 1975 season was winding down, the Soap Box Derby still had no sponsor. In late November Barberton, OH firm Novar Electronics pledged $165,000 for the All-American the following year, almost double what was spent on the previous two years combined. Novar president James H. Ott felt that loosing a popular institution like the Soap Box the Derby in Akron would be a tragedy, especially during America's bi-centennial,[105] admitting that most of the management personal, including himself, were born in Akron. The agreement with Derby Downs was to continue with the annual contribution, stipulating that it would give a three-year lead time if Novar intended to end its sponsorship, avoiding the shock of Chevrolet's stepping down a few years prior.[106] Novar's annual contributions continued until 1988[2] when a fiscal downturn forced them to withdraw.

Junior Division

Following the girl's entry into the sport that culminated in Karren Stead's World Championship win in 1975, Derby Downs implemented another big change to the All-American with the introduction in 1976 of a new race category, the Junior Division.[107] Open to kids ages ten through twelve, it became an entry-level tier with an entirely new, "patterned"[108] car design sold as a kit, with easy-to-follow instructions, and included everything except the wood and tools to build a complete racer. Kids ages twelve[lower-alpha 15] through fifteen, now identified as the Senior Division, would continue to construct cars from scratch. This now meant that the All-American would crown two champions, a Junior and Senior, making Karren Stead the last sole Champion at the All-American. Champions for 1976 were Joan Ferdinand[lower-alpha 16] of Canton, OH in the Senior Division and Phil Raber[lower-alpha 17] of New Philadelphia, OH in the Junior. 1976 also had the distinction of allowing the return of windscreens, permitted on Junior cars only—Raber's champ car had one—but this was discontinued the following year and has remained so ever since.

Expansion

The years leading into the 21st Century were occupied by administrative efforts of the Soap Box Derby to maintain fiscal solvency, with Derby Downs continuing to secure a national sponsor. In 1988 Novar's twelve-year financial campaign supporting the Derby ended, but First National Bank of Ohio[110] quickly stepped up with support of $175,000 per year for two years, plus $25,000 for promotions.[111] This was followed by candy maker Leaf, Inc. from 1993 to 1994.[112] In 1998 Goodyear made contributions as a national sponsor,[112] with NASCAR partnering with Home Depot and Levi Strauss Signature from 2002 to 2007 in support of the Derby. In 2012 FirstEnergy joined the effort with continued support through 2023.[2]

Following the creation of the second Junior Division in 1976, the names of the divisions were changed, with Senior becoming the Masters Division, and Junior becoming the Kit Car Division. Pursuant to that the first fully pre-fabricated kit racer, which meant that kid no longer had to build a car from scratch, was introduced. Designed by 1967 World Champion Ken Cline, it comprised a fiberglass body shell, floorboard, axles and hardware that a child could assemble in four hours.[2]

A third division

To expand enrollment further, Derby introduced a third category in 1992, called the Stock Division,[12] which now became the entry-level tier for drivers, with the Kit Car Division elevated to a new middle-category. This meant that there would be three champions at the All-American instead of two, each representing their division.[113] The Masters racer remained the only non-kit car that racers had to fabricate from scratch until 1999, when a prefabricated Masters kit, called the "Scottie" was made available for sale.

Since 1976, the top-tier Senior/Master Division cars were fully-reclined lay-down designs, while the Junior and Kit Car Division entries remained sit-ups. From 1992 to 1998 many Masters cars returned to the sit-up configuration, with James Marsh winning the 1998 Masters Division World Championship in a sit-up design. In 1999 a fully pre-fabricated kit for the Masters Division, dubbed the "Scottie" after Derby creator Myron Scott,[114] debuted, ending the sit-up era for top-tier racers. Today the three Official Divisions of the Soap Box Derby are Stock (formerly Junior), Super Stock, (formerly Kit Car) and Masters.

Rally Division

In 1986 the Rally Division was introduced,[107] created as a "grand-prix style" race to give competitors greater experience and the ability to race in more competitions outside their own local community. Racers would compete in a district, of which there were ten in all, amassing points while competing at several races in that district. The highest-scoring car from each district would compete at the Rally World Championship, inaugurated in 1993.[2]

International Derby

In 1936 the Soap Box Derby became an international affair when cars from outside the US participated at the All-American National race in Akron, with a competitor from South Africa in 1936[2][113] and another from Canada in 1937. Three cars from abroad entered in 1938: Canada, Hawaii (not yet a US State) and Panama, although Hawaii was permitted to participate as an American entry. Other participants since then have included Germany, Guam, Ireland,[115] Japan, New Zealand, the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Venezuela.

Canada

Canada was one of the earliest entries into organizing its own local races outside the US, chief among them the Kinsmen Coaster Classic, which debuted in Montreal in 1938.[116] Two of Canada's most prominent entries were Mission City (now Mission, BC), and St. Catharines, ON, both of whom were affiliated with the Soap Box Derby as official franchises and were qualified to sent champs to the All-American in Akron. Mission acquired the rights to the Western Canada Soapbox Derby Championships in 1946 and the Mission Regional Chamber of Commerce, previously named the Mission City & District Board of Trade, organized the event annually until 1973.[117] It resumed again in 1999.[118] St. Catharines ran races from 1947[119] till 1972. From among Canada's many attempts at capturing a World Championship, St. Catharines fared the best at Derby Downs, with Andy Vasko taking third place at the 20th All-American in 1957 against 158 other competitors.[120] In the non-competitive category honoring technical achievements, St. Catharines' Ken Thomas took home the Best Construction Award at the 30th All-American in 1967. Today Canada remains active in various communities across the nation and continues to send participants to Akron.

Germany

Germany, the most active member of the international Derby community, began races in 1949 in what was then the US-occupation zone of Germany and Berlin. Its national sponsor was Adam Opel Automobile Works, which took over from US Armed Forces in 1951,[121] and supplied the official wheels used on the cars. Over the next ten years this led to 214 communities sending local champs to the German Nationals, its overall champion representing Germany at the All-American in Akron. Derby remains active in Germany.

Rules

One of Derby's first rules was that the car had to be "boy-built," without the assistance of an adult.[122] This was seldom the case as most boys did require some help simply because they lacked the skills to perform such a feat, acquiring them eventually as the car was constructed while working with an adult.[123] In the early days a boy was allowed assistance from a friend or other individual under the age of sixteen.[122] To guarantee that boys strictly obeyed the rule, pre-race inspection of the car would have judges randomly ask that he demonstrate his knowledge of its construction if there was doubt about who actually built it.[124] The rules also stipulated that the car must be driven by the boy that built it,[125] though in the event that he came down with an illness or injury and was therefore unable to race, he was permitted to name a substitute driver to go in his place.[126]

Race contestants at the local level were divided into two classes based on age: 9-12 raced as class B, 13-15 as class A. Each class declared a winner, who then raced each other in the final. That winner would be declared the overall Champion and become eligible to compete at the All-American in Akron as a representative of their home town. The class distinctions was replaced eventually by the three official divisions.

At Derby's inaugural race in 1934 as many as five raced at once in a single heat,[127] but this ended for safety reasons with the introduction of lanes. For decades cars raced in two or three lanes in single elimination heats, though double elimination races were being held as early as the late Fifties.[lower-alpha 18] With Derby Downs' mandate to level the competitive playing field following the '73 scandal, the 'double-elimination timer swap' became more commonplace, which today is standard practice.

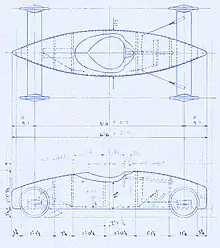

Construction

Derby regulations regarding the construction of racers played an integral role in their design, since cars had to comply with size and weight restrictions. Excluding wheels, axles and assembly hardware, all cars were to be made of wood only.[129] The maximum weight allowance was 250 lb (110 kg) for both car and driver (verified during a weigh-in prior to the race),[130] the overall length no more than 80 inches (200 centimetres), a wheelbase no less than 40 inches (100 centimetres), height not to exceed 30 inches (76 centimetres) and a wheel tread of between 30 inches (76 centimetres) and 36 inches (91 centimetres). The front axle was to be mounted on a single kingpin, and directional control governed by steel cables, a single steering column and wheel.[129] No ropes were allowed.[131] The brake was to be a friction or drag type, usually an armature through the floor that was activated by a foot pedal.[129] Wheels were to be the solid rubber type, not pneumatic, and measure no more than 12 inches (30 centimetres) in diameter, a limit that began in 1937.[131] Finally the driver was to be seated upright, though the practice was to crouch forward to minimize wind resistance.[132] Pre-race inspections verified that the car was well constructed according to strict observance of the rules, and safe to drive.

Restrictions

As governance increased and each year's Official Rules Book was updated, restrictions were implemented to maintain safety. Windscreens were popular design features used since 1934 that helped improve streamlining and thus overall speed, so to limit that they were banned in 1948.[107] They were permitted again in 1976 when they could be fitted on the new Junior-Division racers, but were dropped a year later. Between 2004 and 2014 they re-emerged at Ultimate Speed Challenge races, but have since been banned outright, no longer being permitted at any sanctioned Soap Box Derby race. In 1953 use of vertical-mounted steering columns was cut from the rule book,[107] allowing horizontal columns only, though today's modern kits all run with standardized, pre-fabricated vertical steering columns. In 1965 lead and steel were permitted in the construction of the car,[107] which was an asset in being able to add weight.

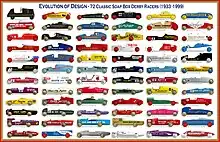

Car design

Design and construction of a Soap Box Derby car usually reflected the skills of the kid that built it, and as time passed each iteration with each new generation benefited from the previous on how a car would look. Before the introduction of kit cars in 1976, all cars were one-of-a kind creations, some looking outlandishly unique in their experimentation with form and function. Like any evolutionary process (pictured), if innovations were successful at the track they were passed on.

Sit-up cars

The majority of Soap Box Derby cars were—and remain—piloted by occupants in the sit-up position, and before 1964 was the only method allowed by the rules. Having not yet acquired the skills, boys usually learned as they went, building simple-to-construct, boxy designs—plywood or metal skin, even fabric, over a bulkhead/floorboard framework. As cars became less boxy and more curvaceous, other techniques were used to smooth out the body lines such as papier-mâché and chicken wire, which were among the many options suggested in the Official Rules Book. Construction of this type produced cars that performed well at races including the All-American, with some taking World Champion.

Examples of basic sit-ups that won in Akron are Derwin Cooper[lower-alpha 19] of Williamsport, PA who took the All-American in 1951, and Harold "Bo" Conrad[lower-alpha 20] from Duluth, MN who did the same in 1963.

Laminate cars

Boys learned to build more sophisticated racers that took aerodynamics into consideration, with the result being more streamlined designs. To achieve this the more skillful entries were made from laminate construction, sandwiching multiple layers of lumber laid horizontally or vertically and held together with fasteners or glue. The intent was to create a sturdy hollow shell in the shape a car,[133] the hollow cavity meant to accommodate the driver and various control mechanisms like the brake and steering. Once the glue had cured the outside of the shell had to be hewn into a more precise aerodynamic shape, using a hand plane or saw, then sanded smooth until the final form was achieved. With floorboards as thick as four inches, these cars ended up being considerably heavy, which was a useful advantage when smaller drivers needed the additional weight.[134] Though time-consuming it was a technique used successfully by skilled builders, but "next to impossible," as stated by Myron Scott in 1950,[135] for most boys. Derby Downs felt that its use placed an unfair advantage over other kids building the more common, boxy designs, so in 1950 banned its use. The following year the rule was rescinded,[136] and laminates continued being built as late as 1970.[137]

Examples of laminate construction are found in cars piloted by Thomas Fisher[lower-alpha 21] of Detroit, MI who won the All-American in 1940, Garland Ross, Jr.(pictured) of Muncie, IN who raced as a class B entry from 1949 to 1951, Donald Klepsch[lower-alpha 22] of Detroit, MI who won his local in 1949, and William Smith who took the Mobile, AL championship in 1964.[138]

Sight grooves and other Sixties innovations

Peculiar innovations appearing from the late-Fifties to the late-Sixties were cars fitted with clefts (pictured) or depressions running axially along the fore-deck, called 'sight-grooves',[lower-alpha 23] through which drivers could see ahead while slumped low in the cockpit. Other innovations saw the front axles being placed further aft in an attempt to place as much weight of the car rearward,[139] meaning as high up the hill from the finish line, to gain even a hundredth of a second advantage.[140][141] 1967 World Champion Ken Cline's low-profile racer, called the "Grasshopper",[lower-alpha 24] was the first World Champion with a car configured in this way. Cockpit tonneau covers were also being added to enclose a larger boy's back and shoulders, which usually protruded slightly outside the car body,[132] in an attempt to improve aerodynamics. With boys that raced for more than one year and began to outgrow their cars, side blisters would sometimes be fitted to accommodate shoulders or elbows that were becoming cramped. An unusual innovation came in 1968 with "shotgun steering," a design solution in response to a regulation stipulating that the steering column be situated 12 inches (300 mm) above the floor of the car. Many cars by then were being built lower than that, so the column had to be placed above and outside the car body, which ended up looking like a machine gun on a WWI fighter, and thus its name.[80] 1970 World Champion Sam Gupton's car[lower-alpha 25] had this design, but its use was banned after 1971.[107]

Lay-down cars

In 1964 the first lay-back or lay-down designs were appearing on the track,[107] this to improve performance by minimizing aerodynamic drag, and by the early Seventies had become the status-quo[80] for the most competitive cars, with 1969 being the first year that a lay-down design won the World Championship, piloted by Steve Souter[lower-alpha 26] of Midland, Texas.[142][143]

Stick cars

With the lay-downs came composite materials being incorporated into their construction, quite similar to wooden strip-built canoes laminated with fiberglass, called "stick car" construction. Though a challenge to undertake because of the complex curvature of the body shell, rounded bottom and headrest fairing, this technique became quite popular with experienced build-teams wanting to create small aerodynamic body shells that snugly enclosed the driver. Beginning in the Seventies[80] it was used almost exclusively to build the Senior and later Masters Division racers, and is still being used today to construct Legacy Division entries[144] at the All-American, praised for its emphasis on individuality,[145] innovation and creativity.

Examples of stick-cars are found in those piloted by Craig Kitchen[lower-alpha 27] from Akron, OH who was crowned World Champion in 1979, and Amanda Baker (pictured) who won the Akron (Metro), OH Masters Championship in 1991.

Kit cars

Wood kits

Kits debuted with the introduction of Junior Division in 1976 when Novar Electronics became the new sponsor. Purchased from the AASBD, they came with instructions and hardware only, with the builder supplying their own construction material, which was wood. This gave kids an easier way to construct a car, a "back-to-basics"[108] initiative that held firm to Derby Down's "kid-built" rule while benefiting financially from their sale. They retailed for $36.95.[146][109] Measurement remained roughly the same, with an overall length of 80 inches (200 centimetres). Unlike previous racers, the axles were kept exposed—without aerodynamic airfoils—and came with stabilizer braces or radius rods for the rear axle. The kit instructions offered several body designs from which to choose, but the general configuration was a flat-top car with a teardrop-shaped floor board, to which were affixed squared wooden bulkheads enclosed in a plywood skin. A standardized steering wheel was included in the kit. Windscreens were also permitted in 1976 on the kits only, but were discontinued the following year.

Examples of wood kits are racers piloted by Suzanne Miller (pictured) who won the Flint, MI Fall Junior Rally Championship in 1976, and Phil Raber[lower-alpha 28] who was the first Junior World Champion in a kit car the same year.

Fiberglass shell kits

In 1981 the first fiber glass "shell" kits arrived, which were complete pre-fabricated cars that required assembly only and, according to its designer Ken Cline, could be performed by a kid in as little as four hours.[2][147] Examples are Carol Ann Sullivan[lower-alpha 29] of Rochester, NH, who won the Junior World Championship in 1982 in a fiber glass kit, and Danielle DelFarraro[lower-alpha 30] of Akron (Suburban), OH, who took the Kit Car World Championship in 1993.

In 1992 the first shell kits were renamed Stock, followed in 1995 by the debut of the Super Stock Division car, a two-piece fiber glass shell of a completely new design replacing the previous Kit Car Division design. The final kit intended for the Masters Division, the "Scottie," debuted in 1999 as a full lay-down design with flat bottom and headrest fairing. The three official kits, Stock, Super Stock and Masters have remained official issue since then.

Masters sit-ups

From 1992 to 1998 many Masters Division competitors were dominating on the track with cars build in the traditional sit-up configuration,[148] which up to this point saw only lay-down cars as Masters entries. Prior to this the last sit-up that won the All-American was Branch Lew in 1968.[lower-alpha 31] Bonnie Thornton[lower-alpha 32] of Las Vegas, NV was the first Masters World Champion in a sit-up car in 1992, and James Marsh[lower-alpha 33] of Cleveland, OH was the last in 1998 and last to ever win in a sit-up as of 2023. Danielle DelFarraro[lower-alpha 34] of Akron, OH, who took the Masters World Championship in 1994 in a sit-up car, was the first back-to-back winner at the All-American after her 1993 world title in the Kit Division.[2]

Car dimensions

| Year | Car type | Overall length (max.), incl. wheels | Overall width (max.) | Overall height (max.) | Wheelbase (min.) from center of each spindle | Ground clearance (min.) incl. break pad | Weight of car and driver (max.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1934 | Sit-up | none specified | 42 inches (110 centimetres) | 34 inches (86 centimetres) | none specified | none specified | 250 pounds (110 kilograms) |

| 1937-1971 | Sit-up | 80 inches (200 centimetres) | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 24 inches (61 centimetres) | 48 inches (120 centimetres) | 3 inches (7.6 centimetres) | 250 pounds (110 kilograms) |

| 1964-1971 | Laydown | 80 inches (200 centimetres) | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 24 inches (61 centimetres) | 48 inches (120 centimetres) | 3 inches (7.6 centimetres) | 250 pounds (110 kilograms) |

| 1972-1998 | Laydown/Senior/Masters | 84 inches (210 centimetres)[149] | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 28 inches (71 centimetres)[149] | 65 inches (170 centimetres)[150] | 3 inches (7.6 centimetres)[150] | 250 pounds (110 kilograms) |

| 1976-1987 | Junior (wood kit) | 80 inches (200 centimetres)[150] | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 14 inches (36 centimetres)[149] | 65 inches (170 centimetres)[150] | 3 inches (7.6 centimetres) | [lower-alpha 35] |

| 1988-1994 | Kit Car (fiber glass shell) | 80 inches (200 centimetres)[149] | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 14 inches (36 centimetres)[149] | 65 inches (170 centimetres)[150] | 3⅝ inches (9.2 centimeters)[150] | [lower-alpha 36] |

| 1992-present | Stock (fiber glass shell) | 75¹⁄₁₆ inches (191 centimeters)[114] | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 15⅝ inches (40 centimeters) | 75¹⁄₁₆ inches (191 centimeters) | 3¹⁄₁₆ inches (7.6 centimeters) | 200 pounds (91 kilograms)[151] |

| 1995-present | Super Stock (fiber glass shell) | 75¹⁄₁₆ inches (191 centimeters)[114] | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 17¹⁄₁₆ inches (43 centimeters) | 75¹⁄₁₆ inches (191 centimeters) | 3¹⁄₁₆ inches (7.6 centimeters) | 230 pounds (100 kilograms)[151] |

| 1999-present | Masters (fiber glass shell) | 84¹⁄₁₆ inches (214 centimeters) | 40 inches (100 centimetres) | 17¹⁄₁₆ inches (43 centimeters) | 65 inches (170 centimetres) | 3¹⁄₁₆ inches (7.6 centimeters) | 255 pounds (116 kilograms)[151] |

Suspension

In the first years of Derby, a car's running gear (wheels, axles and suspension) ran the gamut with whatever a boy could cobble together, however rules were quickly implemented soon after to ensure a driver's safe control of his vehicle. By the late 1930s most cars had axles running through the car body rather than underneath, bolted to the topside of the floorboard. Flexibility of the axle bar helped dampen vibrations from the effects of imperfections on the track's surface like cracks, and counter undulations of the pavement. Wooden axletrees fitted over the axles were also permitted to act as aerodynamic airfoils that streamlined the car as well as spread the car's weight evenly over the axle's length. A variation on this was the "Akron Four-Point Suspension,"[152] where the axletrees would concentrate the car's weight at the end of the axles, alleviating their tendency to bow in the middle while under load. Axles could also be pre-bowed or arced to counter this, with the ends bent downward slightly, making the wheels camber outward at the top (positive camber). When the driver's weight was added the arc would flatten, straightening the wheels so they would sit perpendicular to the ground.[153]

More complex suspension designs that were suggested in the Official Rules Book were the 'rubber-ball suspension,' using a ball mounted atop the front axle as a spring cushion, and the 'springboard suspension,' where a diving-board-type device fitted in much the same way yielded similar results.[129] 1969 Sheboygan, WI Champion Michael Benishek, 15, used a coil-type suspension of his own design on both axles,[154] and was awarded Best-Innovation in the technical category along with his competitive win.[155] A unique suspension was found on 1979 Hamilton, OH Senior Champion Stuart Paul's car (pictured), winning the Best Design Award when he competed at the 42nd All-American.[156] His suspension comprised torsion bars fitted transversely through the car body, with trailing arms connected to a free-floating real axle that ran underneath. That year the rules stipulated that axles remain exposed on the Senior Division cars like they were on the Juniors. In response, builders installed taught wires between the nose of the car and the front wheels, called "kite steering" (pictured) to improve aerodynamics that were lost when airfoils over the axles were disallowed.

To this day the tightness settings of the fasteners between the axles and floorboard continue to be experimented with in various combinations to achieve maximum performance of the car. These include tightening the fasteners so they allow no movement whatsoever (called 'solid'), a slight amount of play ('tight') or free movement ('loose').[157]

Wheels

Wheel history

.jpg.webp)

The first years of the Derby saw any sort of running gear (wheels, bearings and axles) that a boy could get his hands on in order to complete in his car, since rules did not stipulate restrictions before 1937.

Pneumatic steel wheel (1936)

In 1936 wheels, bearing and axles were the first components of the car to become standardized with the introduction of the Goodrich Silvertown steel wheel. Purchased as a set, the two-part bolted wheels came with ball-type bearings and dustcaps and were fitted with a pneumatic tire measuring 15 inches (38 centimetres) x 1.75 inches (4.4 centimetres).[158] Though they were not required on the car to compete—as many boys still used wagon or baby-carriage wheels of various dimensions and styles,[159] they were used successfully by Herbert Muench[lower-alpha 37] of St. Louis, MO, who won the 1936 World Championship.

Riveted steel wheels (1937-1941)

In 1937 the official rule book stipulated a limit on wheel size of no more than 12 inches (30 centimetres)—a standard still used to this day—and a requirement that the tire be solid, not pneumatic. In compliance Goodrich Silvertown introduced Derby's first official-issue wheel,[107] made available for sale to within the $4-$6.00 budget set by Derby officials.[131] Like the previous year they comprised two steel halves—this time riveted together, soon to be replaced by welds—and came in a kit that included axles measuring 9⁄16 inch (14 millimetres). Wheel-sets were often in short supply in the early years,[33] and many suppliers took advantage of this by advertising after-market "Derby-type" wheels for sale in newspapers at a cheaper price, or to fill the gap when official issue were unavailable.

Official Soap Box Derby Tire red steel wheel (1951-1981)

In 1946 a new wheel, the Firestone Champion, was introduced that measured the same 12" diameter and was painted yellow with green dust cap. The following year they were painted gold, with the dust caps being dropped. In 1948 the popular red wheel was introduced, and by 1950 the rules stated that all cars had to use them, with nothing prior to 1948 being allowed.[160] In 1951 it was re-branded the "Official Soap Box Derby Tire", becoming the official issue[2] at all Derby events until 1981.

Z-glas plastic wheel (1982-2022)

In 1981 a new plastic 12¼ inch (31.1 centimeter) wheel was introduced, the white Z-Glas, developed by the AASBD technical organization and Derby's national sponsor Novar Electronic Corporation. Made of high-density linear polyethylene with a polyurethane tire, it was discovered to have structural problems, with reports of failure on the track, and was felt at the time that the issue was with the design and not the plastic.[161] Later research kept the design but tested twenty different types of plastics, settling on Dupont Zytel, made of 43% fiber glass filled nylon[80] and, according to Novar's James Ott, the "strongest plastic made." The tire was also of a higher-traction urethane compound. It required assembly of the two hubs, then addition of the tread.[162]

Replacing the steel wheel was done to offset its high cost, which was priced at $80.00 a set, while the new plastic issue would be $44.00. Because the wheel hubs were cast rather then pressed steel plate they were discovered to be more uniform, making wheel calibration of a set much less time consuming due to their limited variation. After the wheel was deemed safe it was released for sale for the 1992 race season,[163] and used successfully for forty-one years.

UniGrip one-piece wheel (2023- )

In 2023 the Z-glas was replaced by new the UniGrip, a black plastic, all-in-one-piece molded wheel and tire measuring the standard 12 inches (30 centimetres). The hubs of the new wheel are made of fiber-reinforced Nylon resin, similar to the wheel it replaces. The tread is made of thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU). “Molding of the one-piece hub-and-tread wheel eliminates the possibilities of variations by manual assembly during the production process, thereby increasing the consistency and stability of the end product,” said Bret Treier, board chairman of the Soap Box Derby. The wheel debuted at the 83rd All-American in July, 2023, and are priced at $225.00 for a set.[162]

Wheel performance

It was quickly understood that the way to victory relied largely on the wheels,[164] and several clever means, some legal, some not, were used to exploit this. Wheel and axle sets came new out of the box when purchased, and competitors quickly learned ways to break in the bearings to make them roll smoothly, or drill small holes in the metal fascia to balance a wheel out. Various lubricants were also experimented with, and other more interesting ways of improving performance involved the rubbing of dry ice on the rubber tire to harden it and thus lower its rolling resistance. Derby Downs quickly identified these techniques, accepting some but banning others.

Commemorative Championship wheels

.jpg.webp)

In 1958 Derby Downs began issuing commemorative Championship wheels (pictured) at the All-American, meaning every car had their original wheels swapped with a brand new set,[165] to "eliminate any type of hedging."[166] This practice continued until 1972, with each year's wheel having a unique color—gold (1958), silver (1959), robin-egg (1960), blue (1961), silver (1962-25th anniversary) and gold (1962-1972)—with matching water-slide decals on the obverse and reverse side, each year bearing a unique commemorative design. When Chevrolet dropped its sponsorship in 1972, the wheel continued to be painted gold but no longer had the decal. In 1982 the decals returned, this time on the obverse side only of the new Z-glas wheel, and again with a design unique to a particular year, but ended in 2002. Further commemorative wheels were issued at the 70th (2007) and 75th (2012) All-American.

Wheel swaps

To make things as fair as possible for racers,[167] i.e. putting "the fate of the race in the driver's hands,"[168] the practice of wheel swapping continues to this day in concert with lane swapping in double-elimination races.[169][170] Wheel swaps involve two competitors each selecting two wheels from their opponents car and having them put on their own, called a two-wheel "swap-off,"[130] eliminating the advantage of any one car having the better wheels. The initiative has received criticism for making races take too long.[171]

Modern Derby

Using standardized wheels with precision ball bearings, modern gravity-powered racers start at a ramp on top of a hill, attaining speeds of up to 35 miles per hour. Rally races and qualifying races in cities around the world use advanced timing systems that measure the time difference between the competing cars to the thousandth of a second to determine the winner of a heat. Each heat of a race lasts less than 30 seconds. Most races are double elimination races in which a racer that loses a heat can work their way through the Challenger's Bracket in an attempt to win the overall race. The annual World Championship race in Akron, however, is a single elimination race which uses overhead photography, triggered by a timing system, to determine the winner of each heat. Approximately 500 racers compete in two or three heats to determine a World Champion in each divisions.

There are three racing divisions in most locals and at the All-American competition.[107] The Stock division is designed to give the first-time builder a learning experience. Boys and girls, ages 7 through 13, compete in simplified cars built from kits purchased from the All-American. These kits assist the Derby novice by providing a step-by-step layout for construction of a basic lean forward style car. The Super Stock Car division, ages 9 through 18, gives the competitor an opportunity to expand their knowledge and build a more advanced model. Both of these beginner levels make use of kits and shells available from the All-American. These entry levels of racing are popular in race communities across the country, as youngsters are exposed to the Derby program for the first time. The Masters division offers boys and girls, ages 10 through 20, an advanced class of racer in which to try their creativity and design skills. Masters entrants may purchase a Scottie Masters Kit with a fiberglass body from the All-American Soap Box Derby.[172]

In 2021, Johnny Buehler, from Warrensburg, Missouri, became at the time the youngest racer to win the All-American Soap Box Derby Local Stock Division. He was eight years old at the time of his win.[173]

Ultimate Speed Challenge

The Ultimate Speed Challenge is an All American Soap Box Derby sanctioned racing format that was developed in 2004 to preserve the tradition of innovation, creativity, and craftsmanship in the design of a gravity powered racing vehicle while generating intrigue, excitement, and engaging the audience at the annual All-American Soap Box Derby competition.[174] The goal of the event is to attract creative entries designed to reach speeds never before attainable on the historic Akron hill. The competition consists of three timed runs (one run in each lane), down Akron's 989-foot (301 m) hill. The car and team that achieve the fastest single run is declared the winner. The timed runs are completed during the All American Soap Box Derby race week.

The open rules of the Ultimate speed Challenge have led to a variety of interesting car designs.[175][176] Winning times have improved as wheel technology has advanced and the integration between the cars and wheels has improved via the use of wheel fairings. Wheels play a key role in a car's success in the race. Wheel optimization has included a trend towards a smaller diameter (to reduce inertial effects and aerodynamic drag), the use of custom rubber or urethane tires (to reduce rolling resistance), and the use of solvents to swell the tires (also reducing rolling resistance). There is some overlap in technology between this race and other gravity racing events, including the buggy races race at Carnegie Mellon University.[177]

In 2004, during the inaugural run of the Ultimate Speed Challenge, the fastest time was achieved by a car designed and built by the Pearson family, driven by Alicia Kimball, and utilizing high performance pneumatic tires. The winning time achieved on the 989-foot (301 m) track was 27.190 seconds.

Jerry Pearson returned to defend the title with driver Nicki Henry in the 2005 Ultimate Speed Challenge beating the 2004 record time and breaking the 27.00 second barrier with an elapsed time of 26.953 seconds. Second place went to the DC Derbaticians with a time of 27.085 while third went to Talon Racing of Florida with a time of 27.320.[178]

John Wargo, from California, put together the 2006 Ultimate Speed Challenge winning team with driver Jenny Rodway. Jenny set a new track record of 26.934 seconds. Jenny's record stood for 3 years as revisions to the track and ramps after the 2006 race caused winning times to rise in subsequent races. Team Pearson finished 2nd with a time of 26.999 seconds and team Thomas finished 3rd with a time of 27.065.[179]

Team Eliminator, composed of crew chief and designer Jack Barr and driver Lynnel McClellan, achieved victory with a time of 27.160 in the 70th (2007) All-American Soap Box Derby Ultimate Speed Challenge. Jenn Rodway finished 2nd with a time of 27.334 while Hilary Pearson finished 3rd with a time of 27.367.[180]

Jack Barr returned in 2008 with driver Krista Osborne for a repeat team win with a 27.009 second run. Crew chief Tom Schurr and driver Cory Schurr place second with a time of 27.023 while crew chief Mike Albertoni and driver Danielle Hughes were 3rd after posting a time of 27.072.[181]

In the 72nd (2009) AASBD Ultimate Speed Challenge, Derek Fitzgerald's Zero-Error Racing team, with driver Jamie Berndt, took advantage of a freshly paved track, and set a new record time of 26.924 seconds. Cory Schurr placed second with a time of 26.987. Laura Overmyer of clean sheet racing finished third with a time of 27.003.

In 2010, Mark Overmyer's Clean Sheet/Sigma Nu team (CSSN) and driver Jim Overmyer set the track record at 26.861 seconds in the first heat of the opening round. Several minutes later, driver Sheri Lazowski, also of CSSN, lowered the record to 26.844 seconds, resulting in victory by 0.005 seconds over 2nd-place finisher Jamie Berndt of Zero Error. Competition was tight in 2010, with the top 3 cars finishing within a span of 0.017 seconds.[174]

In 2011, advancements in wheel technology and car design, coupled with ideal track conditions, lead to significantly lower times in the Ultimate Speed Challenge. Driver Kayla Albertoni and crew chief Mike Albertoni broke the record in heat 2 or the opening round with a 26.765, taking 0.079 seconds off the 2010 record. One heat later, driver Jim Overmyer and crew chief Mark Estes of team CSSN racing lowered the record a further 0.133 with a 26.632 run. Jim improved to 26.613 in round 2 to secure 2nd place. In heat 5, of the opening round, driver Kristi Murphy and crew chief Pat Murphy secured 3rd place with a run of 26.677. In the next heat, driver Sheri Lazowski (pictured) and crew chief Mark Overmyer (of CSSN racing) took the victory with a blistering run of 26.585 seconds. Sheri's record time was 0.259 seconds under her 2010 record and 0.339 seconds below the 2009 record. Her improvement in 2011 is the largest year-to-year change in the record in the history of the AAUSC race.[183] By winning in both 2010 and 2011, Sheri became the first repeat USC winner.

In 2012, revised starting ramps and a re-sealed track with a softer road surface, led to significant increases in finishing times. The 2012 winner, Laura Overmyer of CSSN racing, with crew chief Mark Estes, posted a winning time of 26.655 seconds, 0.070 seconds slower than the track record set by her team the prior year. Kristi Murphy, of Zero Error racing, finished in 2nd with a time of 26.769, 0.114 seconds back. Jamie Berndt, also of Zero Error racing, finished in 3rd place with a time of 26.827. Competition was not as close as in recent years, with the top 3 cars covering a span of 0.172 seconds. This is roughly double the span in 2009 and 2011 and 10 times the span in 2010. The 2012 results mark the 3rd consecutive win by CSSN racing and the 4th consecutive win by wheel expert Duane Delaney.[184][185]

The 2013 race was run under wet conditions which necessitated a format change. Each car was given a single run from lane 2 to determine the winner. The running order was randomly determined. CSSN Racing's Anne Taylor with crew chief Jerry Pearson won with a time of 26.929. Jillian Brinberg and crew chief Mark Estes, also of CSSN Racing, finished 2nd with a time of 26.978. Catherine Carney with crew chief Lee Carney finished 3rd with a time of 27.162.[186]

In 2014, CSSN's Anne Taylor with crew chief Jerry Pearson won with a time of 26.613. Anne's time improves on the prior best time for the new gate configuration but falls short of the 2011 record. This marks Anne's 2nd consecutive win and the 5th consecutive win for CSSN racing in this event. CSSN's Tucker McClaran with crew chief Mark Estes finished second with a time of 26.667. Catherine Carney with crew chief Lee Carney finished 3rd with a time of 26.750.

Derby Heritage