IntroductionA star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Sirius Photo credit: NASA and ESA

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. With a visual apparent magnitude of −1.46, it is almost twice as bright as Canopus, the next brightest star. The name "Sirius" is derived from the Ancient Greek Seirios ("scorcher"), possibly because the star's appearance was associated with summer. The star has the Bayer designation α Canis Majoris (α CMa, or Alpha Canis Majoris). What the naked eye perceives as a single star is actually a binary star system, consisting of a white main sequence star of spectral type A1V, termed Sirius A, and a faint white dwarf companion of spectral type DA2, termed Sirius B. Sirius appears bright due to both its intrinsic luminosity and its closeness to the Earth. At a distance of 2.6 parsecs(8.6 ly), the Sirius system is one of our near neighbors. Sirius A is about twice as massive as the Sun and has an absolute visual magnitude of 1.42. It is 25 times more luminous than the Sun but has a significantly lower luminosity than other bright stars such as Canopus or Rigel. The system is between 200 and 300 million years old. It was originally composed of two bright bluish stars. The more massive of these, Sirius B, consumed its resources and became a red giant before shedding its outer layers and collapsing into its current state as a white dwarf around 120 million years ago. Selected article - Surface magnetic field of SU Aur (a young star of T Tauri type), reconstructed by means of Zeeman-Doppler imaging Photo credit: user:Pascalou petit

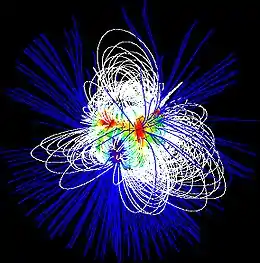

A stellar magnetic field is a magnetic field generated by the motion of conductive plasma inside a star. This motion is created through convection, which is a form of energy transport involving the physical movement of material. A localized magnetic field exerts a force on the plasma, effectively increasing the pressure without a comparable gain in density. As a result the magnetized region rises relative to the remainder of the plasma, until it reaches the star's photosphere. This creates starspots on the surface, and the related phenomenon of coronal loops. The magnetic field of a star can be measured by means of the Zeeman effect. Normally the atoms in a star's atmosphere will absorb certain frequencies of energy in the electromagnetic spectrum, producing characteristic dark absorption lines in the spectrum. When the atoms are within a magnetic field, however, these lines become split into multiple, closely spaced lines. The energy also becomes polarized with an orientation that depends on orientation of the magnetic field. Thus the strength and direction of the star's magnetic field can be determined by examination of the Zeeman effect lines. A star with a magnetic field will generate a magnetosphere that extends outward into the surrounding space. Field lines from this field originate at one magnetic pole on the star then end at the other pole, forming a closed loop. The magnetosphere contains charged particles that are trapped from the stellar wind, which then move along these field lines. As the star rotates, the magnetosphere rotates with it, dragging along the charged particles. Selected image - Sunspots Photo credit: NASA/TRACE

Sunspots are temporary phenomena on the surface of the Sun (the photosphere) that appear visibly as dark spots compared to surrounding regions. They are caused by intense magnetic activity, which inhibits convection, forming areas of reduced surface temperature. Although they are at temperatures of roughly 3,000–4,500 K, the contrast with the surrounding material at about 5,780 K leaves them clearly visible as dark spots, as the intensity of a heated black body (closely approximated by the photosphere) is a function of T (temperature) to the fourth power. If the sunspot were isolated from the surrounding photosphere it would be brighter than an electric arc. Sunspots expand and contract as they move across the surface of the sun and can be as large as 80,000 km (50,000 miles) in diameter, making the larger ones visible from Earth without the aid of a telescope. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Stars Stars by luminosity class Stars by metallicity Stars by spectral type Stars by type Stars with proper names Lists of stars Star types Astronomical catalogues of stars Star atlases Coats of arms with stars Star symbols Stars in the Andromeda Galaxy Star clusters Fiction about stars Stellar groupings Hypothetical stars Star images Stellar dynamics Sun Star systems Wikipedia categories named after stars Star stubs Sun Atmospheric radiation Solar calendars Coats of arms with sunrays Coats of arms with suns Sun in culture Day Horizontal coordinate system Missions to the Sun Solar observatories Solar phenomena Solar alignment Solar eclipses Solar energy Sun tanning Sundials Sun stubs Galaxies Astronomical catalogues of galaxies Galaxies discovered by year Fiction about galaxies Galaxy clusters Galaxy filaments Galaxy superclusters Lists of galaxies Galaxy morphological types Active galaxies Barred galaxies Dark galaxies Dwarf galaxies Elliptical galaxies Field galaxies Hypothetical galaxies Galaxy images Interacting galaxies Irregular galaxies Lenticular galaxies Low surface brightness galaxies Overlapping galaxies Peculiar galaxies Polar-ring galaxies Protogalaxies Ring galaxies Seyfert galaxies Spiral galaxies Starburst galaxies Supermassive black holes Galaxy stubs Wikipedia categories named after galaxies Black holes Fiction about black holes Intermediate-mass black holes Stellar black holes Supermassive black holes White holes Supernovae Fiction about supernovae Historical supernovae Hypernovae Discoverers of supernovae Supernova remnants Selected biography -Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, FRS (/ˌtʃʌndrəˈʃeɪkɑːr/ ⓘ; Tamil: சுப்பிரமணியன் சந்திரசேகர்; October 19, 1910 – August 21, 1995) was an Indian-American astrophysicist who, with William A. Fowler, won the 1983 Nobel Prize for Physics for key discoveries that led to the currently accepted theory on the later evolutionary stages of massive stars. Chandrasekhar was the nephew of Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930. Chandrasekhar's most notable work was the astrophysical Chandrasekhar limit. The limit describes the maximum mass of a white dwarf star, ~ 1.44 solar mass, or equivalently, the minimum mass above which a star will ultimately collapse into a neutron star or black hole (following a supernova). The limit was first calculated by Chandrasekhar in 1930 during his maiden voyage from India to Cambridge, England, for his graduate studies. In 1999, the NASA named the third of its four "Great Observatories" after Chandrasekhar. The Chandra X-ray Observatory was launched and deployed by Space Shuttle Columbia on July 23, 1999. The Chandrasekhar number, an important dimensionless number of magnetohydrodynamics, is named after him. The asteroid 1958 Chandra is also named after Chandrasekhar. American astronomer Carl Sagan, who studied Mathematics under Chandrasekhar, at the University of Chicago, praised him in the book The Demon-Haunted World: "I discovered what true mathematical elegance is from Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar." From 1952 to 1971 Chandrasekhar also served as the editor of the Astrophysical Journal. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1983 for his studies on the physical processes important to the structure and evolution of stars. Chandrasekhar accepted this honor, but was upset that the citation mentioned only his earliest work, seeing it as a denigration of a lifetime's achievement. He shared it with William A. Fowler.

TopicsWikiProjects

More science WikiProjects...

Things to do

Related portalsMore science portals...

Associated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals

|