Penny J. White (born May 3, 1956) is an American attorney and former judge who served as a judge on Tennessee’s First Judicial Circuit, as a judge for the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals, and as a justice on the Tennessee Supreme Court.[1] Former Justice White was the second woman to serve on the Tennessee Supreme Court. White was removed from office in a judicial retention election in 1996 as the only justice to lose a retention election in Tennessee under the Tennessee Plan.[2] After her time in the judiciary, White served as a professor at the University of Tennessee College of Law until her retirement in 2022.[1]

Early life and education

Penny J. White was born in Kingston, TN on May 3rd, 1956.[3] White's father, Carmen White born in 1919, was an employee of Eastman Base Mountain Construction Company as an electrician by trade.[3] Her mother, Jean Bush White, graduated high school at age thirteen and was fully employed at the age of fourteen by Clinchfield Railroad.[3] When White was growing up, her mother worked as an architectural secretary.[3] White's maternal grandparents, Charles H. Bush and Ethel Bush, were farmers in Scott County located in southwest Virginia.[3] Her paternal grandfather, Herman Sevier White, owned and operated a county store in Greene County, TN.[3] White's paternal grandmother, Edda White, was a homemaker.[3]

White attended Sullivan County Southern Central School in Blountville, TN for high school.[3] During high school, White held an office in student government.[3] White graduated from Central in 1974.[3] White attended East Tennessee State University located in Johnson City, TN for her undergraduate education. At East Tennessee State University, White graduated summa cum laude in 1978 with a Bachelor of Science degree double majoring in political science and criminal justice and minoring in speech.[3] In 1981, White graduated from the University of Tennessee College of Law to receive her Doctor of Jurisprudence law degree.[4] In 1987, White received her Masters of Law degree (L.L.M.) from Georgetown University Law Center.[1]

Legal and judicial career

White engaged in the private practice of law in Johnson City, Tennessee, from 1981 to 1983 and from 1985 to 1990. From 1983 to 1985 she served as supervising attorney and clinical instructor in the Georgetown University Law Center Criminal Justice Clinic.[5][6]

Penny White impressed Justice Scalia and the Supreme Court when she appeared before them at the age of 32. The New Yorker article on Scalia note: "In a 1988 speech, Justice Harry Blackmun, who retired in 1994, recalled how Scalia had grilled a lawyer named Penny White, a thirty-two-year-old solo practitioner from Johnson City, Tennessee. He "picked on her and picked on her and picked on her, and she gave it back to him," Blackmun said. "Finally, at the end of the case we walked off, and Nino said the only thing he could say: 'Wasn't she good? Wasn't she good?' The rest of us were completely silent. We knew she was very good."[7]

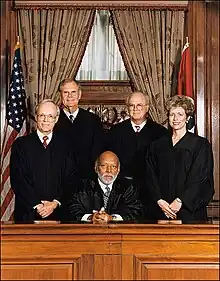

In 1990, she won election to a judgeship in Tennessee's First Judicial Circuit. In 1992 she left the circuit judgeship when Tennessee Governor Ned McWherter appointed her to the state's Court of Criminal Appeals. She served on that court until 1994, when McWherter selected her to fill a vacancy on the Tennessee Supreme Court.[5][6] She became the second woman ever to serve on the state's highest court.[8]

Vote on judicial retention

White became a subject of controversy in 1996 when she voted with the court majority in the 3-2 decision in the case of State v. Odom. That June 3, 1996 decision upheld a conviction for the rape and murder of an elderly woman, but overturned a death sentence.[5] It was the only death penalty decision that White ever participated in as a member of the state supreme court.[9]

As a recent appointee, White was the only member of the court who was subject to a retention vote in that year's election, and she was targeted for defeat by victims' rights advocates, the Tennessee Conservative Union, and death penalty proponents who opposed the decision.[5][8] White was restrained from campaigning on her own behalf by the judicial code of ethics, but her opponents "flooded the state" with materials urging her defeat.[5][8] One mailing urged voters to "Vote for capital punishment by voting NO on August 1 for Supreme Court Justice Penny White."[10] She was publicly opposed by Governor Don Sundquist and U.S. Senators Bill Frist and Fred Thompson, all Republicans.[5][8][11] As a result of the campaign against her, the "no" vote prevailed in the August 1, 1996, retention election, causing her to be removed from the court.[9] Only 19 percent of the state's voters voted in White's retention election.[12] Sundquist subsequently appointed Janice Holder to fill the seat she vacated.[5] Judge White's advocacy campaign, "People To Retain Justice White" raised over 10 times the funds of their counterparts, yet White was recalled during the election.

The defeat of White's judicial retention election was decried by people concerned that election of judges politicizes the judiciary, as well as by opponents of the death penalty. In a speech before the American Bar Association two days after White's defeat, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens stated that he considered the popular election of judges to be "profoundly unwise." He stated: "A campaign promise to be 'tough on crime' or 'enforce the death penalty' is evidence of bias that should disqualify the candidate from sitting in criminal cases."[9] The political nature of White's removal from the court has been likened to the earlier election defeat of California Chief Justice Rose Bird.[5]

When Adolpho A. Birch, who was chief justice of the court at the time of the State v. Odom decision, came up for a judicial retention vote in 1998, death penalty supporters campaigned for his removal. However, he was the beneficiary of a public awareness campaign on the importance of judicial retention elections that was mounted by the state's bar association, Farm Bureau, and League of Women Voters in Tennessee, and he retained his seat with 54 percent of the vote.[5][12]

Law school faculty career

After leaving the state supreme court, White held one-year law school visiting professorships at Washington and Lee University (1997–1998), West Virginia University (1998–1999), and the University of Denver (1999–2000).[6] In 2000, she joined the faculty of the University of Tennessee College of Law, where she was the Elvin E. Overton Distinguished Professor of Law and directs the Center for Advocacy and Legal Clinic.[13] The courses White undertook in professing included pretrial litigation, evidence, trial practice, and negotiation in addition to overseeing clinical programs and externship programs. White extends her passion for capital punishment jurisprudence and ethics through giving lectures across the United States at various legal and judicial education programs.

Recognition

- University of Tennessee, SEC Faculty Achievement Award (2019-2020)[4]

- Harold C. Warner Outstanding Teaching Award, University of Tennessee College of Law (2018)[4]

- Governors' Award, Knoxville Bar Association (2017) which is the highest award given by the Knoxville Bar Association Board of Governors[4]

- Bass, Berry & Sims Faculty Award, University of Tennessee College of Law (2016)[4]

- Advancement of Justice Award, National Judicial College (2014)[4]

- University of Tennessee Jefferson Prize (2012)[4]

- University of Tennessee National Alumni Association Outstanding Teacher Award (2012)[4]

- 2012 Dicta Award for best published article, Knoxville Bar Association[4]

- Harold C. Warner Outstanding Teaching Award, University of Tennessee College of Law (2010)[4]

- V. Robert Payant Award for Teaching Excellence, National Judicial College (2010)[4]

- Marilyn V. Yarborough Award for Writing Excellence, University of Tennessee College of Law (2009)[4]

- Carden Award for Outstanding Achievement in Scholarship, University of Tennessee College of Law (2008)[4]

- Carden Award for Outstanding Service to the Institution, University of Tennessee College of Law (2007)[4]

- Bass, Berry & Sims Award for Outstanding Service to the Bench and Bar, University of Tennessee College of Law (2006)[4]

- Forrest W. Lacey Award for Outstanding Contribution to the University of Tennessee College of Law Moot Court Program, 2013-2014; 2005-2006; 2002-2003; 2001-2002[4]

- Bernstein-Richie Award for Extraordinary Service to University of Tennessee Legal Clinic, 2002[4]

Published works

Law Review Articles

- The New Due Process: Fairness in a Fee-Driven State, 88 Tenn. L. Rev. 1025 (2022)[14]

- And Then There Were Yellow Roses, UTK Law Faculty Publications (Spring 2019)[15]

- The Other Costs of Judicial Elections, 67 DePaul L. Rev. 369 (Winter 2018)[16]

- If It “Aint” Broke, Break It: How the Tennessee General Assembly Dismantled and Destroyed Tennessee’s Unique Judicial System, 10 Tenn. J. Law & Policy 329 (2015)[17]

- A New Perspective on Judicial Disqualification: An Antidote to the Effects of the Decisions in White and Citizens United, 46 Ind. L. Rev. 103 (2013)[17]

- Relinquished Responsibilities, 123 Harvard L. Rev. 120 (2009)[18]

- Treated Differently in Life but not in Death: The Execution of the Mentally Retarded After Atkins v. Virginia, 76 Tenn. L. Rev. 685 (2009)[19]

- Using Judicial Performance Evaluations to Supplement Inappropriate Voter Cues and Enhance Judicial Legitimacy, 74 U. Mo. L. Rev. 635 (2009)[20]

- The Appeal to the Masses, 86 U. Denver L. Rev. 251 (2008)[17]

- A Response to Professor Fitzpatrick: The Rest of the Story, 75 Tenn. L. Rev. 501 (Spring 2008)[17]

- The Aftermath of Republican Party of Minnesota v. White, Pound Foundation (Summer 2007)[17]

- “He Said, She Said,” and Matters of Life and Death, 19 Regents U. L. Rev. 387(Fall 2006)[21]

- A Matter of Perspective, 3 University of North Carolina First Amendment L. Rev. 5 (Winter 2004)[17]

- Some Appeasement for Professor Tushnet, 71 Tenn. L. Rev. 275 (Winter 2004)

- “The Good, The Bad, and The (very, very) Ugly” (and its postscript, “A Fistful of Dollars”): Musings on White, 38 U. Richmond L. Rev. 626 (March 2004)[17]

- Symposium: Preserving the Legacy: A Tribute to Chief Justice Harry L. Carrico, One Who Exalted Judicial Independence, 38 U. Rich. L. Rev. 615 (March 2004)[17]

- Legal, Political, and Ethical Dilemmas to Applying International Human Rights Laws in State Courts, 71 U. Cinn. L. Rev. 937 (Spring 2003)[17]

- Mourning and Celebrating on Gideon’s Fortieth, 72 U. Missouri-Kansas City L. Rev. 515 (Winter 2003) Rescuing Confrontation, 54 S.C. L. Rev. 537 (Spring 2003)[17]

- Judging Judges: Securing Judicial Independence By Use of Judicial Performance Evaluations, 24 Fordham Urban Law Journal 1053 (February 2002)[22]

- Errors and Ethics: Dilemmas in Death, 29 Hofstra L. Rev. 1265 (Summer 2001)[17]

- A Response and Retort, 33 Conn. L. Rev. 899 (Spring 2001)[17]

- Newly Available, Not Newly Discovered, 2 J. of App. Prac. and Proc. 7 (Winter 2000)

- Can Lightning Strike Twice? Obligations of State Courts After Pulley v. Harris, 70 Col. L. Rev. 813 (Summer 1999)[17]

- Master, Justice, Chancellor Kent: His Legacy For Today’s Judges, 74 Chi-Kent L. Rev (1999)[17]

- If Justice Is For All, Who Are Its Constituents?, 64 Tenn. L. Rev. 259 (1997)[17]

- “It’s a Wonderful Life,” or Is It? America Without Judicial Independence, 27 U. Mem. L. Rev. 1 (1996), partial reprint in 80 Judicature 174 (Jan. - Feb. 1997)[17]

- Yesterday’s Vision, Tomorrow’s Challenge: Alternative Dispute Resolution in Tennessee, 26 U. Mem. L. Rev. 957 (1996)[17]

- A Survey of Tennessee Supreme Court Death Penalty Cases in the 1990s, 61 Tenn. L. Rev. 733 (1994)[23]

- A Noble Idea Whose Time Has Come, 18 Mem. State L. Rev. 223 (1988) (master’s thesis)[17]

Books

- Tennessee Capital Case Handbook (Tennessee Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers) (rev’d. edition 2014)[17]

- Tennessee Capital Case Handbook (Tennessee Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers) (2010)[17]

Chapters in Books

- Introduction to Gideon v. Wainwright, in Readings in Persuasion: Briefs that Changed the World (2012)[17]

- Tennessee’s New Abolitionists, Chapter 6, Judicial Independence and the Death Penalty (University of Tennessee Press) (2010)[17]

- Presiding Over a Capital Case: A Benchbook for Judges, Chapter 1, Capital Cases and Federal Constitutional Issues; Chapter 10, Federal Habeas Corpus (William J. Brunson, et al, eds., National Judicial College) (2009)[17]

- Introduction to Capital Litigation: Overview and History of Capital Jurisprudence in the United States Supreme Court, Chapter 1, Capital Litigation Improvement Initiative Benchbook for State Trial Judges (2009)[17]

- Review of State Death Sentenced by Federal Courts: The Impact of Federal Habeas Corpus on State Death[17]

- Penalty Cases, Chapter 10, Capital Litigation Improvement Initiative Benchbook for State Trial Judges (2009)[17]

- Judicial Independence and Capital Punishment in Tennessee, Chapter 6, Tennessee’s New Abolitionists: The Fight Against the Death Penalty in the Volunteer State (2009)[17]

- Several Chapters in Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties and Rights (Otis H. Stephens & John Scheb, eds.)(2006)[17]

- The Improvement of the Administration of Justice, Chapter 33, The Continuing Evolution of the Federal Rules of Evidence (7th ed. 2001)[17]

- Employee Rights From the Government Perspective: An Overview From the Practicing Attorney’s Viewpoint, in Communicating Employee Responsibilities and Rights (Osigweh ed., 1987)[17]

Publications for state court judges

- Tennessee’s Municipal Court Judges Benchbook (2004-2006)[17]

- Tennessee General Sessions Court Judges Benchbook (2002- 2005)[17]

- Post-Conviction Manual for Trial Judges (National Judicial College, University ofNevada 2001) Tennessee Trial Judges Benchbook (2000)[17]

- Sentencing Manual for State Court Judges, National Judicial College (1998-99)[17]

References

- 1 2 3 University of Tennessee. "Penny White". University of Tennessee. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- ↑ Vines, Georgiana. “Where Are They Now: Election Loss Led to Success in Academia for Former TN Justice Penny White.” Knoxville News Sentinel, September 6, 2014. https://archive.knoxnews.com/entertainment/life/where-are-they-now-election-loss-led-to-success-in-academia-for-former-tn-justice-penny-white-ep-596-354313321.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Penny J White, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=poJaoT87avU.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 “PENNY J. WHITE CV.” University of Tennessee, 2022. https://law.utk.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Penny-J.-White-Resume-Updated-August-2019.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 John R. Vile (2003), Great American judges: an encyclopedia, Pages 306-307.

- 1 2 3 Penny J. White curriculum vitae, University of Tennessee College of Law website, accessed April 20, 2011.

- ↑ Talbot, Margaret (28 March 2005). "Supreme Confidence". The New Yorker. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Colman McCarthy, Injustice Claims a Tennessee Judge, The Washington Post, November 26, 1996. Page C11.

- 1 2 3 Richard Carelli (Associated Press), "Does electing judges politicize the death penalty?" Published by the Daily Union (Junction City, Kansas), December 2, 1996.

- ↑ Ted Gottfried (2002), The death penalty: justice or legalized murder?. Twenty-First Century Books. Page 70.

- ↑ Bronson D. Bills, A Penny for the Court's Thoughts? The High Price of Judicial Elections Archived 2011-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, 3 Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy 29, Winter 2008.

- 1 2 Alfred P. Carlton, Jr., Individual States Tackle Issues Of Judicial Independence, As ABA Offers Support, ABA Now website (American Bar Association), accessed April 22, 2011.

- ↑ “Penny White.” University of Tennessee College of Law, https://law.utk.edu/directory/penny-white/. Accessed 12 Sept. 2023.

- ↑ Reynolds, Glenn Harlan, and Penny J. White. “The New Due Process: Fairness in a Fee-Driven State.” Tennessee Law Review 88, no. 1025 (February 22, 2022): 36. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4040335.

- ↑ White, Penny, "And Then There Were Yellow Roses" (2019). UTK Law Faculty Publications. 120. https://ir.law.utk.edu/utklaw_facpubs/120

- ↑ “PENNY J. WHITE CV.” University of Tennessee, 2022.https://law.utk.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Penny-J.-White-Resume-Updated-August-2019.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 “PENNY J. WHITE CV.” University of Tennessee, 2022.https://law.utk.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Penny-J.-White-Resume-Updated-August-2019.pdf

- ↑ White, Penny J. “Relinquished Responsibilities The Supreme Court, 2008 Term: Comment.” Harvard Law Review 123, no. 1 (2010 2009): 120–52. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/hlr123&i=122.

- ↑ White, Penny J. “Treated Differently in Life but Not in Death: The Execution of the Intellectually Disabled after Atkins v. Virginia Symposium.” Tennessee Law Review 76, no. 3 (2009 2008): 685–712. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/tenn76&i=693.

- ↑ White, Penny J. “Using Judicial Performance Evaluations to Supplement Inappropriate Voter Cues and Enhance Judicial Legitimacy Symposium: Mulling over the Missouri Plan: A Review of State Judicial Selection and Retention Systems: Retention Elections in a Merit-System Selection System: Balancing the Will of the Public with the Need for Judicial Independence and Accountability.” Missouri Law Review 74, no. 3 (2009): 635–66. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/molr74&i=641.

- ↑ White, Penny J. “He Said, She Said, and Issues of Life and Death: The Right to Confrontation at Capital Sentencing Proceedings.” Regent University Law Review 19, no. 2 (2007 2006): 387–428. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/regulr19&i=391.

- ↑ White, Penny J. “Judging Judges: Securing Judicial Independence by Use of Judicial Performance Evaluations Special Series: Judicial Independence.” Fordham Urban Law Journal 29, no. 3 (2002 2001): 1053–78. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/frdurb29&i=1069.

- ↑ White, Penny J. “A Survey of Tennessee Supreme Court Death Penalty Cases in the 1990s Symposium: The Law of the Land: Tennessee Constitutional Law.” Tennessee Law Review 61, no. 2 (1994 1993): 733–46. https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/tenn61&i=745.