| Provincia Pannonia | |

|---|---|

| 8 AD–433 AD | |

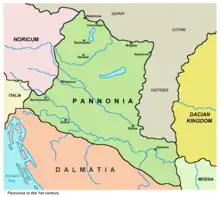

Province of Pannonia in the first century AD | |

| Capital | Carnuntum,[1] Sirmium,[2] Savaria,[3] Aquincum,[4] Poetovio[5] or Vindobona[6] |

| Demonym | Pannonian |

| History | |

| Historical era | Classical antiquity |

• Established via separation from Illyricum | 8 AD |

| 433 AD | |

Pannonia (/pəˈnoʊniə/, Latin: [panˈnɔnia]) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now western Hungary, western Slovakia, eastern Austria, northern Croatia, north-western Serbia, northern Slovenia, and northern Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Background

In the Early Iron Age, Transdanubia was inhabited by the Pannonians or Pannonii,[note 1] a collection of tribes subtype to the Illyrians, while the Great Hungarian Plain by peoples of Scythic culture. The Celts invaded in the Late Iron Age. Gallo-Roman historian Pompeius Trogus tells us that the Celts met with heavy resistance from the locals and couldn't overrun the southern part of Transdanubia. Some tribes advanced as far as Delphi, with the Scordisci settling in Syrmia (279 BC) upon forced to withdraw. The Celts founded many villages. Those that held prominent economic significance developed into oppida.[8]

Pannonia was connected to the Italian Peninsula by trade since the 2nd millennium BC. Amber from Jutland and East Prussia arrived to there through Transdanubia. Later in the 1st millennium BC, industrial products of the Veneti and Etruscans, and from the Este culture were brought here.[9] The Celtic invasion broke trade between the inhabitants of Italy and the Germanic peoples through Transdanubia. There was no big rupture with the inhabitants of Transdanubia, however. Aes signatum ingots were in use in Pannonia as long as the 1st century BC.[9] Independent tribes minted their own coins with the faces of their leaders. These were at first modeled on Macedonian, and later Roman currency.[8] For one and a half century prior to the Roman invasion, the Celts and the Romans were in stable trade relations. Roman merchants brought industrial products in exchange for slaves and raw materials.[10]

Upon the latter's withdrawal and settlement, the Dardani and the Scordisci both became strong powers who opposed each other. The Dardani ceaselessly raided Macedon and developed close ties to Rome.[11] Philip V, who was a vehement enemy of the Dardani, allied with the Scordisci and in 179 BC persuaded the Bastarnae to try subduing them to reach Italy. Despite Philip's defeat at the hands of the Romans in 197 BC and the failure of the Bastarnae, in this time the Dardani's power crumbled.[12] This was caused by the two-front pressing of the Macedonians and Scordisci. Finally, Perseus annihilated them, giving way to hundred years of Scordisci hegemony in the Balkans, to the terror of the new province of Macedonia.[13] Strabo says they expanded as far as Paeonia, Illyria and Thrace.[14]

Aquileia's foundation was the first step towards the takeover of Pannonia. The town functioned as the starting station of the Amber Road and the starting point of attacks in that direction.[15] The Scordisci, in alliance with the Dalmatae were in armed conflict with the Romans as early as 156 BC and 119 BC. In both wars, the Romans failed to take Siscia (now Sisak, Croatia), which laid in a key position.[16] After these setbacks, Rome turned instead towards Noricum which had both iron and silver mines.[15]

As part of a new Celtic migration wave at the end of the 2nd century BC, the Boii left Northern Italy and established themselves as an important power at the Danube.[17] According to the Posidonius's record of the Cimbri migration (preserved by Strabo), they were first repulsed by the Boii, then by the Scordisci, and then by the Taurisci towards the Helvetii. This describes the balance of power in the region.[18] In the early 1st century BC, the Dacians emerged as a new dominant power. While their hold on the area between the Danube and the Tisza was loose, they had considerable influence in the territories beyond.[19] In 88 BC, Scipio Asiaticus (consul 83 BC) defeated the Scordisci so badly that they retreated to the eastern part of Syrmia.[20] Taking advantage of this situation, the Dacian king Burebista vanquished them sometime between 65 and 50 BC, and subsequently the Boii and the Taurisci too. Thanks to the ebb of these entities, several local tribes regained their independence and influence.[21] In context of Mithridates VI Eupator's unfulfilled plan to invade Italy from the north (64 BC), the territory he was to cross is noted to have belonged to the Pannonians.[22] Immediately after Burebista's death (c. 44 BC), Dacia's kingdom dissolved too.[23]

Roman conquest

Through Tiberius Nero, then my stepson and legate, I brought under Roman authority Pannonian peoples which no Roman army had approached before I became princeps and advanced the boundaries of lIIyricum to the bank of the Danube.

Octavian maintained large armies to keep the balance with Mark Antony, so to put a better face on his activity, he pursued a foreign policy of expanding Roman dominions northward.[25] Pannonia was driven into conflict due to the support of the Dalmatae in their strife against Rome.[7] The tribes north of the Drava didn't participate in nor this, nor the subsequent fights.[15] In 35 BC, Octavian led a campaign against the Iapydes and the Pannonians,[26] in which he captured Siscia in a month-long siege.[27] A large part of the Sava valley thus came under occupation. This was in accordance with Caesar's plan not realized due to his assassination, but it appears Octavian didn't intend to use the newly acquired land as a base for an invasion of Dacia, instead wanting to establish closer contact with Dalmatia.[19]

In 16 BC, Augustus conquered the Kingdom of Noricum.[28] In 15 BC, the future-emperor Tiberius attacked the Scordisci[29] and forced them to become Rome's allies.[27] In 14 BC, the Pannonians rose up. Vipsanius Agrippa was sent to the region after another rebellion in 13 BC.[30] After his death the following year, the campaign was taken over by Tiberius,[31] who celebrated his triumph in 11 BC. The province of Illyricum was established between the Sava and the Adriatic Sea.[26] In 10 BC, Tiberius returned to quell a new uprising of the Pannonians and Dalmatae.[32] After winning in 9 BC, he sold the youth of the Breuci and Amantini as slaves in Italy[33] and held an ovation.[32] His operations between 12 and 9 BC included constant expeditions into territories north of the Drava and certainly brought the whole Transdanubia under Roman control even though there's no direct evidence to that.[34]

Pannonia was invaded by the Dacians in 10 BC. The Romans launched campaigns through the Danube in order to secure the very threatened new land. Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus's (consul 16 BC) operation in 1 AD extended as far as the Elbe. Locally more important was the offensive of Marcus Vinicius against the tribes east of the Danube Bend, showing an intent of "monopolizing" the Northern Transdanubian region politically.[27]

The last decade of the century saw the Marcomanni settling north of Pannonia. Augustus planned a two-sided attack on them, with one army approaching their territory from the Rhine and another one under Tiberius crossing the Danube at Carnuntum.[27] Before witnessing any result, Tiberius had to rush back in 6 AD and face a new uprising.[35] The Bellum Batonianum lasted for three years. The Breuci (under Bato the Breucian) and Daesitiates (under Bato the Daesitiate and Pinnes) took the leading role, while the tribes north of the Sava stayed out again. The insurgents attempted to invade Italy and Macedonia, but due to their lack of success they united to besiege Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia). There, Caecina Severus defeated the insurgents, who retreated into the Fruška gora Mountains.[36] He annihilated them the following year when they tried to intercept him on his way to join Tiberius at Siscia.[7] Tiberius initiated a scorched-earth policy against the rebels who destroyed their harvests left behind, pressuring most of them into surrender in 8 AD. Bato the Breucian delivered Pinnes to the Romans and became the vassal king of his tribe.[37] Augustus met Tiberius in Ariminum personally.[7] However, the revolt flared up once again as the Daesitiates captured and executed Bato the Breucian, and persuaded the tribesmen to continue the resistance.[38] Plautius Silvanus (consul 2 BC) reconquered them and ousted Bato the Daesitiate into the Dinaric Alps, where he laid down arms in 9 AD and went into exile in Ravenna.[7]

Roman rule

Consolidation and establishment of administration

Illyricum was divided into Dalmatia (initially called Illyricum Superius) and Pannonia (initially Illyricum Inferius) in 8 AD.[note 2][39]

According to Suetonius, with the Bellum Batonianum, Tiberius finally defeated all peoples between the Danube and the Adriatic Sea.[7] No Illyrian resistance is known after this, not due to the natives' compliance with the new status quo, but due to their extreme exhaustion.[40] The communities taking part in it were afterward relocated and organized into civitates under military supervision.[note 3][32]

The foremost objective of Rome in the region continued to be the conclusion of the barbarian conflicts.[41] Diplomacy was established with the Germanic peoples. Rome began to actively interfere in the politics of the Marcomanni to make their sympathizers kings.[15] Plautius Silvanus (praetor 24 AD) moved as many as 100,000 barbarians from Pannonia to Moesia. During the significant governorship of Tampius Flavianus, Roman currency began to circle in the Barbaricum and the first stage of the consolidation of the Central Danubian limes took place. Also, 50,000 barbarians may have been settled inside and the province's administration may have been organized.[41]

Under the Antonines

Due to the proximity of hostile barbarian tribes, many fortifications were built on the border and large number of legionaries and auxiliaries were stationed in the region.[42]

Some time between the years 102 and 107, between the first and second Dacian wars, Trajan divided the province into Pannonia Superior (western part with the capital Carnuntum), and Pannonia Inferior (eastern part with the capitals in Aquincum and Sirmium[43]). According to Ptolemy, these divisions were separated by a line drawn from Arrabona in the north to Servitium in the south; later, the boundary was placed further east. The whole country was sometimes called the Pannonias (Pannoniae).

The Sarmatians

The province of Pannonia was threatened from the east by the Scythic Sarmatians. During the conquest of Transdanubia, Sarmatian peoples, most notably the Iazyges occupied the Danube–Tisza Interfluve, vassallizing the Dacian-Celtic elements in the area and trading with both the Romans and other Celts. This was beneficial for the Roman Empire because the Sarmatians counterbalanced Dacia. Nonetheless, their looting campaigns through the frozen Danube[44] resulted in large amounts of soldiers being drawn to that segment of the border in the 180s. In the 190s, guard posts, bridgeheads, earth forts and later stone forts were constructed at Aquincum, Albertfalva, Nagytétény, Adony, Százhalombatta, Dunaújváros and other settlements.[45]

Marcomannic Wars

The one and a half century of relative peacefulness in the province was ended by an invasion of the Marcomanni, Quadi and Iazyges during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. The struggle was made even more difficult by the ravaging Antonine Plague, in which the emperor himself died at Vindobona, Pannonia Superior.[46] Marcus Aurelius constructed the limes.[47]

Crisis and stabilisation

After Marcus Aurelius, Commodus continued to fight along the limes, but governed the empire negligently. External attacks made possible Septimius Severus's ascension to the throne, who was governor of Pannonia Superior. Thanks to this soldier-emperor, peace returned for half a century. After the fall of the Severan dynasty, internal and external conflict restarted. The ambient barbarian peoples were able to penetrate in multiple parts of the border. In 260 Roxolani invaded the province.[47]

Administration

Pannonia Superior was under the consular legate, who had formerly administered the single province, and had three legions under his control. Pannonia Inferior was at first under a praetorian legate with a single legion as the garrison; after Marcus Aurelius, it was under a consular legate, but still with only one legion. The frontier on the Danube was protected by the establishment of the two colonies Aelia Mursia and Aelia Aquincum by Hadrian.

Under Diocletian, a fourfold division of the country was made:

- Pannonia Prima in the northwest, with its capital in Savaria, it included Pannonia Superior and the major part of Central Pannonia between the Raba and Drava,

- Pannonia Valeria in the northeast, with its capital in Sopianae, it comprised the remainder of Central Pannonia between the Raba, Drava and Danube,

- Pannonia Savia in the southwest, with its capital in Siscia,

- Pannonia Secunda in the southeast, with its capital in Sirmium

Diocletian also moved parts of today's Slovenia out of Pannonia and incorporated them in Noricum. In 324 AD, Constantine I enlarged the borders of Roman Pannonia to the east, annexing the plains of what is now eastern Hungary, northern Serbia and western Romania up to the limes that he created: the Devil's Dykes.

In the 4th-5th century, one of the dioceses of the Roman Empire was known as the Diocese of Pannonia. It had its capital in Sirmium and included all four provinces that were formed from historical Pannonia, as well as the provinces of Dalmatia, Noricum Mediterraneum and Noricum Ripense.

Pannonia in the 1st century

Pannonia in the 1st century Pannonia in the 2nd century

Pannonia in the 2nd century Pannonia in the 4th century

Pannonia in the 4th century Pannonia with Constantine I "limes" in 330 AD

Pannonia with Constantine I "limes" in 330 AD

Loss

In the 4th century, the Romans (especially under Valentinian I) fortified the villas and relocated barbarians to the border regions. In 358 they won a great victory over the Sarmatians, but raids didn't stop. In 401 the Visigoths fled to the province from the Huns, and the border guarding peoples fled to Italia from them, but were beaten by Uldin in exchange for the transferring of Eastern Pannonia. In 433 Rome completely handed over the territory to Attila for the subjugation of the Burgundians attacking Gaul.[48]

After Roman rule

During the Migration Period in the 5th century, some parts of Pannonia were ceded to the Huns in 433 by Flavius Aetius, the magister militum of the Western Roman Empire.[49] After the collapse of the Hunnic empire in 454, large numbers of Ostrogoths were settled by Emperor Marcian in the province as foederati. The Eastern Roman Empire controlled southern parts of Pannonia in the 6th century, during the reign of Justinian I. The Byzantine province of Pannonia with its capital at Sirmium was temporarily restored, but it included only a small southeastern part of historical Pannonia.

Afterwards, it was again invaded by the Avars in the 560s, and the Slavs, who first may settled c. 480s but became independent only from the 7th century. In 790s, it was invaded by the Franks, who used the name "Pannonia" to designate the newly formed frontier province, the March of Pannonia. The term Pannonia was also used for Slavic polity like Lower Pannonia that was vassal to the Frankish Empire.

Cities and auxiliary forts

The native settlements consisted of pagi (cantons) containing a number of vici (villages), the majority of the large towns being of Roman origin. The cities and towns in Pannonia were:

Now in Austria:

Now in Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Now in Croatia:

- Ad Novas (Zmajevac)

- Andautonia (Ščitarjevo)

- Aqua Viva (Petrijanec)

- Aquae Balisae (Daruvar)

- Certissa (Đakovo)

- Cibalae (Vinkovci)

- Cornacum (Sotin)

- Cuccium (Ilok)

- Iovia or Iovia Botivo (Ludbreg)

- Marsonia (Slavonski Brod)

- Mursa (Osijek)

- Siscia (Sisak)

- Teutoburgium (Dalj)

Now in Hungary:

- Ad Flexum (Mosonmagyaróvár)

- Ad Mures (Ács)

- Ad Statuas (Vaspuszta)

- Ad Statuas (Várdomb)

- Alisca (Szekszárd)

- Alta Ripa (Tolna)

- Aquincum (Óbuda, Budapest)

- Arrabona (Győr)

- Brigetio (Szőny)

- Caesariana (Baláca)

- Campona (Nagytétény)

- Cirpi (Dunabogdány)

- Contra-Aquincum (Budapest)

- Contra Constantiam (Dunakeszi)

- Gorsium-Herculia (Tác)

- Intercisa (Dunaújváros)

- Iovia (Szakcs)

- Lugio (Dunaszekcső)

- Lussonium (Dunakömlőd)

- Matrica (Százhalombatta)

- Morgentianae (Tüskevár (?))

- Mursella (Mórichida)

- Quadrata (Lébény)

- Sala (Zalalövő)

- Savaria (Szombathely)

- Scarbantia (Sopron)

- Solva (Esztergom)

- Sopianae (Pécs)

- Ulcisia Castra (Szentendre)

- Valcum (Fenékpuszta)

Now in Serbia:

- Acumincum (Stari Slankamen)

- Ad Herculae (Čortanovci)

- Bassianae (Donji Petrovci)

- Bononia (Banoštor)

- Burgenae (Novi Banovci)

- Cusum (Petrovaradin)

- Graio (Sremska Rača)

- Onagrinum (Begeč)

- Rittium (Surduk)

- Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica)

- Taurunum (Zemun)

Now in Slovakia:

Now in Slovenia:

Economy

The country was fairly productive, especially after the great forests had been cleared by Probus and Galerius. Before that time, timber had been one of its most important exports. Its chief agricultural products were oats and barley, from which the inhabitants brewed a kind of beer named sabaea. Vines and olive trees were little cultivated. Pannonia was also famous for its breed of hunting dogs. Although no mention is made of its mineral wealth by the ancients, it is probable that it contained iron and silver mines.

Slavery

Slavery held a less important role in Pannonia's economy than in earlier established provinces. Rich civilians had domestic slaves do the housework while soldiers who had been awarded with land had their slaves cultivate it. Slaves worked in workshops primarily in western cities for rich industrialist.[50] In Aquincum, they were freed in a short time.[44]

Religion

Pannonia had sanctuaries for Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, official deities of empire, and also for old Celtic deities. In Aquincum there was one for the mother goddess. The imperial cult was also present. In addition, Judaism and eastern mystery cults also appeared, the latter centered around Mithra, Isis, Anubis and Serapis.[44]

Christianity began to spread inside the province in the 2nd century. Its popularity didn't decrease even during the big persecutions in the late 3rd century. In the 4th century, basilicas and funeral chapels were built. We know of the Church of Saint Quirinus in Savaria and numerous early Christian memorials from Aquincum, Sopianae, Fenékpuszta, and Arian Christian ones from Csopak.[44]

Legacy

The ancient name Pannonia is retained in the modern term Pannonian plain.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Haywood, Anthony; Sieg, Caroline (2010). Vienna, Anthony Haywood, Caroline (CON) Sieg, Lonely Planet Vienna, 2010, page 21. ISBN 9781741790023.

- ↑ Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1835). "The third book of history: containing ancient history in connection with ancient geography, Samuel Griswold Goodrich, Jenks, Palmer, 1835, page 111".

- ↑ Lengyel, Alfonz; Radan, George T.; Barkóczi, László (1980). The Archaeology of Roman Pannonia, Alfonz Lengyel, George T. Radan, University Press of Kentucky, 1980, page 247. ISBN 9789630518864.

- ↑ Laszlovszky, J¢Zsef; Szab¢, P'ter (January 2003). People and nature in historical perspective, Péter Szabó, Central European University Press, 2003, page 144. ISBN 9789639241862.

- ↑ "Historical outlook: a journal for readers, students and teachers of history, Том 9, American Historical Association, National Board for Historical Service, National Council for the Social Studies, McKinley Publishing Company, 1918, page 194". 1918.

- ↑ Pierce, Edward M. (1869). "THE COTTAGE CYCLOPEDIA OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY, ED.M.PIERCE, 1869, page 915".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Barkóczi 1980, p. 89.

- 1 2 Trogmayer 1980, p. 81.

- 1 2 Alföldi 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 12.

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 12.

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 13.

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 14.

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 Barkóczi 1980, p. 90.

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 86; Mócsy 1974, p. 15, 16

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 86.

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 16.

- 1 2 Barkóczi 1980, p. 87.

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Tóth 1983, p. 19; Mócsy 1974, p. 18

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 87; Tóth 1983, p. 20; Mócsy 1974, p. 18, 19

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 87; Mócsy 1974, p. 18

- ↑ Mócsy 1974, p. 21.

- ↑ Wilkes 1992, p. 206.

- ↑ Boren 1977, p. 124.

- 1 2 Tóth 1983, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Barkóczi 1980, p. 88.

- ↑ Eck, Werner (2007). The Age of Augustus. Translated by Schneider, Deborah L. (Second ed.). Blackwell Publishing (now Wiley-Blackwell). p. 128.

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Tóth 1983, p. 20

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Tóth 1983, p. 20

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 88; Tóth 1983, p. 20

- 1 2 3 Tóth 1983, p. 21.

- ↑ Tóth 1983, p. 21; Wilkes 1992, p. 207; Mócsy 1974, p. 37-38

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 91.

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Tóth 1983, p. 21

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974, p. 43

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Tóth 1983, p. 21; Mócsy 1974, p. 43-44

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Tóth 1983, p. 21; Mócsy 1974, p. 43-44

- ↑ Barkóczi 1980, p. 89; Mócsy 1974, p. 44

- ↑ Wilkes 1992, p. 207-208.

- 1 2 Barkóczi 1980, p. 92.

- ↑ Pannonia — United Nations of Roma Victrix

- ↑ Marquez-Grant, Nicholas; Fibiger, Linda (21 March 2011). The Routledge Handbook of Archaeological Human Remains and Legislation, Taylor & Francis, page 381. ISBN 9781136879562.

- 1 2 3 4 Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 14.

- ↑ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 15.

- ↑ Petruska 1983, p. 301.

- 1 2 Petruska 1983, p. 302.

- ↑ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 18.

- ↑ Harvey, Bonnie C. (2003). Attila, the Hun – Google Knihy. ISBN 0-7910-7221-5. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- ↑ Elekes, Lederer & Székely 1961, p. 13.

Sources

- Benda, Kálmán; Solymosi, László, eds. (1983). Magyarország történeti kronológiája [Historical chronology of Hungary] (PDF). Vol. 1. A kezdetektől 1526-ig. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963 05 3182 8.

- Kovács, Tibor. "őskőkor-vaskor". In Benda & Solymosi (1983).

- Tóth, István. "római kor". In Benda & Solymosi (1983).

- Lengyel, Alfonz; Radan, George T., eds. (1980). The archaeology of Roman Pannonia (PDF). Lexington, Budapest: University Press of Kentucky, Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 0-8131-1370-9.

- Trogmayer, Ottó. "Pannonia before the Roman conquest". In Lengyel & Radan (1980).

- Barkóczi, László. "History of Pannonia". In Lengyel & Radan (1980).

- Wilkes, John (1992). The Illyrians (1st ed.). Bodmin: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-14671-7.

- Mócsy, András (1974). Pannónia a korai császárság idején [Pannonia during the Early Empire] (PDF). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963 05 0293 3.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Given, John (2014). The Fragmentary History of Priscus. Merchantville, New Jersey: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 9781935228141.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2006). "The Huns and South Pannonia". Byzantinoslavica. 64: 29–76.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2015). "Late Antique Dalmatia and Pannonia in Cassiodorus' Variae". Povijesni prilozi. 49: 9–80.

- Gračanin, Hrvoje (2016). "Late Antique Dalmatia and Pannonia in Cassiodorus' Variae (Addenda)". Povijesni prilozi. 50: 191–198.

- Janković, Đorđe (2004). "The Slavs in the 6th Century North Illyricum". Гласник Српског археолошког друштва. 20: 39–61.

- Mirković, Miroslava B. (2017). Sirmium: Its History from the First Century AD to 582 AD. Novi Sad: Center for Historical Research.

- Mócsy, András (2014) [1974]. Pannonia and Upper Moesia: A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781317754251.

- Popović, Radomir V. (1996). Le Christianisme sur le sol de l'Illyricum oriental jusqu'à l'arrivée des Slaves. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9789607387103.

- Várady, László (1969). Das Letzte Jahrhundert Pannoniens (376–476). Amsterdam: Verlag Adolf M. Hakkert.

- Whitby, Michael (1988). The Emperor Maurice and his Historian: Theophylact Simocatta on Persian and Balkan warfare. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822945-2.

- Wozniak, Frank E. (1981). "East Rome, Ravenna and Western Illyricum: 454-536 A.D." Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 30 (3): 351–382.

- Zeiller, Jacques (1918). Les origines chrétiennes dans les provinces danubiennes de l'Empire romain. Paris: E. De Boccard.

- Elekes, Lajos; Lederer, Emma; Székely, György (1961). Magyarország története [History of Hungary] (PDF). Vol. I. Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó.

- Petruska, Magdolna (1983). "A Danuvius partján" [On the shore of the Danuvius]. In Gyulás, Istvánné (ed.). Az antik Róma napjai [The days of ancient Rome]. Tankönyvkiadó.

- Alföldi, András (2004). Patay-Horváth, András; Forisek, Péter (eds.). Magyarország népei és a Római Birodalom — Keletmagyarország a római korban. Attraktor. ISBN 963-9580-05-8.

- Boren, Henry C. (1977). Rabb, Theodore K. (ed.). Roman Society: A Social, Economic, and Cultural History. Toronto: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. ISBN 0-669-84681-3.

- Marczali, Henrik (1911). Magyarország története. Vol. 1. Budapest: Athenaum Irodalmi és Nyomadi Részvénytársulat.

Further reading

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 680.

- "Pannonia". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). 29 March 2018.

- Pannonia map

- Pannonia map

- Aerial photography: Gorsium - Tác - Hungary

- Aerial photography: Aquincum - Budapest - Hungary

44°54′00″N 19°01′12″E / 44.9000°N 19.0200°E

|

| Notes:

|