The Kuntillet Ajrud inscriptions describe art featuring Yahweh found on and near an amphora. They date to the end of the 8th century BC[2] in the Sinai Peninsula.[3]

The inscriptions were discovered during excavations in 1975–1976, during the Israeli occupation of the Sinai peninsula, but were not published in full until 2012[4][5] or arguably later.

The inscriptions have been called "the pithoi that launched a thousand articles"[6] due to their influence on the fields of Ancient Near East and Biblical studies, raising and answering many questions about the relationship of Yahweh and Asherah.

Description

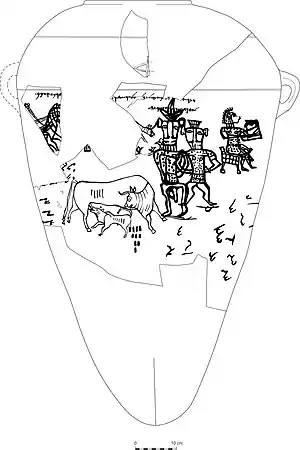

The most famous inscriptions are found on two pithoi.[7] Pithos A's obverse is pictured. The central figures are anthropomorphic yet bovid and have writing above their heads.

The reverse has a line of ambiguous mammals including most clearly a boar. The remaining below, drawn more confidently, are all goddess symbols: a pair of caprids flanking a sacred tree, on bottom a lion. The central figure:

"It is mainly a tree trunk with branches and shoots coming out from it, eight in flower and eight in bud. Pirhiya Beck notes that the tree may be compared with Phoenician examples which show lotus and bud. Its overall form, however, is curious. The flowers are not quite lotuses. The trunk seems like that of a palm tree, but at the top of the trunk is a feature that looks rather like a large almond nut, with the pits of its shell clearly shown. Interestingly, three main branches come from each side of the trunk, and the other two flowering shoots and two minor budding shoots (or shoots with small almond nuts) come from the ’almond’ motif. Like the menorah, then, this representation of an asherah has three branches coming from each side of a central trunk. As we have seen, in the drawings of the Lachish ewer, the trees shown also have three branches coming from a central trunk and look very like menorot. In the Ta’anach stands, the tree is an upright trunk with several furled fronds coming out from the two sides; in one case six and in the other eight.[8]

Pithos B has worshipers and other elements.

Epigraphs

Scholars disagree about the particulars of the translation.

Pithos A

This says [PN1]... Say to Yehal and to Yoasah and to [PN2... I have b]lessed before Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah.

Pithos B

... before Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah [...] whatever he shall ask of anyone, may he grant it [...] and may Yahweh give him according to his heart.

Plaster Fragment

When El dawned in ... [ ] bzrh H br[

the mountains melted [ ] wymsn hrm[

the peaks grew weak [ ] wyrkn pbnm[

Bless Baal on the day of wa[r ] lbrk bcl bym mlh[mh

The Name of El on the day of wa[r ] lšm H bym mlh[mh[9]

Note, the phrase "the mountains melted" is also used in the Torah.

Plaster Fragment

...]יתה .הוהי בטיה.[ ]2 התרשאלו .נמית [.] הוה[ ]ל .ונתי [...] ועבשיו .ממיכרא .[י] 1 [May] he lengthen their days, and may they be satisfied [...] may they be given by [Ya]hweh-of-Teman by [his] Ašerah [and] Yahweh-of-the-Te[man] favored...[10]

Grammar

The final h on the construction yhwh šmrn w'šrth is "his" in "Yahweh and his Asherah."[7][11] This is well-attested earlier[12] but unusual in use with personal or divine names; Z Zevit suggests *’ašerātā as a "double feminization."[13] The localized Yahweh, "of" Samaria and Teman, (a byword for Edom,) is unseen in the Tanakh.[14] Context of Scripture II (p 172) points out the oddity of interpreting a preposition -l with the preceding word rather than the following; it's not clear whether this peculiarity unique to COS's reading as others refer to a prefix l- "to" or in similar cases l- vocative.[15]

Interpretation

The references to Samaria (capital of the kingdom of Israel) and Teman (that is, the local incarnation of Yahweh) suggest that Yahweh had a temple in Samaria, while raising questions about the relationship between Yahweh and Kaus, the national god of Edom.[16] Such questions had previously been raised due to the Tanakh's apparent reluctance to name the deity.

It has been suggested that the Israelites may have considered Asherah as the consort of Baʿal, due to the anti-Asherah ideology that was influenced by the Deuteronomistic Historians, at the later period of the kingdom.[17]

Near pithos A's blessings from "Yahweh and his Asherah", there appears a cow feeding its calf.[18] Examples of this motif in its ambiguity can be seen in Frau & Goettin, 1983.

Context in situ

The site didn't appear to be a village, which raised the question: what was it? Some guessed it was a temple. Some said the lack of evidence of cultic activity meant it had been a mere caravanserei, or equivalent to an Iron Age truck stop. Lissovsky pointed out that sacred trees (typically[19]) leave nothing to archaeology.[20] Meshel imagines the nearby tree grove increased the sanctity of the area, a bamah (“high place”) may have been in Building B, and four maṣṣebot-like cultic stones that were found in Building A might reveal a cultic nature of the site.[21]

The pithoi were found among over 1000 Judean pillar figurines, in spaces with graphic walls:

"Pirhiya Beck, in her lengthy analysis of Horvat Teman’s finds, described this wall painting on plaster in some detail. The surviving fragments preserve the profile of a human head facing right with an eye and ear(?) all drawn in red outline, the eyeball and hair rendered in black, and a red object with black markings which Beck identified as a lotus blossom, concealing the mouth of the human figure. Additional plaster fragments show the figure dressed in a yellow garment with a red neckline border and a double collar-band drawn in red and encasing rows of black dots. Also discernable is a chair with a garment depicted in elaborate arrays of color (yellow, black, and red), part of the chair’s frame, pomegranates, and an unidentifiable plant. Beck pointed out that the size of the scene is impressive measuring some 32 cm in height, by far the largest mural at the site. She also speculated that these fragments are remnants of a larger scene that may have included several human figures participating in some type of ceremony with various plants in the background.12... Two installations located along the northern wall of building A’s courtyard can be interpreted as additional evidence for the observance of sacred ritual within the court yard..."[7]

Phallus misstep

Previous illustrations of the figures added a penis and testes to the smaller standing bovid. When publicity called this matching pair to note, the public asked if this were a depiction of a gay God. Reporter Nir Hasson interviewed the archaeologist and author[7] editionis principis:

"One day archaeologist Uzi Avner called me and told me that he was looking at the exhibits at the Israel Museum and that he thinks the smaller figure has nothing between its legs. We rushed to the museum and they opened the display case for us. We had the Israel Museum restorer with us, who promised me that he had gentle hands, and with a light brush he cleaned it and it turned out that there was nothing [there]. Since then we have been careful to draw the picture with one figure with and one without. This made it easier for those claiming that they were male and female."

— Ze'ev Meshel, archaeologist[22]

See also

- Khirbet el-Qom - similar and roughly contemporaneous[23] epigraphy

- Arad ostraca

- Revadim Asherah

- Deir Alla Inscription - the Balaam inscription

References

- ↑ Joan, Eahr (2018-05-09). "170. 800-700, Kuntillet Ajrud and Khirbet El-Qom.pdf". Joan, Eahr Amelia. Re-Genesis Encyclopedia: Synthesis of the Spiritual Dark– Motherline, Integral Research, Labyrinth Learning, and Eco–Thealogy. Part I. Revised Edition II, 2018. CIIS Library Database. (RGS.). Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- ↑ Singer-Avitz, Lily (2012-10-07). "2009. The Date of Kuntillet 'Ajrud: A Rejoinder". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- ↑ Meshel et al. 2012, pp. 87, 95.

- ↑ Meshel et al. 2012.

- ↑ Puech, 2014, "Trois campagnes de fouilles dirigées par Z. Meshel en 1975 et 1976 mirent au jour des restes de deux bâtiments, le bâtiment A le mieux conservé d'où provient l'essentiel de la documentation (voir figure 1 avec la situation des diverses inscriptions), et le bâtiment B très érodé à l'est. Ont été retrouvés des restes d'une occupation du début du Fer II B qui se sont révélés importants en particulier par l'abondance d'inscriptions gravées ou peintes sur des vases ou sur du plâtre, accompagnées de dessins. Le site à la frontière du royaume de Juda et du désert du Sinai se trouve sur une route de passage dès les temps anciens. La publication récente du rapport final présente les différents apports de ces découvertes, et parmi ces dernières, les inscriptions sont d'un intérêt majeur à plus d'un titre, et méritent quelques lignes complémentaires."

- ↑ "How a Warrior-Storm God became the God of the Israelites and World Monotheism". YouTube. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- 1 2 3 4 Krause 2017, pp. 485–490.

- 1 2 Taylor 1995, pp. 29–54.

- ↑ Lewis, Theodore J. (2013). "Divine Fire in Deuteronomy 33:2". Journal of Biblical Literature. The Society of Biblical Literature. 132 (4): 791–803. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 42912467. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ↑ Splintered Divine. A Kuntillet Ajrud awakening p 264

- ↑ The mispointing ... lack of knowledge of how -h in early (tenth century b.c.e.) orthography can represent a 3 masc sing suffix, known epigraphically. Frank Moore Cross and David Noel Freedman, Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry (SBLDS 21; Missoula, MT: Scholars Press, 1975)

- ↑ -h in 10c BCE orthog. can represend a third masculine singular suffix, well attested from epigraphic... Jnl Bibl Lit 2013 pg 794 referencing Frank Moore Cross, Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry SBLDS 21 Missoula MT Scholars Press 1975)

- ↑ Zevit 1984, pp. 39–47.

- ↑ Splintered divine p 206

- ↑ (Dahood, Ps vol II) Dahood and Penar "Lamedh Vocativi exempla biblio-hebraica", Verbum Domini

- ↑ Keel, Othmar; Uehlinger, Christoph (1998). Gods, Goddesses, And Images of God. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 228. ISBN 9780567085917. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑ Sung Jin Park, "The Cultic Identity of Asherah in Deuteronomistic Ideology of Israel," Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 123/4 (2011): 553–564.

- ↑ Dever, William G. (2005), Did God Have A Wife?: Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, p. 163, ISBN 9780802828521

- ↑ Rich, Viktoria Greenboim (2022-05-16). "7,500-year-old Burial in Eilat Contains Earliest Asherah". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ↑ Na& & Lissovsky 2008, p. 186.

- ↑ Splintered divine. p 266 on Meshel, "The Nature of the Site"

- ↑ "Did God have a wife? A surprising development". Haaretz. 4 April 2018 – via Facebook. Nir Hasson, who wrote the piece titled "A Strange Drawing Found in Sinai Could Undermine Our Entire Idea of Judaism," was contacted by a reader who noticed a discrepancy. Hasson explains.

- ↑ Margalit, Baruch (1989). "Some Observations on the Inscription and Drawing from Khirbet el-Qôm". Vetus Testamentum. Brill. 39 (3): 371–378. ISSN 0042-4935. JSTOR 1519611. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

Bibliography

- Krause, Joachim J. (2017). "Kuntillet ʿAjrud Inscription 4.3: A Note on the Alleged Exodus Tradition". Vetus Testamentum. Brill. 67 (3): 485–490. ISSN 0042-4935. JSTOR 26566694. Retrieved 2023-11-04.

- Meshel, Z.; Ben-Ami, D.; Aḥituv, S.; Freud, L.; Sandhaus, D.; Kuper-Blau, T. (2012). "Chapter 5: The Inscriptions". Kuntillet ʻAjrud (Ḥorvat Teman): An Iron Age II Religious Site on the Judah-Sinai Border. Hazor. Israel Exploration Society. ISBN 978-965-221-088-3.

- Puech, Émile (2014). "Les inscriptions hébraïques de Kuntillet 'Ajrud (Sinaï)". Revue Biblique. 121 (2): 161–194. doi:10.2143/RBI.121.2.3157150. ISSN 2466-8583. JSTOR 44092490.

- Taylor, Joan E. (1995). "The Asherah, the Menorah and the Sacred Tree". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. SAGE Publications. 20 (66): 29–54. doi:10.1177/030908929502006602. ISSN 0309-0892.

- Zevit, Ziony (1984). "The Khirbet el-Qôm Inscription Mentioning a Goddess". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. American Schools of Oriental Research (255): 39–47. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1357074. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- Na&, Nadav; Lissovsky, Nurit (2008-01-01). "Kuntillet 'Ajrud, Sacred Trees and the Asherah". Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 2023-11-10.