Bibliography

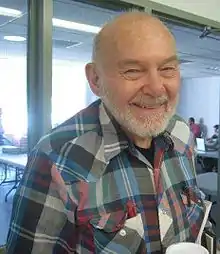

John "Tito" Gerassi was a professor, journalist, author, scholar, political activist and revolutionary born in Paris on July 12, 1931 to Fernando Gerassi, a Turkish-born artist of Sephardic Jewish heritage, and Ukrainian born Stephania Awdykowicz, daughter of Klymentyna Avdykovych, a famous Lviv candy factory owner.[1] Tito died in New York City on July 26, 2012, still inspiring new generations of students as senior professor of Political Science at Queens College of the City University of New York, where he had been teaching since 1978.

Early Years

Moving between Barcelona and Paris, Tito's parents belonged to the cosmopolitan circle of artists and intellectuals who congregated in cafes to argue art and politics, and counted Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir as close friends. When civil war broke out in Spain in 1936, Fernando Gerassi joined the Loyalist forces, serving as a general in the Spanish Army against Franco and later as the inspiration for the figure of Gomez, the artist and revolutionary in Sartre's trilogy "Roads to Freedom". Following the Fascist victory in Spain, the Gerassi family emigrated to the United States in 1940. Gerassi was raised in New York City and attended Columbia University. He spent a decade in journalism, worked as an editor for Time and, later, Newsweek before serving as a foreign correspondent for the New York Times. He left journalism at one point to pursue a career in academia and earned his doctorate at the London School of Economics. (10)

Leading the Vanguard

Tito was one of the most important and influential thinkers and participants in the U.S. and International Left movements throughout his lifetime. As a New York Times correspondent he became a supporter of the Cuban revolution, a friend of Che Guevara and a voice for revolutionary movements throughout Latin American and the world. As a professor of political science at San Francisco State in 1968, he participated in (and was arrested during) the student strikes, which were led by the Black Student Union. Initiated in response to suspension of a radical Black Panther graduate student instructor, these strikes escalated into violent protests resulting in police confrontations and occupation and a complete four month long shut down of the university. During that period,(12) Tito was also a co-founder and contributor to Ramparts Magazine.

One of his students from Queen's College shared these stories about Tito's activism in the 1960's in the Knight News, the Queens College's student-run newspaper. This anonymous student chose to spell ‘America’ with a ‘k’ to verbalize his opinion that the U.S.A has a white supremacist nature.

"His revolutionary convictions, worldviews and beliefs were steeled by what he had seen in his life. As a youth he witnessed one of the most horrible crimes, the lynching of a black youth. When telling us this story in class, he would burst in tears. During his service in the Korean War, he saw how a sergeant made US soldiers indiscriminately shoot innocent women and children crossing a bridge. He worked as a New York Times correspondent and participated in the Cuban revolution along with Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. He had seen firsthand how the imperialist ‘amerikan’ empire dropped bombs on Vietnam. He met Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap who were both head of the revolutionary forces which defeated ‘amerika.’ In ‘amerika,’ he was active in fighting against the police riot in the ’68 Democratic National Convention at a time when all people of color in this country and worldwide were fighting for their liberation. He earned his battle scar when a cop hit him with a baton in his lower spine. From then on, Tito lost his sense of touch on his soles and hands."

Returning to His Roots at Home and Abroad

With Tito's termination from San Francisco State, he was black-listed from other college teaching positions in the U.S. He subsequently moved to Paris in the early 70s, where he had an established a relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre and began conducting a series of interviews with Sartre. His intention was to help the world better understand Sartre's contribution to cultural and political thought beyond the realm of elite intellectuals and academics. He continued to teach American Foreign Policy at the University of Vincennes, where following the 1968 political uprising in Paris, its campus had been abandoned to various left wing factions debating the failure of the 68 revolution and American expatriates hoping to better understand U.S. imperialism and ways to oppose it. (11).

The early 1970s were also significant for Tito's continued developing relationship with black nationalist leadership in the U.S. During this period, he maintained a dialogue with the various competing ideological factions that had developed within the Black Panther Party leadership. A portion of his extensive written correspondence and letters with George Jackson were published posthumously in "Blood in My Eye", four months after George Jackson was murdered during an alleged attempted escape from San Quentin prison. In Blood in my Eye, George acknowledged the depth and relevance of Tito's historical, ideological and lived experience in advancing the liberation of peoples throughout the world from imperialistic exploitation and oppression and cites excerpts from "Overview: The Future Is Revolution" from The Coming of the New International: A Revolutionary Anthology.(8)(9).

- John Gerassi. The Great Fear: The Reconquest of Latin America by Latin Americans. New York: Macmillan, 1963. According to WorldCat, the book is in 883 libraries[2]

- John Gerassi. The Boys of Boise; Furor, Vice, and Folly in an American City. New York: Macmillan, 1966.[3][4][5]

- John Gerassi. North Vietnam: a Documentary. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1968.

- John Gerassi, Venceremos! The Speeches and Writings of Ernesto Che Guevarra, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1968.

- John Gerassi. The Coming of the New International: A Revolutionary Anthology. New York: The World Publishing Company, 1971{8)

- John Gerassi. Towards Revolution. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971

- John Gerassi. The Premature Antifascists: North American Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-39 : an Oral History. New York: Praeger, 1986.[6]

- John Gerassi, Jean-Paul Sartre: Hated Conscience of His Century, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989. According to WorldCat, the book is in 807 libraries[7]

- John Gerassi. The Anachronists. Cambridge: Black Apollo Press, 2006.

- John Gerassi. Talking with Sartre: Conversations and Debates. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009[8]

- John Gerassi and Tony Monchinski, Unrepentant Radical Educator: The Writings of John Gerassi, Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2009.

TBC: List of Collections: audio recordings, letters and correspondence, news reportage and documentary footage - video/film/photography

References

- ↑ "Fernando Gerassi - His Art and Life". fernandogerassi.com. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ↑ WorldCat book entry

- ↑ Review by Beth Kraig The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, v95 n1 (20031201): 39

- ↑ Review by Joseph Bensman Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, v373 (19670901): 284-285

- ↑ Review, by R N Baird Crime & Delinquency, v13 n3 (19670701): 473-474

- ↑ Review by Douglas LittleThe Journal of American History, v74 n1 (19870601): 217-218

- ↑ WorldCat book entry

- ↑ Review by Robert C Robinson Political Studies Review, v10 n2 (20120504): 242

9. George L. Jackson, Blood in My Eye, Random House, Inc., New York 1972

10. NYU Special Collections, John Gerassi Oral History Collection, Historical Biographical Note

11. Personal Journals and Correspondence, Janice E. Cohen 1970-74 Paris, France; New York, New York; Nice, France

12. https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/187296 Diva Bay area Video Archive, John Gerassi interview