| Part of a series on |

| English grammar |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

English auxiliary verbs are a small set of English verbs, which include the English modal auxiliary verbs and a few others.[1]: 19 [2] Although definitions vary, as generally conceived, an auxiliary lacks inherent semantic meaning but instead modifies the meaning of another verb it accompanies. In English, verb forms are often classed as auxiliary on the basis of certain grammatical properties, particularly as regards their syntax. They also participate in subject–auxiliary inversion and negation by the simple addition of not after them.

History of the concept

When describing English, the adjective auxiliary was "formerly applied to any formative or subordinate elements of language, e.g. prefixes, prepositions."[3] As applied to verbs, its conception was originally rather vague and varied significantly.

Some historical examples

The first English grammar, Bref Grammar for English by William Bullokar, published in 1586, does not use the term "auxiliary" but says:

All other verbs are called verbs-neuters-un-perfect because they require the infinitive mood of another verb to express their signification of meaning perfectly: and be these, may, can, might or mought, could, would, should, must, ought, and sometimes, will, that being a mere sign of the future tense. (orthography standardized and modernized)[4]: 353

In volume 5 (1762) of Tristram Shandy, the narrator's father explains that "The verbs auxiliary we are concerned in here,..., are, am; was; have; had; do; did; make; made; suffer; shall; should; will; would; can; could; owe; ought; used; or is wont."[5]: 146–147

Charles Wiseman's Complete English Grammar of 1764 notes that most verbs

cannot be conjugated through all their Moods and Tenses, without one of the following principal Verbs have and be. The first serves to conjugate the rest, by supplying the compound tenses of all Verbs both Regular and Irregular, whether Active, Passive, Neuter, or Impersonal, as may be seen in its own variation, &c.[lower-alpha 1]

It goes on to include, along with have and be, do, may, can, shall, will as auxiliary verbs.[6]: 156–167

W. C. Fowler's The English Language of 1857 has the following to say:

Auxiliary Verbs, or Helping Verbs, perform the same office in the conjugation of principal verbs which inflection does in the classical languages, though even in those languages the substantive verb is sometimes used as a helping verb... I. The verbs that are always auxiliary to others are, May, can, shall, must; II. Those that are sometimes auxiliary and sometimes principal verbs are, Will, have, do, be, and let.[7]: 202

The verbs that all the sources cited above agree are auxiliary verbs are the modal auxiliary verbs may, can, and shall; most also include be, do, and have.

Auxiliary verbs as heads

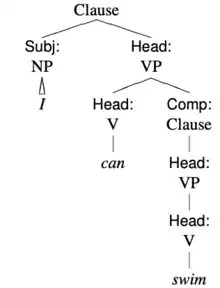

Modern grammars do not differ substantially over membership in the list of auxiliary verbs, though they have refined the concept and, following an idea first put forward by John Ross in 1969,[8] have tended to take the auxiliary verb not as an element subordinate to a "main verb" (a concept that pedagogical grammars perpetuate), but instead as the head of a verb phrase. Examples include The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language and Bas Aarts' Oxford Modern English Grammar.[9]: 104 [10]: 237–239 This is shown in the tree diagram below for the clause I can swim.

The clause has a subject noun phrase I and a head verb phrase (VP), headed by the auxiliary verb can. The VP also has a complement clause, which has a head VP, with the head verb swim.

Auxiliary verbs distinguished grammatically

The list of auxiliary verbs in Modern English, along with their inflected forms, is shown in the following table.

| Citation form |

Modal/ Non-modal |

Plain | Present tense | Past tense | Participles | Confusible lexical homonym?[lower-alpha 3] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral | Contr. | Negative | Neutral | Contr. | Negative | Present | Past | ||||

| will | Modal | will | 'll | won't | would | 'd | wouldn't | none | |||

| may[lower-alpha 4] | may | might | mightn't | none | |||||||

| can | can | can't, cannot | could | couldn't | none | ||||||

| shall | shall | 'll | shan't | should | shouldn't | none | |||||

| must | must | mustn't | none | ||||||||

| ought | ought | oughtn't | exists[lower-alpha 5] | ||||||||

| need[lower-alpha 6] | need | needn't | exists | ||||||||

| dare[lower-alpha 6] | dare | daren't | dared[lower-alpha 7] | exists[lower-alpha 8] | |||||||

| be | Non-modal | be | am, is, are | 'm, 's, 're | ain't,[lower-alpha 9] isn't, aren't | was, were | wasn't, weren't | being | been | exists[lower-alpha 10] | |

| do | do[lower-alpha 11] | does, do | 's[lower-alpha 12] | doesn't, don't | did | 'd[lower-alpha 13] | didn't | exists | |||

| have | have | has, have | 's, 've | hasn't, haven't | had | 'd | hadn't | having | exists | ||

| use[lower-alpha 14] | used | usedn't | exists | ||||||||

| to | to | none | |||||||||

A major difference between this syntactic definition of "auxiliary verb" and the traditional definition given in the section above is that the syntactic definition includes forms of the verb be even when used simply as a copular verb (in sentences like I am hungry and It was a cat), idioms using would (would rather, would sooner, would as soon) that take a finite clause complement (I'd rather you went), and forms of have with no other verb (as in %Have you any change?): uses where it cannot be said to "help" any other verb.[9]: 103, 108, 112

The NICE criteria

One set of criteria for distinguishing between auxiliary and lexical verbs is F. R. Palmer's "NICE": "Basically the criteria are that the auxiliary verbs occur with negation, inversion, 'code', and emphatic affirmation while the [lexical] verbs do not."[1]: 15, 21 [lower-alpha 15]

| Auxiliary verb | Lexical verb | |

|---|---|---|

| Negation | I will not eat apples. I won't eat apples. |

*I eat not apples. *I eatn't apples. |

| Inversion | Has Lee eaten apples? | *Eats Lee apples? |

| Code | Can it devour 3 kg of meat? / Yes it can. |

Does it devour 3 kg of meat? / *Yes it devours. |

| Emphatic affirmation | You say we're not ready? We ARE ready. |

You say we didn't practise enough? *We PRACTISED enough. |

NICE: Negation

Clausal negation most commonly employs an auxiliary verb,[lower-alpha 16] for example, we can't believe it'll rain today or I don't need an umbrella. Up until Middle English, lexical verbs could also participate in clausal negation, so a clause like Lee eats not apples would have been grammatical,[15]: vol 2, p 280 but this is no longer possible in Modern English, where lexical verbs require "do‑support".[lower-alpha 17]

Palmer writes that the "Negation" criterion is "whether [the verb] occurs with the negative particle not, or more strictly, whether it has a negative form",[1]: 21 the latter referring to negatively inflected won't, hasn't, haven't, etc. (Not every auxiliary verb has such a form in today's Standard English.)

NICE: Inversion

Although English is a subject–verb–object language, an interrogative main clause puts a verb before the subject. This is called subject–auxiliary inversion because only auxiliary verbs participate in such constructions. Again, in Middle English, lexical verbs were no different; but in Modern English *Eats Lee apples? is ungrammatical, and do‑support is again required (Does Lee eat apples?).

NICE: Code

Palmer attributes this term to J. R. Firth,[lower-alpha 18] and writes:

There are sentences in English in which a full verb is later 'picked up' by an auxiliary. The position is very similar to that of a noun being 'picked up' by a pronoun. [. . ] If the initial sentence, which contains the main verb, is not heard, all the remainder is unintelligible; it is, in fact, truly in code. The following example is from Firth:

- Do you think he will?

- I don't know. He might.

- I suppose he ought to, but perhaps he feels he can't.

- Well, his brothers have. They perhaps think he needn't.

- Perhaps eventually he may. I think he should, and I very much hope he will.[1]: 25

Attempting to remove the complement(s) of a lexical verb normally has an ungrammatical result (Did you put it in the fridge? / *Yes, I put) or an anomalous one (Did you eat the chicken? / #Yes, I ate). However, if a number of conditions are met, the result may be acceptable.[9]: 1527–1529

NICE: Emphatic affirmation

"[A] characteristic of the auxiliaries is their use in emphatic affirmation with nuclear stress upon the auxiliary", as in You must see him. Palmer concedes that "any verbal form may have nuclear stress"; thus We saw them; however, auxiliaries stressed in this way are used for "the denial of the negative", whereas lexical verbs again use do‑support.[1]: 25–26

- You say you heard them? / No, we SAW them.

- You can't have seen them. / We DID see them.

NICE is widely cited (with "emphatic affirmation" usually simplified as "emphasis"): as examples, by A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language (1985),[11]: 121–124 [lower-alpha 19] The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (2002),[9]: 92–101 and the Oxford Modern English Grammar (2011).[10]: 68–69

The NICER criteria

A revised set of criteria, NICER, owes much to NICE but does more than merely add a fifth criterion to it.

| Auxiliary verb | Lexical verb | |

|---|---|---|

| (Finite) Negation | Lee will not eat apples. | *Lee eats not apples. |

| Inversion | Has Lee eaten apples? | *Eats Lee apples? |

| Contraction of not | didn't, shouldn't, isn't | *eatn't, *gon't, *maken't |

| (Post-auxiliary) Ellipsis | Lee was eating and Kim was too. | *Lee kept eating and Kim kept too. |

| Rebuttal | A: We shouldn't eat apples.

B: We should SO. |

A: We didn't try to eat apples.

B: *We tried SO. |

NICER: Negation

Auxiliary verbs can be negated with not; lexical verbs require do-support: a less stringent version of "negation" as the first criterion of NICE.

NICER: Inversion

The same as "inversion" as the second criterion of NICE.

NICER: Contraction of not

Most English auxiliary verbs have a negative inflected form with -n't,[17] commonly regarded as a contracted form of not. No lexical verb has. A small number of defective auxiliary verbs lack this inflection: mayn't is now dated, and there is no universally accepted negative inflection of am: amn't is dialectal, the acceptability of ain't depends on the variety of Standard English, and aren't is only used when it and I are inverted (Aren't I invited?, compare *I aren't tired).[9]: 1611–1612 For do, must, used (/just/), and (depending on the variety of Standard English) can, the negative inflected form is spelt as expected but its pronunciation is anomalous (change of vowel in don't and perhaps can't; elision of /t/ within the root of mustn't and usedn't); for shan't and won't, both the pronunciation and the spelling are anomalous.[9]: 1611

NICER: Ellipsis

The same as "code" as the third criterion of NICE.

NICER: Rebuttal

When two people are arguing, one may use a stressed too or so to deny a statement made by the other. For example, having been told that he didn't do his homework, a child may reply I did too. This kind of rebuttal is impossible with lexical verbs.

Infinitival to

Various linguists, notably Geoff Pullum, have suggested that the to of I want to go (not the preposition to as in I went to Rome) is a special case of an auxiliary verb with no tensed forms.[18][lower-alpha 20] Rodney Huddleston argues against this position in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language,[9]: 1183–1187 but Robert Levine counters these arguments.[20] In a book on the historical emergence and spread of infinitival to, Bettelou Los calls Pullum's arguments that it is an auxiliary verb "compelling".[21]

In terms of the NICER properties, examples like it's fine not to go show that to allows negation. Inversion, contraction of not, and rebuttal would only apply to tensed forms, and to is argued to have none. Although rebuttal is not possible, it does allow ellipsis: I don't want to.

(Had) better, (woul)d rather, and others

With their normal senses (as in You had better/best arrive early), had/'d better and had/'d best are not about the past. Indeed they do not seem to be usable for the past (*Yesterday I had better return home before the rain started); and they do not occur with other forms of have (*have/has better/best). The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language observes:

If we take [the had in had better] as a distinct lexeme, we will say that it has been reanalysed as a present tense form (like must and ought). . . . [In view of its syntactic behaviour], it undoubtedly should be included among the non-central members of the modal auxiliary class.[9]: 113

Expressions ranging from had better to would rather have been argued to comprise "a family of morphosyntactic configurations with a moderate degree of formal and semantic homogeneity".[22]: 3 They would be:

- Superlative modals: had best, 'd best

- Comparative modals: had better, 'd better, better, would rather, 'd rather, had rather, should rather, would sooner, 'd sooner, had sooner, should sooner

- Equative modals: would (just) as soon as, may (just) as well, might (just) as well

Among these, had better, 'd better, better occur the most commonly. They express either advice or a strong hope: a deontic and an optative sense respectively.[22]: 3–5

Among these three forms, 'd better is the commonest in British English and plain better the commonest in American English.[22]: 11 However, the syntactic category of plain better when used in this or a similar way is not always clear: while it may have been reanalysed as an independent modal auxiliary verb – one with no preterite form and also no ability to invert (*Better I leave now?) – it can be an adverb instead of a verb.[22]: 21–23

Auxiliaries as "helping" verbs

An auxiliary verb is traditionally understood as a verb that "helps" another verb by adding (only) grammatical information to it.[lower-alpha 21] So understood, English auxiliaries include:

- Do when used to form questions (Do you want tea?), to negate (I don't want coffee), or to emphasize (I do want tea) (see do-support)

- Have when used to express perfect aspect (He had given his all)

- Be when used to express progressive aspect (They were singing) or passive voice (It was destroyed)

- The modal auxiliary verbs, used with a variety of meanings, principally relating to modality (He can do it now)

However, this understanding of auxiliaries has trouble with be (He wasn't asleep; Was he asleep?), have (%He hadn't any money; %He hadn't any money), and would (Would you rather we left now?), each of which behaves syntactically like an auxiliary verb even when not accompanying another verb. Other approaches to defining auxiliary verbs are described below.

Contributions to meaning and syntax

Be

Be, followed by the past participle of a lexical verb, realizes the passive voice: He was promoted.[9]: 1427ff Its negative and interrogative versions (He wasn't promoted; Was he promoted?), lacking the need for do‑support, show that this is auxiliary be. (This simple test can be repeated for the other applications of be briefly described below.)

(However, the lexical verb get can also form a passive clause: He got promoted.[9]: 1429–1430 }} This is a long-established construction.[23]: 118 )

Followed by the present participle of a verb (whether lexical or auxiliary), be realizes the progressive aspect: He was promoting the film.[9]: 117, 119ff

Either may be confused with the use of a participial adjective (that is, an adjective derived from and homonymous with a participle): He was excited; It was exciting.[lower-alpha 22]

What The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language terms quasi-modal be normally imparts a deontic meaning: that of He is never to come here again approximates to that of "He must never come here again".[9]: 113–114 In conditional contexts, was to (if both informal and with a singular subject) or were to imparts remoteness: If I were to jump out of the plane, . . . (compare with the open conditional If I jumped out of the plane, . . .).[9]: 151 In common with modal auxiliary verbs, quasi-modal be has no secondary form.[9]: 114

What the same work terms motional be only occurs as a past participle and after the verb have in a perfect construction, and with no verb following it: I've twice been to Minsk. Most of the NICE/NICER criteria are inapplicable, but sentences such as I don't need to go to the Grand People's Study House as I've already been show that it satisfies the "code" and "ellipsis" criteria of NICE and NICER respectively and thus is auxiliary rather than lexical be.[9]: 114

What it terms copular be links a subject, typically a noun phrase, and a predicative complement, typically a noun phrase, adjective phrase, or preposition phrase. Ascriptive copular be ascribes a property to the subject (The car was a wreck); specifying copular be identifies the subject (The woman in the green shoes is my aunt Louise) and can be reversed with a grammatical result (My aunt Louise is the woman in the green shoes). Be in an it‑cleft (It was my aunt Louise who wore the green shoes) is specifying.[9]: 266–267

Auxiliary be also takes as complements a variety of words (able, about, bound, going and supposed among them) that in turn take as complements to‑infinitival subordinate clauses for results that are highly idiomatic (was about/supposed to depart, etc).[24]: 209

Do

The auxiliary verb do is primarily used for do‑support. This in turn is used for negation, interrogative main clauses, and more.

If a positive main clause is headed by an auxiliary verb, either the addition of not or (for most auxiliary verbs) a ‑n't inflection can negate. So They could reach home before dark becomes They couldn't reach home before dark. (This is the "negation" of NICE and NICER.) However, a lexical verb has to be supported by the verb do; so They reached home before dark becomes They didn't reach home before dark.[9]: 94–95

If a declarative main clause is headed by an auxiliary verb, simple inversion of subject and verb will create a closed interrogative clause. So They could reach home before dark becomes Could they reach home before dark?. (This is the "inversion" of NICE and NICER.) However, a lexical verb requires do; so They reached home before dark becomes Did they reach home before dark? For an open interrogative clause, do has the same role: How far did you get?[9]: 95

Although interrogative main clauses are by far the most obvious contexts for inversion using do‑support, there are others: While exclamative clauses usually lack subject–auxiliary inversion (What a foolish girl I was), it is a possibility (What a foolish girl was I[25]); the inverted alternative to How wonderful it tasted! would be How wonderful did it taste! A negative constituent that is not the subject can move to the front and trigger such inversion: None of the bottles did they leave unopened. A phrase with only can do the same: Only once did I win a medal. Ditto for phrases starting with so and such: So hard/Such a beating did Douglas give Tyson that Tyson lost. And in somewhat old-fashioned or formal writing, a miscellany of other constituents can be moved to the front with the same effect: Well do I remember, not so much the whipping, as the being shut up in a dark closet behind the study;[26]for years and years did they believe that France was on the brink of ruin.[27][9]: 95–96

Other than via a negative inflection (don't, doesn't), the verb do does not typically contribute any change in meaning, except when used to add emphasis to an accompanying verb. This is described as an emphatic construction,[11]: 133 as an emphatic version of the declarative clause,[10]: 74 as having emphatic polarity,[9]: 97–98 or is called the emphatic mood: An example would be (i) I DO run five kilometres every morning (with intonational stress placed on do), compared to plain (ii) I run five kilometres every morning. It also differs from (iii) I RUN five kilometres every morning (with the stress on run): A context for (i), with its "emphasis on positive polarity", would be an allegation that the speaker didn't do so every morning; for (iii), with its "emphasis on lexical content", an allegation that the speaker merely walked. Do can be used for emphasis on negative polarity as well: He never DID remember my birthday.[9]: 98

Negative imperative sentences require auxiliary do, even when there is another auxiliary verb. The declarative sentence They were goofing off is grammatical with the single auxiliary be; but the imperative sentence Don't be goofing off when the principal walks in adds don't. (Optionally, you may be added in front of or immediately after don't. A longer subject would normally come after: Don't any of you be goofing off. . . .)[9]: 928 For emphatic positive polarity, do is again added; thus standard Be quiet becomes emphatically positive Do be quiet.[9]: 929

Have

Followed by the past participle of a verb (whether lexical or auxiliary), the auxiliary verb have realizes a perfect tense: Has she visited Qom?; Has she been to Qom?. In addition to its primary forms (have/‑ve, has/‑s, had/‑d, haven't, hasn't, hadn't), it has a plain form (She could have arrived) and a present participle (I regret having lost it), but no past participle.[9]: 111

The present perfect tense is illustrated by I've left it somewhere; the past perfect (also called the preterite perfect) tense by I'd left it somewhere.[9]: 140–141 A full description of their uses is necessarily complex: The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language discusses "four major uses of the present perfect: the continuative, the experiential (or 'existential') perfect, the resultative perfect, and the perfect of recent past",[9]: 143 and its treatment of the perfect is long and intricate.[9]: 139–148 Very simply, the present perfect refers to the past in a way that has some relevance to the present.[28]: 63–64 The perfect is also used in contexts that require both past reference and a secondary verb form (He seems to have left; Having entered, he took off his coat).[28]: 65–66

"Perfect" is a syntactic term; in the context of English, "perfective" is a matter of semantic interpretation. (A number other languages do have fairly direct grammatical expression of perfectivity.) In English, a sentence using a perfect tense may or may not have a perfective interpretation.[28]: 57–58

When used to describe an event, have is exclusively a lexical verb (*Had you your teeth done?; Did you have your teeth done?; *Had you a nap?; Did you have a nap?). When used to describe a state, however, for many speakers (although for few Americans or younger people) it is not necessarily a lexical verb: there is also an auxiliary option: (he'd stop at a pub, settle up with a cheque because he hadn't any money on him;[29] Hasn't he any friends of his own?;[30] I'm afraid I haven't anything pithy to answer;[31] This hasn't anything directly to do with religion[32]).[9]: 111–112 [28]: 54 An alternative to auxiliary verb have in this sense is have got, although this is commoner among British speakers, and less formal[9]: 111–113 (Has he got old news for you;[33] It hasn’t got anything to do with the little green men and the blue orb;[34] What right had he got to get on this train without a ticket?;[35] Hasn't he got a toolbox?[36]).

With their meaning of obligation, have to, has to and had to – distinctive in rarely if ever being rendered as 've to, 's to and 'd to[37] – can use auxiliary have for inversion (if he wants to compel A. to do something to what Court has he to go?;[38] How much further has he to go?;[39] Now why has he to wait three weeks?[40]), although lexical have is commoner.

Use

After noting how constructions employing used (We used to play tennis every week), would (We would play tennis every week), and the preterite alone (We played tennis every week) often seem to be interchangeable, Robert I. Binnick teases them apart, concluding that used to is an "anti-present-perfect": whereas the present perfect "includes the present in what is essentially a period of the past", the used to construction "precisely excludes [it]"; and further that

The whole point of the used to construction is not to report a habit in the past but rather to contrast a past era with the present. . . . It's . . . essentially a present tense. . . . Like the present perfect, it is about a state of affairs, not a series of occurrences.[41]: 41, 43

Modal auxiliary verbs

The modal auxiliary verbs contribute meaning chiefly in the form of modality, although some of them (particularly will and sometimes shall) express future time reference. Their uses are detailed at English modal verbs, and tables summarizing their principal meaning contributions can be found in the articles Modal verb and Auxiliary verb.

For more details on the uses of auxiliaries to express aspect, mood and time reference, see English clause syntax.

Contracted forms

Contractions are a common feature of English, used frequently in ordinary speech. In written English, contractions are used in mostly informal writing and sometimes in formal writing.[42] They usually involve the elision of a vowel – an apostrophe being inserted in its place in written English – possibly accompanied by other changes. Many of these contractions involve auxiliary verbs and their negations, although not all of these have common contractions, and there are also certain other contractions not involving these verbs.

Contractions were first used in speech during the early 17th century and in writing during the mid 17th century when not lost its stress and tone and formed the contraction -n't. Around the same time, contracted auxiliaries were first used. When it was first used, it was limited in writing to only fiction and drama. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the use of contractions in writing spread outside of fiction such as personal letters, journalism, and descriptive texts.[42]

Certain contractions tend to be restricted to less formal speech and very informal writing, such as John'd or Mary'd for "John/Mary would" (compare the personal pronoun forms I'd and you'd, which are much more likely to be encountered in relatively informal writing). This applies in particular to constructions involving consecutive contractions, such as wouldn't've for "would not have".

Contractions in English are generally not mandatory as in some other languages. It is almost always acceptable to use the uncontracted form, although in speech this may seem overly formal. This is often done for emphasis: I am ready! The uncontracted form of an auxiliary or copula must be used in elliptical sentences where its complement is omitted: Who's ready? I am! (not *I'm!).

Some contractions lead to homophony, which sometimes causes errors in writing. Confusion is particularly common between it's (for "it is/has") and the pronoun possessive its, and sometimes similarly between you're and your. For the confusion of have or -'ve with of (as in "would of" for would have), see Weak and strong forms in English.

Contractions of the type described here should not be confused with abbreviations, such as Ltd. for "Limited (company)". Contraction-like abbreviations, such as int'l for international, are considered abbreviations as their contracted forms cannot be pronounced in speech. Abbreviations also include acronyms and initialisms.

Negative form of am

Although there is no contraction for am not in standard English, there are certain colloquial or dialectal forms that may fill this role. These may be used in declarative sentences, whose standard form contains I am not, and in questions, with standard form am I not? In the declarative case the standard contraction I'm not is available, but this does not apply in questions, where speakers may feel the need for a negative contraction to form the analog of isn't it, aren't they, etc. (see § Contractions and inversion below).

The following are sometimes used in place of am not in the cases described above:

- The contraction ain't may stand for am not, among its other uses. For details see the next section, and the separate article on ain't.

- The word amnae for "am not" exists in Scots, and has been borrowed into Scottish English by many speakers.[lower-alpha 23]

- The contraction amn't (formed in the regular manner of the other negative contractions, as described above) is a standard contraction of am not in some varieties, mainly Hiberno-English (Irish English) and Scottish English.[17][44] In Hiberno-English the question form (amn't I?) is used more frequently than the declarative I amn't.[lower-alpha 23] (The standard I'm not is available as an alternative to I amn't in both Scottish English and Hiberno-English.) An example appears in Oliver St. John Gogarty's impious poem The Ballad of Japing Jesus: "If anyone thinks that I amn't divine, / He gets no free drinks when I'm making the wine". These lines are quoted in James Joyce's Ulysses,[45] which also contains other examples: "Amn't I with you? Amn't I your girl?" (spoken by Cissy Caffrey to Leopold Bloom in Chapter 15).[46]

- The contraction aren't, which in standard English represents are not, is a very common means of filling the "amn't gap" in questions: Aren't I lucky to have you around? Some twentieth-century writers described this usage as "illiterate" or awkward; today, however, it is reported to be "almost universal" among speakers of Standard English.[47] Aren't as a contraction for am not developed from one pronunciation of "an't" (which itself developed in part from "amn't"; see the etymology of "ain't" in the following section). In non-rhotic dialects, "aren't" and this pronunciation of "an't" are homophones, and the spelling "aren't I" began to replace "an't I" in the early part of the 20th century,[48] although examples of "aren't I" for "am I not" appear in the first half of the 19th century, as in "St. Martin's Day", from Holland-tide by Gerald Griffin, published in The Ant in 1827: "aren't I listening; and isn't it only the breeze that's blowing the sheets and halliards about?"

There is therefore no completely satisfactory first-person equivalent to aren't you? and isn't it? in standard English. The grammatical am I not? sounds stilted or affected, while aren't I? is grammatically dubious, and ain't I? is considered substandard.[49] Nonetheless, aren't I? is the solution adopted in practice by most speakers.

Other colloquial contractions

Ain't (described in more detail in the article ain't) is a colloquialism and contraction for "am not", "is not", "was not" "are not", "were not" "has not", and "have not".[50] In some dialects "ain't" is also used as a contraction of "do not", "does not", "did not", "cannot/can not", "could not", "will not", "would not" and "should not". The usage of "ain't" is a perennial subject of controversy in English.[51]

"Ain't" has several antecedents in English, corresponding to the various forms of "to be not" and "to have not".

"An't" (sometimes "a'n't") arose from "am not" (via "amn't") and "are not" almost simultaneously. "An't" first appears in print in the work of English Restoration playwrights. In 1695 "an't" was used as a contraction of "am not", and as early as 1696 "an't" was used to mean "are not". "An't" for "is not" may have developed independently from its use for "am not" and "are not". "Isn't" was sometimes written as "in't" or "en't", which could have changed into "an't". "An't" for "is not" may also have filled a gap as an extension of the already-used conjugations for "to be not".

"An't" with a long "a" sound began to be written as "ain't", which first appears in writing in 1749. By the time "ain't" appeared, "an't" was already being used for "am not", "are not", and "is not". "An't" and "ain't" coexisted as written forms well into the nineteenth century.

"Han't" or "ha'n't", an early contraction for "has not" and "have not", developed from the elision of the "s" of "has not" and the "v" of "have not". "Han't" also appeared in the work of English Restoration playwrights. Much like "an't", "han't" was sometimes pronounced with a long "a", yielding "hain't". With H-dropping, the "h" of "han't" or "hain't" gradually disappeared in most dialects, and became "ain't". "Ain't" as a contraction for "has not"/"have not" appeared in print as early as 1819. As with "an't", "hain't" and "ain't" were found together late into the nineteenth century.

Some other colloquial and dialect contractions are described below:

- "Bain't" or "bain't", apparently a contraction of "be not", is found in a number of works employing eye dialect, including J. Sheridan Le Fanu's Uncle Silas.[52] It is also found in a ballad written in Newfoundland dialect.[53]

- "Don't" is a standard English contraction of "do not". However, for some speakers "don't" also functions colloquially as a contraction of "does not": Emma? She don't live here anymore. This is considered incorrect in standard English.

- "Hain't", in addition to being an antecedent of "ain’t", is a contraction of "has not" and "have not" in some dialects of English, such as Appalachian English. It is reminiscent of "hae" ("have") in Lowland Scots. In dialects that retain the distinction between "hain't" and "ain't", "hain't" is used for contractions of "to have not" and "ain't" for contractions of "to be not".[54] In other dialects, "hain't" is used either in place of, or interchangeably with "ain't". "Hain't" is seen for example in Chapter 33 of Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: I hain't come back—I hain't been GONE. ("Hain't" is to be distinguished from "haint", a slang term for ghost (i.e., a "haunt"), famously used in the novel To Kill a Mockingbird.)

Multiple contractions

There are many cases of double contraction in English, for example, "'tisn'" ("it is not") and "shouldn't've") ("should not have").

. There are also triple contractions,

. At least one quadruple contraction, "y'all'dn't've" ("you all would not have").

Contractions and inversion

In cases of subject–auxiliary inversion, particularly in the formation of questions, the negative contractions can remain together as a unit and invert with the subject, thus acting as if they were auxiliary verbs in their own right. For example:

- He is going. → Is he going? (regular affirmative question formation)

- He isn't going. → Isn't he going? (negative question formation; isn't inverts with he)

One alternative is not to use the contraction, in which case only the verb inverts with the subject, while the not remains in place after it:

- He is not going. → Is he not going?

Note that the form with isn't he is no longer a simple contraction of the fuller form (which must be is he not, and not *is not he).

Another alternative to contract the auxiliary with the subject, in which case inversion does not occur at all:

- He's not going. → He's not going?

Some more examples:

- Why haven't you washed? / Why have you not washed?

- Can't you sing? / Can you not sing? (the full form cannot is redivided in case of inversion)

- Where wouldn't they look for us? / Where would they not look for us?

The contracted forms of the questions are more usual in informal English. They are commonly found in tag questions. For the possibility of using aren't I (or other dialectal alternatives) in place of the uncontracted am I not, see Contractions representing am not above.

The same phenomenon sometimes occurs in the case of negative inversion:

- Not only doesn't he smoke, ... / Not only does he not smoke, ...

Notes

- ↑ Wiseman uses "regular", "irregular", "active" and "passive" with the meanings they still have in relation to verbs. A "neuter verb", he writes: "Comes from the Latin neuter, neither, because it is neither Active nor Passive, it denotes the existence of a person or thing, making a complete sense of itself, and requires no noun or other word to be joined with it, as, I sleep, we run, she cries, &c." An "impersonal verb", he writes, is one: "Having only the third person singular and plural applied to things both animate and inanimate, as, it freezes, it is said or they say, they grow, &c."[6]: 155

- ↑ Where there is a blank, the auxiliary verb lacks this form. In some cases, a corresponding lexical verb may have the form. For example, lexical verb need has a plain past tense form, but auxiliary verb need does not.

- ↑ More precisely: Does there exist a lexical verb with the same spelling and pronunciation that is synonymous or could be said to have an auxiliary (or copular) function? (Ignored here is any lexical verb – will meaning "exert one's will in an attempt to compel", can meaning "insert into cans", etc – that is unlikely to be mistaken for the auxiliary verb.)

- ↑ "[T]here is evidence that for some speakers [of Standard English] may and might have diverged to the extent that they are no longer inflectional forms of a single lexeme, but belong to distinct lexemes, may and might, each of which – like must – lacks a preterite. . . ."[9]: 109

- ↑ "The use of ought as a lexical verb as in They didn’t ought to go is restricted to non-standard dialects (Quirk et al., 1985[11]: 140) and is claimed by Greenbaum (1996[12]: 155) to be also sometimes found in informal standard usage as well. Lexical ought with the dummy operator do has been condemned in British usage handbooks. . . . What this censure suggests is that lexical ought with periphrastic do is a well-established usage in colloquial [British English]."[13]: 502

- 1 2 An NPI, rare for speakers of Standard American English.[9]: 109

- ↑ Dared has replaced now-archaic durst.[9]: 110n

- ↑ The distinction between auxiliary and lexical is blurred: "lexical dare commonly occurs in non-affirmative contexts without to": She wouldn't dare ask her father; and it also "can be stranded", as in She ought to have asked for a raise, but she didn't dare.[9]: 110

- ↑ Non-standard.

- ↑ Almost exclusively an NPI, found in the contexts exemplified by If you don't be quiet I'll ground you and Why don't you be quiet?[9]: 114

- ↑ Used for the imperative, as in Do be quiet. Uniquely among English auxiliary verbs, untensed do also has a negative inflected form: don't, as in Don't be noisy.[9]: 91–92

- ↑ In questions like What's he do?, rarely written.

- ↑ In questions like What'd he do?, rarely written.

- ↑ Pronounced /jus/ (rhyming with "loose"). Auxiliary verb form used should be distinguished from the homonymous adjective used, as in I've got (very) used to it.[14]: 85 (The homographic verb use /juz/, rhyming with "lose", is lexical only.) "For many speakers [of Standard English], especially younger ones", use /jus/ is exclusively a lexical verb.[9]: 115

- ↑ Rather than "lexical verb", Palmer uses the term "full verb".

- ↑ Clausal negation can be tested by adding a straightforward interrogative tag (one simply asking for confirmation, not expressing incredulity, admiration, etc). A negative clause calls for a positive interrogative tag; thus the positive Do you? within You don't eat beef, do you? shows that You don't eat beef is negative. Despite lacking an auxiliary verb, You never/seldom/rarely eat beef is also negative.

- ↑ At first glance the grammaticality of I hope/guess/suppose/think not may suggest that at least some lexical verbs too have no need for do‑support, but ungrammatical *I hope/guess/suppose/think not you are right shows that this is quite mistaken. Not in these examples does not negate a clause but is instead the negative equivalent of so, a pro-form for a negative proposition.[9]: 1536

- ↑ Palmer does not seem to specify where Firth wrote about this.

- ↑ The authors use NICE but do not name it.

- ↑ Pullum credits unpublished insights of Paul Postal and Richard Hudson, and published work by Robert Fiengo.[19]

- ↑ The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 1989, defines an auxiliary verb as "a verb used to form the tenses, moods, voices, etc. of other verbs".

- ↑ Very simply, if the word ending -ing can take an object; it is a verb; if it can be modified by either too in the sense of "excessively" or very, it is an adjective. (NB if it cannot take an object, it is not necessarily an adjective; if it cannot be so modified by too or very, it is not necessarily a verb. There are also participial prepositions and other complications.)[9]: 540–541

- 1 2 It is used in declarative sentences rather than questions.[43]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Palmer, F. R. (1965). A Linguistic Study of the English Verb. London: Longmans, Green. OCLC 1666825.

- ↑ Warner, Anthony R. (1993). English Auxiliaries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary entry for auxiliary A1c.

- ↑ Bullokar, William (1906). "Bref Grammar for English". In Plessow, Max (ed.). Geschichte der Fabeldichtung in England bis zu John Gay (1726). Nebst Neudruck von Bullokars "Fables of Aesop" 1585, "Booke at large" 1580, "Bref Grammar for English" 1586, und "Pamphlet for Grammar" 1586. Berlin: Mayer & Müller. pp. 339–385 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Sterne, Laurence. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Vol. 5. London – via Laurence Sterne in Cyberspace (Gifu University).

- 1 2 Wiseman, Charles (1764). A Complete English Grammar on a New Plan: For the Use of Foreigners, and Such Natives as Would Acquire a Scientifical Knowledge of Their Own Tongue ... London: W. Nicol – via Google Books.

- ↑ Fowler, William Chauncey (1857). The English Language, in Its Elements and Forms: With a History of Its Origin and Development. London: William Kent & Co. – via Google Books.

- ↑ Ross, John Robert (1969). "Auxiliaries as main verbs" (PDF). Studies in Philosophical Linguistics. 1. Evanston, Illinois: Great Expectations. ISSN 0586-8882 – via Haj Ross's Papers on Syntax, Poetics, and Selected Short Subjects.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2002). The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43146-0.

- 1 2 3 Aarts, Bas (2011). Oxford Modern English Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953319-0.

- 1 2 3 Quirk, Randolph; Greenbaum, Sidney; Leech, Geoffrey; Svartvik, Jan (1985). A Comprehensive Grammar of the English language. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-51734-6.

- ↑ Greenbaum, Sidney (1996). The Oxford English Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861250-6.

- ↑ Lee, Jackie F. K.; Collins, Peter (2004). "On the usage of have, dare, need, ought and used to in Australian English and Hong Kong English". World Englishes. 23 (4): 501–513. doi:10.1111/j.0083-2919.2004.00374.x.

- ↑ Zandvoort, R. W. (1975). A Handbook of English Grammar (7th ed.). London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-55339-3.

- ↑ Hogg, Richard M.; Blake, N. F.; Lass, Roger; Romaine, Suzanne; Burchfield, R. W.; Algeo, John (1992–2001). The Cambridge History of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26474-X. OCLC 23356833.

- ↑ Sag, Ivan A.; Chaves, Rui P.; Abeillé, Anne; Estigarribia, Bruno; Flickinger, Dan; Kay, Paul; Michaelis, Laura A.; Müller, Stefan; Pullum, Geoffrey K.; Van Eynde, Frank; Wasow, Thomas (2020-02-01). "Lessons from the English auxiliary system". Journal of Linguistics. 56 (1): 87–155. doi:10.1017/S002222671800052X. hdl:20.500.11820/2a4f1c47-b2e1-4908-9d82-b02aa240befd. ISSN 0022-2267. S2CID 150096608.

- 1 2 Zwicky, Arnold M.; Pullum, Geoffrey K. (September 1983). "Cliticization vs. inflection: English n't". Language. 59 (3): 502–513. doi:10.2307/413900. ISSN 0097-8507. JSTOR 413900.

- ↑ Pullum, Geoffrey K. (1982). "Syncategorematicity and English infinitival to". Glossa. 16: 181–215.

- ↑ Fiengo, Robert (1980). Surface Structure: The Interface of Autonomous Components. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-85725-4.

- ↑ Levine, Robert D. (2012). "Auxiliaries: To's company". Journal of Linguistics. 48 (1): 187–203. doi:10.1017/S002222671100034X. ISSN 0022-2267.

- ↑ Los, Bettelou (2005). The Rise of the To-Infinitive. Oxford University Press. p. 208. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199274765.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-927476-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Van der Auwera, Johan; Noël, Dirk; Van linden, An (2013). "Had better, 'd better and better: Diachronic and transatlantic variation". In Marín‐Arrese, Juana I.; Carretero, Marta; Arús, Jorge; Van der Auwera, Johan (eds.). English modality: Core, periphery and evidentiality (PDF). Topics in English Linguistics 81. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 119–154. ISBN 9783110286328. Retrieved 29 November 2023 – via University of Liège.

- ↑ Berk, Lynn M. (1999). English Syntax: From Word to Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512353-1.

- ↑ Depraetere, Ilse; Reed, Susan (2020). "Mood and modality in English". In Aarts, Bas; McMahon, April; Hinrichs, Lars (eds.). The Handbook of English Linguistics (2nd ed.). Newark, New Jersey: Wiley. pp. 207–227. doi:10.1002/9781119540618.ch12. ISBN 9781119540564.

- ↑ Mitchell, Joni (1968). "The Gift of the Magi". Joni Mitchell.

- ↑ Groome, Francis Hindes (1895). Two Suffolk Friends. Edinburgh: William Blackwood. p. 10 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ Southey, Robert (1814). Letters from England: By Don Manuel Alvarez Espriella. Vol. 3 (3rd ed.). London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown – via Project Gutenberg.

- 1 2 3 4 Huddleston, Rodney; Pullum, Geoffrey K.; Reynolds, Brett (2022). A Student's Introduction to English Grammar (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-08574-8.

- ↑ Harper, Nick (9 January 2004). "Interview: Jack Charlton". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ "No 2,024: Flipper the dolphin". The Guardian. 12 April 2002. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ Amis, Martin (31 December 1999). "What we'll be doing tonight". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ Brown, Andrew (23 December 2009). "Author! Author!". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ McCrum, Robert (20 April 2008). "Has he got old news for you". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2023.)

- ↑ Luscombe, Richard (13 October 2021). "William Shatner in tears after historic space flight: 'I'm so filled with emotion'". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2023.)

- ↑ Hoggart, Simon (25 November 2000). "No charm and plenty of offence is the railway response to a state of chaos". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2023.)

- ↑ Coren, Victoria (22 August 2010). "A Swann song for real men". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2023.)

- ↑ Kukucz, Marta (2009). Characteristics of English Modal Verbs (PDF) (PhD thesis). Palacký University Olomouc. p. 18.

- ↑ Lord Dynevor (20 July 1926). "Commons Amendment". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 65. Parliament of the United Kingdom: Lords.

- ↑ "12+ Entrance examination: Solihull: Sample paper: Mathematics". Solihull Preparatory School. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ "How does it feel for me?" (PDF). Healthwatch Leeds. NHS Leeds Clinical Commissioning Group. January 2020. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ Binnick, Robert I. (2006). "Used to and habitual aspect in English". Style. 40: 33–45. doi:10.5325/style.40.1-2.33.

- 1 2 Castillo González, Maria del Pilar. Uncontracted Negatives and Negative Contractions in Contemporary English. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. p.23-28.

- ↑ Bresnan, Joan (2002). "The Lexicon in Optimality Theory". In Paolo Merla; Suzanne Stevenson (eds.). The Lexical Basis of Sentence Processing: Formal, Computational and Experimental Issues. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 39–58. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.56.4001. ISBN 1-58811-156-3.

- ↑ Rissanen, Matti (1999). "Isn't it? or is it not? On the order of postverbal subject and negative particle in the history of English". In Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade; Gunnel Tottie; Wim van der Wurff (eds.). Negation in the History of English. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 189–206. ISBN 3-11-016198-2.

- ↑ Joyce, James. "Chapter 1". Ulysses. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22.

- ↑ Joyce, James. "Chapter 15". Ulysses. Archived from the original on 2012-11-29.

- ↑ Jørgensen, Erik (1979). "'Aren't I?' And alternative patterns in modern English". English Studies. 60: 35–41. doi:10.1080/00138387908597940.

- ↑ "aren't I", Merriam-Webster's dictionary of English usage (1995)

- ↑ E. Ward Gilman, ed. (1994). "ain't". Merriam Webster's Dictionary of English Usage (2nd, revised ed.). Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster. pp. 60–62. ISBN 0-87779-132-5.

- ↑ "ain't", Merriam-Webster's dictionary of English usage, 1995.

- ↑ Ryan Dilley, "Why poor grammar ain't so bad" BBC, September 10, 2001, accessed May 13, 2009.

- ↑ J. Sheridan Le Fanu, Uncle Silas, ch. 53 Archived 2012-10-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The Outharbour Planter" by Maurice A. Devine (1859–1915) of Kings Cove, Bonavista Bay, NL: "The times bain't what they used to be, 'bout fifty ye'rs or so ago", as published in Old-Time Songs And Poetry Of Newfoundland: Songs Of The People From The Days Of Our Forefathers (first edition, p. 9, 1927; described here).

- ↑ Malmstrom, Jean (1960). "Ain't Again". The English Journal. 49: 204–205. doi:10.2307/809195. JSTOR 809195.