| Corsairs of Algiers | |

|---|---|

| The Tai'fa of Raïs | |

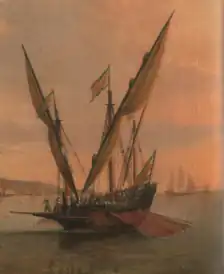

A Corsair of Algiers | |

| Active | 1516-1830 |

| Disbanded | De jure 1830 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Wakil al-Kharadj, or minister of the navy of Algiers and foreign affairs, Kapudan-reïs, “admiral, hierarchical chief of all the reïs” |

| Main location | Algiers |

| Equipment | Yatagan, Nimcha, Kabyle musket, and other locally made weapons |

| Engagements | Algiers expedition (1541) Battle of Lepanto (1571) Odjak of Algiers Revolution French-Algerian War 1681–88 Invasion of Algiers (1775) Battle off Cape Gata (1815) Bombardment of Algiers (1816) Invasion of Algiers in 1830 |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Oruç Reis Hayreddin Barbarossa Occhiali Jan Janszoon Ali Bitchin Mezzo Morto Hüseyin Pasha Raïs Hamidou |

The ta'ifa of reïs (Arabic: طائفة الريس, community of corsair captains) or the Reïs for short, were Barbary pirates based in Ottoman Algeria who were involved in piracy and slave trade in the Mediterranean Sea from the 16th to the 19th century. They were an ethnically mixed group of seafarer,[1] including mostly "Renegades" from European provinces of the Mediterranean and the North Sea, along with a minority of Turks and Moors.[2] Such crews were experienced in naval combat thus making Algiers a formidable pirate base. Its activity was directed against the Spanish empire, but it did not neglect the coasts of Sicily, Sardinia, Naples or Provence. It was the Taifa which, through its captures, maintained the prosperity of Algiers and its finances.[3]

The corsair taifa of Algiers reached the zenith of its power in the first half of the seventeenth century as an Ottoman military elite theoritically. Up until 1626, the Algerian corsair admiral (Kapudan-reis) was invested by the ottoman sultan and was subordinate to the Kapudan Pasha of the Ottoman empire.[4] Often being former Christian slaves and having been promoted in the ta'ifa's chain of command, the admirals and their corsairs were a powerful military and political force in the regency of Algiers, and could even challenge the authority of the Pasha and the Odjak Janissary corps.[5]

Pirates or Privateers ?

The establishment of the Regency of Algiers by the Barbarossa brothers gave the Muslim corso a solid territorial base, which was organized in its beginnings as self-defence as well as a holy war; described as al-jihad fi'l-bahr (holy war at sea) against the Spanish Empire and the Christian Knights who continued the work of the crusades.[6] In the days of Hayreddin Barbarossa and his immediate successors, the reïs were an integral part of the Ottoman navy, but in the 17th century they had become a distinct group.[7] Thus, the corso became a permanent institution in the Regency of Algiers; its main income was included in the state budget. Enriching those who cared for it and returning to the treasury one-fifth of the catch, it was essential to the existence of Algiers, which all the efforts of the government tended to develop. It was also the activity upon which the economical and political prosperity of the Odjak as well as its religious prestige to a great extent depended.[8]

Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius would implicitly admit that Algiers exercised the Jus ad bellum of a sovereign power through its corsairs.[9] This was highlighted in Algiers forcing european powers to recognise a set of ethics and rules that institutionnalized corsairing through a series of treaties concluded between Algiers and these european states, which brought many european authors such as Irish lawyer charles molloy and Dutch legal theorist Cornelius van Bynkershoek to explicitly consider Algiers and other corsairing barbary states entitled to the rights of independent states and were esteemed by definition as enemies (at war) and not pirates (enemies of mankind).[9]

Thus, corsaing acquired both legitimate and religious dimentions which in turn gave it an international dimention that negated the faithless and lawless nature of piracy upon Algerian and other barbary corsairs.[10]

French historian Dianel Panzac, although admitting that the barbary corsairs hardly differed in their methods from pirates that were still distinguishable by their "black flag, an uncertain nationality, the vandalising of the ship, and especially the killing of the crew in order to leave no trace", nevertheless respected the administrative and diplomatic frameworks that North African regencies were bounded with, which is why the barbary warships were classified as privateering vessels and not pirate ships.[11]

Corsair base of Algiers

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

In 1529, Hayreddin Barbarossa seized the Peñon facing the city of Algiers from the Spanish and linked the rock to the port by building the pier.[12] This allowed Algiers to become a secure port for naval and corsair companies in the Mediterranean. The city quickly became the main base for corsairs in the Mediterranean.[13] This domination enabled him to repel several attacks from a certain number of European countries, in particular, in October 1541, that of Charles V, whose troops were defeated by the forces of the regency under the command of Hassan Agha, well aided by the storm which destroyed a good part of the enemy fleet.

In response Hassan Agha ordered the construction of a large artillery piece which was designed in the foundries of Dar Ennahas, near the Bab El Oued gate in 1542, by a Venetian master builder in the pay of the beylerbey of Algiers, Hassan Agha. The cannon was placed during the completion of the "Kheir Eddine pier" at the end, on the Bordj Amar.[14] The Algerians armed in war those of the captured merchant ships which seemed fit for the corso, and also bought ships in Europe. They also had construction sites, located in Bab-el-Oued for large buildings, in Bab-Azoun for those of smaller dimensions. Christian slaves were employed on these shipyards, and the management of which was often entrusted to renegades, even to free Christians as captains of armament or engineers of naval constructions, who hired their services for a time, without being for that put in the obligation to change religion. The masts, yards, sails, ropes, powder, ammunition, artillery pieces, were supplied by the government of the Ottoman Porte and by certain minor powers of Europe, the latter in the form of tribute.[15]

Renegade corsairs of Algiers

The community of corsair captains had become penetrated by adventurers from many parts of the Mediterranean area. Non-Turks who came to Algiers as captives of the Algerian corsairs gained admittance to the ta'ifa of reïs through conversion to Islam and by virtue of their knowledge of the areas the corsairs raided. Unlike in Ottoman Tunisia, where privateers were allowed to equip their own piratical ships, piracy in Ottoman Algeria was a monopoly of the state. The captan-reïs, “admiral, hierarchical chief of all the reïs”, or captain of vessels, was often, after the Pasha, the most important person in the diwan of Algiers.[16]

The rank of Reïs or commander of a corso vessel, was obtained only after an examination passed before the council of reïs, chaired by the captain (admiral) position reserved for the oldest of the reïs, who no longer sailed. Another captain, chosen by the council, commanded the fleet. The reis was the absolute master on board, where the most rigorous discipline reigned.[17]

The influx of "Renegades"; Converts of European origin who brought their knowledge of European coasts and navigation, as well as the expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain, who also imported valuable knowledge in the construction of frigates and brigantines, were important factors that brought growth to the fleet and the corso. Based in Cherchell, they knew the Spanish coastline, thus around the 1570s, the corso took on the aspect of a private enterprise, even if public investments were allocated to arsenals and ports under pressure from the community and the privateers.[18]

According to Diego de Haedo, the fleet of Algiers (including the vessels based at Cherchell) consisted, in 1581, of 35 galliotes - including 2 of 24 benches, 1 of 23 benches, 11 of 22 benches, 8 of 20 benches, 10 of 18 benches, 1 of 19 benches, and 2 of 15 benches — and about 25 frigates (small rowing and undecked vessels), from 8 to 13 benches. More than two thirds of the Algiers galiotes are commanded by European renegades (6 Genoese, 2 Venetians, 2 Albanians, 3 Greeks, 2 Spaniards, 1 French, 1 Hungarian, 1 Sicilian, 1 Neapolitan, 1 Corsican and 3 of their sons).[19] All these renegades occupy the key positions, after the founder of the regency of Algiers, Hayreddin Barbaroassa, it is the Sardinian renegade Hasan Agha (1535-1543), the Corsican Hassan Corso (1549-1556), the Calabrian Uluj Ali Pasha (1568-1571) who ended up with the title of admiral of the fleet, then the Venetian Hassan Veneziano (1577-1580 and 1582-1583).[20] They also took part in the armies of occupation of the subjected zones like local governments before the creation of the three beyliks; of the 23 territorial bosses, 13 are renegades or sons of renegades. Haedo would be able to say :[21]

"In them, reside almost all the power, the influence, the government and the wealth of Algiers".

— Diego de Haëdo, Histoire des rois d'Alger

In the early 17th century, Algiers also became, along with other North African ports such as Tunis, one of the bases for Anglo-Turkish piracy. The peace in Europe forced the Norse privateers to shift their field of activity to the Mediterranean and to serve the enemies of Algiers. Yet many of those privateers converted to Islam and were enlisted in the Algerian corsair Navy. As a result of this privateer spill, international piracy activity in the region has intensified to an unprecedented degree.[6] There were as many as 8,000 renegades in the city in 1634.[22][23]

A contemporary letter states:

"The infinity of goods, merchandise jewels and treasure taken by our English pirates daily from Christians and carried to Algire and Tunis to the great enriching of Mores and Turks and impoverishing of Christians"

— Contemporary letter sent from Portugal to England.[24]

The Algerian corsair fleet

_-_An_Algerine_Ship_off_a_Barbary_Port_-_BHC0751_-_Royal_Museums_Greenwich.jpg.webp)

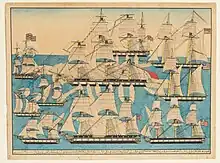

At the beginning of the 17th century, Algiers' pirate fleet numbered 100 ships and employed 8,000 to 10,000 men. The piracy "industry" accounted for 25 percent of the workforce of the city, not counting other activities related directly to the port. The fleet averaged 25 ships in the 1680s, but these were larger vessels than had been used the 1620s, thus the fleet still employed some 7,000 men.[25] The introduction of round ships by the Flemish corsair Zymen Danseker and the arrival of expelled Moriscos from Spain contributed strongly to the development of the fleet of Algiers,[7] which would have been modernized and enlarged,[26] it numbered as follows:

- In 1625, the corsair fleet included six Galleasses, a large number of brigantines and a hundred Galleyes, more than sixty of them were equipped with 24 to 40 guns.[27]

- In 1630, there were about 70 ships in the port of the capital, with what the Algerians owned from the French years prior, and

- in 1632, 13 galleys were found in the port, all of which were driven by oars, and 70 others with sails, and 23 boats of 30 to 50 cannons.

- In 1634, the Algerian fleet consisted of 70 pieces, each of which was armed with between 25 and 40 cannons.

- In 1657, this number decreased to 23 ship, and each ship included 30 to 50 cannons.

- In 1662, there were 22 barges and nine galleys in the capital, and in 1681 there were only 17 barges in the port of Algiers and two large ships with heavy weapons of 112 cannons. These 17 ships were mentioned by their names in the report of sieur hayet, among them: the Golden Mare, the Rose, the little Rose, the city of Algiers, the Marzouk, the Canaria.[28]

- On the consul's Fiolle report, He says that in 1686: "The ship called "the Golden Rose" was armed with 40 cannons, the "Seven Stars" with 30 cannons, the "Golden Lion" equipped with 32 cannons, and that there were also on this date, 10 ships with two bridges, each containing 30 cannons, and ten single-barreled ships, each containing 14 cannons, sometimes reaching 20. There were also two ships with two bridges containing 45 cannons and a fire equipped with 20 cannons, and five other ships, two of them with 50 cannons, two with 30 cannons, and besides that, there were 39 ships for transport and trade".

- It came in the report of Dr. Duke de Grafton dated on October 14, 1687, that the number of Algerian ships in the diversity of their forms and the difference in weight and their cargo amounted to 60 ships, which had 570 cannons in total.[28]

In the 18th century the number of Algerian ships diminished and was varying from 20 to 30 ships and were mostly Xebecs armed with 12 to 32 cannons. During the Barbary Wars the said number increased in 1802 to 66 barges, each with between 25 and 80 long-range cannons, then in 1815 it began to decrease to 41 ships, and there were only five battleships, four barges and 30 ships in 1816, Gouthrot says on that date only two battleships of 50 to 60 cannons, two corvettes with five cannons, two barges of 80 cannons, four galleys of 15 to 26 cannons, and one ship of 20 cannon type "polacre", and 35 ship, the General Consul of the United States of America William Shaler tells about the Algerian Navy in 1815: "The Algerian fleet was composed of five frigates with 38 to 50 cannons and five corvettes", among those ships were the well-known "Al-Marikana", and the Portuguesa also known as "Mashouda", the latter was captured by Rais Hamidou from the Portuguese navy in May 1802 and there were 282 prisoners on its deck, then it was lost and others were burned when Lord admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth attacked Algiers in 1816. There are also names for other ships, such as Miftah al-Salam, Dik al-Marsa, Guide to Alexandria, and others from what the Algerian Navy seized, so it left them with the names known by them before.[29] Two important attacks were the American expedition of 1815, which forced the regency to accept a right of navigation from the Americans, and that of the British and Dutch navies on Algiers in August 1816. The latter suffered great losses and were prevented from landing, but the Algerian armada also loses a very large number of ships including 4 frigates and 8 corvettes, this marked the de facto end of the Algerian Corso.

How the corsairs operated

Jihad against Spain: Barbary galleys in the Mediterranean

_MET_DP827791.jpg.webp)

During the greater part of the 16th century; maritime wars were undertaken with fleets of thirty to forty galleys.[30] The Barbary galleys formed the Western Naval Division of the Ottoman fleets. Their special function was to harm the hereditary enemy, Spain, by ravaging its coasts, destroying its commerce, and providing much needed help to the attempted rebellion of the Moriscos. In this long war, the reïs of Algiers had no rivals; They showed incessant ardor and temerity almost always crowned with success. At a signal from the Sultan, they were seen running forward and fighting in the front ranks, as in Bejaïa, Malta, Lepanto and Tunis, where they acquired the well-deserved reputation of being the best and bravest sailors in the Mediterranean.[31] The severe discipline and care, made the Algiers galley an instrument of war of the first order; the damage that the reis caused to the enemies of the ottoman sultan was so important that spanish benedictin and historian Diego de Haëdo (1555-1613) would say:[32]

Sailing without any fear, they travel the sea from east to west, making fun of our galleys, whose crews, meanwhile, enjoy banqueting in the ports. Knowing well that when their galiotes, so well equipped, so light, encounter the Christian galleys, so heavy and so crowded, the latter cannot think of giving chase, and preventing them from pillaging and stealing at will. They have the habit, to mock them, of tacking, and showing them the stern... They are so careful about the order, cleanliness and layout of their ships, that they do not think about something else, focusing especially on good tie-down, to be able to line and tack well. It is for this reason that they do not have rumbalières... Finally, for this same reason, it is not permitted for anyone, even the son of the pasha himself, to change places, nor to move from where he is.

— Diego de Haedo, Topographia e Historia general de Argel

Atlantic razzias: Hunt for enemy merchant ships

Despite the end of formal hostilities with Spain in 1580, attacks on Christian and especially Catholic shipping, with slavery for the captured, became prevalent in Algiers and were actually the main industry and source of revenues of the Regency.[33] That is why the legendary heroes of Ottoman Algeria were ra'ises (captains of corsair ships) such as Murat Reis the Elder in the 1580s and Hamidou Raïs at the turn of the 19th century. These were men who distinguished themselves through audacious attacks on Christian ships and bringing important prizes to Algiers.[8] French publicist Louis-Joseph Collette de Baudicour wrote: "Algiers had become the firmest support of the Sultans of Constantinople. No event took place in the Mediterranean basin without the Algerian corsairs taking part in it. The main force of the entire Ottoman Navy rested on them".[34]

The Mediterranean was at first the main objective of the action of the corsairs, the reïs rose in the ocean as soon as they had adopted the use of round vessels. Exploring then the roads of India and America, they disturbed the commerce of all enemy nations. In 1616 the Reis Mourad the Younger (Jan Janszoon) plundered the coasts of Iceland, from where he brought back to Algiers 400 captives. In 1619 they ravaged Madeira. In 1631, they caused damage on the coasts of England, blocked the English Channel, and would make catches in the North Sea.[35][36] Algerian pirates naval warfare was intelligent and flexible, but its countermeasures were incredibly clumsy. The Algerians used Xebecs, fast-sailed galleys, to attack individual merchant ships when there was no wind. Algerians usually hid five to seven Xebecs behind a large cliff near the coast, each with at least 100 soldier. A clifftop lookout spotted the European ships and signaled them to approach. Europeans usually surrender quickly when faced with a much superior attacking force. In the case of defense, they usually expected only the death of many sailors and certain defeat.[37]

The reïs pushed the audacity so far as to found in Livorno,[7] with the authorization of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to whom they paid high royalties, a penal colony warehouse, where they came to deposit under the guard of the soldiers of the Grand Duke, the Christian slaves likely to obtain their freedom by means of a ransom. They still had a station at Cape Verde in order to be nearer to stopping the Indian galleons. The Republic of Genoa tolerated for a very long time the traffic in its ports of goods coming from the looting of the reis.[35]

Naval spoils

The spoils of the Corsairs multiplied in the first period of the regency, then began to decrease until they almost disappeared in the eighteenth century, then by the end of the deys period they witnessed a remarkable growth with the attempt to develop the navy and increase its military activity, especially during the period of Europe's preoccupation with the wars of the French Revolution and the conquests of Napoleon. The renewed activity of the Algerian Navy was linked to the efforts of famous sailors, led by Rais Hamidou (1790-1815). the aquittance to the development of the naval spoils from which the state used to take the fifth and distribute the rest to the shipowners who contributed to equipping the fleet is got by reviewing the number of spoils according to the following years:

- 1628 - 1634 : 80 ships were captured during the war against France comprising 1331 people, which made the value of the total spoils in that war rise to about 4,752,000 pounds.

- 1737 - 1799 : the rais took over 376 ships among them 16 Portuguese ships were captured by Rais Hamidou in 1797 along with 118 prisoners. In 1785, some Genoese, Venetian and Neapolitan ships were captured, their spoils estimated at seventy-five million francs.

- 1800 - 1802 : The number of spoils was estimated at 575,152 francs, and 20 ships were seized, of which 19 were Neapolitan, in addition to another Portuguese ship seized by Rais Hamidou, equipped with 44 cannons, and its value was estimated at 194,231.25 francs.

- 1805 - 1815 : The value of spoils was estimated at 8 million francs, of which 1800 were prisoner with 30 ships.

- 1825 : The number of spoils reached eight ships, mostly Dutch, Spanish and English, with an estimated value of about 770415.74 francs.

- 1817 - 1827 : the value of spoils was approximately 700,000 francs.[38]

The Christian captives

When a corsair ship returned to Algiers towing its booty, goods and captives were landed. The pasha would begin to take his share, or a fifth, in addition to the body and tackle of the captured ship, then, the cargo is sold. The slaves not chosen by the pasha were led into the Badestan, a long street closed at its ends, located at the site of the current street of Mahon square in Algiers. There, brokers ran the captives naked, so that the buyers could make their choice. Half of the proceeds from these sales belonged to the outfitting of the capturing vessel: individual, company, reis himself; the other half was divided into shares, of which forty went to the captain, thirty to the agha of the Janissaries on board, ten to the officers, the rest to the sailors and the soldiers.[39]

The number of european christians who fell into captivity in the city of Algiers alone was estimated at about one million people throughout the seventeenth century, equivalent to a quarter of the city's population, numbering at that time about 100,000 people. In the four Beylik prisons that were established specifically for this purpose since 1607, and most of these prisoners were released in exchange for a certain ransom, and some of them converted to Islam, a number of 8000 converted to Islam in 1634 out of a total of 25,000 prisoners, and some of them were integrated into the population and became an active element in society like many of the beleyrbeys who assumed power before the era of the pashas.[40] As for the work that these prisoners carried out, they were divided into social services and economic tasks within the city of Algiers, and agricultural work in the city of Algiers.

Until the use of round vessels in the 17th century, which did away with oars, the reis composed the crews of their galleys, which were generally very low on water, with slaves whom they bought for this purpose, or whom they were procured by capture at sea, or by descent on the Christian coast. The rowers were tied to their benches; there were as many as 300 on a single vessel. When, at the beginning of the 17th century, navigation was practiced entirely by sail, the employment of slaves on corso ships diminished in notable proportions; but the reïs always employed some for the works of strength: turning with the capstan, the towing of the boats, care of cleanliness of the ships, etc.[41]

The number of prisoners varied from year to year. As evidenced by the following table extracted from European sources, which presents aggregate estimates for the city of Algiers according to the following years:[42]

| Year | Number of prisoners | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1580 | 25,000 | |

| 1620 | 35,000 | |

| 1634 | 25,000 | during the war with the King of France (1630 - 1634), 1331 prisoners were captured on the back of 80 French ships |

| 1662 | 21,000 | |

| 1724 | 2000 | |

| 1785 | 6000 | only counting those who were in the prisons of Ali Bitchin Reis |

| 1788 | 2000 | |

| 1816 | 1642 | truce in 1810 AD, followed by the treaty of 1813 AD with Portugal, in which 541 Portuguese prisoners were ransomed for 850,000 Algerian doro |

| 1830 | 122 |

Among the most famous of these prisoners are:

- Greek scientist Petrus Gyllius, captured in the year 1546 while traveling from France to Greece on a scientific mission at the request of King Francis I of France.

- Dominique de Gourgues, the hero of Florida County, captured while traveling from Europe to America (1558).

- Famous Italian painter Fra Filippo Lippi de Madone, imprisoned in 1435

- Italian writer Emmanuel d'Aranda de Bruges, captured while traveling from France to Spain in 1640.

- French comic poet, who wrote the story known as the beautiful Provençal, Jean-François Regnard, captured in 1678.

- Famous Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes (the author of the story of Don Quixote) and the author of the moriscan plays inspired by his memories in Algeria, he remained in captivity in Algeria from 1575 to 1580.

- French scientist Jean Foy-Vaillant was captured in 1674, when he was on a scientific trip to study money, commissioned by King Louis XIV.

- Italian cleric, the priest of the city of Catania, called Caraccioli, captured in 1561.

- Italian poet Antonio Veneziano, captured along with Don Carlo Davagona in April 1578.

- Writer Rene de Bois (Rene de Boys), captured in 1642.[40]

Privateers and enslavement of Christians originating from Algiers were a major problem throughout the centuries, leading to regular punitive expeditions by European powers. Spain (1567, 1775, 1783), Denmark (1770), France (1661, 1665, 1682, 1683, 1688), England (1622, 1655, 1672), all led naval bombardments against Algiers.[43] Abraham Duquesne fought the Barbary pirates in 1681 and bombarded Algiers between 1682 and 1683, to help Christian captives.[44]

Emblems

- Maritime standards of the Regency of Algiers dating from the 18th century

.svg.png.webp) Regency war standard from John Beaumont's album (1705).[45]

Regency war standard from John Beaumont's album (1705).[45].svg.png.webp) Pavilion of the dey of Algiers according to the album by John Beaumont (1705).[45]

Pavilion of the dey of Algiers according to the album by John Beaumont (1705).[45].svg.png.webp)

_A5.svg.png.webp) Type of maritime flag of the regency of Algiers.[46]

Type of maritime flag of the regency of Algiers.[46]_A6.svg.png.webp) Example of a flag used by corsairs of the Algiers regency.[46]

Example of a flag used by corsairs of the Algiers regency.[46]_A9.svg.png.webp) Example of a flag used by corsairs of the Algiers regency.[46]

Example of a flag used by corsairs of the Algiers regency.[46] Type of maritime flag of the regency of Algiers.[47]

Type of maritime flag of the regency of Algiers.[47]_A8.svg.png.webp) A pavilion of the regency of Algiersr[48]

A pavilion of the regency of Algiersr[48].png.webp) A standard of the regency of Algiers[49]

A standard of the regency of Algiers[49]_A4.svg.png.webp) Pavilion of the Regency of Algiers (17th-18th centuries)(B. Dubreuil)

Pavilion of the Regency of Algiers (17th-18th centuries)(B. Dubreuil)

Gallery

A French Ship and Barbary Pirates by Aert Anthoniszoon and Cornelis Bol

A French Ship and Barbary Pirates by Aert Anthoniszoon and Cornelis Bol A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsair by Laureys a Castro (1664–1700)

A Sea Fight with Barbary Corsair by Laureys a Castro (1664–1700) Spanish engagement with Barbary pirates by Andries van Eertvelt (1590–1652)

Spanish engagement with Barbary pirates by Andries van Eertvelt (1590–1652) An English Ship in Action with Barbary Vessels by Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633–1707)

An English Ship in Action with Barbary Vessels by Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633–1707) A Spanish xebec facing two Algerian corsair galiots by Ángel Cortellini Sánchez

A Spanish xebec facing two Algerian corsair galiots by Ángel Cortellini Sánchez Barbary corsairs in action, by Niels Simonsen (1844)

Barbary corsairs in action, by Niels Simonsen (1844)

References

- ↑ Wolf, John Baptiste; Saadallah, Aboul-Kassem (1986). al-Jazāʾir wa-ūrābbā, 1830-1500 (in Arabic). al-Muʾassasah al-Waṭanīyah lil-Kitāb. pp. 131–132.

- ↑ O'Connell, Monique; Dursteler, Eric R. (2016-05-15). The Mediterranean World: From the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Napoleon. Johns Hopkins University Press+ORM. ISBN 978-1-4214-1902-2.

- ↑ Courtinat, Roland (2003). La piraterie barbaresque en Méditerranée: XVI-XIXe siècle (in French). SERRE EDITEUR. p. 23. ISBN 978-2-906431-65-2.

- ↑ Woodhead, Christine (2011-12-15). The Ottoman World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-49894-7.

- ↑ Lowenheim, Oded (2009-05-26). Predators and Parasites: Persistent Agents of Transnational Harm and Great Power Authority. University of Michigan Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-472-02225-0.

- 1 2 Maameri, Fatima (2008). Ottoman Algeria in Western Diplomatic History with Particular Emphasis on Relations with the United States of America, 1776-1816 (PDF). Constantine: Mentouri University. pp. 108–142. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 Burman, Thomas E.; Catlos, Brian A.; Meyerson, Mark D. (2022-08-23). The Sea in the Middle: The Mediterranean World, 650–1650. Univ of California Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-520-96900-1.

- 1 2 Jamil M. Abun Nasr(1971), A History Of The Maghrib In The Islamic Period, p159

- 1 2 Koskenniemi, Martti; Rech, Walter; Fonseca, Manuel Jiménez (2017). International Law and Empire: Historical Explorations. Oxford University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-19-879557-5.

- ↑ Maameri 2008, p. 100

- ↑ Panzac, Daniel (2005). The Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800-1820. BRILL. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-90-04-12594-0.

- ↑ "Moonlight View, with Lighthouse, Algiers, Algeria". World Digital Library. 1899. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ↑ E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936 by Martijn Theodoor Houtsma p. 258 ISBN 90-04-08265-4

- ↑ B. Babaci (30 January 2014). "BABA MERZOUG, histoire d'un exil". Babzman - Information historique et socioculturelle sur l'Algérie. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ↑ Henri Garrot(1910), p381

- ↑ Henri Garrot(1910), Histoire générale de l'Algérie, p380.

- ↑ Henri Garrot(1910), p 382

- ↑ Hrodej, Philippe; Buti, Gilbert (2013-04-25). Dictionnaire des corsaires et des pirates (in French). CNRS. ISBN 978-2-271-07701-1. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- ↑ Albert Devoulx, "La marine de la régence d'Alger", Revue africaine, no 77, septembre 1869, p390

- ↑ Pierre Boyer, "Les renégats et la marine de la Régence d'Alger", Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, vol. 39, no 1, 1985, p94DOI10.3406/remmm.1985.2066

- ↑ Pierre Boyer, "Les renégats et la marine de la Régence d'Alger", Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, vol. 39, no 1, 1985, p95DOI10.3406/remmm.1985.2066

- ↑ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (30 January 2008). Historic cities of the Islamic world. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Tenenti, Alberto Tenenti (1967). Piracy and the Decline of Venice, 1580-1615. University of California Press. p. 81. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Harris, Jonathan Gil (2003). Sick Economies: Drama, mercantilism, and disease in Shakespeare's England. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 152ff. ISBN 978-0-8122-3773-3. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Gregory Hanlon. "The Twilight Of A Military Tradition: Italian Aristocrats And European Conflicts, 1560-1800." Routledge: 1997. Pages 27-28.

- ↑ Jamieson, Alan G. (2013-02-15). Lords of the Sea: A History of the Barbary Corsairs. Reaktion Books. pp. 75–131. ISBN 978-1-86189-946-0.

- ↑ Albert Devoulx, "La marine de la régence d'Alger", Revue africaine, no 77, septembre 1869, p390

- 1 2 تاريخ الجزائر العام للعلامة عبد الرحمن الجيلالي ـ الجزء الثالث: الخاص بالفترة بين 1514 إلى 1830م, p490

- ↑ تاريخ الجزائر العام للعلامة عبد الرحمن الجيلالي ـ الجزء الثالث: الخاص بالفترة بين 1514 إلى 1830م, p491

- ↑ Loades, D. M. (2000). England's Maritime Empire: Seapower, Commerce, and Policy, 1490-1690. Longman. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-582-35629-0.

- ↑ Grammont, H. D. de (1887). Histoire d'Alger sous la domination turque (1515-1830) (in French). E. Leroux. p. 50.

- ↑ Haedo, Diego de (1612). Topographia e historia general de Argel (etc.) (in Spanish). de Cordova y Oviedo. p. 21.

- ↑ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (30 January 2008). Historic cities of the Islamic world. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Baudicour, Louis de (1815-1883) (1853). La guerre et le gouvernement de l'Algérie / par Louis de Baudicour (in French). Paris: Sagnier et Bray. pp. 97–98.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Garrot, Henri (1910). Histoire générale de l'Algérie. Impr. P. Crescenzo. p. 383.

- ↑ Jamieson, Alan G. (2013-02-15). Lords of the Sea: A History of the Barbary Corsairs. Reaktion Books. pp. 75–131. ISBN 978-1-86189-946-0.

- ↑ Ressel, Magnus (6 December 2012). Zwischen Sklavenkassen und Türkenpässen: Nordeuropa und die Barbaresken in der Frühen Neuzeit (in German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 482–484. ISBN 978-3-11-028857-5.

- ↑ Albert Devoulx (1872). Le registre des prises maritimes : document authentique et inédit concernant le partage des captures amenées par les corsaires algériens [The register of maritime catches: authentic and unpublished document concerning the sharing of catches brought by Algerian corsairs] (in French). Alger: Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Littérature et art. p. 111.

- ↑ Garrot, Henri (1910). Histoire générale de l'Algérie. Impr. P. Crescenzo. p. 384.

- 1 2 ناصر الدين سعيدوني (2009). ورقات جزائرية: دراسات وأبحاث في تاريخ الجزائر في العهد العثماني (Algerian papers: studies and research on the history of Algeria during the Ottoman era). الجزائر: دار البصائر للنشر والتوزيع. pp. 137–139.

- ↑ Henri Garrot(1910), p 382

- ↑ Albert Devoulx (1872). Le registre des prises maritimes : document authentique et inédit concernant le partage des captures amenées par les corsaires algériens [The register of maritime catches: authentic and unpublished document concerning the sharing of catches brought by Algerian corsairs] (in French). Alger: Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Littérature et art. p. 111.

- ↑ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (30 January 2008). Historic cities of the Islamic world. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ↑ Martin, Henri (1864). Martin's History of France. Walker, Wise & Co. p. 522. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 Pierre Lux-Wurm (2001). Les drapeaux de l'islam. Buchet-Chastel. ISBN 978-2-283-01813-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Carington Bowles (1783). Bowles's universal display of the naval flags of all nations in the world. Londres.

- ↑ Matthäus Seutter (1732). Atlas Novus : Algercum munita metropolis Regni Algeriani (in German). Augsbourg.

- ↑ B. Dubreuil, Les pavillons des États musulmans, Publications de la Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines de Rabat, 1965, p. 11.

- ↑ Karl-Heinz Hesmer: Flaggen und Wappen der Welt, page 18. Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag, Gütersloh 1992