Chehalis Theater, November 2021 | |

| Former names | Beau Arts Building, Pix Theater |

|---|---|

| Address | 558 N Market Blvd[lower-alpha 1] Chehalis, Washington United States of America |

| Coordinates | 46°39′57″N 122°58′14″W / 46.66583°N 122.97056°W |

| Parking | Street |

| Owner | McFiler's Supernaut LLC |

| Capacity | 450 |

| Screens | 1 |

| Current use | Film, live entertainment, and cuisine |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1923 |

| Opened | December 7, 1938 |

| Renovated | 1938, 1954, 1996, 2016, 2018, 2021 |

| Website | |

| mcfilerschehalistheater | |

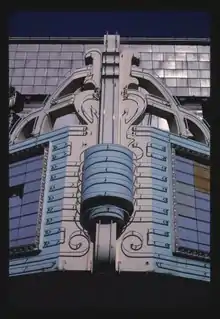

The Chehalis Theater, also as the Chehalis Theatre, is a single-screen, Art Deco movie theater in Chehalis, Washington. The theater is situated at the north end of the Chehalis Historic Downtown District near the Hotel Washington. Known locally for the hand-painted illustrations of popular children's fantasy characters that once populated the ceiling,[2] it is the only surviving movie house in the city.

Since the theater's last renovation that began in 2021, it has been renamed McFiler's Chehalis Theater.

History of theaters in Chehalis

There were numerous early movie houses in Chehalis at the beginning of the 20th century. Most of the theaters were located in the historic downtown area, notably on Market Street and Chehalis Avenue.

Due to the Great Influenza epidemic from 1918 to 1920, movie theaters in the city were shut down for stretches of time. Stricter quarantine laws in Chehalis led to theaters suffering a loss of revenue as potential customers patronized playhouses in other towns and cities in the region that had more lenient rules. A petition in late 1918, requested by theater owners to the city commissioner board, asked that the laws be lifted for theaters and that individuals, rather than the movie houses, be held to isolation standards.[3]

The Orpheum (opened 1908)

The Orpheum Theater, given the moniker "The House of Features",[4] was located in the John West Building in downtown Chehalis. It began operations on November 13, 1907 with the intent to provide films specifically for women and children, relying on independent movies, and charging an admission rate of 10 cents.[5][6][7] supplementing sound by the use of an Auxetophone.[8] The theater also provided vaudeville acts.[9] The entrance was remodeled in late 1908.[10] The business was sold in 1909 and additional renovations were undertaken, including an electric sign[9] and a hand-painted curtain of Mt. St. Helens.[11][12] By the end of 1909, the theater introduced a new steel arch entry and folding chairs for the audience, and upgraded the backdrop by installing a radium curtain.[13] Improvements for fire safety were undertaken in 1910, and the movie house billed itself as showing "clean and moral" productions and using non-flammable film.[14][15]

Due to a lack of space combined with growing demand, the theater owner, Harrison Wheeler, began building a new, $20,000 home for the Orpheum in the downtown district in late summer 1910. Accommodating 750 people, the brick and steam-heated building included a balcony with box seating and large vestibules.[16] The Orpheum remained in its original location and the new building became the Dream Theatre. Wheeler also undertook an expansion of his movie theater business by leasing out a newly built, one-story theater on Market Street that would be separate from the Orpheum.[17] It became known as the Bell Theater and customers would receive a 5-cent coupon to the Orpheum when they attended the new venue.[18][19]

The Orpheum, the first official venue in Chehalis meant for the showing of films, closed in 1912. Despite the appetite for movies in the city and its own need for expansion, Wheeler, in competition of his own making with the Bell and Dream theaters, and also overworked due to his commitments with movie houses in Yakima, Washington, and could no longer keep the Orpheum open.[20] A candy manufacturer would move into the Orpheum Theater space later that month.[21] In 1913, the location was remodeled and became the home of the Empress Theater.[22]

The Vaudette (1908)

The Vaudette was a short-lived movie house, existing for five months from late 1908 to early 1909. Charging a ten-cent admission, the theater was part of a regional branch of theaters and provided opera-style seating.[10][23][24]

Glide Theater (1910)

The Glide Theater was originally a roller skating rink that opened on New Year's Eve, 1908, with a masquerade ball. The maple rink and dance floor was 80 ft × 100 ft (24 m × 30 m).[25] Known simply as "The Glide", it was located at the intersection of Pacific Avenue and Center Street.[26] The interest in roller skating in the city led the Glide to record large attendances and as such, was suspected to be the leading cause of the closing of the Vaudette Theater.[27] Similar to other theaters in Chehalis at the time, the rink also hosted basketball games and vaudeville, and there was an early, opera-style conversion to the building in 1909 so the venue could support live theater performances.[28][29][30] By the end of 1909, a deputy was hired to keep order at the rink.[31]

The first moving picture to be shown at The Glide, in the summer of 1909, was a recording of a Papke-Ketchel prizefight.[32] The theater was upgraded to also be used as a cinema in 1910 and in its first months of operation it continued to host vaudeville and operas. The Glide hosted a minstrel show featuring ballplayers from the Chehalis Gophers.[33][34] The theater was wired to broadcast the Jack Johnson vs. James J. Jeffries fight in 1910,[35] and was converted back into a skating rink during the winter months.[36][37] A fire in 1911 destroyed a $3,000 newly installed electric organ.[38]

Beginning in 1911, the theater was used as a basketball court for the Chehalis high school boys team for several years.[39][40] Wrestling matches were also held at the theater.[41] The Glide, starting in 1914, was utilized as a gymnasium during the school week for young people, particularly Chehalis high school students. Showers and basketball equipment were installed.[42][43]

By 1915, the theater changed ownership but remained operational as a skating rink.[44] The Glide, in 1916, was host to the creation of the People's Independent Party, a political group meant to oust leaders, particularly those in judicial roles, in Lewis County, Washington.[45] The Glide ceased to exist by January 1917, bought out to become an automobile repair garage. The rink floor and the opera-style additions were removed.[46]

The Dream Theater (1911)

The Dream Theater was originally meant to be an expansion of the Orpheum but became a new theater in its own right.[16] Located in the historic Hotel Washington on Market Street, the new movie house was intended to be called the Gem Theater. It was built with an asbestos-lined ceiling and a rear exit, both early concerns about fire safety at the time, and had an occupancy of 400. A retreating lobby to the hotel, still in existence as of 2023, was put in place during the build.[47] The name was changed and it became known succinctly as "The Dream".

The theater opened in January 1911 with a showing of 4,000 feet (1,219.2 m) of film backed by a four-piece orchestra. It contained a large amount of globe lights at its entrance, had opera-style seating, the building was steam-heated, and boasted of being fireproof, modern touches and concerns of the era.[48][49] Original admission was listed as between 5 and 15 cents.[50] By the end of its first year, The Dream partnered with the Cyclohomo Amusement Company and in 1912 a small enlargement of the theater space was begun;[51][52] additional electric globe lighting was installed in 1913.[53] The Dream hosted vaudeville and live musical performances, and once held a competition to capture a greased pig.[54]

The venue was threatened with the loss of its license in 1914 after several notices of disturbance were brought forth by the Hotel Washington due to the noise level of the electric organ in the theater.[55] In 1915, the theater owner since its inception, J.D. Rice, began operating the Bell Theater in association with The Dream.[56] Later that year in December, a service crew from the local St. John's Garage assembled a Ford automobile inside the theater. Taking two minutes and 44 seconds, the attempt broke a Seattle crew record of a type of event common at the time that showcased the Ford's ease of build.[57][58] A performance by the renowned dancing couple, Vernon and Irene Castle, took place at The Dream in 1916.[59] In the summer of that year, the theater upgraded to a second projector, mitigating reel-changing delays during the showing of a film.[60] The movie house held a fundraising concert in early 1917 for a local military company at the onset of the country's entry into World War I.[61]

In 1917 and 1918, the theater contracted, for $4,000 and over $5,000 respectively, to show films exclusively by Artcraft and Paramount Pictures.[62][63] The movie house shut down for several weeks during 1918 due to the 1918–1920 flu pandemic.[64] Seeing that the entertainment economy of Chehalis and The Dream could expand, Rice purchased a lot in 1919 with the intent to build a $200,000[65] combined movie and theater playhouse[66] that would have a suction ventilation system installed, and the theater planned to contain a balcony with a total house occupancy of 850.[67] After several years, the new theater did not come to fruition, instead a building was constructed that hosted an automobile garage.[68]

Rice faced several lawsuits and legal troubles during his run as proprietor of The Dream. He pled guilty to paying a woman ticket seller significantly less than minimum wage in 1916[69] and admitted before a city commission in 1919 that he broke an ordinance by seating patrons in the aisle during an overflow showing.[70] A $10,000 lawsuit was brought against Rice in 1920 for injuries sustained from a worker falling from a ladder at the hotel.[71] Along with several others in the region, he faced a copyright lawsuit in 1920, specifically for playing the song, "Let The Rest Of The World Go By", at The Dream.[72]

In 1926, after the loss of the Liberty Theater to a fire, the Dream Theater changed ownership and renamed itself the Liberty Theater. The electric sign that adorned the lost Liberty playhouse was moved to The Dream's location and became the new marquee.[73] In 1927, under the ownership of the Twin City Theatres Company, The Dream, along with the St. Helens Theater, was part of a $1.0 million United Theatres Company contract to purchase local and regional movie houses.[74]

After the sale, The Dream closed in 1930 due in part to competition from Centralia's new Fox Theater and the space remained unoccupied until the end of the year when a new venture, given the title the Peacock Theater, planned to open after extensive remodeling.[75][76]

As of 2023, a ghost sign of the Dream Theater is visible on the front entrance side of the Hotel Washington.[77]

The Bell Theater (1911)

Originally an expansion of the Orpheum, the Bell Theater was a brand-new, one-story theater on Market Street.[17] A coupon redemption between the two playhouses allowed a 5-cent discount to the Orpheum when customers attended the Bell.[18]

The Bell opened on February 20, 1911. With admissions listed at 10 cents for children, 15 cents for adults, patrons enjoyed opera-style seating. The ceiling was covered in metal decor and the venue owners, the Wheeler family, boasted of fire exits and two acts to be performed each evening. The first acts were a comedic performance by the pair known as "Bell and DeBell" and a juggler under the moniker, "Dalbenie".[18] By the next month, Wheeler, promising to run a clean theater, allowed an act deemed "little less than vulgar" to perform only once and the Bell was given the motto, "The House of Good Shows".[78][79] Wheeler advertised that the Bell and the Orpheum were capable of running a variety of film productions, including Edison, Pathé, and Vitagrapgh.[80] Similar to other playhouses in the city, the Bell provided vaudeville acts[81] but by autumn of 1911, the Bell changed its programming to movies and musical comedy acts. The building footprint was slightly increased and the stage enlarged for the changes in programming.[82]

After the closure of the Orpheum in 1912, Wheeler was to continue to own the Bell[20] but sold his position to Mr. D.I. Moore, who promised renovations and a return of vaudeville, a few weeks later.[83] In the summer of that year, a thief twice stole from the theater wardrobe of the Bell during a spree encompassing the Twin Cities.[84] In 1913, the Bell underwent several changes regarding ownership, partners, contracts, and management. The theater building was sold in April to W.H. Twiss, who owned it until its end, and he planned to make improvements,[85] but J.D. Rice, owner of The Dream, was announced as manager for the Bell a week later where he would add additional lighting for signage similar to The Dream.[53][86] In November, a new owner of the theater's productions, Arthur Winstock, reopened the Bell after some remodeling and renamed the venue as the People's Theater. Vaudeville and moving pictures were announced as the programming, with admissions spanning from to ten to thirty cents.[87] Within six weeks, Winstock married Isla Rolsom, the Bell's ticket seller, and then absconded from the city without her, having paid little of his debts or promises regarding the People's Theater.[88] The Bell restarted operations soon thereafter, and resumed using its original name.[89]

With the Bell running smoothly after the difficult year, a contract to show films by the Famous Players Film Company was reached in early 1914. The deal was considered the most expensive in Chehalis at the time.[90] After receiving permission from the city police commissioner, the Bell was allowed to show the forced prostitution film, Traffic in Souls, in the summer.[91] Management changed once again. Overtaking from Mr. T.C. Grindley in mid-1914, the new production owners, Proffitt and McDevitt, stated their intentions to improve the lighting and make upgrades to the curtain and machinery.[92] In October, the Bell held a raffle in conjunction with the Central Theater in Centralia to give away several prizes, including a 1915 Buick and diamonds, meant specifically to entice women and girls to participate. One winner received the right to donate a Kimball organ to a place of their choosing.[93]

In early 1915, the Bell underwent new management by the Brin theater chain, who also owned the Central. Similar to previous overseers, renovations were announced.[94] Mr. Rice ceased being the operator of the Bell in late January 1916 after having kept the theater open part-time during the prior year.[95][96] He would regain oversight a few months later.[56] A small fire that was deemed arson, and connected to other mysterious fires in the downtown business district, took place at the Bell in February. Causing minor damage totaling $50, the stage was charred and some seats were burned.[96]

A suspected failure of a pump in March 1916 led to the Bell's floor and pit and stage areas to be submerged in water. The flooding was severe enough to come with 15 feet (4.6 m) of the entrance doors despite the inclined floor.[97] The owner, Twiss, made repairs but suggested he would turn the building into a business store instead.[98] By July, the building was partially rented out to a bicycle and motorcycle repair shop.[99] The repair shop bought out the Twiss interest in January 1917, which had by that time rented out space for a tailoring business.[100]

The Empress and the New Liberty Theaters (1913)

The Empress opened on October 10, 1913[101] at the location of the old Orpheum Theater. The building was remodeled with a new backdrop and film machinery, and was upgraded to include opera-style seating. Before the opening, the owners held a naming contest for the new playhouse, geared specifically for Chehalis women to participate; the moniker of The Empress was chosen.[22][102] The proprietors charged ten-cents and it was an entertainment venue for silent film, photoplays and live music.[103]

The showing of the 1916 flim, Purity, at the playhouse led to a threat of a warrant after the movie was deemed immoral; the Empress did not present the film further.[104] A Kimball two-manual pipe organ, built by the Johnson Pipe Company of Los Angeles, was installed in 1917.[105][106]

In 1918, the Empress Theater name was changed in favor of the New Liberty Theater during a renovation. The viewing area was enlarged after the upper story of the building was torn out to provide a balcony for an opera-style arrangement.[107][108] The occupancy was increased to 500, which included spring cushioned seating, considered modern at the time. Installed during the renovation was an intricate, coordinated lighting system and the remodeled movie house was noted for its colored glass panels and stucco reliefs. Equipped in the new theater was a $5,000 pipe organ and the ceilings were built in a fashion to highlight the sound. The name shortened to the Liberty Theater, it officially opened on July 11, 1918 with ownership eventually transferring to a local movie house business, the Twin City Theatres Corporation.[109] In 1920, an advanced electric heating system was installed[110] and the organ was renovated with additional pipes.[111]

The Liberty remained in operation until the summer of 1926, when it was destroyed in a fire.[109] The fire began around midnight on July 19th and was believed to be of "incendiary origin". The disaster was a combined loss of $13,500 to the theater itself and the building, including destruction of the pipe organ.[112] Less than a month later, the Twin City Theater Company decided not to rebuild the Liberty Theater and the owner of the structure, Chehalis mayor John West, converted the building into a lodge and a business store.[113] The lighted marquee would be moved to the Dream Theater that September, and The Dream was renamed the Liberty.[73]

St. Helens Theater (1924)

The building occupied by the St. Helens Theater was originally utilized as a Ford dealership that also provided a gas station. Known as the St. John's Garage, the dealership and theater was owned by Arthur St. John, who also had ownership stakes for several years in The Dream and Liberty theaters.[114] The brick-and-tile Italian Renaissance style theater, after a $100,000 renovation, opened on May 12, 1924 and had an occupancy of 850 and was home to a Kimball organ.[115][116][117] Billed as the "House of Hits",[118] the theater's first film shown was Sporting Youth.[116]

While the movie house presented films, it was used as well for live theatrical performances. The playhouse was under the ownership of the Twin City Theater Company, and along with the Dream Theater in 1927, the St. Helens was sold to the United Theatres Company as part of a $1.0 million purchase of theaters in the region.[74] The theater closed in 1954[119] and the balcony sealed off and converted to office space.[115] The final films that the St. Helen's Theater offered was the last Disney-released RKO Radio Pictures film, Rob Roy: The Highland Rogue, and the war film, El Alamein.[120]

The site was remodeled beginning in 2008 and converted into a rental venue that restored large parts of the original theater footprint and fixtures.[115] A ghost sign for the Chehalis Bee-Nugget newspaper was found during the remodel and was preserved.[121]

Peacock and Grand Theaters (1930)

The Peacock Theater, named after its owner, opened at the location of the closed Dream Theater with plans to be operational in late December 1930.[75][76] Remodeled and installed with film projectors and sound equipment to play talkies,[122] the theater formally opened on January 3, 1931 and the first feature was the Amos 'n' Andy film, Check and Double Check. Initial admission charges were 10 cents for children, 25 cents for adults, and the venue provided matinee and evening showings.[123] A ventilation system to provide more comfort during warmer weather was installed at the Peacock a few months later.[124] In September 1931, the frying pan used to cook a record-setting omelet earlier that summer at the local Alexander Park was displayed at the Peacock and films that recorded the event were shown.[125][126] In partnership with a local bakery, the theater hosted a doughnut eating contest for children at the end of the year.[127]

The Peacock closed briefly in 1933 for renovations of both the interior and exterior of the building. It reopened in November with a showing of the film State Fair and a policy was introduced to primarily showcase new movies and second screenings of popular films.[128] The Peacock family sold the theater in January 1934 to the Twin City Theatre Company. The Peacock was renamed the Grand Theater, or more simply as The Grand, by March.[129][130][76]

The Grand hosted Bank Night during the Great Depression, a popular game of chance that was widely available in rural areas despite pressures to ban the gambling events. During the height of bank nights, the film venue, with an occupancy of 284,[76] once reached an overflow capacity of 500 people.[131] Despite a ten-year lease signed in 1938 to continue The Grand at the Hotel Washington, the theater was closed in 1940.[76]

Yard Birds Cinema

The Yard Birds Mall, located at the very northern limits of the city of Chehalis, had several movie theater operations over the course of its existence. The first theater, referred to as Cinema 3, was built and opened in 1982.[132] It held three screens and encompassed 7,500 square feet (700 m2).[133] Operators such as Luxury Theatres, Act III, and Regal Cinemas would oversee operations for stretches of time.[134] The Act III ownership ended after the flood of 1996.[135] Regal did not renew their lease in 2002, at which time the cinema went into private ownership.[133]

The new owner, Daryl Lund, also owned the Chehalis Theater concurrently. There were plans in 2003 to expand the footprint to 8 screens, with a total occupancy of approximately 1,000 people. The $1.5 million project did not materialize but the theater did complete work on improvements for sound and layouts to the existing area. It was at this time that the owner and his partners began to refer to the Yard Birds location as the Chehalis Cinemas, a name Lund would also give to the Chehalis Theater.[133] Similar to the Chehalis movie house, the Yard Birds Cinema 3 struggled in its competition with the larger Midway Cinema at the Lewis County Mall, located directly north, and it shut down in March 2009.[136] A group focused on providing Spanish-subtitled films to the local populace opened the screens in May, providing a concessions stand geared more towards Latin foods,[136][137] but the new venture failed to draw audiences, closing six months later in October 2009.[138] No theater operated again in the mall and Yard Birds was permanently closed in 2022.[139]

History of the Chehalis Theater

A wood structure that housed a horse livery and stable occupied the site as far back as 1907.[140][141] The building was constructed in 1923 and was originally named the Beau Arts Building.[142][143] First home to a Ford car dealership, the location became known as St. John's Garage[142] and the Chehalis Garage.[119]

After the structure was renovated to become a movie house, it opened on December 7, 1938, as the Pix Theater, seating 653;[142][143] the first film shown was Bob Hope's Thanks for the Memory.[144][145] A large newspaper spread in The Centralia Daily Chronicle was printed welcoming the theater. The Twin City Theatre Company, under the direction of Arthur St, John, were the owners of the new movie house and promised to provide first and second-run movies at "popular prices".[145]

The Pix originally had a triangular marquee with fluorescent lighting.[145] The theater's initial decor included a lobby with red and blue carpeting, and the theater viewing area, equipped with a balcony,[145] had red silk lined, blue-and-gold fleur-de-lis accented walls, red velour seats, and women had access to a cosmetic room.[140][145] The building had air conditioning, was fireproofed, and great measures were taken to provide clear sound and viewing angles.[145] A pipe organ was initially installed but was relocated and rebuilt after an unknown time to a church in Fremont, Seattle.[146] Typically shown at the theater during its early beginnings were a sequence of newsreels, cartoons, and westerns.[147]

The building sustained damage during the 1949 Olympia earthquake but continued to operate.[119] Closed for a short time in 1953,[141] it was named Chehalis Theater in 1954 after a brief renovation during its closure.[140][142][lower-alpha 2] The remodel included a new screen that could show a variety of film productions, including CinemaScope and 3-D.[1] A marquee from the St. Helen's Theater in Chehalis would be added to the building facade during the project.[1][148] The Roewe family owned and operated the theater in the 1970s and the movie house was run by a theater chain for a time, projecting films until 1988.[141][142]

Due to economic hardships and maintenance backlogs, the theater shut down and became a video rental store named Video Time.[142] During this period, several murals of children's cartoon characters were painted on the ceiling.[135] After the theater was sold in 1994 to Daryl Lund, also the owner of the Yard Birds Cinema 3 at the time,[133] it hosted a flea market and Lund would refer to both the Cinema 3 complex and the Chehalis Theater as the Chehalis Cinemas.[141][142] Lund leased the theater to Jerry Rese who began a large restoration in 1996, finding and reusing decor and machinery stored at the theater. The movie house at the time listed the screen to be 16 ft × 32 ft (4.9 m × 9.8 m) and the venue had a footprint of 5,000 square feet (460 m2).[135] The interior had a green decor and Rese removed the original patterned theater carpeting. He installed 298 seats that were original to another closed theater and had the concession stand in the lobby rebuilt. There were plans to reopen the playhouse as a second-run theater.[135] The marquee was restored in 2000.[141]

The independent movie, The Immigrant Garden, premiered at the theater in 2001.[149] There were brief periods of screening films into 2008, including some new releases, when the location ceased operations until 2016 due to competition with the larger, upgraded Midway Cinemas at the Lewis County Mall.[142][147][150][151]

In 2003, the Chehalis Historic Preservation Commission awarded the Chehalis Theater with a listing and plaque recognizing the historical importance, and restoration efforts, of the movie house.[140][141]

2016 and 2018 renovations

The first renovation began in 2016 after a new owner leased the building to a local proprietor. The theater contained original and antique film machinery, including a toilet in the projection room, and the balcony was intact.[119] The restorations focused on reviving and saving much of the Art Deco style,[143] while adding an upstairs bar, dining area, and kitchen. The theater began film showings, and added musical acts and screenings of Seattle Seahawks games for residents.[147] The cartoon murals on the ceiling, added at an unknown time but not original to the theater, were preserved owing to the community support for the work. The occupancy was listed as 285.[119]

In late 2018, a new lease agreement with a local Chehalis family led to additional renovations. The owners continued to screen movies and provide live musical entertainment while concentrating on pizza as the main cuisine option.[152]

2021 renovations and reopening

In 2020, a local restaurateur bought the theater and started the third restoration in five years in 2021. Renaming the location as McFiler's Chehalis Theater, early plans included a reopening later that year or early 2022, with the expectation to continue to screen movies while providing restaurant dining and live entertainment. Adhering to ADA requirements and new building codes, extensive remodeling was done to large portions of the theater, including a modified marquee. The ceiling illustrations were to be painted over but photographed and displayed along with antique equipment from the building.[2]

The theater had a soft opening in late 2022,[2] and an official ribbon-cutting ceremony took place in March 2023.[153] The theater, since its reopening, has hosted events tied to the 75th anniversary of the Kenneth Arnold UFO sighting[154] and a symposium on Bigfoot that included speaker Cliff Barackman.[155] The theater hosted the first Northwest Flying Saucer Film Fest in 2023, coinciding with the city's Flying Saucer Party.[156]

As of 2023, the Chehalis Theater listed an occupancy of 450[157] and was opened to fine dining, comedy shows, musical performances, charity events, live televised sports, and film presentations.

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 "Movie House Due Chehalis". The Daily Chronicle. August 6, 1954. p. 1. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Fitzgerald, Emily (June 16, 2021). "Renovations Ramp Up at McFiler's Chehalis Theater". The Chronicle. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ↑ "Discussion Of The Influenza". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 20, 1918. pp. 1, 12. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "T Stands For Theatre". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 21, 1911. p. 4. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

Advertisement

- ↑ "Chehalis And Vicinity". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 15, 1907. p. 5. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "The Orpheum Attracts". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. July 30, 1909. p. 1. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 15, 1909. p. 7. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "The Auxetophone". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 16, 1909. p. 1. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- 1 2 "Theater Giving Fine Shows". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 7, 1909. p. 7. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- 1 2 "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 11, 1908. p. 7. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Local News". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 5, 1909. p. 5. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Local News". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 30, 1909. pp. 4, 5. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 26, 1909. p. 10. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Improving the Orpheum". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 11, 1910. p. 5. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 23, 1910. p. 9. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- 1 2 "Modern Opera House On Park". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 16, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- 1 2 "New Brick Block Will House a Picture Show". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 25, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Another Theatre Ready". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 17, 1911. p. 9. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 24, 1911. p. 9. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- 1 2 "The Orpheum Theater Closes". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 7, 1912. p. 7. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Candy Manufacturers". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 14, 1912. p. 7. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- 1 2 "Another Picture House Here". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 12, 1913. p. 4. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Local News". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 15, 1909. p. 5. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ The Chronicle staff (September 9, 2018). "Toledo Man Gets 3 Years in Prison in 1998". The Chronicle. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "K. of P. Masquearade Ball". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 25, 1908. p. 6. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Local News". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 18, 1908. p. 7. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Large Crowds Attend 'The Glide' and Enjoy Excellent Skating". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 5, 1909. p. 3. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Vaudeville at The Glide". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 19, 1909. p. 8. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 9, 1909. p. 7. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Change to Opera House". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 28, 1909. p. 2. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "More Arc Lights Wanted". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 3, 1909. p. 12. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. August 20, 1909. p. 5. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "New Lease". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 4, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Minstrel Show For Ball Boys". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 15, 1910. p. 3,11. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Report of the Fight". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. July 1, 1910. p. 13. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 10, 1914. p. 11. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 19, 1913. p. 5. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Chehalis Fire Damages Glide, Destroys Organ". Centralia Weekly Chronicle. April 12, 1911. p. 4. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "High School Basket Ball". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 24, 1911. p. 9. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Abandon The Gymnasium Plans". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 3, 1913. p. 2. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Nelson Wins Wrestling". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 19, 1912. p. 8. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Getting Ready For Gymnasium". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 4, 1914. p. 2. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "The Next Thing To A Gym". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 11, 1914. p. 2. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 19, 1915. p. 11. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "A New Ticket In The Field". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 15, 1916. p. 5. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Chehalis Has Big New Garage". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 26, 1917. p. 3. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Another Moving Picture Show". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 6, 1911. p. 3. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Will Open Next Week". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 20, 1911. p. 10. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "At the Dream Theater". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 17, 1911. p. 8. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Pictures of Memories". Centralia Daily Chronicle. May 30, 1964. p. 7. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

Photo of the Dream Theatre

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 2, 1911. p. 5. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Untitled". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 4, 1912. p. 8. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- 1 2 "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 30, 1913. p. 9. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "A Musical Treat". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 27, 1914. pp. 5, 10. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "City Dads Don't Appreciate Theater Music". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. July 17, 1914. p. 1. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- 1 2 "Veto Overridden". The Chehais Bee-Nugget. March 5, 1915. p. 1. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Local Ford Crew Has Record". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 10, 1915. p. 2. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ The Fordowner - Remarkable Vaudeville Stunt. Hallock Publishing Company. March 1916. p. 26. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "At The Dream Theatre". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 5, 1916. p. 6. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Untitled". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. August 25, 1916. p. 9. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Help Company M Boys". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 30, 1917. p. 1. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "$4000 Worth Of Pictures". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. August 24, 1917. p. 11. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 20, 1918. p. 9. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Dream Theater Open Again". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 15, 1918. p. 8. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "A Bright Outlook For 1920 For The People Of Chehalis". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 9, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Chehalis to Have New and Modern Playhouse". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 21, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Planning For New Theater". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 16, 1919. p. 10. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "New Garage Under Way". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 16, 1924. p. 15. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ Second Biennial Report of the Industrial Welfare Commission (Washington state). Frank M. Lamborn Public Printer. 1917. pp. 92–93.

- ↑ "More Paving Resolutions". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 28, 1919. p. 1. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "J.D. Rice Sued For $10,250". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 9, 1920. p. 7. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Pleasing Music Causes Lawsuit". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 1, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- 1 2 "Town Talk - Theater Name Changed". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 17, 1926. pp. 11, 16. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- 1 2 "$1,000,000 Theater Deal Interests Local People". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 29, 1927. p. 13. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- 1 2 "New Theater to Open Here This Month". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 5, 1930. p. 1. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pierce, Ron. "Grand Theatre". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ Peredina, Graham (December 1, 2017). "128-Year-Old Hotel Washington". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 10, 1911. p. 5. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 24, 1911. p. 7. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Announcement". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 5, 1911. p. 3. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Local Grls in Vaudeville". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 19, 1911. p. 9. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Musical Comedy Is Coming". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 19, 1911. p. 2. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Change In Bell Management". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 21, 1912. p. 3. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "One Haul Is Not Enough". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. August 1, 1912. p. 2. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "W.H. Twiss Buys Bell". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 18, 1913. p. 3. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Bell Again Changes". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 25, 1913. p. 2. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Bell Theater To Be Re-Opened". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 7, 1913. p. 10. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Theater Man To Other Climes". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 19, 1913. p. 12. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Bell Theater". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 26, 1913. p. 4. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "At the Bell Theater". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 20, 1914. p. 7. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "White Slave Picture Tonight". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. June 5, 1914. p. 7. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Bell Theater Sold". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. July 31, 1914. p. 2. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "To Give Away $2200 In Prizes". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 16, 1914. p. 5. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Brevities of the Business". Motography - Expoliting Motion Pictures (Vol. XIII, No. 9 ed.). February 27, 1915. p. 334. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 28, 1916. p. 5. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- 1 2 "Looks Like Fire Bug's Work". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. February 4, 1916. p. 1. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 31, 1916. p. 11. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 7, 1916. p. 9. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. July 28, 1916. p. 7. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Roy Sullivan Buys". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 19, 1917. p. 1. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "The Empress Anniversary". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 9, 1914. p. 4. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 26, 1913. p. 5. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ "Who's Who In Our Fair City". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 12, 1913. p. 4. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Purity Vs. 'Purity'". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 20, 1916. p. 8. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Empress Pipe Organ Here". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 6, 1917. p. 10. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Big Pipe Organ Now In Use". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 20, 1917. p. 3. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "The New Liberty Theater". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. May 3, 1918. p. 9. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ↑ "To Modernize The Empress". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 19, 1918. p. 1. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- 1 2 Flom, Eric L. (December 5, 2007). "The Liberty Theatre in Chehalis opens on July 11, 1918". HistoryLink. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 5, 1920. p. 7. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Business Locals". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. October 29, 1920. p. 5. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Fire Damages The Liberty". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. July 23, 1926. p. 7. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ↑ "The Twin City Theaters Sold - Discontinue Liberty Theater". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. August 13, 1926. p. 1. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ↑ Skinner, Andy (February 12, 2018). "Arthur St. John Helped Lewis County Usher in the 'Era of the Auto,' Flight". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

From the Chronicle's archives

- 1 2 3 Tomtas, Justyna (March 21, 2017). "Former St. Helens Theatre in Chehalis to Open as Event Center". The Chronicle. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- 1 2 Flom, Eric L. (January 26, 2003). "St. Helens Theatre in Chehalis opens on May 12, 1924". HistoryLink. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ "St. Helens (Fox) Theatre - 2/6 Kimball". Puget Sound Pipeline. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ McDonald-Zander, Julie (2011). Images of America - Chehalis. Arcadia Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9780738576039. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nailon, Jordan (May 26, 2016). "The Show Will Go On at the Chehalis Theater After Sale". The Chronicle. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ Krefft, Bryan. "St. Helens Theatre". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ Pittman, Mitch (March 31, 2017). "'It's a labor of love:' Old Chehalis theater gets new life". KOMO 4 News (Seattle, Washington). Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Peacock Theater Work Making Progress". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. December 19, 1930. p. 17. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Peacock Opens Here Saturday, Jan. 3". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 2, 1931. p. 1. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Town Talk". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. April 17, 1931. p. 11. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "See Chehalis Big Frying Pan". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. September 18, 1931. p. 16. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ Mittge, Brian (September 20, 2006). "75 years ago, in 1931 - Famous Omelet". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Untitled". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 1, 1932. p. 11. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Peacock Theater To Reopen Its Doors Friday". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. November 10, 1933. p. 1. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Town Talk". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 19, 1934. p. 5. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "News From Chehalis Avenue Merchants". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. March 16, 1934. p. 6. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Karl Willrich Protests Bank Night In Theaters". The Chehalis Bee-Nugget. January 15, 1937. p. 3. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ↑ Layton, Ken. "Yardbirds Cinema 3". Cinema Tour. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Emerson, Amy (April 15, 2003). "$1.5 million expansion planned at theater". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ↑ Coursey, John. "Cinema 3 at Yard Birds". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Pfeifer, Larissa (June 20, 1996). "Theater Rebirth". The Chronicle. pp. 49–50. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- 1 2 Mittge, Brian (April 4, 2009). "Theater Shuffle May Bring New Options". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ↑ Decker, Sharyn L. (May 1, 2009). "Spanish-English Cinema Opens in Chehalis". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ↑ Allen, Marqise (October 30, 2009). "Yard Birds Mall Theater Closes…Again". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ↑ Vander Stoep, Isabel (June 5, 2023). "Applicant Eyes Demolishing Yard Birds Shopping Center for New 622,167-Square-Foot Warehouse". The Chronicle. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Emerson, Amy (May 10, 2003). "Chehalis honors property owners". The Chronicle. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Emerson, Amy (May 10, 2003). "Hometown Proud". The Chronicle. pp. 21–22. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Nailon, Jordan (October 6, 2016). "Chehalis Theater Draws a Crowd Once More". The Chronicle. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Historic Theatres - Statewide Survey and Physical Needs Assesment" (PDF). dahp.wa.gov. WA State Dept of Archaeology & Historic Preservation.

- ↑ Layton, Ken. "Chehalis Theater". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "New Chehalis Theater To Open Tomorrow Night". The Centralia Daily Chronicle. December 6, 1938. p. 2. Retrieved November 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Chehalis Theatre 2/8 Wicks Robert Morton". Puget Sound Pipeline. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Carlson, Greg (December 21, 2016). "The Chehalis Theatre: A Historical Building Lives On". Lewis Talk. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ↑ Felthous, Dave. "Chehalis Theatre". cinematour.com. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ↑ Paulu, Tom (May 21, 2001). "A Touch of Hollywood in Chehalis". The Daily News (Longview, Washington). Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ↑ Brewer, Christopher (January 15, 2015). "For Sale: One Theater, Asking Price $299,000". The Chronicle. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ↑ Allen, Marqise (January 6, 2009). "Chehalis Cinema Closes". The Chronicle. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ↑ Hayes, Katie (December 20, 2018). "New Managers Take Over Chehalis Theatre, Plan to Host Live Entertainment, Serve Pizza". The Chronicle. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ↑ Wenzelburger, Jared (March 6, 2023). "A Ribbon-Cutting Ceremony Held for McFiler's Chehalis Theater". The Chronicle. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ↑ Sexton, Owen (September 19, 2022). "Chehalis Celebrates 75th Anniversary of 1947 Historic UFO Sighting With Flying Saucer Party". The Chronicle. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ↑ Sexton, Owen (April 17, 2023). "Hundreds Attend 'Bigfoot: Real or Hoax?' Event in Chehalis". The Chronicle. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ↑ Sexton, Owen (September 28, 2023). "Inaugural Northwest Flying Saucer Film Fest in Chehalis showcases 19 short films". The Chronicle. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Emily (February 8, 2023). "HUB Comedy and McFiler's Chehalis Theater Partner to Bring Big Name Acts". The Chronicle. Retrieved June 5, 2023.