The early 1900s saw many calls for the British Empire to adopt a new flag representative of all its dominions, Crown colonies, protectorates, and territories. Such a role was already fulfilled by the Union Jack of the United Kingdom, but some regions of the empire were beginning to develop distinct national identities that no longer seemed appropriately showcased by that flag alone. For example, after achieving self-governance, Canada used a British ensign defaced by its coat of arms as a flag to represent itself internationally.[1] Other regions such as Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa began using similar flags as they gained autonomy as well.[2] Although the Union Jack in the canton of these flags still felt like a natural inclusion by their primarily white settlers, who considered the United Kingdom to be their homeland, it was becoming clear to some that the growing status of all these new nations deserved to be highlighted in some form. This led to the creation of many Empire flags, which saw widespread use from the beginning of the reign of George V to the end of the Second World War.[3]

Views on using the Union Jack

.svg.png.webp)

What made the British Empire unique among its contemporaries was that it resembled an association of nations rather than a highly centralized state. The laws and institutions of each constituent territory did not necessarily recognise the existence of a wider empire. It was pointed out at a 1914 series of lectures on the governance of the British Empire at King's College that there was no common currency in circulation, record of marital status, or process of naturalization. The Union Jack also did not function as a true Empire flag as far as the law was concerned. Each of the territories of the empire were simply possessions of a common monarch. Despite the legislative supremacy of the United Kingdom, colonial opinions were moving toward seeking institutional equality while still recognizing a shared existence under the Crown.[4]

In regard to opinions on the Union Jack specifically, a 1924 article in Australia declared that there being a British Empire flag was a misconception. The flag was pointed out as being designed for Great Britain and Ireland specifically, and that use of it elsewhere was highly restricted. Even the governor general of a dominion could not fly the flag without defacing it with their emblem. Those in the army had to deface the Union Jack if it formed part of their regimental colours, and the Royal Australian Navy could not use it as well. Soldiers of the British Army were alleged to have the privilege to remove the Union Jack wherever it was flown inappropriately, but this was not ever exercised. The article went on to encourage Australians to use their own flag, as it was "an act of grace and love" for the monarch to have provided them with one unique to them. It argued that it was not an act of disrespect to fly it in place of the Union Jack when it was already included in the design.[5]

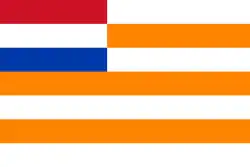

Observations on the Union Jack not being representative of the empire saw support from Prime Minister Hertzog of South Africa in 1926 when his government was considering a new national flag. He believed the Union Jack was only being flown in the dominions due to historical precedence, and that it was really just the flag of the United Kingdom in actuality. At the time of these remarks, Hertzog appeared to suggest that the incorporation of the Union Jack into the new South African flag was not necessary, despite stating that he wished to maintain good relations with the rest of the empire.[6] Many designs under consideration ended up not featuring the Union Jack in them at all, with some opting to instead make references to the Boer republics.[7]

The views held by Hertzog were soon echoed by others. An article in the Southern Cross weekly newspaper argued that the Union Jack became an anachronistic symbol after the establishment of the Irish Free State. It also questioned why the dominions recognized the United Kingdom in their flags through the Union Jack without any form of reciprocation being granted to them. Maxwell Garnett, general secretary of the League of Nations Union, suggested altering the Royal Standard of the United Kingdom to include dominion symbols as one possible solution for that issue.[8]

An article in the Southern Mail from later in 1926 indicated that some Australians of the time had already begun to think of the Union Jack as a foreign symbol. The author spoke of a man who referred to the Union Jack as the symbol of a united England, Scotland, and Ireland rather than the entire British Empire. What followed in the text was a rebuttal, claiming that Australians did not see the Union Jack as a flag of servitude. Nonetheless, the author still supported those choosing to fly the Australian flag itself, as it was a privilege granted by the British.[9]

In 1946, Prime Minister Mackenzie King of Canada issued instructions that the Canadian Red Ensign be flown on all public buildings rather than the Union Jack to prepare for the adoption of a new national flag at a later time. This was met with widespread controversy. William Duff, a senator from Lunenberg, had sent a telegram in protest. He argued that the Union Jack would remain the only appropriate flag to fly so long as Canada remained part of the British Empire, and that the Canadian Red Ensign was best used by private individuals.[10] The Union Jack has maintained a ceremonial status in the country since the adoption of the Maple Leaf Flag in 1965.[11]

Calls for an official Empire flag

1897 imperial unity proposal

One of the first suggestions for a new flag representing the British Empire in its entirety was recorded to have been made in an 1897 Western Morning News article. An advisor to Queen Victoria from one of the colonies had reportedly suggested the creation of a common Empire flag to ensure everyone would feel as though they belong in the same polity, and this was expected to strengthen imperial unity. Their proposed design was a flag featuring the arms of the United Kingdom, the self-governing colonies, and India. Reactions were positive, but some felt unsure if it would truly unite the empire. The reason given was that many had fought and died under the Union Jack over the years, and it might have been difficult to accept a new flag.[12]

1901 English flag proposal

In 1901, William Laird Clowes wrote an article urging the creation of a common Imperial flag. He pointed out that the empire had over a dozen flags in use at the time, but there were cases where it would be desirable to avoid distinctions. It was argued that for occasions where the British Empire must be seen acting as a whole, it would be better to have a common flag representing all its subjects. While the Union Jack may have already filled this role, Laird Clowes believed it was too often supplanted by other flags depending on the situation. The Royal Navy had the White Ensign, the Naval Reserve used the Blue Ensign, and the mercantile marine used the Red Ensign. Each colony also had an ensign of its own. For an alternative, Laird Clowes suggested that the Cross of Saint George be promoted from being the flag of England alone to that of the entire British Empire. As it had been an English flag for a long period of history, it commanded significant respect.[13]

1901 imperial arms proposal

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

Also in 1901 was a proposal made by a Canadian writing to the St James's Gazette. Since Confederation, Canada had been using the quartered coats of arms of its founding provinces as a distinctive national badge for use on flags.[14] It was observed that the entry of Manitoba in the federation resulted in its arms being added to the badge by flag makers across the country. The article speculated that the Federation of Australia would result in a similar flag being designed using the arms of its states, and that an "uninterrupted evolution" of unique emblems from across the colonies would eventually form one Empire flag.[15]

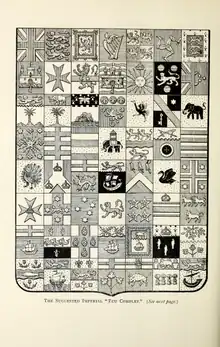

An unrelated but similar proposal was made to combine the coats of arms of all the colonies the year prior in 1900 by Edward Marion Chadwick, a prominent Canadian heraldist who was at the forefront of nurturing the study of armorial bearings in the country.[16] In response to a challenge put out by the Genealogical Magazine regarding colonial arms, he had conceived a shield of fifty-six quarterings in the style of the Canadian badge. Subdivisions of larger polities make up a large part of the total number. For example, the Canadian provinces are all featured separately rather than as one unit. Countries such as Wales were also afforded representation, despite usually being left out. Most arms were directly based on records made available by the British Admiralty, but some were allegedly so inadmissible for use that Chadwick took it upon himself to redesign them. Certain arms were entirely unique designs in cases where none existed, like those of the Northwest Territories.[17]

Compromises had to be made by Chadwick in many areas. The African arms featured are designed for entire regions, due to many of the colonies there having just been established. Furthermore, the Indian arms were a challenge due to the complex political divisions that existed on the subcontinent. Many princely states were left out, as Chadwick believed he could not represent their nobility with the grandeur necessary within a combined coat of arms. There was also the issue of representing differences in noble ranks. A maharajah ruling over a million subjects could not necessarily be placed on the same level as a rajah with a few thousand. The end result did not include as many of the territories of the British Empire as Chadwick would have liked, and he determined that it could not be officially adopted as a result. It is unknown if he continued developing these arms further, as he asks readers to submit suggestions for South African arms to be included in the future.[18] Nonetheless, the arms designed by Chadwick were well-aligned with the concept described in the St. James's Gazette, and could have formed the basis for the design of such an Empire flag.

1902 Daily Express proposal

.svg.png.webp)

In 1902, the Daily Express reported that the new King Edward VII was taking suggestions for an Empire flag. A man by the name of C. D. Bennett, identified only as "the cousin of a distinguished colonial governor," had come forward with a design. What he proposed was a Cross of Saint George to represent the English people, a similar rationale as Laird Clowes in 1901. A crown would be featured in the canton with a blue scroll underneath. The scroll would bear a Latin motto that could be translated as "the empire on which the sun never sets." A large sun would have defaced the centre of the flag to further reinforce that symbolism. The top right would be occupied by the unique emblem of the territory the flag would be flying in. For example, the Star of India would be used to represent the British Raj when flying the flag within its jurisdiction.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

Canadian and Australian variants with their own symbols were also mentioned in the article.[19] Australia did not have a coat of arms at the time. However, unofficial arms similar to those on the Bowman flag were observed throughout the country since before Federation.[20] It is unknown what the final verdict on this proposal was. However, public reactions to the proposed design may not have been very receptive. An Australian, in a letter to the editor featured in The Age, shared their concerns that the flag broke well-established rules of English heraldry by placing a yellow sun on a white background. Both colours are metals, and are typically forbidden from being placed next to each other.[21]

1905 British race proposal

A 1905 article in the Newcastle Morning Herald And Miners' Advocate promoted the Union Jack as the perfect symbol of the British race. The Union Jack was unique compared to the flags of Germany, France, and Russia, which all shared common design elements. Additionally, it was pointed out as not being subject to constant change like the American flag. The author described the Betsy Ross design adopted during the American Revolutionary War as being perfect, and the addition of stars for every new state as a sort of decay in purity. However, he still went on to advocate for the addition of five stars on the Union Jack to represent the dominions as integral units of the empire. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa would each have one. The fifth star would stand for "the other and less important possessions."[22]

Post-1910 flag proposals

There were high-level calls for an Empire flag in 1910, but discussions on this were deferred until the 1911 Imperial Conference.[23] It was ultimately not raised as a topic, with most of the discussion being focused on forming an Imperial Federation. The president of the Australian Natives' Association called for a "truly union flag of the empire" featuring the dominions in 1916. He felt it was necessary due to them taking up arms in defence of each other in the midst of the First World War.[24] This proposal was also backed by John Lavington Bonython, a former mayor of Adelaide. Lavington Bonython compared the emergence of the dominions to Scotland and Ireland uniting with England. What he called for was a small addition to the Union Jack, such as a thin cross that would not be too noticeable.[25] These proposals were rejected by association members, as they felt the Union Jack did well to represent the majority of the population with British heritage already.[26]

Reuters circulated a story in 1916 that the Daily Graphic had urged the adoption of an Imperial flag to take the role of the Union Jack. However, articles did not include details of what had been proposed.[27] Another call for an Empire flag was made by Prime Minister Massey of New Zealand near the end of the First World War in 1918. During a luncheon with Joseph Ward, Thomas Mackenzie, and other prominent New Zealander politicians, Massey lamented the losses that had been suffered by the dominions. He denounced the Germans for their role in sinking a Canadian hospital ship and a New Zealander steamship. After expressing a desire to continue fighting until Germany fell, Massey stated that the dominions deserved representation on a flag together with the United Kingdom as equal partners in the empire.[28]

It was reported in 1919 that the Empire Day Movement Committee in London had adopted a resolution urging the governments of the empire to discuss the creation of a new flag. The resolution was put forth by Godfrey Lagden, vice president of the Royal Colonial Institute, and seconded by Edward Lucas, the agent general for South Australia. The flag would be flown each Empire Day at churches and public buildings as a form of thanksgiving.[29] Prime Minister Lloyd George of the United Kingdom acknowledged the resolution in the House of Commons, but it is unknown if he took steps to adopt an Empire flag.[30] Later, there was speculation in 1921 that the partition of Ireland would result in a change to the Union Jack and an opportunity to add symbols of the dominions.[31] Ultimately, the Irish representation on the flag was kept, and no additions were made.

On the tenth anniversary of Anzac Day in Australia, the Federal Capital Pioneer reported that the headmaster of the Randwick Commercial Intermediate High School called for the creation of an official Empire flag during an address to students. It would have symbolized the combined effort undertaken by the empire to defeat Germany. The article reporting on this story supported creating what it had called a "Union Commonwealth Flag."[32] The "British Commonwealth of Nations" had already become a term with which to describe the dominions collectively by this time.

In 1926, efforts by South Africa to find a new national flag which may not have included the Union Jack as part of the design stirred controversy across the empire. The adoption of a wholly unique flag was viewed by some as a threat to imperial unity, and this spawned suggestions to indefinitely postpone the adoption of any new flags until a common Empire flag could be decided upon by all the dominions. A push was made to settle the matter in the next Imperial Conference.[33] No discussion was had, and South Africa adopted its new flag in 1928.

Proposals for an official Empire or Commonwealth flag continued to be made as late as 1953. Keith Cameron Wilson, a member of the Australian House of Representatives, used question time to ask Prime Minister Menzies if he would discuss adding dominion and colonial symbols to the Union Jack with his counterparts.[34] The Commonwealth of Nations would go on to adopt an organisational flag in 1976, but it carries no official status in any member state and has a vastly different intent than what an Empire flag was meant to be.

Oppostition to an Empire flag

Attempts at adopting an official Empire flag may not have been warmly received everywhere. The Australian tendency to create many local variations of British ensigns was acknowledged as a form of patriotism by Barlow Cumberland, a past president of the National Club, in his 1897 book detailing the history of the Union Jack in Canada. However, he also described it as a poor habit that promoted separatist ideas rather than promoting allegiance to the empire. Barlow believed that Canada had done much better in developing new and imperial ideas by utilizing more traditional flags, such as the Canadian Red Ensign.[35]

In 1902, after the Daily Express circulated reports on King Edward VII taking suggestions for an Empire flag, a column in the Montreal Daily Witness had a very negative reaction. The author declared that "there could not be a worse mistake in empire building than any interference with the flag." Following that were questions on whether the king actually granted someone a commission for a new flag, and a description of the design as preposterous. They were also sceptical that the colonies had even wanted to replace the Union Jack. According to the author, if the Union Jack represented the British, then it also served as a sufficient emblem for the rest of the empire since the colonies spawned descend from them. The author had concluded that it would be best to continue the practice of simply allowing each territory of the empire to fly ensigns defaced with their own symbols.[36]

Daniël François Malan, the South African minister at the forefront of the 1926 campaign to change the national flag, held the opinion that an Imperial flag was unnecessary. In his view, the British Empire had ceased to exist once the dominions were granted control of their foreign policy, and South Africa did not need to declare its neutrality if the British were to go to war anymore. A non-existent entity did not need a flag to represent itself. These sentiments were the subject of controvery among the British population of South Africa admist an already contentious flag debate.[37]

Unofficial Empire flag designs

.png.webp)

Despite the failure in gaining traction for an official Empire flag, an unofficial design with a strong similarity to the proposal originally described by the Daily Express in 1902 became popular among the public in the interwar period. This flag was a White Ensign featuring the symbols of the dominions. Canada was represented by the shield from its coat of arms in the bottom left. The coat of arms of South Africa was placed in the top right, and the coat of arms of Australia was in the bottom right. Four stars on the cross represented New Zealand, and the Star of India was placed in the centre. It is unknown how this flag came to be. This design could only have been adopted after 17 September 1910, when South Africa was granted its coat of arms. New Zealand did not adopt its coat of arms until 26 August 1911, and the absence of it on the flag provides a date before which the design was likely finalized. Most of these flags were sewn at proportions of 1:2 at full size or 2:3 for smaller hand-held formats, but examples of 3:5 and 5:8 designs also exist.[3]

Different variants of each coat of arms had been featured depending on the year in which each flag was manufactured. This can be seen in the arms of Canada changing after a new design was adopted in 1921. It is unknown why the Australian coat of arms originally used was never updated after being replaced in 1912,[38] but the 1908 design did receive a change in colours in later years that have not been observed elsewhere. There also appears to have been a 1921 variant of the Empire flag that was unique to Australia. It featured a wreath of maple and oak leaves around the Canadian coat of arms, a much smaller Star of India, and an off-centre Cross of Saint George. Additionally, the Canadian arms appear to be a design used from 1873 to 1907 due to the visible absence of Saskatchewan and Alberta. This variant of the flag was flown at the unveiling of the Dangarsleigh War Memorial in 1921.[3] Modern recreations of an Empire flag utilizing the arms of a post-1921 Canada and pre-1930 South Africa have been made,[39] but records of a design incorporating these elements together in the past do not appear to exist.

- Reconstructions of Empire flag variants

.svg.png.webp) 1910–1921: The original after a coat of arms was granted to South Africa

1910–1921: The original after a coat of arms was granted to South Africa.svg.png.webp) 1921: An Australian variant featuring a wreath around the arms of Canada

1921: An Australian variant featuring a wreath around the arms of Canada.svg.png.webp) 1921–1930: Canada adopts new arms to replace its quartering of provinces

1921–1930: Canada adopts new arms to replace its quartering of provinces.svg.png.webp) 1930–?: Updated arms for South Africa and erroneous colours for Australia

1930–?: Updated arms for South Africa and erroneous colours for Australia

The flag is most often believed to have been used for events such as Empire Day or the British Empire Exhibition as a patriotic display. A specimen is held in the Canadian Flag Collection,[40] and it is attributed to the 1924 edition of the latter.[41] However, it is unclear if the flag was designed specifically for these events. The British Empire Exhibition could have been the place of origin for the 1921 variant, since it occurred after Canada had adopted its new coat of arms, but that particular event aimed "to enable all who owe allegiance to the British flag to meet on common ground and learn to know each other." Introducing a new Empire flag runs counter to that statement, and most flags at the exhibition simply featured Union Jacks defaced by portraits of the monarch. Furthermore, the green compartment of the South African coat of arms often present on flags attributed to the British Empire Exhibition did not see formal adoption until 1930. Given the timing of updates made to the Empire flag, it is much more likely that most were distributed for coronations. The earliest date the Empire flag could have been designed is just before the coronation of King George V in 1911.[3]

Recorded uses of Empire flags

Despite its unclear origins, the Empire flag continued to show up in many locations. Many households, memorials, and schools throughout the British Empire could be found flying them. The flag was available in a variety of sizes and formats, and this indicates that numerous manufacturers produced them. An Empire flag catalogued in Victorian Collections is stated to have been made in England specifically.[42]

Victorian Collections also has an entry for an Empire flag from 1910 listed by the Lara branch of the Returned and Services League of Australia as a Commonwealth flag from the First World War.[43] However, there is no photographic evidence of the flag ever being used in battle. Another flag dated to 1910 can be found listed in Carter's Price Guides to Antiques and Collectables, and it is simply referred to as an Australian design rather than one for the empire as a whole.[44]

A 1919 photograph from Aldgate hosted by the State Library of South Australia demonstrates schoolchildren flying a number of British flags for a patriotic procession. The Empire flag can be seen among them.[45] The National Maritime Museum in London features a post-1930 Empire flag in a collection containing many other flags historically flown at sea. It is possible that it saw some use as a maritime flag, as the museum identifies it as a type of White Ensign.[46]

On Victory in Europe Day, the Daily Mirror published a photograph on its front page featuring the Empire flag. It is being flown by a woman in Trafalgar Square, celebrating the Allied victory with a large crowd.[47] After the liberation of Singapore from Japanese forces in 1945, prisoners of war who were kept at Changi Prison signed their names on an Empire flag. The prisoners were primarily Australian soldiers.[48] Due to the Empire flag appearing numerous times during the Second World War, it can be inferred that many copies were made during the 1930s. It is likely that the flag saw a revival before the beginning of any conflict to commemorate the coronation of King George VI in 1937.[3]

The Empire flag can still be found in use today at the Dangarsleigh War Memorial in New South Wales for special occasions. It was first opened on the Empire Day of 1921 with the flag hoisted above the monument. Below it was the flag of the United Kingdom (representing England) and the royal standards of Scotland and Ireland. On pillars around the monument were the ensigns of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and India. The Empire flag, referred to as a United Empire flag in some articles from the time, represented the eight countries on the memorial joined together.[49] A centennial celebration in 2021 saw an Empire flag flying over the memorial once more. It featured older designs for the coats of arms to match the one used at the original unveiling. This is one of the few places in the world where the Empire flag was recorded to have been flown in some official capacity, and the monument even appears to have been designed with its use in mind.[50]

References

- ↑ "History of the National Flag of Canada". canada.ca. Department of Canadian Heritage. 4 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ Prothero, David. "Flags of the British Empire and Commonwealth". Historical Flags of Our Ancestors. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kelly, Ralph (8 August 2017). "A flag for the Empire" (PDF). The Flag Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ↑ "The Empire and Unity". Northern Advocate. 23 January 1914. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of New Zealand.

- ↑ "Flags and Anthems, Their Uses and Abuses, Australian Misconceptions". Freeman's Journal. Vol. LXXIV. New South Wales, Australia. 22 May 1924. p. 27. Retrieved 3 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Not Empire Flag, The Union Jack". Wairarapa Daily Times. 8 September 1926. p. 5. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of New Zealand.

- ↑ Crampton, William (1990). "Flags Without End". The World of Flags. London: Studio Editions. p. 155. ISBN 9781851704262. OL 17364072M. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "The Empire Flag and the Dominions". Southern Cross. Vol. XXXVII, no. 1905. South Australia. 4 June 1926. p. 5. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ E. Flood, Cyril (22 June 1926). "Other People's Views, Our Flag". The Southern Mail. Vol. 39, no. 50. New South Wales, Australia. p. 2. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Flag Item Rouses Anger of Senator". Sherbrooke Daily Record. 6 November 1946. p. 1. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Foreign flags in Canada". canada.ca. Department of Canadian Heritage. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ↑ "A Good Suggestion". Evening Express. No. 3, 135. Cardiff: Walter Alfred Pearce. Western Morning News. 1 July 1897. p. 3. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of Wales.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "An Imperial Flag". The Mercury. Vol. LXXV, no. 9626. Tasmania, Australia. 16 January 1901. p. 3. Retrieved 3 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Arms & Badges - Royal Arms of Canada, A Brief History". Royal Heraldry Society of Canada. Archived from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ↑ "An Empire Flag". Otago Daily Times. No. 11944. 18 January 1901. p. 3. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of New Zealand.

- ↑ C. Ian, Kyer. "Edward Marion Chadwick". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ↑ Vachon, Auguste. "Arms and Devices of Provinces and Territories". Heraldic Science Héraldique. Northwest Territories. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ↑ Chadwick, Edward Marion (1900). "The Imperial "Ecu Complet"". The Genealogical Magazine. Vol. 3. London: Elliot Stock. p. 378. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "A British Empire Flag". The New York Times. The London Express. 9 February 1902. p. 3. Retrieved 20 August 2023 – via The New York Times Archives.

- ↑ "The Bowman flag". State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ Wilson Dobbs, E. (22 February 1902). "An Imperial Flag, To the Editor of The Age". The Age. No. 14653. Victoria, Australia. p. 4. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "The Imperial Flag of the Race". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate. No. 9500. New South Wales, Australia. 20 May 1905. p. 5. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Empire Flag, Subject Will Probably Be Settled at Imperial Conference" (PDF). The Winnipeg Tribune. Vol. 21, no. 242. 7 November 1910. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ↑ "Imperial Flag, Will Tighten Bonds of Empire, Says A.N.A. President". The Mail (Adelaide). Vol. 3, no. 207. South Australia. 29 April 1916. p. 10. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Imperial Flag, Recognition of Dominions, Mr. Lavington Bonython's Splendid Proposal". The Mail (Adelaide). Vol. 3, no. 206. South Australia. 22 April 1916. p. 1. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "The Flag". The Register (Adelaide). Vol. LXXXI, no. 21686. South Australia. 11 May 1916. p. 4. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "New Imperial Flag". The Ballarat Courier. Vol. CIII. Victoria, Australia. Reuters. 13 July 1916. p. 3. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Murderers and Fiends, An Account to Settle, The Empire Flag". The Express And Telegraph. Vol. LV, no. 16478. South Australia. 11 July 1918. p. 1. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Proposed Imperial Flag". Adelaide Chronicle. Vol. LXII, no. 3202. South Australia. 3 January 1920. p. 34. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Empire Day, New Significance, Imperial Flag Proposed, Symbols of the Dominions". The New Zealand Herald. Vol. LVII, no. 17402. 24 February 1920. p. 5. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of New Zealand.

- ↑ "The Union Jack, Will It Be Changed? Effect of Ireland's New Status, Chance to Design an Empire Flag". The Daily News. Vol. XLI, no. 14620. Western Australia. 20 January 1922. p. 6. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "War Anniversary, Empire Flag Suggested". Federal Capital Pioneer. No. 8. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 20 August 1925. p. 3. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "An Empire Flag, South Africa's Position, Australian Hint". Toowoomba Chronicle And Darling Downs Gazette. Vol. LXVI, no. 93. Queensland, Australia. 21 April 1927. p. 10. Retrieved 1 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "House of Representatives, Official Hansard" (PDF). Parliament of Australia. 6 October 1953. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ↑ Cumberland, Barlow (1897). "Union Flag of the British Empire". The Story of the Union Jack. Toronto: William Briggs. pp. 220–221. OL 23342493M. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Dougall, John, ed. (17 February 1902). "The Daily Witness". Daily Witness. Vol. XLIII, no. 40. Montreal. p. 4. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Imperial Flag Unnecessary, As There Is No Empire". The Albany Despatch. Vol. 9, no. 863. Western Australia. 3 November 1927. p. 2. Retrieved 2 December 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ "Commonwealth Coat of Arms". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. 22 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ "A historic flag by Artelina Sewn Flags". Artelina Sewn Flags. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ↑ "Canadian Flag Collection". Settlers, Rails & Trails. Royal Union Flags. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ Stevenson, Lorraine (23 May 2018). "Argyle museum waves the flag – all 1,300 of them". The Manitoba Co-operator. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ↑ "Flag - British Empire Exhibition Flag - Wembley 1924-25, British Empire Exhibition Flag - Wembley 1924 -1925, 1924 or 1925". Victorian Collections. Archived from the original on 26 November 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ↑ "British Commonwealth of Nations flag circ world war 1, British Commonwealth of Nations flag world war 1". Victorian Collections. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ↑ "Oak-framed Australian flag with Southern Cross and Union Jack". Carter's Price Guides to Antiques and Collectables. Archived from the original on 1 December 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ↑ "Schoolchildren with flags at a patriotic procession [PRG 280/1/24/128] • Photograph". State Library of South Australia. 1 January 2002. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ↑ McKenzie, Sheena (25 April 2016). "Flying the flag: Decoding sailing's secret symbols". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ↑ Willis, Peter (1 May 2015). "VE Day: Full edition of Daily Mirror from day of Britain's greatest triumph FREE with today's paper". The Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ↑ Xinfeng, Zhao (11 March 2022). "EXCURSION to CANBERRA - Wednesday 2 September 2015" (PDF). Flag Society of Australia. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ↑ "At Dangarsleigh, Memorial Unveiled". The Armidale Chronicle. 25 May 1921. p. 8. Retrieved 30 September 2023 – via National Library of Australia.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Ingall, Jennifer (4 June 2021). "Why the Dangarsleigh war memorial flies the Empire flag and what it means to the community". ABC News. Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 13 August 2023.