| Battle of Guaxenduba | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

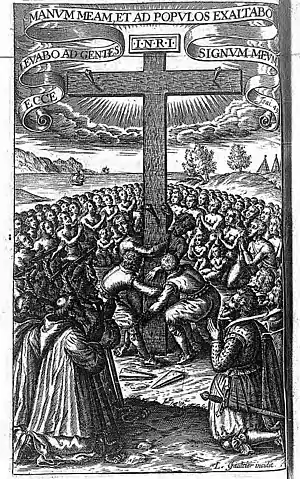

Raising a cross for the blessing of the island of Maranhão - Founding of Equinoctial France | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Around 240 Portuguese 30 sailors less than 100 natives |

200 French soldiers 2,500 natives 50 canoes | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

10 soldiers killed 18 wounded |

115 soldiers killed 8 soldiers captured 46 canoes burned 200 firearms captured | ||||||

The Battle of Guaxenduba (Portuguese: Batalha de Guaxenduba) was a military confrontation that took place on November 19, 1624, near where the city of Icatu is located today, in the state of Maranhão, Brazil. It involved the Portuguese forces, under the command of the Mamluk Jerônimo de Albuquerque, and the French army, led by Daniel de La Touche, lord of La Ravardière.[1]

Background

In 1555, the French tried to establish a colony in Rio de Janeiro, which became known as France Antarctique, but it was extinguished in 1560. In 1612, in Maranhão, with the support of the local natives, the French again tried to establish a colony in Portuguese territory; on September 8, the settlement of Saint Louis was founded and, on a hill overlooking the sea where the Palace of the Lions now stands, construction of the Fort of São Luís do Maranhão began.[2][1]

Aware of the French presence to the north of the Captaincy of Maranhão, Gaspar de Souza sent troops from Pernambuco. On August 23, 1614, Diogo de Campos left Recife with 300 men and, in Rio Grande do Norte, joined Jerônimo de Albuquerque, who was taking a large contingent of natives with him. The Portuguese expedition with 500 men led by captain-major Jerônimo camped on the bar of the Perejá River in order to find a place to build a fortification, but faced a shortage of food and quality water. A group of 14 Portuguese explorers discovered a suitable place to build a fort, and the expedition set sail again on October 2, 1614. On October 26, they reached an area that the indigenous people called Guaxindubá, located on the right bank of São José Bay, between many islands and narrow channels. Under the guidance of engineer Francisco Frias de Mesquita, a hexagonal fortification called Fort of Santa Maria was built on the beach of Guaxenduba, about 20 km from the current seat of the municipality of Icatu. At the same time, the French settled in the Fort of São José de Itapari, in São José de Ribamar.[2]

Once established, the Portuguese began to work on the construction and surveillance of the fort and the reconnaissance of the region. When the natives made contact with the Portuguese, some of them said that it was full of French people, while others said that they had left.[2]

On October 30, a group of natives killed four indigenous women and an indigenous man who were accompanying the Portuguese, leading them to distrust the locals and believe that they had been sent by the French to reconnoiter their ships. Towards the end of October, the Portuguese in the Fort of Santa Maria and on the island of Santana noticed the movement of French ships in the São José Bay and the landing of artillery.[2][3]

First French attack

On November 10, 1614, the sergeant-major Diogo de Campos, after a disagreement with Jerônimo de Albuquerque, sent a group of sailors to defend the ships that were anchored or stranded in the estuary, requesting that they remain vigilant. In the early hours of November 11, the French, led by Monsieur de Pézieux, Monsieur du Prat and François Rasilly, approached the ships silently. When they noticed the attack, the sailors blew their trumpets and alerted the soldiers in the fort, who fired their artillery relentlessly, but it had no effect on the French. The sailors abandoned and left the vessels free; a caravel, a war boat and a ship that were further from land were captured by the French.[4][3]

The battle

Beginning of the conflict

On the morning of November 19, 1614, the Portuguese soldiers noticed that the sea was full of sailing and rowing vessels approaching the coast next to the Fort of Santa Maria. In order to attack them in the landing, Diogo de Campos headed for the beach with 80 Portuguese soldiers, but, realizing that the number of enemies was much greater, he retreated. Soon, there were hundreds of soldiers on the beach. The French had 200 soldiers, many of whom were noblemen, in two troops, carrying steel vests, swords and high-quality muskets. They had 50 canoes and 2,500 natives, including 2,000 indigenous people from Tapuitapera (now Alcântara) and 100 from Cumã (now Guimarães). Daniel de La Touche, commander of the French, was at sea with another 200 men led by the knight François Rasilly. A long exchange of fire began; in this first encounter, a Portuguese soldier and two Frenchmen were killed.[4][3]

Trenches

In front of the fort of Santa Maria there was a hill bordered to the north by the sea and to the south by the river; the French landed by sea. Under the command of Monsieur de La Fos-Benart, around 400 Tupinambá people on the French side were ordered to fortify the peak as much as they could: they built a total of seven trenches with large stones, strengthening the entire space between the tide and the top of the hill, ensuring that the incoming canoes were partially hidden. By a secret route, Jerônimo de Albuquerque climbed the hill with 75 soldiers and 80 archers, while Diogo de Campos attacked the French and natives who were landing. On shore, he jumped out of a canoe with a trumpet bearing the royal coat of arms of France and a letter written by Daniel de La Touche, which said that the Portuguese should surrender in 4 hours or be massacred. Diogo de Campos realized that the document was an attempt by the French to gain time and obtain information about the condition of the Portuguese troops.[4][3]

By now, the group of soldiers and archers accompanying Jerônimo de Albuquerque had reached the first trench. The natives who defended it with the French were a large crowd, but the Portuguese never missed a shot. Daniel de La Touche watched from the sea as the French army suffered heavy casualties; in less than an hour, the area around the Fort of Santa Maria was littered with French and indigenous dead. He sent the fastest ships close to the beach to prevent further damage to his troops, but under the bombardment of Portuguese artillery, he was forced to give up. Once the Portuguese had taken control of the fortified hill, Diogo de Campos ordered them to set fire to all the canoes that were at the base of the slope.[4][3]

French withdrawal

With all the canoes in flames, the remaining Frenchmen on land had no way of escaping and all they could do was retreat to the fortification at the top of the hill. Among them were Monsieur de la Fos Benart and Monsieur de Canonville. At the end of the battle, near the hill, many of the Portuguese soldiers stood in front of the muskets of the enemies, who were still resisting. Turco, who was the French interpreter for communication with the natives, was shot by the Portuguese, and with him, Monsieur de la Fos Benart, the leader of the indigenous people who were fighting with the French. Without guidance, the remaining 600 natives began to retreat down the hill and were joined by the French soldiers, who no longer had any gunpowder to fire.[4][3]

Truce and expulsion of the French

After the Battle of Guaxenduba, the remaining French troops in Maranhão were trapped in Fort of São Luís. To buy time, Daniel proposed a truce to the Portuguese, which was accepted, stipulating that a Portuguese and a French officer should go to France and Portugal to seek a solution to the conflict at the courts of those countries.[5]

With the ceasefire announced, the Portuguese, French and natives remained at peace. In October 1615, the captain-major of Pernambuco, Alexandre de Moura, arrived in Maranhão with more troops and supplies. As he was of higher rank, he took overall command of the Portuguese troops. Under his command, the Portuguese violated the treaty made with the French and ordered Daniel de La Touche to leave Maranhão within five months with a commitment to compensate him. As a safeguard of his promise, he handed over the Fort of Itapari. Three months later, Diogo de Campos and Martim Soares arrived from Europe, bringing more Portuguese troops and final orders from the court for the French to abandon Brazil once and for all. On November 1, 1615, Alexandre de Moura landed his troops at the tip of São Francisco and ordered the Fort of São Luís to be surrounded.[5][4]

The fort was attacked and, after two days of fighting, Daniel de La Touche surrendered. Instead of compensating the French, as had been agreed, the Portuguese sent them back to France in two ships carrying only what they needed. Some Frenchmen remained in Maranhão, such as Charles Des Vaux, who helped communicate with the natives; the others were mostly blacksmiths. In January 1616, Daniel de La Touche was forcibly taken to Pernambuco, where he received compensation and a pardon from the governor-general to prevent him from joining other French privateers and leading them again. In 1619, when he demanded an increase in the pension stipulated by the Portuguese Crown, he was arrested in Lisbon and imprisoned for three years in the Tower of Belém.[5][4]

Legend of the Guaxenduba miracle

In the 1759 book "História da Companhia de Jesus na Extinta Província do Maranhão e Pará", Father José de Moraes recounts the apparition of Our Lady of Victory among the Portuguese battalions, encouraging the soldiers throughout the conflict and turning sand into gunpowder and stones into projectiles. Our Lady of Victory is considered the patron saint of São Luís; the city's cathedral, which is also named after her, has the following scripture in Latin: 1629 - SANCTÆ MARIÆ DE VICTORIA DICATUM - 1922.[6]

Use of telescopes

The Battle of Guaxenduba would have been one of the first combat situations in which the use of a telescope was reported. Diogo de Campos reports:[7]

At this time, with some arquebusiers, the sergeant-major began to stop the skirmish to see how they were getting on, and when two Frenchmen and a soldier of the Portuguese had fallen, the work stopped, and the sergeant-major came to the fort to see what his colleague was ordering, whom he found with a long-sighted spyglass looking through a bombardier at what the enemies were doing [...].[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 Cunha, Patricia (2019-11-17). "405 anos de uma batalha épica". O Imparcial. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- 1 2 3 4 "A Batalha de Guaxenduba – O fim de um sonho". Jornal DR1. 2022-02-06. Retrieved 2023-11-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Moreno (2011)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Melo, Maria de Nazaré; Santos, Maysa; Silva, Naysa Christine. "A Batalha de Guaxenduba no Maranhão" (PDF). International Journal of Current Research. 13 (11): 19481–19488. doi:10.24941/ijcr.42423.11.2021. ISSN 0975-833X.

- 1 2 3 Mascarenhas (1898)

- ↑ Moraes, José de (1860). Historia da Companhia de Jesus na extincta provincia do Maranhão e Pará. Typographia do Commercio de Brito & Braga.

- ↑ "Os primeiros telescópios em Portugal". CVC. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

Bibliography

- Moreno, Diogo de Campos (2011). Jornada do Maranhão por ordem de Sua Majestade feita o ano de 1614 (PDF). CEDIT.

- Mascarenhas, Anibal (1898). Curso de Historia do Brasil. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1293494981.

- Lopez, Adriana; Mota, Carlos Guilherme (2008). História do Brasil: uma interpretação. São Paulo: Senac. ISBN 978-85-7359-789-9.

- Lacroix, Maria de Lourdes Lauande (2006). Jerônimo de Albuquerque Maranhão: guerra e fundação no Brasil colonial. UEMA.