| Battle of Big Black River Bridge | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

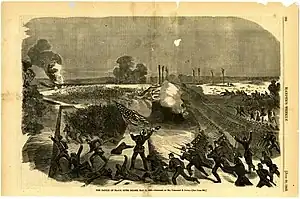

The Battle of Big Black River Bridge, Harper's Weekly, June 20, 1863 issue | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| United States | Confederate States | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John McClernand |

John Bowen John Vaughn | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| XIII Army Corps |

Bowen's Division Vaughn's Brigade | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,500[2] | 5,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 276 | 1,751 | ||||||

Location within Mississippi | |||||||

The Battle of Big Black River Bridge was fought on May 17, 1863, as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. After a Union army commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant defeated Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton's Confederate army at the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16, Pemberton ordered Brigadier General John S. Bowen to hold a rear guard at the crossing of the Big Black River to buy time for the Confederate army to regroup. Union troops commanded by Major General John McClernand pursued the Confederates, and encountered Bowen's rear guard. A Union charge quickly broke the Confederate position, and during the retreat and river crossing, a rout ensued.

Many Confederate soldiers were captured, and 18 Confederate cannons were taken by the Union troops. The retreating Confederates burned both the railroad bridge over the Big Black River and a steamboat that had been serving as a bridge. The surviving Confederate soldiers entered the fortifications at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the siege of Vicksburg began the next day.

Background

Early in the American Civil War, the Union military leadership developed the Anaconda Plan, which was a strategy to defeat the Confederate States of America. A significant component of this strategy was controlling the Mississippi River.[3] Much of the Mississippi Valley fell under Union control in early 1862 after the capture of New Orleans, Louisiana, and several land victories.[4] The strategically important city of Vicksburg, Mississippi was still in Confederate hands, serving as a strong defensive position that commanded the river and prvented the Union from separating the two halves of the Confederacy.[5] Union Navy elements were sent upriver from New Orleans in May to try to take the city, a move that was unsuccessful.[6] In late June, a joint army-navy expedition returned to make another campaign against Vicksburg.[7] Union Navy leadership decided that the city could not be taken without more infantrymen, who were not forthcoming. An attempt to cut Williams's Canal across a meander of the river in June and July, bypassing Vicksburg, failed.[8][9]

In late November, about 40,000 Union infantry commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant began moving south towards Vicksburg from a starting point in Tennessee. Grant ordered a retreat after a supply depot and part of his supply line were destroyed during the Holly Springs Raid on December 20 and Forrest's West Tennessee Raid. Meanwhile, another arm of the expedition under the command of Major General William T. Sherman left Memphis, Tennessee, on the same day as the Holly Springs Raid and traveled down the Mississippi River. After diverting up the Yazoo River, Sherman's men began skirmishing with Confederate soldiers defending a line of hills above the Chickasaw Bayou. A Union attack on December 29, was defeated decisively at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, and Sherman's men withdrew on January 1, 1863.[10]

By late March, further attempts to bypass Vicksburg had failed.[11] Grant then considered three plans: to withdraw to Memphis and retry the overland route through northern Mississippi; to move south along the west side of the Mississippi River, cross below Vicksburg, and then strike for the city; or to make an amphibious assault across the river directly against Vicksburg. An assault across the river risked heavy casualties, and a withdrawal to Memphis could be politically disastrous if the public perceived such a movement as a retreat. Grant then decided upon the downstream crossing.[12] The advance along the west bank of the Mississippi began on March 29, and was spearheaded by Major General John A. McClernand's troops, the XIII Corps.[13] The movement down the river was masked by decoy operations such as Steele's Greenville expedition,[14] Streight's Raid, and Grierson's Raid.[15] Confederate regional commander John C. Pemberton fell for the Union decoys (especially Grierson's Raid), and lost touch with the true tactical situation, believing Grant was withdrawing.[16]

Prelude

On April 29, the Union Navy's Mississippi Squadron commanded by David Dixon Porter attempted to bombard the Confederate defenses at Grand Gulf, Mississippi, but the resulting Battle of Grand Gulf failed to drive the Confederates away. With Grand Gulf still in enemy hands, Grant decided to cross further downriver.[17] Beginning on the morning of April 30, the lead elements of Grant's army, McClernand's corps, crossed the river at Bruinsburg, Mississippi.[18] Brigadier General John S. Bowen, the Confederate commander at Grand Gulf, would be flanked out of the position there if Grant crossed Bayou Pierre. Bowen moved a portion of his force to Port Gibson to block the Union movements,[19] but he did not have enough troops to destroy Grant's bridgehead and had to hold out for further reinforcements.[20] The two armies collided on May 1, and the Battle of Port Gibson began.[21] After a day of fighting, the Confederates were defeated, and Grand Gulf was abandoned on May 3.[22]

After Port Gibson, Grant moved his troops to the northeast.[23] McClernand advanced on the Union left with his corps, Sherman and the XV Corps in the center, and Major General James B. McPherson and the XVII Corps on the right.[24] On the morning of May 12, McPherson's encountered Confederate troops near Raymond, Mississippi, bringing on the Battle of Raymond.[25] The Union won the battle, but the fighting at Raymond led Grant to change his plans to swing over towards Jackson, Mississippi, to disperse a Confederate force gathering there.[26] The Confederate commander at Jackson, General Joseph E. Johnston, decided to abandon Jackson. A delaying action was fought on May 14,[27] with the Union taking the city and then destroying military facilities within it.[28]

After he had already withdrawn from Jackson, Johnston sent Pemberton orders to move east, stating that Johnston's army would move west and catch Grant's commend between the two Confederate forces. However, Johnston then marched his army away from the area in which a combination with Pemberton could easily be made.[29] Pemberton decided that Johnston's orders were not compatible with previous directives that Pemberton had received from the Confederate president. While Pemberton favored making a stand behind the Big Black River, he was convinced by some of his subordinate officers to make an offensive strike towards where Grant's supply line was believed to be.[30] Pemberton did not know that Grant had forgone utilizing a traditional line of communications during his movement inland.[31] While Pemberton began a difficult march, Grant moved west in three columns towards Edwards.[32] On the morning of May 16, elements of the Union and Confederate armies made contact, and Pemberton ordered his force to march back to Edwards.[33] The ensuing Battle of Champion Hill was a decisive Confederate defeat.[34] Major General William W. Loring's Confederate division was cut off during the retreat from the field and withdrew using a different route, separated from the rest of Pemberton's army.[35] Pemberton did not know the location of Loring's division.[36]

Battle

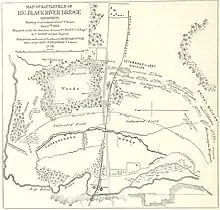

.jpg.webp)

On the night of the 16th, after the defeat at Champion Hill, Pemberton formed a line at the crossing of the Big Black River in order to buy time for his army. For this rear guard, Pemberton selected the Missouri troops of Bowen's division, Brigadier General John C. Vaughn's Tennessee brigade, and the 4th Mississippi Infantry Regiment.[37] This force numbered about 5,000 men.[38][39] The left of the Confederate line was held by Brigadier General Martin E. Green's brigade of Bowen's division, Vaughn's brigade held the center, Bowen's other brigade, commanded by Colonel Francis M. Cockrell, was positioned on the Confederate right, and the 4th Mississippi was placed between Cockrell and Vaughn. Vaughn's brigade was composed of inexperienced conscripts, and Bowen's division had seen heavy fighting at Champion Hill. The Confederate line was supported by Wade's Missouri Battery, Landis' Missouri Battery, and Guibor's Missouri Battery.[37] A railroad ran through the Confederate position, and the river could be crossed either over the railroad bridge or over a steamboat that had been positioned crossways across the river, creating a makeshift bridge.[40]

On the morning of May 17, McClernand's XIII Corps advanced towards the Confederate position at the Big Black River.[2] Brigadier General Eugene A. Carr's division led the way, and deployed to confront the Confederate lines. The brigade of Brigadier General Michael K. Lawler formed the right of the Union line. Carr was soon reinforced by Brigadier General Peter J. Osterhaus' division. An artillery duel began, and Osterhaus was wounded in the leg by a shell fragment. After some preparations, Lawler's brigade charged, quickly breaking the Confederate line. Vaughn's brigade routed to the rear, and the gap in the line quickly forced Green's brigade to retreat as well.[41] Lawler's charge had lasted only three minutes.[38] Cockrell's brigade also collapsed in much disorder, one survivor summarized the retreat as "the devil take the hindmost being the order of the day."[42] The 1st and 4th Missouri Infantry Regiment (Consolidated) served as a rear guard for the retreating Confederates, as it was one of the few units still in functioning order.[43] The Confederates lost a number of cannons in the retreat due to an error; the horses for Wade's Battery, Guibor's Battery, and a portion of Landis's Battery had been positioned on the far side of the Big Black River, and were not available to haul off the cannons.[42] In total, the Confederates lost 18 cannons at the Big Black River. The retreating Confederates burned both the bridge and the steamboat serving as a bridge, and those who escaped the Union army joined the fortifications at Vicksburg.[38]

Sergeant William Wesley Kendall of the 49th Indiana Infantry Regiment was awarded the Medal of Honor for leading a company in the main Union charge; he was among the first Union soldiers to enter the Confederate fortifications.[44]

Aftermath and preservation

The Confederates lost 1,751 men; almost 1,700 of the losses were in prisoners. Union casualties totaled either 273[2] or 276.[38] After Big Black River Bridge, the siege of Vicksburg began on May 18. Grant attempted a major charge against the Vicksburg entrenchments on May 22, but this was repulsed. Attempts at exploding mines under the Confederate lines on June 25 and July 1 also failed to break the Confederate defenses. However, with no prospects of reinforcements and lack of food, Pemberton surrendered the Confederate defenders on July 4.[45]

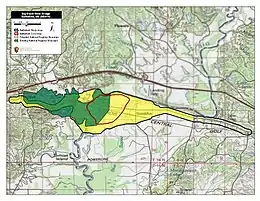

The site of the battle was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971 as the Big Black River Battlefield.[46] As of 2020, portions of the piers of the railroad bridge existing during the battle still remain at the crossing of the Big Black River. A trail runs along the river bank, and a historical marker is placed in the vicinity of the battlefield, although the battlefield itself is privately owned. As of mid-2023, the American Battlefield Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved 28 acres (11 ha) of the battlefield.[47]

References

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, p. 170.

- 1 2 3 "Battle of Big Black River Bridge". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, p. 203.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 15–16, 18–20.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 135–138.

- ↑ Miller 2019, p. 153.

- ↑ "Grant's Canal". National Park Service. October 25, 2018. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ↑ Winschel 1998, pp. 154, 156.

- ↑ Bearss 1991, pp. 19–22.

- ↑ Bearss 1991, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Ballard 2004, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Bearss 1991, p. 126.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 96, 103–104.

- ↑ Ballard 2004, p. 221.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 41.

- ↑ Ballard 2004, pp. 224–225.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 116.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, p. 220.

- ↑ Ballard 2004, pp. 274–275.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 126.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, p. 222.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 129.

- ↑ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, p. 230.

- ↑ Smith 2006, pp. 356–361.

- ↑ Bearss 2007, p. 231.

- 1 2 Tucker 1993, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 4 Kennedy 1998, p. 171.

- ↑ Ballard 2004, p. 310.

- ↑ Ballard 2004, pp. 310–311.

- ↑ Ballard 2004, pp. 313–316.

- 1 2 Tucker 1993, p. 180.

- ↑ Tucker 1993, pp. 180–182.

- ↑ "49th Indiana's own Medal of Honor Recipient". Ohio State University. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, pp. 171–173.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form". National Park Service. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ↑ "Big Black River Bridge Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

Sources

- Ballard, Michael B. (2004). Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1991) [1986]. The Campaign for Vicksburg. Vol. II: Grant Strikes a Fatal Blow. Dayton, Ohio: Morningside Bookshop. ISBN 0-89029-313-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (2007) [2006]. Fields of Honor. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0093-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Shea, William L.; Winschel, Terrence J. (2003). Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9344-1.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2006) [2004]. Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie. ISBN 1-932714-19-7.

- Tucker, Phillip Thomas (1993). The South's Finest: The First Missouri Confederate Brigade from Pea Ridge to Vicksburg. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Publishing Co. ISBN 0-942597-31-1.

- Winschel, Terrence J. (1998). "Chickasaw Bayou, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston, Massachusetts/New York, New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

Further reading

- Fullenkamp, Leonard, Stephen Bowman, and Jay Luvaas. Guide to the Vicksburg Campaign. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998. ISBN 0-7006-0922-9.

- Winschel, Terrence J. Triumph & Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing Company, 1999. ISBN 1-882810-31-7.

- Woodworth, Steven E., ed. Grant's Lieutenants: From Cairo to Vicksburg. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001. ISBN 0-7006-1127-4.