| Alpine ibex | |

|---|---|

_Zoo_Salzburg_2014_h.jpg.webp) | |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Caprinae |

| Tribe: | Caprini |

| Genus: | Capra |

| Species: | C. ibex |

| Binomial name | |

| Capra ibex | |

| |

| Range map in the Alps | |

The Alpine ibex (Capra ibex), also known as the steinbock, is a species of goat antelope that lives in the mountains of the European Alps. Its is one of seven species in the wild goat genus Carpa and its closet living relative is the Iberian ibex. The Alpine ibex is a sexually dimorphic species: males are larger and carry longer horns than females. Its coat colour is typically brownish grey. Alpine ibex tend to live in steep, rough terrain and open alpine meadows. Their sharp hooves allow them to scale nearly vertical surfaces.

Alpine ibex primarly feed on grass and are active throughout the year. They are also social, although adult males and females segregate for most of the year, coming together only to mate. During the breeding season, males fight for access to females, and use their long horns in agonistic behaviour. Ibex have few predators but do succumb to various parasites and diseases.

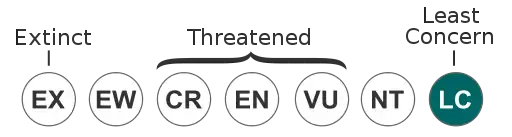

After being extirpated from most areas by the 19th century, the Alpine ibex was successfully reintroduced to parts of its historical range. All individuals living today descend from the stock in Gran Paradiso National Park in Italy. The species is currently listed as of least concern by the IUCN, but went through a population bottleneck of fewer than 100 individuals during its near-extinction event. This has led to very low genetic diversity across populations.

Naming

The Alpine ibex has also been called the steinbock, a combination of the Latin stein ("rock") and the Germanic bock or bod ("male goat"). Several European names for the animal developed from this, including the French bouquetin, and Italian stambecco.[2]

Taxonomy

The Alpine ibex was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. It is classified in the genus Capra (Latin for "goat") with at least seven other species of wild goats. Fossils of the genus Tossunnoria are found in late Miocene deposits in China and appears to have been a transitional fossil between goats and their ancestors.[3] The genus Capra may have originated in Central Asia and colonized Europe, the Caucasus, and East Africa from the Pliocene and into the Pleistocene. Mitochondrial and Y chromosome evidence show hybridisation of species in this lineage.[4]

Fossils of Alpine ibex date back to the late Pleistocene (during in the last glacial period), along with the Iberian ibex, and it probably evolved from the extinct Pleistocene species Capra camburgensis.[3] The Nubian (C. nubiana), walia (C. walie), and Siberian ibexes (C. sibirica) were considered to be subspecies of the Alpine ibex in the 20th century, giving populations in the Alps the trinomial of C. i. ibex.[5] Subsequent genetic evidence has supported them as separate species.[4]

The following cladogram is based on mitochondrial evidence:[6]

| Capra |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Appearance

Alpine ibex are sexually dimorphic.[7] Males commonly grow to a height of 90 to 101 cm (35 to 40 in) at the withers, with a body length of 149 to 171 cm (59 to 67 in) and weigh from 67 to 117 kg (148 to 258 lb). Females have shoulder height of 73 to 84 cm (29 to 33 in), a body length of 121 to 141 cm (48 to 56 in), and a weight of 17 to 32 kg (37 to 71 lb).[3]

The Alpine ibex is a stocky animal, with a tough neck and robust legs with short metapodials. Compared with most other wild goats, the species has a wide, and shortened snout. Adaptations for climbing include sharp, highly separated hooves and a rubbery callus on the front feet.[7][3] Both male and female Alpine ibex have large, backwards-curving horns with numerous transverse ridges along their length. At 69 to 98 cm (27 to 39 in), those of the males are substantially larger than those of females, which reach only 18 to 35 cm (7.1 to 13.8 in) in length.[3]

The species has brownish-grey hair over most of the body, lighter on the belly, with darker markings on the chin and throat. The hair on the chest region is nearly black while stripes exist along the dorsal (back) surface. It is duller coloured than other members of its genus. A beard exists only in males. Ibex moult in spring, when their thick winter coat, consisting of woolly underfur, is replaced with a short, thin summer coat. Their winter coat grows back again starting in the fall.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The alpine ibex is native to the Alps mountains, its range including France, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Italy, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.[8] Fossils of the species have been found as far south as Greece, where they appear to have gone extinct due to hunting over 7,500 years ago.[9] Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the species disappeared from much of its range due to hunting, leaving only one population surviving in and around Gran Paradiso National Park by the 19th century. They have since been reintroduced into parts of its former range.[8]

An excellent climber, it occupies steep, rough terrain at elevations of 1,800 to 3,300 m (5,900 to 10,800 ft). Alpine ibex prefer to live an open areas,[3] but when there is little snow, adult males may gather in larch and mixed larch-spruce woodland depending on population density.[10] Outside the breeding season, the sexes live in separate habitats.[10][11] Females are more likely to be found on steep slopes while males prefer more level ground. Males inhabit lowland meadows during the spring, when fresh grass appears.[3] They then climb to alpine meadows during the summer.[10] Both males and females move to steep, rocky slopes when winter arrives, to avoid dense buildups of snow.[12] They prefer slopes of 30–45° and take refuge in small caves and overhangs.[13]

Behaviour and ecology

Alpine ibex are strictly herbivorous, with over half of their diet consisting of grasses, and the remainder being a mixture of mosses, flowers, leaves, and twigs. Grass genera that are the most commonly eaten are Agrostis, Avena, Calamagrostis, Festuca, Phleum, Poa, Sesleria, and Trisetum.[3] The length of daytime foraging is similar between the sexes during the spring, while in summer, females feed more than males to maintain lactation.[14] Hotter temperatures also give large adult males heat stress, thus reducing their feeding time.[15]

Home range sizes depend on the availability of resources and the time of year. Home ranges tend to be largest during summer and autumn, smallest in winter, and intermediate in spring. Female home ranges are usually smaller than those of males. In reintroduced, populations, individuals wander more widely.[3][12][16] Ibex do not hibernate during the winter; they take shelter on cold winter nights and bask in the morning. In addition, they also reduce their heart rate and metabolism.[17]

The climbing ability of the Alpine ibex is such that it has been observed scaling the Cingino Dam in Piedmont, Italy, where it licks the artificial salts. Only females and young (kids) will climb the steep dam due to their lighter weight and shorter legs. Kids have been recorded to reach heights of 49 m (161 ft), ascending in a zig-zag path on gradients of up to 155% while descending in straight lines at 157% gradients. They move along the dam by walking and galloping.[18]

Social life

Although the Alpine ibex is a social species, they tend to live in separate groups based on sex and age.[3] For most of the year, adult males group separately from females, and older males live separately from younger males.[19] Dependent kids live with their mothers in female groups. Segregation between the sexes is a gradual process and males younger than nine years old may still associate with female groups.[20] Adult males are also more likely to be found alone than females, particularly older males.[21] Social spacing tends to be looser in the summer, when there is more room to feed. Males in particular have stable social connections and consistently regroup with the same individuals when ecological conditions force them back together.[22]

Adult males and females gather during the breeding between December and January. By April and May, the adults separate again.[3] A dominance hierarchy exists among males based on size, age and horn length.[23] Hierarchies are established outside the breeding season, allowing males to focus more on mating and less on fighting. Males use their horns for combat, and will hit their opponent in the side or clash head-to-head, the latter often involves them standing bipedally and clashing downward.[24]

Alpine ibex communicate mainly through whistles, described as "short and sharp". They primarily serve as alarm calls and make be produced singularly or in succession with short gaps. Females and their young communicate by bleating.[7]

Reproduction and growth

The mating season begins in December, and typically lasts around six weeks. During this time, male herds break up into smaller groups that search for females. The rut takes place in two phases. In the first phase, the males interact with the females as a group. In the second phase, one male separates from his group to follow an individual female in oestrous.[3] Dominant, older males (9–12 year olds) will follow and guard a female from rivals, while more subordinate, younger males (2–6 year olds) will try to sneak pass the tending male when he is distracted. If a female flees, both dominant and subordinate males will try to follow her. During courtship, a male may stretch the neck, flick the tongue, curl the upper lip, urinate and sniff the female.[25] After copulation, a male rejoins his group and restarts the first phase of the rut.[3]

Females are in oestrous for around 20 days, while gestation averages around five months, and results in the birth of one but sometimes two kids.[26] Females give birth away from their social groups and on rocky slopes which are relatively safe from predators.[27] After a few days, the kids can already move on their own. Mothers and kids gather into nursery groups. Female nurse their young for up to five months.[7] Alpine ibex reach sexual maturity at 18 months, but females continue to grow for until they are around five or six years old, and males around nine or eleven years old.[3] Males live for 16 years while females live 20 years. The species has a particularly high adult survival rate compared to other herbivores around its size. In one study, all kids reached two years of age and the majority of adults lived to 13 years, though most 13-year-old males did not reach the age of 15.[28]

The horns grow throughout life. Young are born without horns; they are visible as tiny tips by one month and grow up to 20–25 mm (0.79–0.98 in) by two months.[7] In males. the horns grow at about 8 cm (3.1 in) a year for the first five-and-a-half years, eventually slowing to half that rate once the animal reaches 10 years of age.[3] The slowing down of horn growth coincides with aging in males.[29]

Mortality

Alpine ibex appear to have a low rate of predation.[3] Their mountain habitat keeps them safe from predators like wolves, though golden eagles may prey on young.[7] In Gran Paradiso, sources of mortality are old age, lack of food, and disease.[3] The species may suffer necrosis and fibrosis caused by the bacteria Brucella melitensis,[30] and foot rot caused by Dichelobacter nodosus.[31] Ibex can host gastrointestinal parasites, mainly coccidia and strongyles,[32] and lungworms, mainly Muellerius capillaris.[33]

Conservation

During the Middle Ages, the Alpine ibex ranged throughout the Alpine region of Europe.[8] Starting in the early 16th century, the overall population declined due almost entirely due to hunting and poaching by humans, particularly with the introduction of firearms. Ibex where exploited mainly for traditional medicine and a single carcass could create multiple different remedies.[34] By the 19th century, the species survived only in and around the Gran Paradiso in northwestern Italy with a population of 100 individuals.[3][34]

Hunting of the ibex has banned in 1821 by the local government of Piedmont and the park was declared a royal hunting reserve in 1854 by Victor Emmanuel II.[3][7] Since 1902, several ibex from the Gran Paradiso were taken into captive facilities in Switzerland for selective breeding and reintroductions into the wild. Until 1948, translocated founders were captive-bred. Afterwards, reintroductions were done with wild-born specimens from established populations in Piz Albris, Le Pleureur and Augstmatthorn. This would be the case for populations in France and Austria. In the late 20th century, the original Gran Paradiso population was used for reintroductions into other parts of Italy.[34] Ibex would also recolonise areas on their own.[3] The total Alpine ibex population reached 3,020 in 1914, 20,000 in 1991 and 55,297 in 2015, and by 1975, the species occupied much of its medieval range.[3][8][34]

Between 2015 and 2017, there were around 9,000 ibexes in 30 colonies in France, over 17,800 individuals and 30 colonies in Switzerland, over 16,400 ibex in 67 colonies in Italy, around 9,000 in 27 colonies in Austria, around 500 in five colonies in Germany and almost 280 ibexes and four colonies in Slovenia.[8] As of 2020, the Alpine ibex considered to be of Least Concern by the IUCN with a stable population trend. It was given a recovery score of 79%, making it "moderately depleted". While the species would likely have gone extinct without historic conservation efforts, as of 2021 it has low conservation dependence. The IUCN assesses that without current protections, the population decline of the species would be minimal.[1]

However, having gone through a genetic bottleneck, they have low genetic diversity and are at risk of inbreeding depression.[1][35] A 2020 analysis found that highly deleterious mutations were lost in these new populations but they but also gained mildly deleterious ones.[36] The genetic integrity of the species may also be threatened by hybridization with domestic goats, which have been allowed to roam in their habitat.[37] The genetic bottleneck of populations may increase vulnerability to infectious diseases due to low major histocompatibility complex diversity.[38] In the Bornes Massif region of the French Alps, management actions, including a test-and-cull program (a method to control outbreaks), effectively reduced Brucella infection prevalence in adult females from 51% in 2013 to 21% in 2018, with active infections also declining significantly.[39]

References

- 1 2 3 Toïgo, C.; Brambilla, A.; Grignolio, S.; Pedrotti, L. (2020). "Capra ibex". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T42397A161916377. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T42397A161916377.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ García–González, R; Herrero, J; Nores, C (2021). "The names of southwestern European goats: is Iberian ibex the best common name for Capra pyrenaica?". Animal Biodiversity and Conservation. 44 (1): 1–16. doi:10.32800/abc.2021.44.0001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Parrini, F.; Cain III, J. W; Krausman, P. R. (2009). "Capra ibex (Artiodactyla: Bovidae)". Mammalian Species (830): 1–12. doi:10.1644/830.1.

- 1 2 Pidancier, N; Jordan, S; Luikart, G; Taberlet, P (2006). "Evolutionary history of the genus Capra (Mammalia, Artiodactyla): Discordance between mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome phylogenies". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (3): 739–749. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.04.002.

- ↑ Shackleton, D. W (1997). Wild Sheep and Goats and Their Relatives: Status Survey and Action Plan for Caprinae. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Species Survival Commission. Caprinae Specialist Group. p. 12. ISBN 2831703530.

- ↑ Robin, M; Ferrari, G; Akgül, G; Münger, X; von Seth, J; Schuenemann, V. J; Dalén, L; Grossen, C (2022). "Ancient mitochondrial and modern whole genomes unravel massive genetic diversity loss during near extinction of Alpine ibex". Molecular Ecology. 31 (13): 3548–3565. doi:10.1111/mec.16503.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brambilla, A; Bassano, B; Biebach, I; Bollmann, K; Keller, L; Toïgo, C; von Hardenberg, A (2022). "Alpine Ibex Capra ibex Linnaeus, 1758". In Corlatti, L; Zachos, F. E (eds.). Terrestrial Cetartiodactyla - Handbook of the Mammals of Europe. Springer. pp. 383–408. ISSN 2730-7387.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bramnilla, A; von Hadenberg; Nelli, L; Bassono, B (2020). "Distribution, status, and recent population dynamics of Alpine ibex Capra ibex in Europe". Mammal Review. 40 (3): 267–277. doi:10.1111/mam.12194.

- ↑ Geskos, A (2013). "Past and present distribution of the genus Capra in Greece". Acta Theriologica. 58: 1–11. doi:10.1007/s13364-012-0094-9. S2CID 256122729.

- 1 2 3 Grignolio, S; Parrini, F; Bassano, B; Luccarini, S; Apollonio, M (2003). "Habitat selection in adult males of Alpine ibex, Capra ibex ibex" (PDF). Folia Zoologica. 52 (2): 113–20.

- ↑ ToÏgo, C.; Gaillard, J. M; Michallet, J (1997). "Adult survival pattern of the sexually dimorphic Alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 75: 75–79. doi:10.1139/z97-009.

- 1 2 Grignolio, S; Rossi, I; Bassano, B; Parrini, F; Apollonio, M (2004). "Seasonal variations of spatial behaviour in female Alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex) in relation to climatic conditions and age". Ethology Ecology and Evolution. 16 (3): 255–264. doi:10.1080/08927014.2004.9522636. S2CID 85380031.

- ↑ Wiersema, G (1984). "Seasonal use and quality assessment of ibex habitat". Acta Zoologica Fennica. 172: 89–90.

- ↑ Neuhaus, P; Ruckstuhl, K. E (2002). "Foraging behaviour in Alpine ibex (Capra ibex): consequences of reproductive status, body size, age and sex". Ethology Ecology & Evolution. 14 (4): 373–381. doi:10.1080/08927014.2002.9522738.

- ↑ Aublet, J-F; Festa-Bianchet, M; Bergero, D; Bassano, B (2009). "Temperature constraints on foraging behavior of male Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) in summer". Oecologia. 159 (1): 237–247. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1198-4.

- ↑ Parrini, F; Grignolio, S; Luccarini, S; Bassano, B; Apollonio, M (2003). "Spatial behaviour of adult male Alpine ibex Capra ibex ibex in the Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy". Acta Theriologica. 48 (3): 411–423. doi:10.1007/BF03194179. S2CID 6211702.

- ↑ Signer, C; Ruf, T; Arnold, W (2011). "Hypometabolism and basking: the strategies of Alpine ibex to endure harsh over-wintering conditions". Functional Ecology. 25 (3): 537–547. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01806.x.

- ↑ Biancardi, C. M; Minetti, A. E (2017). "Gradient limits and safety factor of Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) locomotion". Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy. 28 (1): 56–60. doi:10.4404/hystrix-28.1-11504.

- ↑ Bon, R; Rideau, C. S; Villaret, J-C; Joachim, J (2001). "Segregation is not only a matter of sex in Alpine ibex, Capra ibex ibex". Animal Behaviour. 62 (3): 495–504. doi:10.1006/anbe.2001.1776.

- ↑ Villaret, J. C; Bon, R (1995). "Social and spatial segregation in Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) in Bargy, French Alps". Ethology. 101 (4): 291–300. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1995.tb00366.x.

- ↑ Villaret, J-C; Bon, R (1998). "Sociality and relationships in Alpine ibex (Capra ibex)". Revue d'Écologie.

- ↑ Brambilla, A; von Hardenberg, A; Canedoli, C; Brivio, F; Sueur, C; Stanley, C. R (2022). "Long term analysis of social structure: evidence of age-based consistent associations in male Alpine ibex". Oikos (8): e09511. doi:10.1111/oik.09511.

- ↑ Bergeron, P; Grignolio, S; Apollonio, M; Shipley, B; Festa-Bianchet, M (2010). "Secondary sexual characters signal fighting ability and determine social rank in Alpine ibex (Capra ibex)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 64 (8): 1299–1307. doi:10.1007/s00265-010-0944-x.

- ↑ Willisch, C. S; Neuhaus, P (2010). "Social dominance and conflict reduction in rutting male Alpine ibex, Capra ibex". Behavioural Ecology. 21 (2): 372–380. doi:10.1093/beheco/arp200.

- ↑ Willisch, C. S; Neuhaus, P (2009). "Alternative mating tactics and their impact on survival in adult male Alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex)". Journal of Mammalogy. 90 (6): 1421–1430. doi:10.1644/08-MAMM-A-316R1.1.

- ↑ Stüwe, M; Grodinsky, C (1987). "Reproductive biology of captive Alpine ibex (Capra i. ibex)". Zoo Biology. 6 (4): 331–339. doi:10.1002/zoo.1430060407.

- ↑ Grignoli, S; Rossi, I; Bertolotto, E; Bassano, B; Apollonio, M (2007). "Influence of the kid on space use and habitat selection of female Alpine ibex". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 71 (3): 713–719. JSTOR 4495243.

- ↑ ToÏgo, C; Gaillard, J-M; Festa-Bianchett, M; Largo, E; Michallet, J; Maillard, D (2007). "Sex- and age-specific survival of the highly dimorphic Alpine ibex: evidence for a conservative life-history tactic". Journal of Animal Ecology. 76 (4): 679–686. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01254.x. PMID 17584373.

- ↑ von Hardenberg, A; Bassano, B; del Pilar Zumel Arranz, M; Bogliani, G (2004). "Horn growth but not asymmetry heralds the onset of senescence in male Alpine ibex (Capra ibex)". Journal of Zoology. 263 (4): 425–432. doi:10.1017/S0952836904005485.

- ↑ Ferrogilo, E; Tolari, F; Bassano, B (1998). "Isolation of Brucella melitensis from alpine ibex". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 34 (2): 400–402. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-34.2.400.

- ↑ Moore-Jones, G; Dürr, S; Willisch, C; Ryser-Degiorgis, M–P (2021). "Occurrence of footrot in free-ranging alpine ibex (Capra ibex) colonies in Switzerland". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 57 (2): 327–337. doi:10.7589/JWD-D-20-00050.

- ↑ Carcereri, A; Stancampiano, L; Marchiori, E; Sturaro, E; Ramanzin, M; Cassini, R (2021). "Factors influencing gastrointestinal parasites in a colony of Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) interacting with domestic ruminants". Hystrix, the Italian Journal of Mammalogy. 32 (1): 95–101. doi:10.4404/hystrix-00393-2020.

- ↑ Cassini, R; Párraga, M. A; Signorini, M; Frangipane di Regalbono, A; Sturaro, E; Rossi, L; Ramanzin, M (2015). "Lungworms in Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) in the eastern Alps, Italy: An ecological approach". Veterinary Parasitology. 214 (1–2): 132–138. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.09.026.

- 1 2 3 4 Stüwe, M; Nievergelt, B (1991). "Recovery of Alpine ibex from near extinction: the result of effective protection, captive breeding, and reintroductions". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 29 (1–4): 379–87. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(91)90262-V.

- ↑ Biebach, I.; Keller, L. F (2009). "A strong genetic footprint of the re-introduction history of Alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex)". Molecular Ecology. 18 (24): 5046–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04420.x. PMID 19912536. S2CID 36215646.

- ↑ Grossen, C; Guillaume, F.; Keller, L. F; Croll, D (2020). "Purging of highly deleterious mutations through severe bottlenecks in Alpine ibex". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 1001. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14803-1. PMC 7035315. PMID 32081890.

- ↑ Moroni, B; Brambilla, A; Rossi, L; Meneguz, P. G; Bassano, B; Tizzani, P (2022). "Hybridization between Alpine ibex and domestic goat in the Alps: a sporadic and localized phenomenon?". Animals. 12 (6): 751. doi:10.3390/ani12060751.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ↑ Brambilla, A; Keller, L; Bassuno, B; Grossen, C (2017). "Heterozygosity–fitness correlation at the major histocompatibility complex despite low variation in Alpine ibex (Capra ibex)". Evolutionary Applications. 11 (5): 631–644. doi:10.1111/eva.12575.

- ↑ Calenge, C; Lambert, S; Petit, E; Thébault, A; Gilot-Fromont, E; Toïgo, C; Rossi, S (2021). "Estimating disease prevalence and temporal dynamics using biased capture serological data in a wildlife reservoir: The example of brucellosis in Alpine ibex (Capra ibex)". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 187: 105239. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105239.