| |

| Author | |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Popular science |

| Publisher | Penguin Press |

Publication date | November 7, 2023 |

| Pages | 436 |

| ISBN | 9781984881724 |

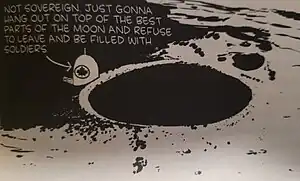

A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? is a 2023 popular science book by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith. It covers the current state of knowledge of space settlement given changes in the economics of space travel in the 2010s and 2020s, with a particular focus on challenges that remain unresolved or underestimated in the authors' opinions. The book is illustrated with Zach's artwork; he is known as the cartoonist of the webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal.

The Weinersmiths catalog challenges facing space settlement and create a to-do list of research and negotiation to potentially solve or mitigate them. The Weinersmiths are skeptical of attempting to move too quickly, and warn that the challenges facing long-term human existence in space remain profound. They write that some of the technical barriers to increased space travel appear to be weakening due to advances from commercial space flight providers, but caution that major work remains dangerously incomplete. In particular, they discuss sex in space; pregnancy and raising children off-Earth; space psychology; the effect of microgravity on the human body; the effects of deep space radiation on humans outside the protection of Earth's magnetosphere; agriculture using toxic Martian soil and preserving a livable biosphere in general; space law; nation-building off-Earth; and the difficulties of resupply. They also caution that the benefits from colonization of the Moon, colonization of Mars, and building gigantic spinning space stations remain quite weak, with even a hypothetically devastated Earth after multiple future apocalypses being a paradise compared to other options in the Solar System. Despite this, the Weinersmiths remain cautiously interested in continuing space settlement projects; they describe themselves as "guardrails" rather than "barriers", and suggest that their main message is the necessity of performing far more groundwork first for such plans to ultimately succeed.

Reviews of the book were positive, praising its humor and fresh viewpoint. It made 11th place on The New York Times Best Seller list for hardback non-fiction books.

Background

The authors are a married couple: Kelly Weinersmith is an adjunct professor at Rice University in the BioSciences Department, and Zach Weinersmith is a cartoonist who draws the webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal. The idea behind the book originated while the Weinersmiths were writing the 2017 book Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That'll Improve and/or Ruin Everything. The first chapter of Soonish is on cheap access to space. In 2017, a Falcon Heavy rocket could raise mass to low earth orbit for around $1500 a kilogram, a sharp price decrease compared to the 20th century. With statements by the likes of Elon Musk on how a Mars colony was just around the corner in 2030, the two researched what the near future of space settlement might be like, expecting to write a book on how to pick the crew and the like. As their research continued, the challenges appeared far more daunting and unresolved than expected. The two compare the existing situation of popular space literature to if all the books on beer were written by brewing companies: space books are usually written by enthusiasts and advocates of space colonization. They decided to cut against the grain and try to popularize these barriers instead, if in a humorous and accessible fashion, taking the moniker of "Space Bastards" for themselves.[1][2]

The book was published on November 7, 2023, by Penguin Press, a division of Penguin Books.[3]

Contents

The authors discuss many of the common reasons proposed for space settlement, finding most of them inadequate. The overview effect, said to make astronauts wise and insightful, appears to be very minor if it exists at all; historians no longer hold to the Frontier Thesis that suggests a rugged place to explore and conquer like the American West necessarily creates hardy, productive, democratic citizens (as in the "New Frontier" invoked by President Kennedy); and the political reasons for the original Space Race no longer hold — it took place side-by-side with decolonization, where there was a contest for prestige between the US and USSR to impress newly formed countries to take their side.[4]

The two arguments that the Weinersmiths grant have power are spreading humanity out in the interests of long-term survival, as well as seeing space simply as a luxury investment to do for no deeper reason than because it's awesome.[4] The Weinersmiths examine current plans for space settlement, as well as areas they believe to be neglected in popular knowledge. A selection of these topics include:

Human physiology

Our current knowledge of the health impacts on humans of prolonged exposure to low gravity and cosmic rays remains limited, yet is alarming. Even with astronauts performing mandated exercise and staying for a comparatively short length of time, they often report steep muscle loss and other changes from the low gravity environment, such as lower back pain. The longest any human has spent consecutively in orbit is 437 days (held by Valeri Polyakov), and the longest a human has been in deep space exposed to cosmic radiation without the protection of the Earth's magnetosphere was only 12 days, yet merely one way on a trip to Mars takes six months using current technology. Any trip back would be strictly limited by launch windows for when gravity assists line up, suggesting that even the fastest of Mars jaunts by humans would require spending an exceptionally long time in space. The survivability of such trips, as well as long-term impacts on the human body, are a major question — depending on the kind of Mars settlement, it is possible that "Martians" would be unable to ever safely return to Earth. Blocking radiation is not trivial; incompetently arranged shielding can make radiation even worse, suggesting that only living underground would provide anything like the protection received on Earth from radiation. Astronauts have also reported damage to eyesight, hypothesized to be from radiation.[5]

Issues often glossed over, but important to a truly long-term human settlement in space, are sex in space, pregnancy, and children. Is it safe or possible to have and raise children in a low-gravity environment such as Mars? It has been suggested that even if it is not, "artificial" gravity could be created, but this leads to its own problems. Hypothetically, a banked racetrack (or "pregnodrome") could be used to constantly accelerate humans downward to Earth-equivalent gravity, but are a mother and child really going to live in some sort of train for 18 years and 9 months? What happens if the vehicle breaks? The problem is even worse for the gravity of the Moon, which is even weaker than Mars.[6]

Nature of proposed settlements

An Earth with climate change and nuclear war and, like, zombies and werewolves is still a way better place than Mars. Staying alive on Earth requires fire and a pointy stick. Staying alive in space will require all sorts of high-tech gadgets we can barely manufacture on Earth.

A City on Mars, Chapter 1

The Weinersmiths examine what settlements would be like if made. They emphasize that Mars is not a luxurious escape for rich vacationers. Rather, life on Mars would likely be an experience of living underground in tight quarters with little personal space, carefully recycling every drop of carbon including human excrement, eating crickets and drinking beet juice, with mechanical mishaps and failures being potentially deadly. Giant dust storms can cover the entire surface for weeks on Mars. Major questions remain; Martian soil is tainted by perchlorates. Would it be possible to safely grow food with it that would not be similarly tainted? The Moon is even worse, with solely regolith for its surface (equivalent to small shards of glass, far worse than Earth soil), and almost completely lacking in carbon as well as other elements essential to human life such as phosphorus. Finally, giant rotating space stations would at least be able to simulate Earth gravity, but would be completely exposed to radiation, and would require immense amounts of mass to build safely, suggesting a Moon base and a way to build such a structure from mass taken from asteroids or the Moon would be prerequisites to such an endeavor.[7]

Space psychology also arises as a topic. Current space missions simply use selection to only send the most rock-solid reliable types into space as astronauts, but a major settlement effort would presumably not be able to be as choosy. Would average people be able to adapt to the hardships of space? If someone became irrational, would there be ways to safely restrain them and cover for them? The Weinersmiths examine the closest cases on Earth, involving people cooped up in Antarctica, but even there, rescue and a ride to civilization was possible in the realm of days, rather than months. They also consider the Biosphere 2 experiment, where eight people lived in a tightly controlled ecosystem for a year. While the project lost money, its cost was a tiny fraction compared to the budget of the International Space Station, and suggest that hundreds of similar Biosphere-type experiments could be productively and cheaply run on Earth.[8]

Sociology, law, and politics

The topic of survival homicide is explored: what would happen if, in the event of an emergency, food and air would better be preserved by killing off some crew members or settlers? And possibly even eating them? Existing precedents such as US v. Holmes and R v Dudley and Stephens are brought up, as well as the likelihood that space settlement would probably proceed under the laws of whichever nation's citizens were sent.[9] The Weinersmiths also suggest that it is imperative to avoid intentionally creating ethically dubious situations. Space settlement isn't an unplanned disaster like a shipwreck or a mine collapse. If a country was considering sending a group of settlers off to Antarctica, and were warned that if left on their own for a long time they may start treating human life rather cavalierly (e.g. executing the sick, weak, or disabled to conserve scarce resources), the authors say we should not treat that as a cute sociological quirk, but rather a signal that it's not safe to send the settlers yet.

The Outer Space Treaty is discussed, both with what it says and what it doesn't cover (but perhaps should). The OST was written in an era when there were only two major space powers, but the authors consider it in need of an update for the 2020s era of commercial space exploration. Additionally, while the authors are skeptical of the economic case for space (e.g. asteroid mining, hypothetical Helium-3 extraction on the Moon, etc.), if it turns out there really is an economic case for space, they fear it may weaken some of the norms that have kept space exploration peaceful so far, increasing even further the importance of updating global standards on the matter.[10]

Finally, certain aspects of space settlement suggest that if done with only small populations, the governance style would naturally shift toward authoritarianism, given the strict control of machinery and recycling required for survival. While workers can generally leave an unpleasant company town on Earth at worst, this is substantially dicier on a hypothetical small Mars settlement, where there may be no other place to go, and the bosses control everything about life. This would suggest not making a settlement until ready to "go big" and send a substantial population at once, allowing for redundancy if people quit or die or machines break, given the long travel times to Earth. And while advanced technology is mostly a good thing for space settlement, it still raises its own risks. Powerful future technology to, say, efficiently return material from the Moon to the Earth or perform asteroid mining would also be an extremely potent weapon.[11]

Conclusions

The authors caution that the difficulties in achieving autarky (that is, true economic self-sufficiency with no need for Earth) remain huge, weakening the case for the first rationale of human survival. Autarky may be distant-to-impossible, requiring millions of thriving settlers or incredibly advanced hypothetical robotics to even consider. The second rationale of "because it's awesome" is only moral if it is also safe. This would likely require biology and ecology research to study and protect humans in space. It would also require aligning spacefaring nations on a new political and legal framework first to avoid the risk of starting World War III in space.[12]

Reception

Critical reception to A City on Mars was positive. W. M. Akers wrote in The New York Times that the book was "exceptional" and "hilarious", praising it as a needed check on expectations of space settlement coming any time soon.[13] Christie Aschwanden of Undark said the book was "deeply researched", informative, and interesting.[14] Kim Kovacs of BookBrowse thought that A City on Mars was deeper than the average pop science book, with its humor helping let laypeople follow along with the cutting edge of space technology.[15] Kirkus Reviews called the book "a romp" with a lot to offer.[3] Chris Lee of Ars Technica praised the book for raising the risks of not taking seriously the political structure of a future space settlement, writing "do you really want to create a group of hungry, disgruntled miners that are also able to sling very large rocks at the Earth?"[16]

A City on Mars made 11th place on The New York Times Best Seller list for hardback non-fiction books.[17]

References

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, Introduction

- ↑ Kuthunur, Sharmila (November 8, 2023). "'A City on Mars' is a reality check for anyone dreaming about life on the Red Planet". Space.com. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- 1 2 "A City on Mars". Kirkus Reviews. May 27, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- 1 2 Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, 1. A Preamble on Space Myths

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, 2. Suffocation, Bone Loss, and Flying Pigs: The Science of Space Physiology

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, 3. Space Sex and Consequences Thereof

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, Part II: Spome, Spome on the Range: Where will Humans Live Off-World?

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, 4. Spacefarer Psychology: In Which the Only Thing We're Sure of is That Astronauts are Liars; Part III: Pocket Edens: How to Create a Human Terrarium That Isn't All That Terrible

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, Nota Bene: Space Cannibalism From a Legal and Culinary Perspective

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, 12. The Outer Space Treaty: Great for Regulating Space Sixty Years Ago

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, Part VI: To Plan B or Not to Plan B: Space Society, Expansion, and Existential Risk

- ↑ Weinersmith & Weinersmith 2023, Conclusion: Of Hot Tubs and Human Destiny

- ↑ Akers, W. M. (October 28, 2023). "Is It Time to Pull Up Stakes and Head for Mars?". The New York Times. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Aschwanden, Christie (November 10, 2023). "Book Review: Are We Ready to Head to Mars? Not So Fast". Undark Magazine. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Kovacs, Kim (November 15, 2023). "A City on Mars". BookBrowse. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ Lee, Chris (November 20, 2023). "A City on Mars: Reality kills space settlement dreams". Ars Technica. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Hardcover Nonfiction (November 26, 2023)". The New York Times. November 2023.

Further reading

- Weinersmith, Kelly; Weinersmith, Zach (2023). A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?. Penguin Press. ISBN 9781984881724. LCCN 2022951665.

- Weinersmith, Kelly; Weinersmith, Zach (November 5, 2023). "Space Billionaires Should Spend More Time Thinking About Sex". The New York Times. Retrieved November 21, 2023. (excerpt)