| Þorbjörn | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Þorbjörn | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 243 m (797 ft)(Íslandshandbókin. Náttúra, saga of sérkenni. Reykjavík 1989, p. 65) |

| Coordinates | 63°51′54″N 22°26′12″W / 63.86500°N 22.43667°WVisit Reykjavík. Official Website. |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Bear of Thor |

| Language of name | Icelandic |

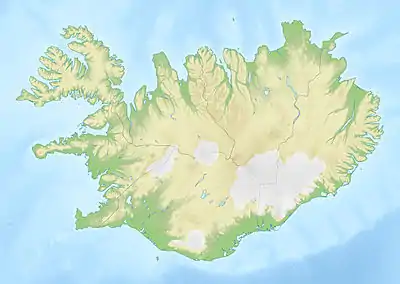

| Geography | |

Þorbjörn | |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Pleistocene |

| Mountain type | Tuya |

| Last eruption | Pleistocene |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | jeep track |

Þorbjörn (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈθɔrˌpjœ(r)tn̥]) is a volcanic mountain of 243 m next to the town of Grindavík (Gullbringusýsla) on Reykjanes peninsula, Iceland.[1] Blue Lagoon can be easily seen from the summit.

Name

The name of Þorbjörn or Þorbjarnarfell [ˈθɔrˌpja(r)tnarˌfɛtl̥], the “mountain of Þorbjörn” which is still a popular man's name in Iceland, is connected with the son of a farmer in the region. When a group of bandits were tyrannizing the farmers in the area and disappeared into hiding every time after their raids, the young man had the idea of playing to be part of the group. In this way, he found out that their hiding place was in a cave within the mountain, and the bandits were taken and hanged.[2] Since then, the small canyon within the mountain is called “Thieves’ Canyon” (Þjófagjá [ˈθjouː(v)aˌcauː]).[1]

History

When the U.S. Army arrived in Iceland during World War II, a jeep track was built up onto the mountain, which remains to this day. Transmitters from the telephone company Sími and Icelandic National Television RÚV now occupy the site where the U.S. Army had previously installed some radar stations.[3] These were given over to the Icelandic Government when the US Army left the country in 2006.

Geography

The mountain is situated near the tip of Reykjanes peninsula between Svartsengi Power Station with the Blue Lagoon and the town of Grindavík at road 43 (to the east), whereas another road, route 426, goes round it from Grindavík to Svartsengi on its western side.

Geology

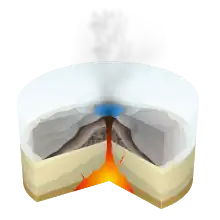

Þorbjörn originates from subglacial eruptions during a cold spell in the Pleistocene.

It is located within the area of the Reykjanes volcanic system and enclosed by Holocene lava fields. In addition, a visible tectonic graben[4] runs over the top of the mountain.[5] It builds a small canyon, up to 80 m deep.[6] As such, the mountain is a symbol of Reykjanes' geology in the whole.[7]

The subglacial volcano is located within the area of the Reykjanes volcanic system[8] or Svartsengi volcanic system,[9] depending on author.

Pleistocene volcanoes on Reykjanes peninsula

Pleistocene volcanism on the Reykjanes peninsula is represented esp. by bigger edifices, i.e. shield volcanoes and subglacially formed ridge volcanoes or tuyas.

When analyzing aerial photographs of shield volcanoes and glaciovolcanic edifices, it becomes clear that the latter have much steeper slopes than the shields.[5]

On Reykjanes, all kinds of subglacial volcanoes are to be found, tindars, also called subglacial mounds, originating in fissure eruptions under glaciers, flat-topped tuyas (see Geitahlíð), complex tuyas and even conical tuyas (Keilir).[5]

Tindars/subglacial mounds/hyaloclastic ridges originate from subglacial fissure eruptions which never saw the light of day. Only after the Pleistocene glaciers were gone and the sea level down, these mountains now can be researched.

Whereas the magma of tuyas has more pressure, viscosity or volume so that in the end the edifice which builds up first subglacially in a lake of its own meltwater, pushes in the end through the water and ice to build up some tephra and/or lava layers on top as well as lava deltas at its slopes.[10]

Formation of the tuya Þorbjörn

It also built up in an melt water lake so that Pedersen etal. define it as “a pillow-dominated flat-topped tuya without a lava cap”.[5] H. Björnsson explains that though the mountain is crossed by many faults and a graben, so that it looks like a complex formation, it has its origin in a single eruption.[4]

The pillows are formed and cooled in two stages: First the lava touches water and cools down very fast, in a second step after some pillow layers have formed, the melt water lake or water (if the eruption is underwater in the sea or a lake) cools it down further. On the other hand, it only depends on the magma pressure if the eruption turns explosive and forms hyaloclastite or not.[4]

In the top region of Þorbjörn, there is also a rather eroded crater, but probably because of the erosion, no trace of subaerial lavas has been found.[4]

The tuya is slightly elongated in the direction of the volcanic fissure systems of Reykjanes, i.e. southwest to northeast.[11]

2020–present activity

_-_Aug_2022.jpg.webp)

As is often the case on Reykjanes peninsula, swarms of small earthquakes and associated ground uplift, thought to be linked to magma intrusions, begain in the region in 2020, and again in 2023.[12]

In January 2020, the instruments of IMO (the Icelandic Met Office, in Icelandic: Veðurstofa Íslands) and other volcano monitoring stations showed ground uplift around and to the west of Þorbjörn. The uplift stopped after some time and then started again. Together with repeated earthquake swarms in the region, but also at the tip of Reykjanes peninsula (Gunnuhver, Sudurnes Geothermal Power Station) as well as under Fagradalsfjall which probably is part of Krýsuvík volcanic system, but sometimes also seen as an independent volcanic system, more uplift and earthquakes were measured and where three smaller volcanic eruptions took place in the years 2021, 2022 and 2023. The volcano-tectonic movements which seem to touch a rather big area are still ongoing in November 2023.[13]

Up to now the following pattern shows:

- end of January 2020: uplift and earthquakes around Þorbjörn; 3–4 mm per day,[14] but gas measurements don't indicate magmatic intrusions near the surface.[15]

- mid February 2020: uplift at Þorbjörn stops[16]

- 12 March 2020: A rather heavy earthquake took place not far from Grindavík, it was first measured at 5.2 M,[16] but corrected down to 4.6 M later on [17]

- 17 March 2020: Uplift was measured again at Þorbjörn. But it was slower now. The uplift could be caused by rising magma, but such intrusive events can repeat itself for a rather long time, even years, without any eruptions.[17]

- 2 April 2020: A new intrusion was discovered on Reykjanes, in this case at Sýrfell under the tip of the peninsula, i.e. some km to the west of Þorbjörn.[18] It stopped in the middle of the month.[18]

- These were the results of an interdisciplinary conference in Iceland on 8 April 2020:

From January to mid April 2020, around 8 000 earthquakes were registered at the Reykjanes peninsula. This was the most important earthquake series in this region since earthquakes were first measured there. At the same time, uplift was about 10 cm around Þorbjörn caused by a magmatic intrusion, a sill, at a depth of 3–4 km. Another intrusion was found around the tip of the peninsula under the mountain Sýrfell. It lies deeper at about 8–13 km which means at the border between crust and mantle in this region. The third one was again to be found near Þorbjörn and uplift was not yet terminated by mid-April 2020. Uplift and intrusion had started on 6 Mars 2020. It is thought to be another sill, this time at a depth of 3 km, but uplift is much slower than with the first intrusion there. The earthquakes are thought to result from strain release. On Reykjanes peninsula, earthquake series are not seldom. There was a lot of activity, for instance from 1927 to 1955 and from 1967 to 1977, including a 6.3 M earthquake in 1929 and a 6.0 in 1968, both within the Brennisteinsfjöll.[19]

- End of May, beginning of June 2020: Over 700 – mostly small earthquakes were measured around Þorbjörn. Uplift started again around the mountain.[18]

- End of July 2020: Another earthquake series took place in the region, this time, the hypocentre was below the mountain Fagradalsfjall. Movements were measured at a known fault. The region is well known for repeated earthquake series. In Svartsengi was registered at the same time a small subsidence.[9]

The newest events are interpreted as part of the overall volcano-tectonic activity registered on Reykjanes since 2019. This involves four volcanic systems: Eldey (a small island on Reykjanes Ridge, most of the system is submarine), Reykjanes, Svartsengi Volcanic System (often seen as part of the Reykjanes system) and Krýsuvík.[9]

Reykjanes peninsula is volcano-tectonically very active. It is the part of Iceland where the island is connected to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The last bigger eruption series in this region took place in the 13th century and was called the Reykjanes Fires (1220-1240)[20]

Hiking

Some hiking trails lead onto the mountain, e.g. from the southwest.[7]

See also

External links

References

- 1 2 Íslandshandbókin. Náttúra, saga of sérkenni. Reykjavík 1989, p. 65

- ↑ Reynir Ingibjartsson: 25 Gönguleiðir á Reykjanesskaga. Náttúrann við Bæjarveggin. Reykjavík , p. 74

- ↑ Reynir Ingibjartsson: 25 Gönguleiðir á Reykjanesskaga. Náttúrann við Bæjarveggin. Reykjavík , pp. 70-72

- 1 2 3 4 Haukur Björnsson: Myndun Þorbjarnarfells. BS ritgerð. Leiðbeinandi Ármann Höskuldsson. Jarðvísindadeild Háskóli Íslands 2015 (in Icelandic, abstract also in English)

- 1 2 3 4 Pedersen, G. B. M.; Grosse, P. (August 1, 2014). "Morphometry of subaerial shield volcanoes and glaciovolcanoes from Reykjanes Peninsula, Iceland: Effects of eruption environment". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 282: 115–133. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.06.008 – via ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Reynir Ingibjartsson: 25 Gönguleiðir á Reykjanesskaga. Náttúrann við Bæjarveggin. Reykjavík , p. 72

- 1 2 Reynir Ingibjartsson: 25 Gönguleiðir á Reykjanesskaga. Náttúrann við Bæjarveggin. Reykjavík , pp. 70-75

- ↑ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskuldsson: Iceland. Classic geology of Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, p.14

- 1 2 3 Veðurstofa Íslands: Jarðskjálftavirknin við Fagradalsfjall fer dvínandi.(23.7.2020) Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Edwards, B.R., Gudmundsson, M.T., Russell, J.K., 2015. Glaciovolcanism. In: Sigurdsson, H., Houghton, B., Rymer, H., Stix, J., McNutt, S. (Eds.), The Encyclopedia of Volcanoes, pp. 377–393.

- ↑ See maps, eg. in: Reynir Ingibjartsson: 25 Gönguleiðir á Reykjanesskaga. Náttúrann við Bæjarveggin. Reykjavík , p. 71

- ↑ "Swarm of earthquakes in Iceland heralds next volcanic eruption". October 27, 2023 – via The Guardian.

- ↑ {{Cite web|url=https://en.vedur.is/about-imo/news/a-seismic-swarm-started-north-of-grindavik-last-night%7Ctitle=High likelihood of volcanic eruption continues|date=November 19, 2023|via=Icelandic Met Office} Retrieved: 19 November 2023.}

- ↑ Veðurstofa Íslands: Áfram þensla við fjallið Þorbjörn og landris komið í rúma þrjá sentimetra. (28.1.2020) Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Veðurstofa Íslands: Ný gögn sýna áframhaldandi landris á svæðinu við Þorbjörn. Nýjar gasmælingar gefa engar vísbendingar um að kvika sé komin nálægt yfirborð. (29.1.2020) Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- 1 2 Veðurstofa Íslands:Stór skjálfti við Grindavík (12.3.2020) Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- 1 2 Veðurstofa Íslands: Landris hafið að nýju við Þorbjörn á Reykjanesi. (17.3.2020) Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 " Veðurstofa Íslands:Vísbendingar um nýtt kvikuinnskot á Reykjanesi. (2.4.2020) Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Veðurstofa Íslands: Átta þúsund skjálftar síðan í lok janúar á Reykjanesskaganum. (10.4.2020) Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Thor Thordarson, Armann Hoskuldsson: Iceland. Classic geology of Europe 3. Harpenden 2002, pp. 64-65