| Legalism | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

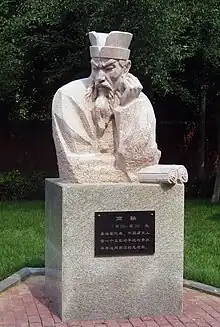

Statue of pivotal reformer Shang Yang | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 法家 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | School of Standards/Methods School of Law [1]: 59 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese legalism |

|---|

|

Fajia,[2] often termed Legalism is one of Sima Qian's six classical schools of thought in Chinese philosophy. Compared in the West with political realism and even the model-building of Max Weber,[3] the "Fa school of thought" represents several branches of what Feng Youlan called "men of methods",[4] who contributed greatly to the construction of the bureaucratic Chinese empire. Although lacking a recognized founder, the earliest persona of the Fajia may be considered Guan Zhong (720–645 BCE), while Chinese historians commonly regard Li Kui (455–395 BCE) as the first Legalist philosopher. The term Fajia was identified by Sinologist Herrlee G. Creel as referring to a combination of Shen Buhai (400–337 BCE) and Shang Yang (390–338 BCE) as its founding branches.

Sinologist Jacques Gernet considered the "theorists of the state" later christened fajia or "Legalists", to be the most important intellectual tradition of the fourth and third centuries BCE.[5] With the Han dynasty taking over the governmental institutions of the Qin dynasty almost unchanged, the Qin to Tang dynasty were characterized by the "centralizing, statist tendencies" of the Fa tradition. Leon Vandermeersch and Vitaly Rubin would assert not a single state measure throughout Chinese history as having been without Legalist influence.[6]

Dubbed by A. C. Graham the "great synthesizer of 'Legalism'", Han Fei is regarded as their finest writer, if not the greatest statesman in Chinese history (Hu Shi). Often considered the "culminating" or "greatest" of the Legalist texts,[7] the Han Feizi is believed to contain the first commentaries on the Dao De Jing. Sun Tzu's Art of War incorporates both a Daoist philosophy of inaction and impartiality, and a Legalist system of punishment and rewards, recalling Han Fei's use of the concepts of power (勢, shì) and technique (術, shù).[8] Temporarily coming to overt power as an ideology with the ascension of the Qin dynasty,[9]: 82 the First Emperor of Qin and succeeding emperors often followed the template set by Han Fei.[10]

Though the origins of the Chinese administrative system cannot be traced to any one person, prime minister Shen Buhai may have had more influence than any other in the construction of the merit system, and might be considered its founder, if not valuable as a rare pre-modern example of abstract theory of administration. Creel saw in Shen Buhai the "seeds of the civil service examination", and perhaps the first political scientist.[11][12]: 94

Concerned largely with administrative and sociopolitical innovation, Shang Yang was a leading reformer of his time.[13][9]: 83 His numerous reforms transformed the peripheral Qin state into a militarily powerful and strongly centralized kingdom. Much of Legalism was "the development of certain ideas" that lay behind his reforms, helping lead Qin to ultimate conquest of the other states of China in 221 BCE.[14][15]

Taken as "progressive," the Fajia were "rehabilitated" in the twentieth century, with reformers regarding it as a precedent for their opposition to conservative Confucian forces and religion.[16]

Historical background

The Zhou dynasty was divided between the masses and the hereditary noblemen. The latter were placed to obtain office and political power, owing allegiance to the local prince, who owed allegiance to the Son of Heaven.[17] The dynasty operated according to the principles of Li and punishment. The former was applied only to aristocrats, the latter only to commoners.[18]

The earliest Zhou kings kept a firm personal hand on the government, depending on their personal capacities, personal relations between ruler and minister, and upon military might. The technique of centralized government being so little developed, they deputed authority to regional lords, almost exclusively clansmen. When the Zhou kings could no longer grant new fiefs, their power began to decline, vassals began to identify with their own regions. Aristocratic sub-lineages became very important, by virtue of their ancestral prestige wielding great power and proving a divisive force. The political structures late Springs-and-Autumns period (770–453 BCE) progressively disintegrated, with schismatic hostility and "debilitating struggles among rival polities."[19]

In the Spring and Autumn period, rulers began to directly appoint state officials to provide advice and management, leading to the decline of inherited privileges and bringing fundamental structural transformations as a result of what may be termed "social engineering from above".[1]: 59 Most Warring States period thinkers tried to accommodate a "changing with the times" paradigm, and each of the schools of thought sought to provide an answer for the attainment of sociopolitical stability.[13]

Confucianism, commonly considered to be China's ruling ethos, was articulated in opposition to the establishment of legal codes, the earliest of which were inscribed on bronze vessels in the sixth century BCE.[20] For the Confucians, the Classics provided the preconditions for knowledge.[21] Orthodox Confucians tended to consider organizational details beneath both minister and ruler, leaving such matters to underlings,[12]: 107 and furthermore wanted ministers to control or at least admonish the ruler.[22]: 359

Concerned with "goodness", the Confucians became the most prominent, followed by proto-Daoists and the administrative thought that Sima Tan termed the Fajia. But the Daoists focused on the development of inner powers, with little respect for mundane authority[23][24] and both the Daoists and Confucians held a regressive view of history, that the age was a decline from the era of the Zhou kings.[25]

Mohism and fa

The Mohists, of Mozi (c. 470 BC – c. 391 BC), a school of political-religious engineers and logicians, are of particular importance to understanding Fa, meaning "to model on" or "to emulate". Compared by Fraser of the Stanford Encyclopedia with Socrates, the hermeneutics of the Mohists contained the philosophical germs of what Sima Tan would term the "Fa-School", initiating philosophical debate in China, positing some of its first theories, and contributing to the political thought of contemporary reformers.

Finding the values of tradition and Confucian li (ritual) unconvincing, they took universal welfare and the elimination of harm as morally right. Arguing against nepotism, they argued in favor of objective standards (fa) to unify moral judgements. Advocating thrift over extravagance, the Mohist's social goals included economic wealth, population growth, and social order.

Taking social order as a paramount, universally assumed good, the Mohists advocated a unified, peaceful, utilitarian or consequentialists ethical and political order, with an authoritarian, centralized meritocratic state, led by a virtuous, benevolent sovereign. To this end, their austere, disciplined groups were devoted to education, training, advocacy, government and sometimes, generally defensive military service.

Mozi used fa in the sense of models and standards for copy and imitation in action. As in Confucianism, Mozi's ruler is intended to act as the fa (or example) for the nobles and officials, as developing towards political technique. Although Confucianism does not much elaborate on fa, it would be illustrated in the Confucian canon using the idea of a circle as standard or identifier for other circles, adopting fa as a standpoint for administrative appointment.

Illustrated by the scale, grain-leveler and ink and line, together with a benevolent heart, Mencius's ruler will not achieve effective results without fa. As a figure between contemporaries Shang Yang/Shen Buhai and Han Fei, Mencius's fa more broadly represents models, exemplars and names. Amongst other categories, as including techniques of the heart-mind, Mencius's fa includes more specific examples of statistics such as temperatures, volumes, consistencies, weights, sizes, densities, distances, and quantities. Xun Kuang's notion of fa arguably derives from Confucian li as applied to the regulation of human behavior.[26]

The elimination of harm

Although Han Fei advocates Shang Yang's penal law, post-Graham (1989) Sinology does not appear to differentiate the Fajia primarily by punishment. As Sinologist Hansen notes, both Mohist and later Confucian (Xun Kuang) philosophy have punishment.

Following the Cambridge History, Hansen reiterated fa as representing comparative method with objective standards. Fa in the Qin empire is not primarily connected to punishment. Fa is primarily connected with administration. Although Han Fei advocates punishment in his time, Sinologist Makeham did not regard punishment as a primary or even necessary component of Han Fei's comparative Xing-Ming, or administrative method.

Rather, although in retrospect punishment may not be the most effective method sociologically, Shang Yang and Han Fei repeatedly advocate abolishing punishment with punishment, which is regarded as one tool. Although regarding it as a digression of minor importance, Pine's notes The Book of Lord Shang as allowing for the possibility that a need for "excessive reliance on coercion would end, and a milder, morality-driven political structure would evolve."

Although the Book of Lord Shang has been regarded as profoundly anti-people, as apart from it's larger program of agriculture and war, it also advocates spreading of penal knowledge in-order to prevent arbitrary punishment by ministers, who are punished for it's abuses by the self-same law. Although Hansen was not fond of Han Fei, he did not regard him as anti-people. Pine's Stanford Encyclopedia modernly reiterates fa as a principle of transparency rather than oppression.

Based on the archaeology in the Cambridge history, by the time of the Qin empire, the Qin had reduced punishment, as noted by Pines modernly. Primarily representing banishment to the colonies, it was otherwise deferred into fines. Even when the fine could not be paid the punishment was not executed, because they could then work for the government.[27]

School of names

The School of Names (Xingmingjia) was a school of Chinese philosophy that grew out of Mohism during the Warring States period in 479–221 BCE. Warring States era philosophers Deng Xi, Yin Wen, Hui Shi, Gongsun Long were all associated with the School of Names, as developing out of the Mohists. A contemporary of Confucius and the younger Mozi, Deng Xi (died 501 BC) is reported to have drawn up a code of penal laws, and is cited by Liu Xiang as the originator of principle of the xíngmíng (刑名), or ensuring that ministers' deeds (xing) harmonized with their words (ming).[28] Many in the school of names, slurred as disputers even in the Warring States period, would also have been administrators, just as the Mohists more broadly had sought office.

Often having been taken in the west as simply amoral, Chinese scholar Peng He positively associates Deng Xi with Chinese Legalism, which she defends in connection with the Chinese legal tradition. The primary categorical difference is that the Fajia or Legalists, initially employed as a Han dynasty slur, are a posthumous category invented by Sima Qian, who does not name anyone under the schools. Originally classed xingming, Shen Buhai and Han Fei are named Fajia in the Hanshu. Shen Buhai uses early the School of Names Ming-shi, or word and substance, while Han Fei uses Xing-Ming. However, as pioneering figures, they do have theoretical advancements and distinctions that have been asserted as to call them more 'Legalist'.[29]

Although the Hanshu would not be without contemporary gloss, with the office designations a posthumous invention, as with the Fajia, the school of names receive a similarly mixed posthumous reception:

The tradition of the Mingjia probably derives from the Office of Rites. In antiquity titles (ming) and ranks were not the same, and the rites also differed in their regulations. Confucius said: "It is necessary that words(ming) be rectified! If words are not rectified, then speech will not be in order. If speech is not in order, then state projects will not be completed. This is the Mingjia strength. But when it is employed for over fine distinctions, then it is only destructive and divisive."

Gongsun Long wrote the discourse "Hard and White." It splits words and dissects phrases in the service of twisty words. It adds nothing to dao-principles, it is without benefit to governance. Wang Chong (c.e. 27-ca.100)

Administrator Shen Buhai, as Prime Minister of the Hann state, is not known for penal law, and disadvises punishment. For the purposes of personnel selection and performance control, Shen makes use of the school of names method of ming-shi, meaning name and reality, or word and substance. In other words, Shen Buhai compares minister's words with their "substance", being the result of their proposal.

Whether himself much associated among their league or not, the importance of words and names to the period cannot be overstated, let alone for administration. Logician Gongsun Long similarly enjoyed the support of rulers, while Hui Shi, like Shen Buhai, was a prime minister in the state of Wei. One might think Gongsun Long's white horse paradox semantical, but Su Qin (380–284 BCE) considered it a component of Xingming administrative strategy. Although Han Fei is at times antagonistic towards language devices, a white horse strategy is found in the later chapters Han Feizi, along with other similar strategies:[30]

Once Tzu-chih, Premier of Yen, while seated indoors, asked deceptively, "What was it that just ran outdoors? A white horse?" All his attendants said they had seen nothing running outdoors. Meanwhile, someone ran out after it and came back with the report that there had been white horse. Thereby Tzu-chih came to know the insincerity and unfaithfulness of the attendant.

Once there were litigants. Tzu-ch'an separated them and never allowed them to speak to each other. Then he inverted their words and told each the other's arguments and thereby found the vital facts involved in the case.

Canon VII.

Shen Buhai is similarly "paradoxical" in the sense that even ordinary ancient Chinese considered him mysterious, being difficult to translate even in Sinologist Creel's time. As Creel says however, he was not necessarily difficult to understand by those who knew the lingo, being originally written for those intended to read it. As a figure lacking in both punishment and standardized law, the main reason Shen Buhai would initially be taken into the Fajia, rather than the school of names, is because he is slurred together with Shang Yang in the Han Feizi. Creel considered, at basic, the Han Feizi largely similar to the Shen Buhai fragments. Reportedly receiving the Han Feizi, the stele of the First Emperor list Xingming amongst his accomplishments.

Characterization

Hansen differentiated Han Fei from earlier analytical philosophy as being in part opposed to it, with their fa more generally suiting the ruling purpose. John Makeham characterized earlier school of names thinkers as more resembling the Confucian rectification of names, taking Xun Kuang's Xing-Ming as second phase, and Han Fei's Xing-Ming or administrative method it's third. Makeham differentiates Han Fei's method from his school of names predecessors as representing an unprecedented mechanical advancement.

Although regarding Shen Buhai as an originator, if not the major originator of the 'Legalist' doctrine of names, Makeham has less to say on him. Sinologist Goldin does regard the Xing-Ming idea earlier originating in Shen Buhai, matching an official's performance to his office, as requiring any legal consciousness whatsoever. Lü Peng modernly criticizes Shen Buhai's craft in particular as not contributing to the formation of consistent rules, with each subject having their own 'legal basis'. Tao Jiang recalls Creel as backing for Shen Buhai's pedigree, with his retrospective success, despite vilification, based in part on lacking punishment.

With an aim to encourage it's subject, Tao Jiang in particular defends the Fajia as a posthumous category, following Creel in distinguishing Legalism from it. Earlier held by Creel and Graham, adding Korean scholar Soon-Ja yang, Tao Jiang re-asserts it's members as focused on fa. Works taking simple power as primary tend to predate the century. Works taking Shen Dao's secondary philosophy of shih or situational authority as primary serve as Daoist explorations.

Given its own section as Graham's realism, Tao Jiang recalls the Fajia's members as "appropriately placed" in taking the state and people "as they actually are" rather than an ideal vision, with other early thinkers taking politics as ethical. He characterizes them under a Grahamistic scrutinization of personal virtues as connected with political authority. He takes their singular focus to be the institutionalization of political power at the expense of the ruler's involvement. Sinologist Pines has even regarded them as attempting to subjugate the ruler to laws and methods. Most other early philosophers not separating the two, the fajia consider personal virtues disruptive or even hostile towards political power.

Although the Han dynasty may not have received Shang Yang as a bureaucratic organizer, Tao Jian legitimates Shang Yang and Shen Buhai as pioneers in the bureaucratization of the state, in its highest positions, at "the beginning of a top-down political revolution", transforming subsequent Chinese political history. Creel took the civil service examination and systematic rating of officials as dating back to Shen Buhai, attributing Shen Buhai's success to being less draconian than Shang Yang.

Pines Stanford Encyclopedia, or fa Tradition, takes them as political realists who sought rich states and powerful armies in their time, as in particular a Shang Yang to Han Fei line, but openly follows Creel's Shen Pu-Phai in taking a proper staffing and monitoring of the bureaucracy to be their lasting contribution. Although administration tends not to be concerned with morality, Pines qualifies the tradition as moral "insofar as morality is represented by the principle of impartiality rather than by Confucian insistence on 'benevolence and righteousness'".[31]

Creel's branches of the Fajia

Recalled by Tao Jiang, Creel (and more modernly Kidder Smith) take Han Fei as at least inadvertently responsible for the ultimate association of Shang Yang and Shen Buhai together in the Fajia, leading to a categorical confusion between them and Legalism. With the terms in Sinological disrepute, Tao Jiang reasserts Creel's acceptance of Shang Yang as ancient China's Legalist school.[32] Credited by Sinologist Herrlee G. Creel as syncretic precedent for their association within the Fajia, and with its lense reiterated by K.C. Hsiao, Michael Loewe, A.C. Graham, and S.Y. Hsieh, Chapter 43 of the Han Feizi says:

Now Shen Buhai spoke about the need of Shu ("Technique") and Shang Yang practices the use of Fa (law or more broadly "Standards"). What is called Shu is to create posts according to responsibilities, hold actual services accountable according to official titles, exercise the power over life and death, and examine into the abilities of all his ministers; these are the things that the ruler keeps in his own hand. Fa includes mandates and ordinances promulgated to the government offices, penalties that are definite in the mind of the people, rewards that are due to the careful observers of standards, and punishments that are inflicted upon those who violate orders. It is what the subjects and ministers take as a model. If the ruler is without Shu he will be overshadowed; if the subjects and ministers lack Fa they will be insubordinate. Thus, neither can be dispensed with: both are implements of emperors and kings.

Associated with penal law in the Han dynasty, but never bureaucratic organization, Gongsun's administration may be associated more broadly with agriculture and war. Shen Buhai is associated with bureaucratic organization, but never penal law prior Han Dynasty gloss. Appointed following the collapse of the Jin state, Shen Buhai issued regulations or laws, but did so haphazardly, without repealing the older ones. Hence, in contrasted gloss to Gongsun Yang, he "lacks fa."

Shu, or method/technique, as the most frequently used term to describe Shen Buhai's doctrine historically, does not appear in the Shen Buhai fragments. Only shu numbers does, which Creel took as evolving towards technique. Han Fei and Li Si (the latter as quoted by Sima Qian) quote Shen Buhai as using fa in the sense of what Creel translated as method, but never law. While Han Fei has tactics in later chapters, method itself is concerned almost exclusively with the ruler's selection of ministers, as including performance monitoring.

Shang Yang primarily uses fa as law, but fa sometimes means both law and method even in the Shangjunshu. As example in brief, along with a good nature, the fa (method and law) of the sage compels the faith of the empire. While representative of his opposite branch, fa-shu or method-technique appears even in the Shangjunshu. Following Creel, A.C. Graham takes Han Fei's shu as "distinguishing between law as public and method as private", sharpened by the contrast between the two, calling method the arcanum of the ruler.

Goldin reiterates: Han Fei glosses Shen Buhai under his own doctrine of shu, which includes reward and punishment, with Shen Buhai as lacking fa. Shen Buhai uses fa quite often. But there is another figure who has administration with reward and punishment: the philosopher Shen Dao. Although Shen Dao and Han Fei make some usage of fa as akin to law, with reward and punishment, the three all generally use fa in much the same sense as Shen Buhai, that is, as an impersonal administrative technique. With a particular quotation from Han Fei as example:

An enlightened ruler employs fa to pick his men; he does not select them himself. He employs fa to weigh their merit; he does not fathom it himself. Ability cannot be obscured nor failure prettified. If those who are [falsely] glorified cannot advance, and likewise those who are maligned cannot be set back, then there will be clear distinctions between lord and subject, and order will be easily [attained]. Thus the ruler can only use fa.

Goldin's (2011) Persistent Misconceptions mainly reiterated Creel's objection to the term Legalism, questioning a glossing of the primarily bureaucratic Han Fei with Shang Yang. In contrast to Shang Yang, who himself addresses statutes and other questions from an administrative standpoint, they primarily use fa more administratively. Taking Goldin as antagonist in a rejection of the Fajia and Legalism as categories, Tao Jiang employs Goldin as illustration that they are fa theorists, as opposed to shu or shi theorists, as a view from Han Fei's standpoint dating back Feng Youlan (1948). Although Goldin does not espouse it, it had been contemporary.

Represented in chapter 40 of the Han Feizi, the scholar Shen Dao covered a "remarkable" quantity of 'Legalist' and Daoist themes. Lacking a recognizable group of followers, with clearly Daoistic usages and representation in the Zhuangzi, he would be accepted as a relevant philosophical forebear for the Daoists. Although focused on fa, he was remembered for shih because he is mentioned the Han Feizi for his themes on shi as "power" or more namely "situational advantage", for which he is also incorporated into The Art of War. Despite shih's necessity, and although seeking to improve its argument, Han Fei says that he speaks on shi "for mediocre rulers", emphasizing institution. Korean scholar Soon Ja Yang notes the term as only appearing twice in the Shen Dao fragments. Xun Kuang calls him "beclouded with fa", associating fa primarily with Shen Dao, naming Shen Buhai for the doctrine of position (shi).[33] [34]

Shang Yang

Hailing from Wei, as Prime Minister of the State of Qin, Shang Yang (390–338 BCE) engaged in a "comprehensive plan to eliminate the hereditary aristocracy". Drawing boundaries between private factions and the central, royal state, he took up the cause of meritocratic appointment, stating "Favoring one's relatives is tantamount to using self-interest as one's way, whereas that which is equal and just prevents selfishness from proceeding."

As the first of his accomplishments, historiographer Sima Qian accounts Shang Yang as having divided the populace into groups of five and ten, instituting a system of mutual responsibility tying status entirely to service to the state. It rewarded office and rank for martial exploits, going as far as to organize women's militias for siege defense.

The second accomplishment listed is forcing the populace to attend solely to agriculture (or women cloth production, including a possible sewing draft) and recruiting labour from other states. He abolished the old fixed landholding system (fengjian) and direct primogeniture, making it possible for the people to buy and sell (usufruct) farmland, thereby encouraging the peasants of other states to come to Qin. The recommendation that farmers be allowed to buy office with grain was apparently only implemented much later, the first clear-cut instance in 243 BCE. Infanticide was prohibited.

Shang Yang deliberately produced equality of conditions amongst the ruled, a tight control of the economy, and encouraged total loyalty to the state, including censorship and reward for denunciation. Law as such was what the sovereign commanded, and this meant absolutism, but it was an absolutism of Fa (administrative standards) as impartial and impersonal, which Gongsun discouraged arbitrary tyranny or terror as destroying.

Emphasizing knowledge of the Fa among the people, he proposed an elaborate system for its distribution to allow them to hold ministers to it. He considered it the most important device for upholding the power of the state. Insisting that it be made known and applied equally to all, he posted it on pillars erected in the new capital. In 350, along with the creation of the new capital, a portion of Qin was divided into thirty-one counties, each "administered by a (presumably centrally appointed) magistrate". This was a "significant move toward centralizing Ch'in administrative power" and correspondingly reduced the power of hereditary landholders.

Shang Yang considered the sovereign to be a culmination in historical evolution, representing the interests of state, subject and stability.[35] Objectivity was a primary goal for him, wanting to be rid as much as possible of the subjective element in public affairs. The greatest good was order. History meant that feeling was now replaced by rational thought, and private considerations by public, accompanied by properties, prohibitions and restraints. In order to have prohibitions, it is necessary to have executioners, hence officials, and a supreme ruler. Virtuous men are replaced by qualified officials, objectively measured by Fa. The ruler should rely neither on his nor his officials' deliberations, but on the clarification of Fa. Everything should be done by Fa,[9]: 88 whose transparent system of standards will prevent any opportunities for corruption or abuse. [36][37]

Enlightened Absolutism

Lacking an organized code or penal law, Shen Buhai advised that the ruler at least keep control over the powers of life and death, rather than delegate them to the ministers. Hiding the ruler's weaknesses, Shen Buhai's ruler makes use of method (fa) in secrecy, aiming for a complete independence that challenges "one of the oldest and most sacred tenets of Confucianism"; that of respectfully receiving and following ministerial advice.

Recalled by Tao Jiang, Creel marvels at the degree of Shen Buhai's emancipation from considerations of religion, tradition, familial ties, or loyalty, basing governmental thought almost entirely upon administrative technique and applied psychology. Although Shen Buhai considers the ministers one of the ruler's greatest dangers, he did not advocate that the ruler should suppress ministers, but seek their cooperation.

At basic a fa impartialist, Shen Buhai advocates an impartial point of view. In that sense, he does not simply consider them potential enemies. Although Han Fei's Shu technique is nonsensical without fa objective standards, and therefore also fitting its category, Tao Jiang contrasts Shen Buhai fa with Han Fei's Shu as more impartial.

Xuezhi Guo's Ideal Chinese Political Leader contrasts the Confucian "Humane ruler" with the 'Legalists' as "intending to create a truly 'enlightened ruler'". He quotes Benjamin I. Schwartz as describing the features of a truly Legalist "enlightened ruler":[104]

He must be anything but an arbitrary despot if one means by a despot a tyrant who follows all his impulses, whims and passions. Once the systems which maintain the entire structure are in place, he must not interfere with their operation. He may use the entire system as a means to the achievement of his national and international ambitions, but to do so he must not disrupt its impersonal workings. He must at all times be able to maintain an iron wall between his private life and public role. Concubines, friends, flatterers and charismatic saints must have no influence whatsoever on the course of policy, and he must never relax his suspicions of the motives of those who surround him.

As easily as mediocre carpenters can draw circles by employing a compass, anyone can employ the system Han Fei envisions.[38] The enlightened ruler restricts his desires and refrains from displays of personal ability or input in policy. Capability is not dismissed, but the ability to use talent will allow the ruler greater power if he can utilize others with the given expertise.[39] Laws and regulations allow him to utilize his power to the utmost. Adhering unwaveringly to legal and institutional arrangements, the average monarch is numinous.[40][41] A.C. Graham writes:

[Han Fei's] ruler, empty of thoughts, desires, partialities of his own, concerned with nothing in the situation but the 'facts', selects his ministers by objectively comparing their abilities with the demands of the offices. Inactive, doing nothing, he awaits their proposals, compares the project with the results, and rewards or punishes. His own knowledge, ability, moral worth, warrior spirit, such as they may be, are wholly irrelevant; he simply performs his function in the impersonal mechanism of the state.[42]: 288

Resting empty, the ruler simply checks "shapes" against "names" and dispenses rewards and punishments accordingly, concretizing the Dao or way standards for right and wrong. Submerged by the system he supposedly runs, the alleged despot disappears from the scene.[43]

Anti-ministerialism

Although less antagonistic than Han Fei, Shen Buhai still believed that the ruler's most able ministers are his greatest danger, and is convinced that it is impossible to make them loyal without techniques. Shen Buhai argued that if the government were organized and supervised relying on proper method (fa), the ruler need do little – and must do little, putting up a front to hide his dependence on his advisors. Well aware of the possibility of the loss of the ruler's position, and thus state or life, from said officials, Shen Buhai says:

One who murders the ruler and takes his state ... does not necessarily climb over difficult walls or batter in barred doors or gates. He may be one of the ruler's own ministers, gradually limiting what the ruler sees, restricting what he hears, getting control of his government and taking over his power to command, possessing the people and seizing the state.

Prince Han Fei includes Shen Buhai under his own doctrine of Shu administrative technique, as including Xing-Ming, or form and name, alongside the power over life and death. His Xing-Ming names (ming) ministers to office, comparing ministerial proposals (ming) with results (Xing, form) for appointment and performance monitoring. Han Fei addends Shang Yang's automatic reward and punishment to the method.

Han Fei's 'brilliant ruler' "orders names to name themselves and affairs to settle themselves."[44]

"If the ruler wishes to bring an end to treachery then he examines into the congruence of the congruence of xing (form, or result of the proposal) and claim (ming). This means to ascertain if words differ from the job. A minister sets forth his words and on the basis of his words the ruler assigns him a job. Then the ruler holds the minister accountable for the achievement which is based solely on his job. If the achievement fits his job, and the job fits his words, then he is rewarded. If the achievement does not fit his jobs and the job does not fit his words, then he will be punished

Han Fei presents Qin reformer Shang Yang, known for penal law with harsh punishments, as the opposite component of his doctrine. That being said, Han Fei does not seek to simply implement Shang Yang's laws or policies. Considering the officials bent on usurping the throne, Han Fei uncompromisingly opposes a subversion of the law to the detriment of the people and state, famously criticizing Shang Yang for paying insufficient attention to governing the political apparatus. With shu aiming to limit the ministers power relative to the ruler, the publicly named fa of Shang Yang limits their power over the people, punishing ministers who abuse the law with the given law. Tao Jiang quotes:[45]

Judging from the tales handed down from high antiquity and the incidents recorded in the Spring and Autumn Annals, those men who violated the laws, committed treason, and carried out major acts of evil always worked through some eminent and highly placed minister. And yet the laws and regulations are customarily designed to prevent evil among the humble and lowly people, and it is upon them alone that penalties and punishments fall. Hence the common people lose hope and are left with no place to air their grievances. Meanwhile the high ministers band together and work as one man to cloud the vision of the ruler. (Watson trans. 2003, 89)

The 12 characters on this slab of floor brick affirm that it is an auspicious moment for the First Emperor to ascend the throne, as the country is united and no men will be dying along the road.

Sima Qian's Fajia

Probably never a school, organized or self-aware movement, the Fa-school or Fajia would only be considered a school starting in the Han dynasty, with Sima Tan and Sima Qian essentially inventing the Fajia in the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji). Sima Tan does not name anyone under the schools.

The figures would only be assembled and slurred as Fajia "Legalists" one hundred years after him, in the Hanshu, or Han History. The Han History lists Li Kui, Shang Yang, Shen Buhai, Han Fei, Shen Dao, and Han Fei under the School of Fa (Fajia). While Li Kui is a predecessor of Shang Yang in their native state of Wei, the figures listed are otherwise those of the Han Feizi, as purportedly received by the first emperor.

Although dated, to paraphrase A.C. Graham:

Han Fei sees Lord Shang's thought as centred on law (fa) but Shen Buhai on 'methods' (fa-shu), techniques for controlling administrators. He himself declares law and method both indispensable. Elsewhere he mentions Shen Dao as giving central importance to shi (situation authority), which some took as evidence of a third tendency. However, fa is prominent in the Shen Dao fragments.

Occasionally used conventionally, Kidder Smith (2003) takes the terms Legalism and Fajia as having been in Sinological disrepute by his time. As presented by Creel, the Fajia would be utilized as a Han dynasty slur, combining administrator Shen Buhai, who disadvises punishment, with harsh Legalist Shang Yang, as the opposite component of Han Fei's doctrine. Shang Yang's public law punishes abuse by ministers. The slur was used to combat reform and ministerial management, despite early Han reformers, following the more administrative branch, often either not advocating harsh punishment, or advocating against it.

As for the Fajia, Sima Qian says:

The fajia are strict and have little kindness, but their alignment of the divisions between lord and subject, superior and inferior, cannot be improved upon. … Fajia do not distinguish between kin and stranger or differentiate between noble and base; all are judged as one by their fa. Thus they sunder the kindnesses of treating one’s kin as kin and honoring the honorable. It is a policy that could be practiced for a time, but not applied for long; thus I say: “they are strict and have little kindness.” But as for honoring rulers and derogating subjects, and clarifying social divisions and offices so that no one is able to overstep them—none of the Hundred Schools could improve upon this.

Even the early scholarship of Feng Youlan (1948) considered it incorrect to associate the thinkers with jurisprudence, describing them as teaching methods of organization and leadership for the governing of large areas. However, with Shen Buhai less remembered, and only translated by Creel in 1974, Science and Civilization in China (1956) took the "central conception" of fa as positive law expounded with "great clarity by Gongsun Yang in the Shangjunshu". Sinologist Creel saw Legalism to "contrast strangely" with Han Fei blaming Shen Buhai, as the opposite of his doctrine from Shang Yang, for concentrating all of his attention on administrative technique and neglecting law.

Because, historically, despite the presentation of their opponents, those advocating policies derived of Shang Yang or Shen Buhai did not endorse each other's views, Creel advised that the Shen Buhai group be called "administrators", "methodists" or "technocrats", in contrast to the more "Legalist" Shang Yang. Seeing remarkable similarities between Shen Buhai and the Han Feizi, noting imperial China as never fully accepting the role of law and jurisprudence, taking the managerial Shen Buhai branch as predominantly influential, and seeing the Shangjunshu as also sometimes using fa administratively, Creel opined that Legalists did not play a great role in the formation of traditional Chinese government. Promoted modernly as a bureaucratic pioneer by Tao Jiang, Shang Yang played a role in contemporary reform, but as Yuri Pines notes in the Stanford Encyclopedia, Shang Yang's heavy punishments and agricultural focus for instance had been earlier abandoned by the Qin.

With the archaeological discoveries represented in the Cambridge History, the Qin empire's laws were primarily administrative, concerned with such items as weights and measures. Fa itself primary refers to such items as mdoels, standards, norms and patterns. Only derivatively including penal law as adjunct to li ritual, fa as comparative model manuals in the Qin empire guided penal legal procedure and application based on real life situations, with publicly named wrongs geared to punishments. Banishment a normal punishment under the Qin empire, with exiles sent to the newly conquered regions. Redemption of punishment however was common, and frequently allowed up to even the death penalty. Even in cases where the condemned person was unable to pay the fee, the punishment was not executed, because then he was made to repay his obligation by working for the government. More generally, punishment could be redeemed by relinquishing an order or orders of aristocratic ranks.

Jingyuan Ma and Mel Marquis in Confucian Culture and Competition Law in East Asia consider the Qin's code to have primarily been penal, but they reference sources older than the Cambridge.[46]

The Han empire would be consolidated by the somewhat more Legalist Gongsun Hong and Zhang Tang, combating Sima Qian's aristocratic Huang-Lao faction. Although less accurate for Shang Yang, Sima Qian originally glosses Shang Yang, Shen Buhai and Han Fei as Xing-Ming, as referring to the School of Names and their administrative method. With an aim to revive its little-discussed subject, although himself using Fajia, Tao Jiang (2021) recalls Creel as differentiating Legalism from the Fajia, with Shang Yang as ancient China's Legalist school. With reference to an older critique in Sinologist Goldin, the Stanford Encyclopedia modernly terms them the fa Tradition, although still accepting Legalism as having explorative value.[47]

Han Dynasty slurring

Although Han Fei, in the Warring States period, advocates harsh punishment, Emperor Wen of Han is noted for reducing punishments and making capital punishment rare. He is regarded by the Shiji and Hanshu as basically fond of Xing-Ming. While Sima Qian's own Huang-Lao faction, favoring the feudal lords, uses Xing-Ming, Sima Qian adds Shang Yang to Xing-Ming in the Records, glossing together Shang Yang, Shen Buhai and Han Fei as followers of the doctrine of Xing-Ming. Not being a bureaucratic organizer, Shang Yang is not known for Xing-Ming, but glossing often occurred in Chinese texts. Their later grouping under the Fajia aside, it would serve as secondary historical moniker for the figures.

Pairing Shang Yang and Shen Buhai, Sima Qian names reformers like Jia Yi as an advocate of Shen Buhai and Shang Yang in the records. Advocating for reform, although a past student of the Qin dynasty official Li Si, Jia Yi wrote the Disquisition Finding Fault with the Qin, and as Sinologist Creel notes was probably not an advocate of Shang Yang. Moreover, centered on agriculture and war, Shang Yang's exclusivist preoccupation with agriculture had been abandoned by the Qin, and his punishments reduced.

With the encouragement of Emperor Wen, Jia Yi drew up "complete plans for revising the institutions of government and reorganizing the bureaucracy", which Emperor Wen put into effect. Exiled by Emperor Wen under factional pressures to the southern Changsha Kingdom, Jia Yi was sent to tutor one of Wen's sons, Liu Yi/Prince Huai of Liang. With the Han dynasty shifting favor from Huang-Lao to Confucianism, the orthodox interpretation of the fajia becomes Confucian and more critical. It would "be quite popular and respectable to oppose the harsh use of penal law", and apart from disliking the managerial controls of xingming itself, those otherwise disliked by the Confucian orthodoxy, with some philosophical association, would also often be slurred as fajia, like the otherwise Confucianistic reformers Guan Zhong and Xunzi, and Sima Qian's own Huang-Lao faction.

Over the Han dynasty, Xing-Ming would sometimes be used in reference to Han Fei and Shang Yang, rather than Shen Buhai and Han Fei, the school of names, or their technique. Although Sima Qian appeared to be aware of the differences between Shen Buhai and Shang Yang, Creel suggests that this would seem to disappear among scholars as early as the Western Han dynasty. Xing (form/results) would be glossed as punishment in the later part of the Han dynasty, coming to encompass the prohibitionist texts, or penal law, down to the fall of the Qing dynasty. Its meaning would be so completely lost that Duvendak, 1928 translator for the Book of Lord Shang, would translate Xing as criminal law.

The historiographer Liu Xin (c. 50 BCE – 23 CE), as a kind of follow up work, assigned the schools as having originated in various ancient departments, portraying the Fajia as having originated in what Feng Youlan translates as the Ministry of Justice, emphasizing strictness, reward and punishment. Its view would be adopted by later Chinese scholars even into the later 1700s. The Western Jin Hanshu commentator Jin Zhuo separates Xing-Ming as xing-jia and ming-jia, with the latter as referring to the earlier school of names, under the retroactive idea of Xing-Ming as a contraction of the schools. The term Xing-Ming reappears in later dynasties, but for the uninitiated, Xing (result of the proposal) becomes punishment, criminal law, or "the school of punishments."[48]

Earlier classification as Huang-Lao

.jpg.webp)

Sima Qian originally claimed Shen Dao, Shen Buhai, and Han Fei as having studied the teachings of his own faction, "the Teachings of the Yellow Emperor and Lao-tzu" (Huang-Lao), synonymous with daojia ('school of Dao', early Daoism). Although modernly included under early Daoism, it would not have meant Daoism as understood modernly. With pre-Han Daoists also more an informal network than an organized school or movement, Daojia first appears in the Records, and is also taken as retrospective.

Regardless, texts commonly classed Guan Zhong and Shen Dao under Daojia before Fajia. Associated with the much earlier Guan Zhong, the Guanzi, with its proto-daoist texts, was classed as Daoist in the Han bibliography. The lack of distinction between Daojia and Fajia would not suggest that the distinction existed prior to the Han.

Given its precedent, with formal similarities between the texts and Daoism as including Han Fei's advocacy of wu wei (so-called "effortless action") or reduced activity by the ruler, the theorists were often supposed by the Chinese and early scholarship to have studied Daoism. Modern scholarship does not take the Daodejing to be as ancient. Incomplete versions date back to the fourth century B.C., while the earliest complete written editions of the Daodejing only date back to the early Han dynasty. No pre-Han records discuss it.

By Creel's time, few critical scholars believed Laozi to have been a contemporary of Confucius. Although incomplete versions of the Daodejing may have been contemporary to Shen Buhai's time, Creel did not find Shen Buhai, as Han Fei's predecessor and prior prime minister of their native Hann state, to be influenced by Daoist ideas, lacking metaphysical content. Shen Buhai quotes the Analects of Confucius, in which Wu Wei can also be seen as an idea.

As had generally already been accepted by scholarship at the time, Creel did not find the Han Feizi's Daodejing commentary to have been written by Han Fei. A.C. Graham would reiterate that Han Fei does not appear to make effective use of it. The Han Feizi is most similar to the Shen Buhai fragments. Evidences for Daoist influence on the Han Feizi remain lacking outside of a few tertiary chapters.

The final chapter of the Zhuangzi does not regard Laozi and Zhuangzi as having been part of a Daoist school. the Outer Zhuangzi's history includes Confucians, Mohists, Shendao, Laozi, and Zhuangzi, effectively leaving the Mohists as a primary influence. The Daodejing does not specifically suggest direct exposure to their subsequent school of names, although its discussion of "names that cannot be named" place it within the same milieu as a reaction to Mozi; Huang-Lao similarly bares its mark.

However, while others of the Fajia are left out, the Zhuangzi takes Shen Dao as Daoistic, preceding both Laozi and Zhuangzi. With precedent in Creel, Schwarz and Graham, Hansen of the Standford's Daoism would take Daoist theory as beginning in the relativist discussions of Shen Dao. He still considers Shen Dao's theory foundational for a Daoist favoring of Dao, as meaning guide, over Heaven, a narrative shared with the late Mohists in that an appeal to Heaven justifies thieves as well as sages.

Although modernly more often given to contrast and comparison with the Mohists, comparison and attempts to root the Han Feizi in proto-Daoist attitudes or naturalism can be still seen within scholarship. Creel did not exclude the possibility that Daoist ideas influenced the fajia before they were written down in the Zhuangzi and Daodejing, or for instance influence by Yang Zhu and the Yangists, but his evidences suggested Huang-Lao as not existing during Shen Buhai's time. Writing at the turn of its discussion, John Makeham (1990) still considered some of the Han Feizi's most typifying chapters as being of distinctly Daoist quality, not considering, at least, the dividing line between the two as having ever been particularly clear.[49] [50] [51]

Graham's Realism

Contrary to common comparisons of Han Fei with Machiavelli, Schwarz observed that Machiavelli taught an art rather than a science of politics, while the so-called Legalists "seem closer in spirit to certain 19th- and 20th-century social-scientific 'model builders'". Schwarz "finds in China more anticipations of contemporary Western social sciences than of the natural sciences", with Shen Buhai's 'model' of bureaucratic organization "much closer to Weber's modern ideal-type than to any notion of patrimonial bureaucracy."[52]

In the Realist vein, A.C. Graham's "Disputers of the Tao" titled his Legalist chapter "Legalism: an Amoral Science of Statecraft", sketching the fundamentals of an "amoral science" in Chinese thought largely, Goldin notes in a criticism, based on the Han Feizi, consisting of "adapting institutions to changing situations and overruling precedent where necessary; concentrating power in the hands of the ruler; and, above all, maintaining control of the factious bureaucracy."[42]: 267 [53]

Nonetheless, Eirik Lang Harris of The Shenzi Fragments (2016) echoes the view of "starting not from how society ought to be but how it is" as a commonality between the fajia's four most prominent figures. Although himself following a line of impartial justice for the Fajia, Tao Jiang's modern basic statement of formulation for the Fajia resembles Graham: With Fa as their key notion, the Fajia hold in common a focus in the institutionalization of political power, and a questioning of the moral values of the Confucians, disputing an assumed connection between personal virtue and political authority. Graham says: "they have common ground in the conviction that good government depends, not as Confucians and Mohists supposed on the moral worth of persons, but on the functioning of sound institutions."

Modernly, Yuri Pines of the Stanford's "fa tradition" still takes the realist principle as a foundation for the tradition. While Legalist interpretation has been criticized modernly, Pines takes Realism as having been defended to be more or less still legitimate, although as with Tao Jiang accepts Legalist interpretation as still having explorative value. Noting them as "generally devoid of overarching moral considerations", or conformity to divine will, Pines terms the members of the Fa tradition as "political realists who sought to attain a 'rich state and a powerful army' and ensure domestic stability", only displaying "considerable philosophical sophistication" when they needed to justify departures from conventional approaches.

Although taking the thinkers as realists, as a matter of discipline, Pines suggests the Fa tradition as a more suitable category, with fa itself representing not oppression but transparency. Pines qualifies against a perception of them as totalitarian, as stated by "not a few scholars", including Feng Youlan (1948), Creel (1953) as prior to some of his more prominent work on Shen Buhai, and Zhengyuan Fu's 1996 The Earliest Totalitarians. Although (the Shang Yang-Han Fei's branch's harsh laws or administrative rules) and "rigid control over the populace and the administrative apparatus" might seem to support totalitarianism, apart from exposing the fallacies of their opponents, the Fa tradition has little interest for instance in thought control, and Pines does not take them as "necessarily" providing an ideology of their own.[54][55]

Fajia and the fa tradition

Having prior used the popular term "Legalist", Pines (2023) of the Stanford Encyclopedia and translator for the Book of Lord Shang (2017), modernly characterizes them as the "fa tradition" and "fa thinkers". The term is shared by the as yet unpublished multi-authored work, the Dao Companion to China's Fa Tradition. As stated by their publisher, the Dao Companions aim to provide the most comprehensive and up-to-date introductions to various aspects of Chinese philosophy.

Tao Jiang (2021), un-cited by Pine's but taken as major achievement in his multi-authored review, Tao Jiang on the Fa Tradition, prior argued for the legitimacy of Fajia as a historical category with Fa in common between the thinkers. Pine's review lauds the work as "engaging the thinkers as theorists rather than mere statesmen, immersed in a dialog with earlier thinkers and texts." Pines shares the terminology of Thinker with Tao Jiang, but had already made prior use of it; Creel also called them "Fajia thinkers".

Pines connects Legalism to a common focus in earlier scholarship comparing the tradition to a modern rule of law, potentially undercutting its depth. Although taking law to be a correct translation for Fa in many contexts, Pines and Tao Jiang reiterate that it often refers to standards, models, norms, methods, regulations, or (as a verb) to follow. Simply translating it as law, Tao Jiang says, does not do justice to "how the term is used and what it encompasses in the texts involved."

Pines credits Goldin for a preference of the Fa tradition over Legalism, which he argued against as his essay's "most important obligation", saying that "Creel’s objection to translating fajia as 'legalism'" is "still valid today and deserves to be repeated"; even if one wishes to take Shang Yang, whose standpoint is administrative, as more Legalistic, Shen Buhai, who compares offices and performances, does not "presuppose a legal code or any legal consciousness whatsoever."

Goldin's critique of Fajia primarily considers it "partisan and anachronistic"; it was coined by Sima Tan to "urge his particular brand of syncretism as the most versatile world view for his time." While one might call oneself a Ru (Confucian), or pre-imperially a Mo (Mohists), no one ever actually called himself a Fajia, no Fa school actually existed, and no lineage actually existed. Pines considers it misleading as implying a self-aware, organized intellectual current commensurate with the followers of Confucius (551–479 BCE) or Mozi (c. 460–390 BCE), whereas no early thinker identified himself as a member of the Fajia, or 'school of fa'.

As opposed to this, Tao Jiang emphasizes their political prominence as unusual among classical thinkers, standing "at the beginning of a top-down political revolution that would radically transform the subsequent political history of China." Tao Jiang recalls Sinologist Ivanhoe, the fifth reference of the Oxford, who "defends the traditional Chinese use of jia to group classical thinkers by pointing out that jia (家) literally means 'family', whose intellectual families did not require relation by blood.

Although characterizing fa thinkers as political realists, as defended modernly to be more or less legitimate, Pines takes its usage as a designation to give the impression that "the opponents of fajia were mere idealists, which was not the case."[54][53][56][57]

Realist commentaries

In contrast to what he takes as the "simple behaviourism" of Schwarz and Graham, Sinologist Chad Hansen (1992) takes Han Fei as more sociological. The ruler should not trust people because their calculation is essentially based on their position, regardless of their past relationship. A wife, concubine or minister all have positional interests. Hence, the ruler engages in calculations of benefit rather than relation. Ministers simply interpret moral guidance in ways that benefit their position. The ruler exclusively uses Fa measurement standards for calculation to reduce possible interpretation. The enemy of order and control is simply the enemy of objective standards, draining power by twisting interpretation through consensus evaluation of clique interests.

Ross Terrill's 2003 New Chinese Empire viewed "Chinese Legalism" as "Western as Thomas Hobbes, as modern as Hu Jintao... It speaks the universal and timeless language of law and order. The past does not matter, state power is to be maximized, politics has nothing to do with morality, intellectual endeavour is suspect, violence is indispensable, and little is to be expected from the rank and file except an appreciation of force." He calls Legalism the "iron scaffolding of the Chinese Empire", but emphasizes the marriage between Legalism and Confucianism.

Leadership and management in China (2008) takes the writings of Han Fei as almost purely practical. With the proclaimed goal of a “rich state and powerful army”, they teach the ruler techniques (shu) to survive in a competitive world through administrative reform: strengthening the central government, increasing food production, enforcing military training, or replacing the aristocracy with a bureaucracy. Although typically associated with Shang Yang, Kwang-Kuo Wang takes the "enriching of the state and strengthening of the army" as dating back to Guan Zhong.

Contrary Graham, Goldin (2011) would not regard Han Fei as trying to work out anything like a general theory of the state, or as always dealing with statecraft. Noting Han Fei as also often concerned with saving one's hide, including that of the ruler, the Han Feizi also has one chapter offering advice to ministers "contrary to the interests of the ruler, although this is an exception... The fact that Han Fei endorses the calculated pursuit of self-interest, even if it means speaking disingenuously before the king, is not easily reconcilable with the reconcilable with the notion that he was advancing a science of statecraft."

Pines page has taken the goal of a “rich state with powerful army” as a primary subject since 2014. In this vein, Pines takes human nature to be a "second pillar" of fa political philosophy, as eschewing its discussion. The "overwhelming majority of humans are selfish and covetous", which is not taken to be alterable, but rather "can become an asset to the ruler rather than a threat." In this regard, Han Fei is an addendum to Gongsun Yang, with Shen Dao contributing.

Kenneth Winston emphasizes the welfare espoused by Han Fei, but while Han Fei espoused that his model state would increase the quality of life, Schneider (2018) reviews this as not being considered this a legitimizing factor, but rather, a side-effect of good order. Han Fei focused on the functioning of the state, the ruler's role as guarantor within it, and aimed in particular at making the state strong and the ruler the strongest person within it.

Adventures in Chinese Realism (2022)[58]

References

- 1 2 Garfield, Jay L.; Edelglass, William (9 June 2011). The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. OUP USA. ISBN 9780195328998 – via Google Books.

- ↑

- Tao Jiang 2021. p238. Origins of Moral-Political Philosophy in Early China

- Pines, Yuri (2023), "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Goldin, Paul R. (March 2011). "Persistent misconceptions about Chinese 'Legalism'". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 38 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.2010.01629.x.

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner.1970,1982. p93,119-120. What Is Taoism?

- Donald H Bishop 1995. p81-82. Chinese Thought

- Michael Loewe 1978/1986. p526. Cambridge History of China Volume I

- Waley, Arthur (1939). p194. Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China.

- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011. p59 Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- Hansen, Chad. Philosophy East & West. Jul94, Vol. 44 Issue 3, p435. 54p. Fa (standards: laws) and meaning changes in Chinese philosophy

- ↑

- A.C. Graham 1989. p269 https://books.google.com/books?id=QBzyCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA269

- Tao Jiang 2021. p238. https://books.google.com/books?id=qXo_EAAAQBAJ&pg=PA238

- While the idea of them as simply Machiavellians would be criticized by Benjamin Schwarz and Graham, as dating back to Creel, the idea of Shen Buhai and Han Fei as model builders is criticized modernly by Goldin's 2011 Persistent Misconceptions, but recalled by Pines Stanford. Winston 2005, Peng He 2014, and Tao Jiang (2021) criticize the idea of them as simply amoral realists; Pines starts with amorality, but qualifies it. Hence, in the interest of scientific spirit, they are comparisons rather than simply analogies.

- ↑ Feng Youlan 1948. p.37. A short history of Chinese philosophy

- Chen, Jianfu (1999). Chinese Law: Towards an Understanding of Chinese Law, Its Nature and Development. The Hague: Kluwer Law International. p. 12. ISBN 9041111867.

- ↑ Jacques Gernet 1982. p. 90. A History of Chinese Civilization. https://books.google.com/books?id=jqb7L-pKCV8C&pg=PA90

- ↑ Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, p. 60 The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy https://books.google.com/books?id=I0iMBtaSlHYC&pg=PA60

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner (15 September 1982). p103. What Is Taoism?: And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226120478 – via Google Books

- Hengy Chye Kiang 1999. p. 44. Cities of Aristocrats and Bureaucrats. https://books.google.com/books?id=BIgS4p8NykYC&pg=PA44

- Rubin, Vitaliĭ, 1976. p55. Individual and state in ancient China : essays on four Chinese philosophers

- ↑ Yu-lan Fung 1948. p. 157. A Short History of Chinese Philosophy. https://books.google.com/books?id=HZU0YKnpTH0C&pg=PA157

- Eno, Robert (2010), Legalism and Huang-Lao Thought (PDF), Indiana University, Early Chinese Thought Course Readings

- Hu Shi 1930: 480–48, also quoted Yuri Pines 2013. Birth of an Empire

- Graham 1989. 268

- Paul R. Goldin 2011. Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism. https://www.academia.edu/24999390/Persistent_Misconceptions_about_Chinese_Legalism_

- ↑ Chen, Chao Chuan and Yueh-Ting Lee 2008 p. 12. Leadership and Management in China

- 1 2 3 Bishop, Donald H. (27 September 1995). Chinese Thought: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120811393.

- ↑ Kenneth Winston p. 315. Singapore Journal of Legal Studies [2005] 313–347. The Internal Morality of Chinese Legalism. http://law.nus.edu.sg/sjls/articles/SJLS-2005-313.pdf

- ↑ Graham, A. C. 1989/2015. p283. Disputers of the Tao.

- Creel, 1974. p4–5. Shen Pu-hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B.C.

- 1 2 Creel, Herrlee Glessner (15 September 1982). What Is Taoism?: And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226120478 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), 1.2 Historical Context. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/chinese-legalism/

- ↑ Eno (2010), p. 1.

- ↑ Chad Hansen, University of Hong Kong. Lord Shang. http://www.philosophy.hku.hk/ch/Lord%20Shang.htm

- ↑ Charles Holcombe 2011 p. 42. A History of East Asia. https://books.google.com/books?id=rHeb7wQu0xIC&pg=PA42

- ↑ K. K. Lee, 1975 p. 24. Legalist School and Legal Positivism, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 2.

- ↑ Yu-lan Fung 1948. p. 155. A Short History of Chinese Philosophy. https://books.google.com/books?id=HZU0YKnpTH0C&pg=PA155

- ↑ Herrlee G. Creel, 1974 p. 124. Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1

firm hand, devolution, aristocratic lineages:- Edward L. Shaughnessy. China Empire and Civilization p26

- Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", 1.2 Historical Context.

- ↑ David K Schneider May/June 2016 p. 20. China's New Legalism

- ↑ Knoblox Xunzi 148

- ↑ Hansen, Chad (17 August 2000). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195350760 – via Google Books.

- ↑ K. K. Lee, 1975 p. 26. Legalist School and Legal Positivism, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 2.

- ↑ Waley, Arthur (1939). Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. p. 194.

- ↑ Huang, Ray, China A Macro History. p.20.

Daoists little respect for mundane authority.- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, p. 65 The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- ↑

- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011. p59. Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- Fraser, Chris, "Mohism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/mohism/

- Creel 1974 p148. Shen Pu-hai

- Graham 1989. p273-275,283,284 Disputers of the Tao. https://books.google.com/books?id=QBzyCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA273

- Donald H Bishop 1995. p81. Chinese Thought

- Benjamin Schwarz. p.322. The World of Thought in Ancient China

- Zhenbin Sun 2015. p. 18. Language, Discourse, and Praxis in Ancient China.

- Zhongying Cheng 1991 p.315. New Dimensions of Confucian and Neo-Confucian Philosophy. https://books.google.com/books?id=zIFXyPMI51AC&pg=PA315

- Xing Lu 1998. p262. Rhetoric in Ancient China, Fifth to Third Century, B.C.E.

- Benjamin Elman, Martin Kern 2010 p.17,41,137 Statecraft and Classical Learning: The Rituals of Zhou in East Asian History https://books.google.com/books?id=SjSwCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA41

- Dingxin Zhao 2015 p.72. The Confucian-Legalist State. https://books.google.com/books?id=wPmJCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA72

- ↑

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-legalism/

- Section split, sources in "Characterization" section, will sort out

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy. p492 https://books.google.com/books?id=yTv_AQAAQBAJ&pg=PA492

- ↑

- Makeham 1994 p81. https://books.google.com/books?id=GId_ASbEI2YC&pg=PA81

- Peng He. p83-85 Chinese Lawmaking. https://books.google.com/books?id=MXDABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA83

- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, p.59 The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- Creel 1970. p112. What is Taoism. https://archive.org/details/whatistaoismothe0000cree/page/112/mode/2up

- Kidder Smith. p141-144. Sima Tan and the Invention of Daoism

- ↑

- Fraser, Chris, "School of Names", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Kenneth Winston 2005. Internal Morality of Chinese Legalism

- Kidder Smith. p141-144. Sima Tan and the Invention of Daoism

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner.1970. p119-120. Will require a review

- Creel 1970, p90-91,100-101,106-107,113, What Is Taoism?

- ↑

- Makeham 1994. p67,70. Name and Actuality

- Hansen 1992. p359,368,375. daoist theory

- Joseph Needham 1956.206. Science and Civilization in China Volume 2

- Goldin 2011. p10. persistent misconceptions.

- Lü Peng 2023. p44. A History of China in the 20th Century

- Tao Jiang 2021 p237-239

- Pines 2013. p77. Submerged by Absolute Power

- Creel 1974 p4,44,55

- Winston 2005 p331

- Harris 2016, 24

- Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2023/entries/chinese-legalism/>

- ↑ Tao Jiang 2021. p235.

- Creel 1974, 159

- Kidder Smith. p141-144. Sima Tan and the Invention of Daoism

- ↑

- Creel, 1974. p32,147-148. Shen Pu-hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B.C.

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner.1970. What Is Taoism?: And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History

- Yuri Pines. 2019. p689. Worth Vs. Power: Han Fei’s “Objection to Positional Power” Revisited

- ✓ Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011. p59,63. Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- Graham, A. C. 1989/2015.268

- Yuri Pines. 2019. p689. Worth Vs. Power: Han Fei’s “Objection to Positional Power” Revisited

- Goldin 2011. 8-10

- ↑ Creel's Branches Shendao ref

- Benjamin I. Schwarz 1985. p. 247. The World of Thought in Ancient China. https://books.google.com/books?id=kA0c1hl3CXUC&pg=PA247

- Bishop, Donald H. (September 27, 1995). P,81,93 Chinese Thought: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120811393.'

- Vitali Rubin, "Shen Tao and Fa-chia" Journal of the American Oriental Society, 94.3 1974,pp. 337-46

- ↑ Creel 1974: 380

- ↑ Shang Yang (encyclopedic)

- Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", 2014

- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy; p66 measures and weights.

- Stephen Angle 2003/2013 p.537, Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy

- ↑ Shang Yang

- Bodde, Derk (1986). "The State and Empire of Ch'in". In Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China Volume I: Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. -- A.D. 220. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243278.

- Chad Hansen, 1992. 359. A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation.

- Paul R. Goldin, "Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism". pp. 16–17

- Erica Brindley. p.6,8. The Polarization of the Concepts Si (Private Interest) and Gong (Public Interest) in Early Chinese Thought.

- K. K. Lee, 1975 pp. 27–30, 40–41. Legalist School and Legal Positivism, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 2.

- ↑ Eirik Lang Harris 2013 pp. 1,5 Constraining the Ruler

- ↑ Chen, Chao Chuan and Yueh-Ting Lee 2008 p. 115. Leadership and Management in China

- ↑ Yuri Pines 2003 pp. 78,81. Submerged by Absolute Power

- ↑ Chen Qiyou 2000: 18.48.1049; 20.54.1176; 2.6.111; 17.45.998

- 1 2 Graham, A. C. (15 December 2015). Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. Open Court. ISBN 9780812699425 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Enlightened Absolutism

- Tao Jiang 242

- Creel 1974. 6

- Xuezhi Guo p. 141 The Ideal Chinese Political Leader. https://books.google.com/books?id=6vG-MROnr7IC&pg=PA141

- Benjanmin I. Schwartz p. 345, The World of Thought in Ancient China

- Graham 1989: 291

- Xing Lu 1998. Rhetoric in Ancient China, Fifth to Third Century, B.C.E.. p. 264. https://books.google.com/books?id=72QURrAppzkC&pg=PA258

- Yuri Pines 2003 p. 81. Submerged by Absolute Power

- ↑

- ↑ Hansen 1992. p359

- Tao Jiang 2021. 420

- 2023. Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", Stanford Encyclopedia . <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2023/entries/chinese-legalism/>

- ↑ Jingyuan Ma, Mel Marquis 2022. p.295Confucian Culture and Competition Law in East Asia

- ↑ Sima Tan's Fajia

- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011, p.59,65-67 The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- Kidder Smith. p141-144. Sima Tan and the Invention of Daoism

- Creel 1970.p92-93 https://archive.org/details/whatistaoismothe0000cree/page/112/mode/2up

- Graham 1989. p268 https://books.google.com/books?id=QBzyCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA268

- Hansen 1992. p359 https://books.google.com/books?id=nzHmobC0ThsC&pg=PA359

- Feng Youlan 1948. p157.

- Joseph Needham 1956.206. Science and Civilization in China Volume 2

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-legalism/#RewaRankMeri

- Michael Loewe 1978/1986. p526,534-345. The Cambridge History of China Volume I: Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. -- A.D. 220.

- Derk Bodde 1981. p16,175. Essays on Chinese Civilization

- Bo Mou 2009. p208. Routledge History of Chinese Philosophy.

- (R. Eno), 2010 pp. 1–4. Legalism and Huang-Lao Thought. Indiana University, Early Chinese Thought [B/E/P374].

- ↑ Coining of the Fajia

- Makeham, John (1990). "THE LEGALIST CONCEPT OF HSING-MING: An Example of the Contribution of Archaeological Evidence to the Re-Interpretation of Transmitted Texts". Monumenta Serica. 39: 92. doi:10.1080/02549948.1990.11731214. JSTOR 40726902.

- Kidder Smith. p141-144. Sima Tan and the Invention of Daoism

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner.1970. p119-120. Will require a review

- Creel 1970, p90-91,100-101,106-107,113, What Is Taoism?

- Makeham 1990. THE LEGALIST CONCEPT OF HSING-MING

- Makeham 1994 70. Name and Actuality in Early Chinese Thought

- Creel, 1974. p122,159. Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-legalism/#RewaRankMeri

- Michael Loewe 1978/1986. p74-75,526,534. The Cambridge History of China Volume I: Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. -- A.D. 220.

- Derk Bodde 1981. p16,175. Essays on Chinese Civilization

- Michael Loewe 1978/1986. The Cambridge History of China Volume I: Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. -- A.D. 220.

- Feng Youlan 1948. p.30-34,157. A short history of Chinese philosophy

- ↑ Huang-Lao Daojia

- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011. p47. Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- Graham, A. C. 1989/2015. Disputers of the Tao.

- Hansen, Chad 1992/2000. p345,350,401. A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation

- ✓ Paul R. Goldin 2011. p2. Persistent Misconceptions about Chinese Legalism.

- Waley, Arthur (1939). p153-154. Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China.

- Herrlee G. Creel, 1974. p123-124. Shen Pu-Hai: A Secular Philosopher of Administration, Journal of Chinese Philosophy Volume 1.

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner 1970. What Is Taoism?

- Thomas Michael, Religions 2022, The Original Text of the Daodejing. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/13/4/325

- ↑ Daojia and Daoist references

- Cao, F. (2017). Introduction: On the Huang-Lao Tradition of Daoist Thought. In: Daoism in Early China. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-55094-1_1

- ✓ Benjamin Schwarz. The World of Thought in Ancient China p.237.

- Daniel Coyle 1999. Guiguzi: On the Cosmological Axes of Chinese Persuasion. p.114.

- Allyn Ricket. 2001. p19. Guanzi Volume 1 p19. Shendao

- Hansen, Chad, "Daoism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/daoism/

- ↑ Arguments for Daoist influence

Earlier based in Kayrn Lai (2008), Pines still does not regard Daoism as evidential outside a few chapters.

- Yuri Pines (2022) Han Feizi and the Earliest Exegesis of Zuozhuan, Monumenta Serica, 70:2, 341-365, DOI: 10.1080/02549948.2022.2131797

Moody represents a disciplined comparison without assumption of Daoist influence. Referencing moody, Mingjun argues for natural-law Daoism in the Han Feizi that would typically be associated with the Han dynasty Huainanzi.- Peter R. Moody 2011. Han Fei in his Context: Legalism on the Eve of the Qin conquest. John Wiley and Sons; Wiley (Blackwell Publishing); Blackwell Publishing Inc.; Wiley; Brill (ISSN 0301-8121), Journal of Chinese Philosophy, #1, 38, pages 14-30, 2011 feb 24

- Mingjun Lu 2016. p.344. "Implications of Han Fei’s Philosophy". Journal of Chinese Political Science.

a disciplinary rejection of assumed daoist influence does not appear to necessarily be shared by the Chinese, or otherwise at any rate by persons prior the Oxford. Prior represented in Creel, its discipline is rooted in Graham 1989/Hansen 1992 as represented in the Oxford 2011.

Professor Xing-Lu (1998), based in the west although prior the Oxford, references their work, but either doesn't agree with their conclusions or ignores them in terms of Daoism and Fa as requiring no connection to punishment. Peng He, located in Beijing, simply references Sima Qian out of hand for theory of Daoist origin, despite otherwise quality content.

- Xing Lu 1998. p264. Rhetoric in Ancient China, Fifth to Third Century, B.C.E.

- Peng He 2014. p. 69. Chinese Lawmaking: From Non-communicative to Communicative.

- Kejian, Huang 2016. p180. From Destiny to Dao: A Survey of Pre-Qin Philosophy in China.

- ↑

- Waley, Arthur (1939). Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. p. 194.

- Jay L. Garfield, William Edelglass 2011. p59 Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy

- Graham, A. C. 1989/2015. p269. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. Open Court. ISBN 9780812699425 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Goldin, Paul R. (March 2011). "Persistent misconceptions about Chinese 'Legalism'". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 38 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.2010.01629.x.

- 1 2 Pines, Yuri (2023), "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", in Zalta, Edward N.; Nodelman, Uri (eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2023 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 23 August 2023

- ↑

- Graham, A. C. 1989/2015. p268-269. Disputers of the Tao.

- Eirik Lang Harris 2016 p24. The Shenzi Fragments

- Tao Jiang 2021. p235-236,267

- ↑ Tao Jiang 2021. p36-37,238,244. Origins of Moral-Political Philosophy in Early China

- ↑ Creel 1970. p51. What is Taoism.

- ↑ Various modern scholarship. 10/20/23

- Hansen 1992. p362. Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought

- Ross Terril 2003 pp. 68–69. The New Chinese Empire https://books.google.com/books?id=TKowRrrz5BIC&pg=PA68

- Chen, Chao Chuan and Yueh-Ting Lee 2008 p111. Leadership and Management in China.

- Han Fei, De, Welfare. Schneider, Henrique. Asian Philosophy. Aug2013, Vol. 23 Issue 3, p260-274. 15p. DOI: 10.1080/09552367.2013.807584., Database: Academic Search Elite

- "Pines, Yuri, "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", 1. 2. Philosophical Foundations. rich state and powerful army, 5.1 The Ruler’s Superiority

Sources and further reading

- Pines, Yuri (2023), "Legalism in Chinese Philosophy", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 28 January 2022

- Lai, Karyn L. (2008), An Introduction to Chinese Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-47171-8.

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner. What Is Taoism?: And Other Studies in Chinese Cultural History (1982)

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner. Shen Pu-hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B.C. (1974)

- Goldin, Paul R. (March 2011). "Persistent misconceptions about Chinese 'Legalism'". Journal of Chinese Philosophy. 38 (1): 88–104. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.2010.01629.x. See also

- Goldin, Paul R. (2011), "Response to editor", Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 38 (2): 328–329, doi:10.1111/j.1540-6253.2011.01654.x.