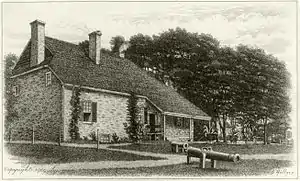

Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site | |

West (front) elevation, 2006 | |

| |

Interactive map showing Washington’s Headquarters | |

| Location | Newburgh, New York |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°29′52″N 74°00′36″W / 41.49778°N 74.01000°W |

| Area | 7 acres (2.8 ha) |

| Built | 1750 |

| Architectural style | Dutch Colonial, Federal Revival |

| Website | https://parks.ny.gov/historic-sites/17/details.aspx |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000887 |

| NYSRHP No. | 07140.000021 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | January 20, 1961[2] |

| Designated NYSRHP | June 23, 1980 |

Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site, also called Hasbrouck House, is located in Newburgh, New York, United States, overlooking the Hudson River. George Washington lived there while he was in command of the Continental Army during the final year of the American Revolutionary War; it had the longest tenure as his headquarters of any place he had used.[3]

In 1961 the house was designated a state historic site. It is also the oldest house in the city of Newburgh, and the first property acquired and preserved by any U.S. state for historic reasons.[4]

History

The first fieldstone farmhouse on the site may have been built in 1725 by Burger Mynderse. The property was sold to Elsie Hasbrouck, and she in turn gave it to her son, Jonathan, who married Catherine (Tryntje) Dubois and they built the existing structure on the original foundation, if any, in 1750. The house was surrounded by a large stock farm. The home underwent two significant enlargements before it was completed in 1770. The home has an original "Dutch Jambless" fireplace. A temporary kitchen was built by the Continental Army upon their arrival in 1782. Other changes were made inside the house including the addition of an "English" style fireplace in General Washington's bedroom. Existing buildings such as stables and barns were also enlarged and improved on the site. Most Army buildings were removed by the Quartermaster-General's Office at the end of the war, with the exception of a "House in the garden", which was given to Mrs. Hasbrouck. It no longer exists.

In 1850, it was acquired by the State of New York and became the first publicly operated historic site in the country.[3] Today, it is a museum furnished to recreate its condition during the Revolutionary War. It covers an area of about seven acres (2.8 ha), with three buildings: Hasbrouck House, a museum (built in 1910), a monument named the "Tower of Victory", which was completed in 1887 in commemoration of the centennial of successful disbandment of the Continental Army, and a maintenance shed/garage built in the Colonial Revival style in 1942.[3]

Also on the property is the grave of Uzal Knapp, one of the longest-lived veterans of the Continental Army. For many years it was believed that he had served as one of Washington's personal guards, but more recently historians have come to doubt this.[5]

There is a statue entitled The Minuteman, by Henry Hudson Kitson, that was erected on the grounds on November 11, 1924.[6]

The site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961.[2]

Washington's Headquarters

In April 1782, General George Washington made his headquarters at the farmhouse of the Hasbrouck family, making Newburgh the Continental Army's headquarters; he remained there until August 1783. This was Washington's longest stay at any of his over 160 headquarters.[7]

In March 1782, Washington received the famous Newburgh letter from Lewis Nicola, suggesting that he declare himself king of the United States, a suggestion he strongly rejected. In honor of that rejection, Kings Highway, the north–south street on which the Newburgh headquarters is located, was renamed Liberty Street.[8]

On August 7, 1782, while the Continental troops were encamped around the vicinity of the House, Washington issued a general order which established the Badge of Military Merit, to enlisted men and non-commissioned officers for long and faithful service and for acts of heroism. 150 years later, in 1932, the Badge would be revived and renamed as the famous Purple Heart. Headquarters Newburgh was the first place the badge of merit was awarded to American troops.[9]

On August 31, Washington departed Newburgh Headquarters and marched the army southward to Verplanck's Point.[10] There, Washington staged a review of the Continental Army as an honor for the departing French Commander-in-Chief Comte de Rochambeau and his army, who had arrived there a few days prior. Washington wrote of the display:

"As the intention of drawing out the troops tomorrow is to compliment his Excellency the Count de Rochambeau; The troops as he passes them shall pay him the honors due the commander in chief... On this occasion the tallest men are to be in the front rank."[11]

A few days later, the French and American armies departed, and Washington resumed his residence at the Hasbrouck House.

In March 1783, feeling embittered over their lack of payment from Congress and secretly manipulated by a faction of nationalist politicians in Philadelphia (usually given as Robert Morris, Gouverneur Morris, and Alexander Hamilton), senior officers of the army encamped at the nearby New Windsor Cantonment began circulating an anonymously authored letter; it called for a meeting of all field officers and company representatives to decide what course of action the army should take against Congress. The letter's author advocated for an ultimatum stating that if peace was declared and the officers were still unpaid, they would refuse to disband the army and possibly march against Congress. This would effectively be a military mutiny against the civilian government, that could rapidly devolve into a military coup d'etat. Now known to be the work of Major John Armstrong, Jr., an aide-de-camp of General Horatio Gates, this letter inflamed tensions amongst the officers to dangerous new levels and began what is now known as the Newburgh Conspiracy. Washington, fearing an armed confrontation would be too grave a threat to democracy, confronted the threat head on. After delivering the Newburgh Address and reading aloud a letter from Congressman Joseph Jones of Virginia, he was able to persuade his officers abandon the conspiracy and to instead remain loyal to Congress, to him, and to their republican principles.[12]

A month later, Washington delivered the Proclamation of the Cessation of Hostilities that announced the preliminary peace treaty with the United Kingdom, and ordering the army to officially stand down. This marked the effective end of the fighting of the American Revolution, exactly 8 years later to the day since the fighting began at the Battles of Lexington and Concord.[13][14]

While Washington was headquartered in Newburgh, the main bulk of the Continental Army was encamped nearby at the New Windsor Cantonment near what is today known as Vails Gate, a few miles to the southwest. There were roughly 7,500 troops of the Army as well as 500 women and children as camp followers.

Tower of Victory

On the northeast corner of the site grounds is a large stone monument called the Tower of Victory. Opened to the public in 1887, it commemorates the centennial of the successful disbandment of the Continental Army. The date of the Army's disbandment is given on the commemoration plaque of the Tower as October 13, 1783; construction on the Tower was delayed, so it did in fact miss its own centennial.

The Tower was a joint Federal and State project; the commission that oversaw the planning, design and construction of the Tower was headed up by then-Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln's son. The commission selected architect John H. Duncan to design the monument, who would later design Grant's Tomb; he briefly considered an obelisk, but as the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C. was languishing in construction limbo for over 30 years, he instead settled on the current design. It is meant to be a crude but imposing structure, reminiscent of the revolutionary times; it is surmounted by an accessible outlook, which is open to the public through guided tours.

There are four bronze statues on the exterior of the Tower, two facing the West and two facing the East. Sculpted by William Rudolf O'Donovan in 1888, the statues depict a Rifleman (Northeast corner), a Light Dragoon (Southeast corner), an Artilleryman (Northwest corner), and Infantry Line Officer (Southwest corner). Inside the atrium of the Tower was a life-sized statue of George Washington, also sculpted by O'Donovan; small cracks were discovered during maintenance of the statue in 2020, so it is now off-site undergoing repairs.

In 1950, hurricane-force winds blew up the Hudson River and tore the original roof off of the Tower. The monument closed, pending repairs; sufficient funds were not raised until 2019, and finally a new roof was installed.

Honors and commemoration

On July 4, 1850 Major General Winfield Scott raised a flag at the opening ceremony and dedication for Washington's headquarters.[15] The U.S. Post Office issued a commemorative stamp featuring an accurate depiction of Washington's Headquarters at Hasbrouck House, overlooking the Hudson River, at Newburgh, New York, on April 19, 1933, the 150th anniversary of the Proclamation of Peace.[14]

See also

- List of Washington's Headquarters during the Revolutionary War

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Orange County, New York

- Knox's Headquarters State Historic Site, headquarters of General Henry Knox, also a National Historic Landmark in New Windsor

- New Windsor Cantonment State Historic Site, final encampment of Continental Army in nearby New Windsor

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- 1 2 "Washington's Headquarters". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 18, 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site". parks.ny.gov. New York State. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ↑ "City Parks". City of Newburgh. October 27, 2023. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ↑ Godfrey, p. 15

- ↑ "The Minuteman". hmdb.org. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ↑ "'You Are Needed at Headquarters' at New Windsor Cantonment". newyorkalmanack.com. August 19, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ↑ "Newburgh History". March 31, 2015. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ↑ Godfrey, 1904, p. 81

- ↑ Godfrey, 1904, p. 82

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, p. 157

- ↑ Kohn, "Inside History", pp 188–220

- ↑ Grizzard, pp. 236-37

- 1 2 "Peace of 1783 Issue". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- ↑ Schenkman, p. 74

Bibliography

- Baldwin, John. History and guide to Newburgh and Washington's headquarters, and a catalogue of manuscripts and relics in Washington's headquarters. New York: N. Tibballs & sons., E-book

- Fitzpatrick, John (1931). The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Fleming, Thomas (2007). The Perils of Peace: America's Struggle for Survival After Yorktown. New York: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 9780061139109.

- Godfrey, Carlos Emmor (1904). The Commander-in-chief's Guard, Revolutionary War. Stevenson-Smith Company., E'book

- Grizzard, Frank E. (2002). George Washington: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO., Book

- Head, David (2019). A Crisis of Peace: George Washington, the Newburgh Conspiracy, and the Fate of the American Revolution. New York: Pegasus Books. ISBN 1643130811.

- Kohn, Richard H (1970). "The Inside History of the Newburgh Conspiracy: America and the Coup d'Etat". The William and Mary Quarterly. 27 (Third Series, Volume 27, No. 2): 188–220. doi:10.2307/1918650. JSTOR 1918650.

- McGurty, Michael S. (2023). George Washington Versus the Continental Army: Showdown at the New Windsor Cantonment, 1782-1783. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 1476692378.

- Rappleye, Charles (2010). Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781416570912.

- Schenkman, A. J. (2008). Washington's Headquarters in Newburgh. Arcadia Publishing., Book

External links

- Official site: Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site, at New York State

- Site Report by Save America's Treasures

- Story on Washington in Newburgh

- Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area

- 26 photos of Hasbrouck House / Washington's Headquarters (click icon at top left), at Historic American Buildings Survey

- Renovation of the George Washington Headquarters