Slavery in South Carolina was widespread and systemic even when compared to other slave states. Although African slavery was not mentioned in the “Declarations and Proposals to all that will Plant in Carolina” (1663), which distributed land using the headright system, the Lords Proprietors revised their stance to accommodate the wishes of the Barbadian settlers[1]; these settlers, whom the Lords Proprietors sought to attract to the colony, expressed a desire to bring their enslaved African laborers with them.[1]

South Carolina's first governor, William Sayle, set a precedent by bringing three Black people "in the founding fleet in 1670 and another a few months later." Similar to Virginia, numerous enslaved people in South Carolina were imported from the West Indies,[1] with the majority from the British colony of Barbados;[2] they were considered to have a certain level of immunity to diseases like malaria and yellow fever that were common in the region, and they were proficient in making use of native plants for medicine in order to could cope with the semitropical environment.[1] During the early settlement in South Carolina, enslaved Africans imported from the West Indies could more easily live off the land because had some advantages over their European enslavers, such as their knowledge of tropical herbs, their superior fishing skills, and their ability to canoe or pirogue along inland waterways.[1]

South Carolina was the only English colony in North America that favored African labor over White indentured servitude and Indigenous labor. South Carolina had the highest ratio of Black slaves to White colonists in English North America,[3] with the Black population reaching sixty percent of the total population by 1715.[1] The region had a Black majority throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries until the mid-twentieth century.[2][4][5] Slave labor allowed South Carolina to become the wealthiest colony in the Americas by the mid-1760s.[2] On the verge of the American Civil War, "45.8 percent of White families in the state owned slaves."[4] Under South Carolina law, enslaved people were "deemed, sold, taken, reputed and adjudged in law, to be chattels, personal in the hands of their owners and possessors, and their executors, administrators, and assigns, TO ALL INTENTS, CONSTRUCTIONS AND PURPOSES WHATSOEVER...A slave is not generally regarded as legally capable of being within the peace of the State. He is not a citizen, and is not in that character entitled to her protection."[6]

Enslaved African people's relationship with Indigenous people

Africans and Native Americans had basket-weaving traditions and were skilled in the use of small watercraft on inland rivers.[1] Since both peoples shared similar outlooks on land, nature, and materialism, they were in close contact.[1] Enslaved Africans were one of the first peoples to appropriate native languages and local skills, so they were commonly used as translators and mediators of knowledge between Europeans and Native Americans.[1]

Rice and indigo plantations

During the 1700s, French and British settlers built rice and indigo plantations that enslaved people worked on.[2] During the start of the eighteenth century, rice became a South Carolinian staple, and by 1740, indigo became a profitable staple crop while remaining less popular than rice.[1] Many African enslaved people were knowledgeable about the cultivation of rice since many of them came from rice-growing regions in Africa.[1] English rice plantation owners reaped the benefits of their enslaved people's rice-related agricultural knowledge, so they preferred to import enslaved people from the rice-producing Senegambia region.[1] Originally, rice was grown on dry upland soils, then it changed to inland swamps; at the end of the eighteenth century, rice cultivation was adapted to tide flow, and the rice fields were built near rivers in low-lying regions.[1] Even though this new system did not require as much weeding, enslaved people's workloads increased as these fields required the building of levees, large dikes, and canals by hand, working in the mud with alligators, snakes and other vermin, and they had to be maintained.[1]

Cotton plantation and production

Originally, cotton was cultivated mainly for domestic use, primarily for Black enslaved people.[1] Plantations were usually run entirely by enslaved people, and the plantation owners were accepting of this arrangement as it encouraged enslaved people to remain loyal, thereby preventing fleeing.[1] During the American Revolutionary Period, crops took priority on plantations while cotton cultivation and production were predominately for the use of local textile manufacturers.[1]

Transatlantic Slave Trade

Charleston was a major hub of both the transatlantic and interstate slave trades. The South Carolina General Assembly reopened the port of Charleston to the transatlantic slave trade between 1803 and 1807, during which time some 50,000 enslaved Africans were imported to the state; this trade was finally cut off by the 1808 federal law Prohibiting Importation of Slaves.[7] Historian Frederic Bancroft found that there were no fewer than 50 slave traders, called "brokers" in Charlestonian parlance, working in the city in 1859–60.[8]

Gallery

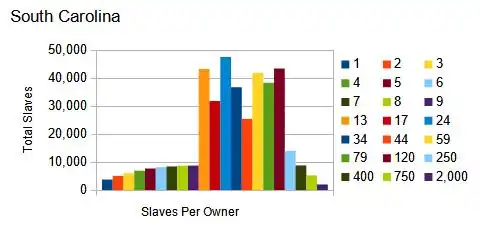

1860 US census, South Carolina, number of slaves per owner

1860 US census, South Carolina, number of slaves per owner_(14780245224).jpg.webp) Illustration from Frederick Law Olmstead's A journey in the seaboard slave states - with remarks on their economy (1856)

Illustration from Frederick Law Olmstead's A journey in the seaboard slave states - with remarks on their economy (1856) African Americans outside a building preparing cotton for the cotton gin, possibly at Smith's plantation, Port Royal

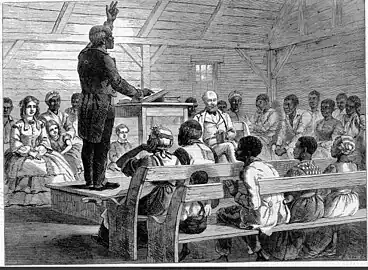

African Americans outside a building preparing cotton for the cotton gin, possibly at Smith's plantation, Port Royal Plantation slave chapel worship, South Carolina, 1863

Plantation slave chapel worship, South Carolina, 1863

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Littlefield, Daniel C. "Slavery". South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 History.com Editors. "South Carolina". HISTORY. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

{{cite web}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ↑ Grant, Daragh (July 2015). ""Civilizing" the Colonial Subject: The Co-Evolution of State and Slavery in South Carolina, 1670-1739". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 57 (3): 607 – via ProQuest.

- 1 2 "Slavery". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-08-07.

- ↑ "African Passages, Lowcountry Adaptations". Lowcountry Digital Library at the College of Charleston. 2013. Retrieved 2023-08-08.

- ↑ Stowe, Harriet Beecher (1853). A key to Uncle Tom's cabin: presenting the original facts and documents upon which the story is founded. Boston: J. P. Jewett & Co. pp. 164, 284. LCCN 02004230. OCLC 317690900. OL 21879838M.

- ↑ "Reconfiguring the Old South: Solving the Problem of Slavery, 1787–1838 by Lacy Ford (Teaching the Journal of American History)". archive.oah.org. Retrieved 2023-09-02.

- ↑ Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931, 1996]. "Chapter VIII: The Height of the Slave Trade in Charleston". Slave Trading in the Old South (Original publisher: J. H. Fürst Co., Baltimore). Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

Further reading

- Ashton, Susanna, ed. (2012). I Belong to South Carolina: South Carolina Slave Narratives. University of South Carolina Press.

- Hill Edwards, Justene (2021). Unfree Markets: The Slaves' Economy and the Rise of Capitalism in South Carolina. Columbia studies in the history of U.S. capitalism. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54926-4. LCCN 2020038705.

- Hudson, Larry E. (2010). To Have and to Hold: Slave Work and Family Life in Antebellum South Carolina. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press.

- Sinha, Manisha (2003). The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina. University of North Carolina Press.

- Wood, Peter (2012). Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion. Knopf Doubleday.

- Pearson, Edward (2023). The Enslaved and Their Enslavers: Power, Resistance, and Culture in South Carolina, 1670–1825. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-1-5128-2439-1.