The history of Nigeria can be traced to the earliest inhabitants whose remains date from at least 13,000 BC through early civilizations such as the Nok culture which began around 1500 BC. Numerous ancient African civilizations settled in the region that is known today as Nigeria, such as the Kingdom of Nri,[1] the Benin Empire,[2] and the Oyo Empire.[3] Islam reached Nigeria through the Bornu Empire between (1068 AD) and Hausa Kingdom during the 11th century,[4][5][6][7] while Christianity came to Nigeria in the 15th century through Augustinian and Capuchin monks from Portugal to the Kingdom of Warri.[8] The Songhai Empire also occupied part of the region.[9] From the 15th century, European slave traders arrived in the region to purchase enslaved Africans as part of the Atlantic slave trade, which started in the region of modern-day Nigeria; the first Nigerian port used by European slave traders was Badagry, a coastal harbour.[10][11] Local merchants provided them with slaves, escalating conflicts among the ethnic groups in the region and disrupting older trade patterns through the Trans-Saharan route.[12]

Lagos was occupied by British forces in 1851 and formally annexed by Britain in the year 1865.[13] Nigeria became a British protectorate in 1901. The period of British rule lasted until 1960 when an independence movement led to the country being granted independence.[14] Nigeria first became a republic in 1963, but succumbed to military rule after a bloody coup d'état in 1966. A separatist movement later formed the Republic of Biafra in 1967, leading to the three-year Nigerian Civil War.[15] Nigeria became a republic again after a new constitution was written in 1979. However, the republic was short-lived, as the military seized power again in 1983 and later ruled for ten years. A new republic was planned to be established in 1993 but was aborted by General Sani Abacha. Abacha died in 1998 and a fourth republic was later established the following year, 1999, which ended three decades of intermittent military rule.

Prehistory

Acheulean tool-using archaic humans may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP (Middle Pleistocene).[16]

By at least 61,000 BP, Middle Stone Age West Africans may have begun to migrate south of the West Sudanian savanna, and, by at least 25,000 BP, may have begun to dwell near the coast of West Africa.[17]

An excessively dry Ogolian period occurred, spanning from 20,000 BP to 12,000 BP.[18] By 15,000 BP, the number of settlements made by Middle Stone Age West Africans decreased as there was an increase in humid conditions, expansion of the West African forest, and increase in the number of settlements made by Late Stone Age West African hunter-gatherers.[19] Iwo Eleru people persisted at Iwo Eleru, in Nigeria, as late as 13,000 BP.[20]

Macrolith-using late Middle Stone Age peoples, who dwelled in Central Africa, to western Central Africa, to West Africa, were displaced by microlith-using Late Stone Age Africans as they migrated from Central Africa into West Africa.[21] After having persisted as late as 1000 BP,[22] or some period of time after 1500 CE,[23] remaining West African hunter-gatherers were ultimately acculturated and admixed into the larger groups of West African agriculturalists.[22]

The Dufuna canoe, a dugout canoe found in northern Nigeria has been dated to around 6300 BCE,[24] making it the oldest known boat in Africa, and the second oldest worldwide.[24][25]

Iron Age

Archaeological sites containing iron smelting furnaces and slag have been excavated at sites in the Nsukka region of southeast Nigeria in what is now Igboland: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[26][27] and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).[27][28] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BCE and 550 BCE.[29][30] More recently, Bandama and Babalola (2023) have indicated that iron metallurgical development occurred 2631 BCE – 2458 BCE at Lejja, in Nigeria.[31]

Nok culture

Nok culture may have emerged in 1500 BCE and continued to persist until 1 BCE.[32] Nok people developed terracotta sculptures through large-scale economic production,[33] as part of a complex funerary culture[34]. The earliest Nok terracotta sculptures may have developed in 900 BCE.[32] Some Nok terracotta sculptures portray figures wielding slingshots, as well as bows and arrows, which may be indicative of Nok people engaging in the hunting, or trapping, of undomesticated animals.[35] A Nok sculpture portrays two individuals, along with their goods, in a dugout canoe.[35] This indicates that Nok people used dugout canoes to transport cargo, and tributaries.[36] The Nok terracotta depiction of a figure with a seashell on its head indicates that these riverine trade routes may have extended to the Atlantic coast.[36] Latter artistic traditions – Igbo-Ukwu and Ile Ife – may have been shaped by the clay terracotta tradition of the Nok culture.[37] Iron metallurgy may have been independently developed in the Nok culture between the 9th century BCE and 550 BCE.[29][30] As each share cultural and artistic similarity with the Nok culture, the Niger-Congo-speaking Yoruba, Jukun, or Dakakari peoples may be descendants of the Nok peoples.[38] Based on stylistic similarities with the Nok terracottas, the bronze figurines of the Yoruba Ife Empire and the Bini kingdom of Benin may also be continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.[39]

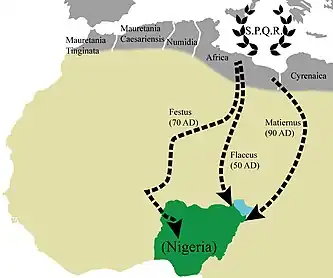

Roman expeditions to Nigeria (1st century AD)

Between 50 AD and 90 AD, Roman explorers undertook three expeditions to the area of present-day Nigeria. The reports of these expeditions confirm, among other things, the geologically already established extent of Lake Chad at that time and thus its drastic shrinkage in the past 2,000 years.

The expeditions were supported by legionaries and served mainly commercial purposes.[40]

One of the main goals of the explorations was the search for and extraction of gold, which was to be transported back to the Roman provinces on the Mediterranean coast by land with the help of camels.[41]

The Romans had at their disposal the memoirs of the ancient Carthaginian explorer Hanno the Navigator.[42] However, it is not known to what extent they were read, believed or found interesting by the Romans.

The three Roman explorations/expeditions in Nigeria were:

- The Flaccus expedition: Ptolemy wrote that Septimius Flaccus carried out his expedition in 50 AD (at the time of Emperor Claudius) to take revenge on the nomadic raiders who had attacked Leptis Magna and reached Sebha and the Aozou area.[43] He then reached the Bahr Erguig, Chari and Logone rivers in the Lake Chad area, which was called the "land of the Ethiopians" (or black men) and called Agisymba.

- The Matiernus expedition: Ptolemy wrote that Julius Maternus (or Matiernus) undertook a mainly commercial expedition around 90 AD (the time of Domitian). From the Gulf of Sirte, he arrived at the Central African Republic in a region then called Agisymba. He returned to Rome with a rhinoceros with two horns, which was exhibited in the Colosseum.[44]

- According to historians such as Susan Raven,[45] there was another Roman expedition to Central Africa, which may have reached northwestern Nigeria thanks to the Niger River.[46] Pliny wrote that in 70 AD. (in the time of Vespasian), a legatus legionis or commander of Legio III Augusta named Festus undertook an expedition in the direction of the Niger River. Festus went to the eastern Hoggar Mountains and eventually arrived in the area where Timbuktu is located today. It is possible that some of his legionnaires may have reached as far as the Niger River, and reached as far as the forests on the equator, navigating the river to its mouth in what is now Nigeria.

Roman coins have been found in Nigeria. However, it is likely that all these coins were introduced at a much later date and there was not direct Roman traffic this far down the west coast. The coins are the only ancient European items found in Central Africa.[47]

Early states before 1500

The early independent kingdoms and states that make up present-day state of Nigeria are (in alphabetical order): Benin Kingdom, Borgu Kingdom, Fulani Empire, Hausa Kingdoms, Kanem Bornu Empire, Kwararafa Kingdom, Ibibio Kingdom, Nri Kingdom, Nupe Kingdom, Oyo Empire, Songhai Empire, Warri Kingdom, Ile Ife Kingdom, and Yagba East Kingdom.

Oyo and Benin

During the 15th century, Oyo and Benin surpassed Ife as political and economic powers, although Ife preserved its status as a religious center. Respect for the priestly functions of the oni of Ife was a crucial factor in the evolution of Yoruba culture. The Ife model of government was adapted at Oyo, where a member of its ruling dynasty controlled several smaller city-states. A state council (the Oyo Mesi) named the Alaafin (king) and acted as a check on his authority. Their capital city was situated about 100 km north of present-day Oyo. Unlike the forest-bound Yoruba kingdoms, Oyo was in the savanna and drew its military strength from its cavalry forces, which established hegemony over the adjacent Nupe and the Borgu kingdoms and thereby developed trade routes farther to the north.

The Benin Empire (1440–1897; called Bini by locals) was a pre-colonial African state in what is now modern Nigeria. It should not be confused with the modern-day country called Benin, formerly called Dahomey.[48]

The Igala are an ethnic group of Nigeria. Their homeland, the former Igala Kingdom, is an approximately triangular area of about 14,000 km2 (5,400 sq mi) in the angle formed by the Benue and Niger rivers. The area was formerly the Igala Division of Kabba province, and is now part of Kogi State. The capital is Idah in Kogi state. Igala people are majorly found in Kogi state. They can be found in Idah, Igalamela/Odolu, Ajaka, Ofu, Olamaboro, Dekina, Bassa, Ankpa, omala, Lokoja, Ibaji, Ajaokuta, Lokoja and kotonkarfe Local government all in Kogi state. Other states where Igalas can be found are Anambra, Delta and Benue states.

The royal stool of Olu of warri was founded by an Igala prince.

Northern kingdoms of the Sahel

Trade is the key to the emergence of organized communities in the sahelian portions of Nigeria. Prehistoric inhabitants adjusting to the encroaching desert were widely scattered by the third millennium BC, when the desiccation of the Sahara began. Trans-Saharan trade routes linked the western Sudan with the Mediterranean since the time of Carthage and with the Upper Nile from a much earlier date, establishing avenues of communication and cultural influence that remained open until the end of the 19th century. By these same routes, Islam made its way south into West Africa after the 9th century.

By then a string of dynastic states, including the earliest Hausa states, stretched into western and central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and Kanem, which were not within the boundaries of modern Nigeria but which influenced the history of the Nigerian savanna. Ghana declined in the 11th century but was succeeded by the Mali Empire which consolidated much of western Sudan in the 13th century.

Following the breakup of Mali, a local leader named Sonni Ali (1464–1492) founded the Songhai Empire in the region of middle Niger and western Sudan and took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sonni Ali seized Timbuktu in 1468 and Djenné in 1473, building his regime on trade revenues and the cooperation of Muslim merchants. His successor Askia Muhammad Ture (1493–1528) made Islam the official religion, built mosques, and brought Muslim scholars, including al-Maghili (d.1504), the founder of an important tradition of Sudanic African Muslim scholarship, to Gao.[49]

Although these western empires had little political influence on the Nigerian savanna before 1500 they had a strong cultural and economic impact that became more pronounced in the 16th century, especially because these states became associated with the spread of Islam and trade. Throughout the 16th-century much of northern Nigeria paid homage to Songhai in the west or to Borno, a rival empire in the east.

The Golden Age

During the 14th and 16th centuries, the demand for gold increased due to European and Islamic states wanting to change their currencies to gold. This led to an increase in trans-Saharan Trade.[50]

Kanem–Bornu Empire

Borno's history is closely associated with Kanem, which had achieved imperial status in the Lake Chad basin by the 13th century. Kanem expanded westward to include the area that became Borno. The mai (king) of Kanem and his court accepted Islam in the 11th century, as the western empires also had done. Islam was used to reinforce the political and social structures of the state although many established customs were maintained. Women, for example, continued to exercise considerable political influence.[51]

The mai employed his mounted bodyguard and an inchoate army of nobles to extend Kanem's authority into Borno. By tradition, the territory was conferred on the heir to the throne to govern during his apprenticeship. In the 14th century, however, dynastic conflict forced the then-ruling group and its followers to relocate in Borno, as a result the Kanuri emerged as an ethnic group in the late 14th and 15th centuries. The civil war that disrupted Kanem in the second half of the 14th century resulted in the independence of Borno.[51]

Borno's prosperity depended on the trans-Sudanic slave trade and the desert trade in salt and livestock. The need to protect its commercial interests compelled Borno to intervene in Kanem, which continued to be a theatre of war throughout the 15th century and into the 16th century. Despite its relative political weakness in this period, Borno's court and mosques under the patronage of a line of scholarly kings earned fame as centres of Islamic culture and learning.[52]

Hausa Kingdoms

The Hausa Kingdoms began as seven states founded according to the Bayajidda legend by sons of Bawo, the son of the hero and the queen Magajiya Daurama[53]: Daura, Kano, Katsina, Zaria (Zazzau), Gobir, Rano, and Biram.

According to the Bayajidda legend, the Banza Bakwai states were founded by sons of Karbagari, the son of Bayajidda and the slave-maid, Bagwariya.[53] They are called the Bastard Seven on account of their ancestress' slave status:[53] Zamfara, Kebbi, Yauri, Gwari, Kwararafa, Nupe, and Ilorin.

Since the beginning of Hausa history, the seven states of Hausaland divided up production and labor activities in accordance with their location and natural resources. Kano and Rano were known as the "Chiefs of Indigo." Cotton grew readily in the great plains of these states, and they became the primary producers of cloth, weaving and dying it before sending it off in caravans to the other states within Hausaland and to extensive regions beyond. Biram was the original seat of government, while Zaria supplied labor and was known as the "Chief of Slaves." Katsina and Daura were the "Chiefs of the Market," as their geographical location accorded them direct access to the caravans coming across the desert from the north. Gobir, located in the west, was the "Chief of War" and was mainly responsible for protecting the empire from the invasive Kingdoms of Ghana and Songhai.[54] Islam arrived at Hausaland along the caravan routes. The famous Kano Chronicle records the conversion of Kano's ruling dynasty by clerics from Mali, demonstrating that the imperial influence of Mali extended far to the east. Acceptance of Islam was gradual and was often nominal in the countryside where folk religion continued to exert a strong influence. Nonetheless, Kano and Katsina, with their famous mosques and schools, came to participate fully in the cultural and intellectual life of the Islamic world.[55] The Fulani began to enter the Hausa country in the 13th century and by the 15th century, they were tending cattle, sheep, and goats in Borno as well. The Fulani came from the Senegal River valley, where their ancestors had developed a method of livestock management based on transhumance. Gradually they moved eastward, first into the centers of the Mali and Songhai empires and eventually into Hausaland and Borno. Some Fulbe converted to Islam as early as the 11th century and settled among the Hausa, from whom they became racially indistinguishable. There they constituted a devoutly religious, educated elite who made themselves indispensable to the Hausa kings as government advisers, Islamic judges, and teachers.[28]

The Hausa Kingdoms were first mentioned by Ya'qubi in the 9th century and they were by the 15th-century vibrant trading centers competing with Kanem–Bornu and the Mali Empire. The primary exports were slaves, leather, gold, cloth, salt, kola nuts, and henna. At various moments in their history, the Hausa managed to establish central control over their states, but such unity has always proven short. In the 11th-century, the conquests initiated by Gijimasu of Kano culminated in the birth of the first united Hausa Nation under Queen Amina, the Sultana of Zazzau but severe rivalries between the states led to periods of domination by major powers like the Songhai, Kanem and the Fulani.[56]

Despite relatively constant growth, the Hausa states were vulnerable to aggression and, although the vast majority of its inhabitants were Muslim by the 16th century, they were attacked by Fulani jihadists from 1804 to 1808. In 1808 the Hausa Nation was finally conquered by Usman dan Fodio and incorporated into the Hausa-Fulani Sokoto Caliphate.[57]

Yoruba

Historically, the Yoruba people have been the dominant group on the west bank of the Niger. Their nearest linguistic relatives are the Igala who live on the opposite side of the Niger's divergence from the Benue, and from whom they are believed to have split about 2,000 years ago. The Yoruba were organized in mostly patrilineal groups that occupied village communities and subsisted on agriculture. From approximately the 8th century, adjacent village compounds called ilé coalesced into numerous territorial city-states in which clan loyalties became subordinate to dynastic chieftains.[58] Urbanisation was accompanied by high levels of artistic achievement, particularly in terracotta and ivory sculpture and in the sophisticated metal casting produced at Ife.

The Yoruba are especially known for the Oyo Empire that dominated the region. The Oyo Empire held supremacy over other Yoruba nations like the Egba Kingdom, Awori Kingdom, and the Egbado. In its prime, they also dominated the Kingdom of Dahomey (now located in the modern day Republic of Benin).[59]

The Yoruba pay tribute to a pantheon composed of a Supreme Deity, Olorun and the Orisha.[60] The Olorun is now called God in the Yoruba language. There are 400 deities called Orisha who perform various tasks.[61] According to the Yoruba, Oduduwa is regarded as the ancestor of the Yoruba kings. According to one of the various myths about him, he founded Ife and dispatched his sons and daughters to establish similar kingdoms in other parts of what is today known as Yorubaland. The Yorubaland now consists of different tribes from different states which are located in the Southwestern part of the country, states like Lagos State, Oyo State, Ondo State, Osun State, Ekiti State and Ogun State, among others.[62]

Igbo Kingdoms

Nri Kingdom

The Kingdom of Nri is considered to be the foundation of Igbo culture and the oldest Kingdom in Nigeria.[63] Nri and Aguleri, where the Igbo creation myth originates, are in the territory of the Umueri clan, who trace their lineages back to the patriarchal king-figure, Eri.[64] Eri's origins are unclear, though he has been described as a "sky being" sent by Chukwu (God).[64][65] He has been characterized as having first given societal order to the people of Anambra.[65]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Nri hegemony in Igboland may go back as far as the 9th century,[66] and royal burials have been unearthed dating to at least the 10th century. Eri, the god-like founder of Nri, is believed to have settled in the region around 948 with other related Igbo cultures following in the 13th century.[67] The first Eze Nri (King of Nri), Ìfikuánim, followed directly after him. According to Igbo oral tradition, his reign started in 1043.[68] At least one historian puts Ìfikuánim's reign much later, around 1225.[69]

Each king traces his origin back to the founding ancestor, Eri. Each king is a ritual reproduction of Eri. The initiation rite of a new king shows that the ritual process of becoming Ezenri (Nri priest-king) follows closely the path traced by the hero in establishing the Nri kingdom.

— E. Elochukwu Uzukwu[65]

Nri and Aguleri and part of the Umueri clan, a cluster of Igbo village groups which traces its origins to a sky being called Eri and significantly, includes (from the viewpoint of its Igbo members) the neighbouring kingdom of Igala.

— Elizabeth Allo Isichei[70]

The Kingdom of Nri was a religio-polity, a sort of theocratic state, that developed in the central heartland of the Igbo region.[67] The Nri had a taboo symbolic code with six types. These included human (such as the birth of twins),[71] animal (such as killing or eating of pythons),[72] object, temporal, behavioral, speech and place taboos.[73] The rules regarding these taboos were used to educate and govern Nri's subjects. This meant that, while certain Igbo may have lived under different formal administrations, all followers of the Igbo religion had to abide by the rules of the faith and obey its representative on earth, the Eze Nri.[72][73]

With the decline of Nri kingdom in the 15th to 17th centuries, several states once under their influence, became powerful economic oracular oligarchies and large commercial states that dominated Igboland. The neighboring Awka city-state rose in power as a result of their powerful Agbala oracle and metalworking expertise. The Onitsha Kingdom, which was originally inhabited by Igbos from east of the Niger, was founded in the 16th century by migrants from Anioma (Western Igboland). Later groups like the Igala traders from the hinterland settled in Onitsha in the 18th century. Kingdoms west of the River Niger like Aboh (Abo), which was significantly populated by Igbos among other tribes, dominated trade along the lower River Niger area from the 17th century until European explorations into the Niger delta. The Umunoha state in the Owerri area used the Igwe ka Ala oracle at their advantage. However, the Cross River Igbo state like the Aro had the greatest influence in Igboland and adjacent areas after the decline of Nri.[74][75]

The Arochukwu kingdom emerged after the Aro-Ibibio Wars from 1630 to 1720, and went on to form the Aro Confederacy which economically dominated Eastern Nigerian hinterland. The source of the Aro Confederacy's economic dominance was based on the judicial oracle of Ibini Ukpabi ("Long Juju") and their military forces which included powerful allies such as Ohafia, Abam, Ezza, and other related neighboring states. The Abiriba and Aro are Brothers whose migration is traced to the Ekpa Kingdom, East of Cross River, their exact take of location was at Ekpa (Mkpa) east of the Cross River. They crossed the river to Urupkam (Usukpam) west of the Cross River and founded two settlements: Ena Uda and Ena Ofia in present-day Erai. Aro and Abiriba cooperated to become a powerful economic force.[76]

Igbo gods, like those of the Yoruba, were numerous, but their relationship to one another and human beings was essentially egalitarian, reflecting Igbo society as a whole. A number of oracles and local cults attracted devotees while the central deity, the earth mother and fertility figure Ala, was venerated at shrines throughout Igboland.

The weakness of a popular theory that Igbos were stateless rests on the paucity of historical evidence of pre-colonial Igbo society. There is a huge gap between the archaeological finds of Igbo Ukwu, which reveal a rich material culture in the heart of the Igbo region in the 8th century, and the oral traditions of the 20th century. Benin exercised considerable influence on the western Igbo, who adopted many of the political structures familiar to the Yoruba-Benin region, but Asaba and its immediate neighbours, such as Ibusa, Ogwashi-Ukwu, Okpanam, Issele-Azagba and Issele-Ukwu, were much closer to the Kingdom of Nri. Ofega was the queen for the Onitsha Igbo.

Akwa Akpa

The modern city of Calabar was founded in 1786 by Efik families who had left Creek Town, farther up the Calabar river, settling on the east bank in a position where they were able to dominate traffic with European vessels that anchored in the river, and soon becoming the most powerful in the region extending from now Calabar down to Bakkasi in the East and Oron Nation in the West.[77] Akwa Akpa (named Calabar by the Spanish) became a center of the Atlantic slave trade, where African slaves were sold in exchange for European manufactured goods.[78] Igbo people formed the majority of enslaved Africans sold as slaves from Calabar, despite forming a minority among the ethnic groups in the region.[79] From 1725 until 1750, roughly 17,000 enslaved Africans were sold from Calabar to European slave traders; from 1772 to 1775, the number soared to over 62,000.[80]

With the suppression of the slave trade,[81] palm oil and palm kernels became the main exports. The chiefs of Akwa Akpa placed themselves under British protection in 1884.[82] From 1884 until 1906 Old Calabar was the headquarters of the Niger Coast Protectorate, after which Lagos became the main center.[82] Now called Calabar, the city remained an important port shipping ivory, timber, beeswax, and palm produce until 1916, when the railway terminus was opened at Port Harcourt, 145 km to the west.[83]

First contact with colonial powers, Nigeria as a "slave coast"

Trade in ivory, gold and slaves

.jpg.webp)

The first encounters between the inhabitants of the coast and a European power, the Portuguese, took place around 1485. The Portuguese began to trade extensively, particularly with the kingdom of Benin. The Portuguese traded European products, especially weapons, for ivory and palm oil and increasingly for slaves. The manillas that the Portuguese used to pay their Nigerian suppliers were melted down again in the Kingdom of Benin to create the bronze artworks that adorned the royal palace as a sign of affluence.[84]

In 1553, the first English expedition arrived in Benin. From then on, European merchant ships regularly anchored on the West African coast, albeit at a safe distance from the mainland due to the mosquitoes in the lagoons and the tropical diseases they spread. Locals came to these ships on barques and conducted their business.[85] The Europeans named the coasts of West Africa after the products that were of interest to them there. The "Ivory Coast" still exists today. The western coast of Nigeria became the slave coast. In contrast to the Gold Coast further west (today's Ghana), the European powers did not establish any fortified bases here until the middle of the 19th century.

The harbour of Calabar on the historic Bay of Biafra became one of the largest slave trading centres in West Africa. Other important slave harbours in Nigeria were located in Badagry, Lagos in the Bay of Benin and Bonny Island.[85][86] Most of the enslaved people brought to these harbours were captured in raids and wars.[87] The most "prolific" slave-trading kingdoms were the Edo Empire of Benin in the south, the Oyo Empire in the south-west and the Aro Confederacy in the south-east.[85][86]

Caliphate of Sokoto (1804 to 1903)

.png.webp)

In the north, the incessant fighting between the Hausa city-states and the decline of the Bornu Empire led to the Fulani gaining a foothold in the region. Originally, the Fulani mainly travelled with cattle through the semi-desert region of Sahel in northern Sudan, avoiding trade and mixing with the Sudanese peoples. At the beginning of the 19th century, Usman dan Fodio led a successful jihad against the Hausa kingdoms and founded the centralised caliphate of Sokoto. The empire, with Arabic as its official language, grew rapidly under his rule and that of his descendants, who sent invading armies in all directions. The vast landlocked empire linked the east with western Sudan and penetrated the south, conquering parts of the Oyo kingdom and advancing into the Yoruba heartland of Ibadan. The territory controlled by the empire included much of what is now northern and central Nigeria. The Sultan sent emirs to establish suzerainty over the conquered territories and to promote Islamic civilisation; the emirs in turn grew richer and more powerful through trade and slavery.

By the 1890s, the largest slave population in the world, about two million, was concentrated in the Sokoto Caliphate. Slaves were used on a large scale, especially in agriculture.[88] When the Sokoto Caliphate disintegrated into various European colonies in 1903, it was one of the largest pre-colonial African states.[89]

Expeditions along the Niger and in northern Nigeria

Around 1829, Hugh Clapperton's expedition to Europe made it known that and where the Niger flows into the Atlantic. (He himself did not survive the journey, but died of malaria and dysentery. His documents were published by his servant Richard Lander). After this, there were numerous privately funded forays into the interior, such as the Niger Expedition of 1841 (in which a large number of the European participants quickly died of tropical diseases and which is reported in the diary of fellow traveller Samuel Ajayi Crowther, mentioned again in the next chapter).[90][91]

Around 1850, the explorer Heinrich Barth travelled through northern Nigeria as part of a British expedition. Through his travels, Barth acquired special merits in the unprejudiced and respectful study of peoples and languages (he himself had the ability to learn African languages very quickly - he spoke and wrote Arabic fluently), as well as in African history. Barth also developed the hypothesis of a primeval wet phase in northern Africa.

British ban on the slave trade (from 1807)

Around 1750, British merchant ships shipped European goods to Africa, from there slaves to American plantations and products from there, such as tobacco, to Europe. However, from 1787 and increasingly from 1791, following reports of a slave revolt in Saint Domingue, the British Parliament debated the abolition of the slave trade.[92]

With the prohibition of the slave trade (not slavery) by Britain in 1807, British interest in Nigeria shifted to palm oil for use in soaps and as a lubricant for machinery. However, abolition in Britain was one-sided, and many other countries took its place.[93] European companies and smugglers continued to operate the Atlantic slave trade. The British West Africa Squadron attempted to intercept the smugglers at sea. The rescued slaves were taken to Freetown, a colony in West Africa originally founded by Lieutenant John Clarkson for the resettlement of slaves freed by Britain after the American Revolutionary War in North America.

British colonial rule

Crown Colony of Lagos (since 1861)

Britain's West Africa squadron was tenacious in concluding anti-slavery treaties with coastal chiefdoms along the West African coast from Sierra Leone through the Niger Delta to the south of the Congo.[94] However, the Nigerian coast proved difficult to control with its countless bays, meandering channels and rampant tropical diseases.[95] Badagry, Lagos, Bonny and Calabar therefore remained lively centres of the slave trade. The fight against the slave trade by the British plunged the kingdom of Oyo into a crisis that ultimately led to civil war within the Yoruba region. It became a constant source of prisoners of war for the slave markets.

In 1841, Oba Akitoye ascended the throne of Lagos and tried to put an end to the slave trade. Some Lagos merchants resisted the ban, deposed the king and replaced him with his brother Kosoko.[95] Britain intervened in this power struggle within the Lagos royalty by bombarding Lagos with the Royal Navy in 1851. The British thus replaced Kosoko with Akitoye again. In 1852, Akitoye and the British consul John Beecroft signed a treaty to free the slaves and grant the British permanent trade access to Lagos. However, Akitoye had difficulties implementing these resolutions. The situation therefore remained unsatisfactory for Britain.

The Royal Navy originally used the harbour of the island of Fernando Po (now Bioko, Equatorial Guinea) off Nigeria as a base of operations. In 1855, Spain claimed this harbour for itself. The Royal Navy therefore had to find another naval base.[95] King Akitoye had died in the meantime. His brother Kosoko then threatened to take back control of Lagos with the help of French colonial troops. The American Civil War, which centred on the issue of slavery, made the power struggle for Lagos particularly urgent. As a result, Lord Palmerston (British Prime Minister) made the decision that it was expedient "losing no time in assuming the formal protectorate of Lagos".[94] William McCoskry, the acting consul in Lagos, together with Commander Bedingfield, convened a meeting with King Dosunmu, Akitoye's successor, on board HMS Prometheus on 30 July 1861, at which the British intentions were explained. Dosunmu resisted the terms of the treaty, but under the threat of having Commander Bedingfield bombard Lagos, he relented and signed the Lagos Cession Treaty.[96]

Lagos proved to be strategically useful and became a major trading centre as traders could count on the protection of the Royal Navy to protect them from pirates, for example.[95] British missionaries penetrated further inland. In 1864, Samuel Ajayi Crowther became the first African bishop of the Anglican Church.[97]

After its experiences in the American War of Independence, Great Britain had limited itself to maintaining strategically placed bases around the world - such as Lagos - and avoided colonising regions far from the coast. This changed in the 1860s, when European powers embarked on the "Scramble for Africa". Up until this point, European trade with the natives was conducted by ships that anchored off the coast and travelled on once the business was concluded. As tropical lagoons - unlike the open sea - offer favourable conditions for mosquitoes, which pass on tropical diseases, Europeans avoided going ashore. Because of the "sleeping sickness", West Africa was nicknamed "The white man's grave" until around 1850. The industrial production of quinine from the 1820s and its use as a prophylactic against malaria on a large scale changed the situation. The European naval powers were now able to establish permanent settlements in the tropics.

The Royal Niger Company, the monopolist on the Niger

The first years of European colonialism in Africa were characterised by the Austrian school of economics and the marginal utility theory it advocated, according to which the value of products manufactured in Europe was higher in markets that were not yet saturated, such as Africa (marginal utility), and trade with colonies was therefore more profitable than in one's own country, for example. (The lower demand or purchasing power in the unsaturated market was not taken into account).

With the prospect of such high profits, various private trading companies promoted European influence in West Africa. One of them was the United Africa Company, founded by George Goldie in 1879, which was granted concessions for the entire area around the Niger Basin by the British government in 1886 under the name Royal Niger Company. The RNC marked out its territory as if it were a state in its own right and also negotiated treaties with the northern states, the Sokoto Caliphate, Nupe and Gwandu.

The RNC faced competition from three other groups, two French trading companies and another British group. A price war ensued, in which the RNC emerged victorious because in France the main proponent of African colonisation, Léon Gambetta, had died in 1882 and in 1883 considerable subsidies for these "colonisation companies" were cancelled by the mother country.[98]

The RNC's monopoly enabled Britain to resist French and German demands for the internationalisation of trade on the Niger during negotiations at the Berlin Conference in 1884-1885. Goldie succeeded in having the region in which the RNC operated included in the British sphere of interest. British assurances that free trade in Niger would be respected were hollow words: the RNC's more than 400 contracts with local leaders obliged the natives to trade exclusively with or through the company's agents. High tariffs and royalties drove competing companies out of the territory.[99] When King Jaja of Opobo organised his own trading network and even began routing his own palm oil shipments to Britain, he was lured onto a British warship and exiled to St Vincent on charges of 'breach of treaty' and 'obstruction of trade'.[100]

After the Berlin Congo Conference

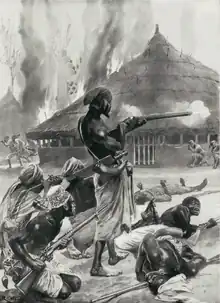

The punitive expedition to the Kingdom of Benin in 1897

Benin was a slave-owning state 150 kilometres east of Lagos and was one of the four largest kingdoms in what is now Nigeria. As early as 1862, there were reports of human sacrifices being made in Benin in times of need. Consul Burton described the kingdom as "gratuitous barbarity which stinks of death".[101]

In 1892, Great Britain concluded a contract with King (Oba) Ovọnramwẹn of Benin for the supply of palm oil. The latter signed reluctantly and shortly afterwards made additional financial demands. In 1896, Vice-Consul Phillips travelled to Ovọnramwẹn with 18 officials, 180 porters and 60 local workers to renegotiate the contract. He sent a delegate ahead with gifts to announce his visit - but the king sent word that he did not wish to receive the visit for the time being[102] (King Ovọnramwẹn was aware of the fate of King Jaja of Opobo (see above), which could explain his lack of hospitality). Phillips nevertheless set off, but was ambushed, from which only two of his fellow travellers escaped alive, albeit seriously injured.[102]

In February 1897, a punitive expedition was set up under Admiral Rawson. The Colonial Office in London ruled: "It is imperative that a most severe lesson be given the Kings, Chiefs, and JuJu men of all surrounding countries, that white men cannot be killed with impunity..."[101] 5,000 British soldiers and sailors invaded the Kingdom of Benin, which barely defended itself but made the above-mentioned human sacrifices in its misery. The British forces encountered shocking scenes.[103]

The Kingdom of Benin was incorporated into the British dominion. The British burnt down the royal palace of Benin and looted the bronze sculptures there, which are now a World Heritage Site. These were later auctioned off in Europe to finance the punitive expedition.

For the next ten years, the British would expand their dominion primarily through military conquest rather than trade relations.

The West African Frontier Force

.jpg.webp)

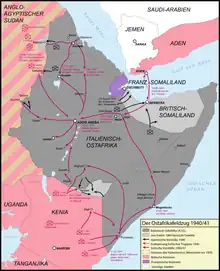

In 1897, Colonel Lugard, who had already established and stabilised British colonial rule in Malawi and Uganda, was commissioned to set up an indigenous Nigerian force to protect British interests in the hinterland of the colony of Lagos and Nigeria against French attacks. In August 1897, Lugard organised the West African Frontier Force and commanded it until the end of December 1899. By September 1898, Britain and France had already settled their colonial disputes in the Fashoda Crisis and concluded the Entente cordiale in 1904, thus depriving the WAFF of its original purpose[104] (However, the WAFF was to play a crucial role in the liberation of East Africa from (fascist) Italian rule during the Second World War in 1941. Colonel Lugard would significantly determine Nigeria's development over the next 22 years.

First railway line

The first railway line in West and Central Africa - between Lagos and Abeokuta - was opened in Nigeria in 1898[105] (However, it was followed shortly afterwards by the British colony of Gold Coast/Ghana (1901), the German colonies of Cameroon (1901) and Togo (1905) and the French colonies of Dahomey (1906) and Ivory Coast (1907)). Forced labour was also (or mainly) used in the construction work.[106] The staff of the railway company soon organised themselves and organised Nigeria's first strike in 1904.[107]

Southern Nigeria (since 1900)

The Royal Niger Company sells its land

Ten years after the "Scramble for Africa" - in the 1890s - it became increasingly clear that colonial rule in Africa was not a profitable endeavour and that the exploration and development of the continent, which had originally been initiated by the private sector, could only be continued through state-military measures and/or taxpayers' money. The above-mentioned marginal utility theory had given way to the theory of "shrinking markets", a term coined by the economic theorist Werner Sombart. According to this theory, colonies were supposedly a necessary measure for industrialised countries to maintain sales and food supplies. The theory was adopted by both "left-wing" theorists such as Bukharin and Luxemburg ("exploitation" of the colonies) and "right-wing" thinkers such as Rosenberg and Hitler ("Lebensraum").[108][109] The RNC's concession was revoked in 1899,[110] and on 1 January 1900 it ceded its territories to the British government for the sum of £865,000. The ceded territory was merged with the small Niger Coast Protectorate, which had been under British control since 1884, to form the Southern Nigeria Protectorate,[111] and the remaining RNC territory of around 1.3 million square kilometres became the Northern Nigeria Protectorate. 1,000 British soldiers were stationed in the Protectorate of Southern Nigeria, 2,500 in the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria and 700 in Lagos. The RNC was taken over by Lever Brothers in 1920 and became part of the Unilever Group in 1929. In 1939, the latter still controlled 80 per cent of Nigerian exports, mainly cocoa, palm oil and rubber.[112]

The south-east

Due to the complex coastline in the Niger Delta, there were no closed dominions in south-east Nigeria until 1900, but rather a conglomerate of city-states that focussed on trade along the coast and inland along the Niger and Benue rivers. These city-states, which were united in the "Aro Confederacy", had a religious centre in Arochukwu, the "Juju Oracle". The form of decision-making in the city-states can be described as "pre-democratic". In this region, which later became sadly known as "Biafra", feudal rule was just as difficult to enforce as British colonial rule. (The later Biafra War of 1966 to 1970 was, among other things, a conflict between the democratic instincts of the south-eastern Igbo population and the authoritarian structures in the rest of Nigeria). The British defeated the Aro Confederacy in the Anglo-Aro War (1901-1902) and spread their influence along the coast to the south-east as far as German Cameroon. However, control of the Niger Delta remained an unsolved problem both for the British colonial rulers and later for independent Nigeria. Pirates, marauders, self-proclaimed freedom fighters and (since 1957) oil thieves still find enough nooks and crannies in the confusing landscape and under the jungle canopy to evade police action.

After 1902

In 1906, the crown colony of Lagos was incorporated into the protectorate of Southern Nigeria.

In Lekki, near Lagos, the Nigerian Bitumen Corporation under businessman John Simon Bergheim discovered crude oil during test drilling in 1908. However, engineers were unable to prevent large quantities of water from being extracted as well. Oil production could therefore not be made profitable without additional investment. Bergheim's fatal car accident in 1912 put an end to further exploration of Nigeria's oil reserves for the time being.[113]

In 1909, coal deposits were discovered and extracted in the south-east of Nigeria, in Enugu[114] Two years later, this region, the Nti Kingdom, was placed directly under British colonial administration.[115][116]

Despite the consecration of Samuel Ajayi Crowther as a bishop - or perhaps because of it - European and North American churches refused to accept dark-skinned clergymen, while the mainly Protestant missionary work in southern Nigeria was quite successful. This led to countless evangelistic and Pentecostal free churches, which are still omnipresent in the south today.[117]

Nigeria's first trade union, the Nigeria Civil Service Union, was formed in 1912,[118] but would not be recognised until 1938, until which time its members were subjected to harassment.

Northern Nigeria (since 1900)

In 1900, Colonel Lugard was appointed High Commissioner of the newly created Protectorate of Northern Nigeria. He read the proclamation at Mount Patti in Lokoja that established the protectorate on 1 January 1900,[119] but at this time the part of northern Nigeria that was actually under British control was still small.[104]

North-east

In 1893, Rabih az-Zubayr, a Sudanese warlord, conquered the Kingdom of Bornu. The British recognised Rabih as "Sultan of Borno" until the French killed Rabih at the Battle of Kousséri on 22 April 1900. The colonial powers of Great Britain, France and Germany divided up his territory, with the British receiving what is now north-east Nigeria. They formally restituted the Borno Empire under British rule before the conquest in 1893 and appointed a scion of the ruling family of the time, Abubakar Garbai, as "Shehu" (Sheikh).

Northwest

In 1902, the British advanced north-westwards into the Sokoto Caliphate. In 1903, victory at the Battle of Kano gave the British a logistical advantage in pacifying the heartland of the Sokoto Caliphate and parts of the former Borno Empire. On 13 March 1903, the last vizier of the caliphate surrendered. By 1906, resistance to British rule had ended,[120] and there would be no more war within Nigeria's borders for the next 60 years. When Lugard resigned as commissioner in 1906, the entire region of present-day Nigeria was administered under British supervision.[104]

Unification into "Crown Colony and Protectorate" 1914, Governor Lugard

.svg.png.webp)

In 1912, after an interlude in Hong Kong, Lugard returned as governor of the two Nigerian protectorates. He merged the two colonies into one.[104]

In the same year, Lugard, who found the inhabitants of Lagos rebellious, had a new seaport built in the south-east as a rival to Lagos and named it Port Harcourt after his superior in the Colonial Office. This seaport soon received a railway line to Enugu and shipped the coal mined there (from 1958 also crude oil) overseas.

Unification and yet separation

Lugard became the first governor of All Nigeria. The unification of Nigeria helped to give Nigeria common telegraphs, railways, customs and excise duties, a Supreme Court,[121] uniform time,[122] a common currency[123] and a common civil service.[124] Lugard thus introduced what was needed for the infrastructure of a modern state. However, the north and south remained as two separate countries with separate administrations.[125]

English was the official language in the south and Hausa in the north.[126]

The protectorate in the south financed itself with £1,933,235 in tax revenue (1912). The larger but underdeveloped Northern Protectorate collected £274,989 in the same year and had to be subsidised by the British to the tune of £250,000 annually.[126] (This economic structure basically exists to this day.)

Regional differences in access to modern education soon became pronounced. Some children of the southern elite went to Britain for higher education. The imbalance between North and South was also reflected in Nigeria's political life. For example, slavery was not banned in northern Nigeria until 1936, while it was abolished in other parts of Nigeria around 1885.[127] Northern Nigeria still had between 1 million and 2.5 million slaves around 1900.[128]

"Indirect Rule" - colonial rule while preserving social structures

Lugard was a master of efficient power structures. He was the inventor, theoretical pioneer and chief practitioner of "Indirect Rule", according to which the existing power structures, laws and traditions in colonies were left largely intact and integrated into the colonial system. (Indirect rule was practised by the British in protectorates and by the German colonial system, while the French, Belgians and Portuguese, for example, dismantled the pre-colonial structures and replaced them with direct colonial administration). In doing so, Lugard relied on the existing traditional power structures, or what he thought they were. The emirs of the north retained their hereditary titles and functions, dispensed justice according to Sharia law, had the police power to implement this law, collected taxes for the British and ultimately implemented British directives. In return, the British supported their power.[129] Thus, the feudal power structures in northern Nigeria were preserved and subsidised for decades.

The attempt to enforce this system in the south also met with varying degrees of success. In the Yoruba region of the south-west, the British were able to tie in with existing or formerly existing kingdoms and their borders. However, as there were no hierarchical or even feudal structures in the south-east through which the British could indirectly rule, they appointed "Warrant Chiefs" with powers to act as local representatives of the British administration among their people. However, the British did not realise that in some parts of Africa the concept of "chiefs" or "kings" was not known. Among the Igbo, for example, decisions were made through lengthy debates and general consensus. The new powers vested in the Warrant Chiefs and reinforced by the native court system led to an exercise of power and authority unprecedented in pre-colonial times. The Warrant Chiefs also used their power to amass wealth at the expense of their subjects. The Warrant Chiefs were corrupt, arrogant and accordingly hated.[130][131]

Racial approaches in the army

From the outset, British colonial rule utilised - and reinforced - the differences between the ethnic groups present in order to offer itself to each side as a power-preserving factor and to be able to control the oversized colony with relatively little military expenditure (4,200 British soldiers). In the south, education, economy and civilisational achievements dominated, while in the north the military, feudalism and Islamic traditions[132] were deliberately reinforced by the British. While officer positions were filled with British, enlisted men, non-commissioned officers and higher non-commissioned officer positions (sergeant majors) were exclusively filled with northern Nigerians, as these were regarded as "warrior peoples" in accordance with a popular doctrine practised in India since 1857 (e.g. Sikhs, Brahmins).[133] Nigeria thus remained divided in many respects into the northern and southern protectorates and the colony of Lagos.[134]

On Lugard, historian K. B. C. Onwubiko says: "His system of Indirect Rule, his hostility towards educated Nigerians in the South, and his system of education for the North which aimed at training only the sons of the chiefs and emirs as clerks and interpreters show him as one of Britain's arch-imperialists".[135]

First World War

In August 1914, a British-Nigerian military unit attacked Cameroon. After 18 months, the German Imperial Schutztruppe surrendered to a superior force of British, Nigerians, Belgians and French. Some German units were able to escape to the Spanish and thus neutral Rio Muni (today's Equatorial Guinea).

Time between the world wars

In the Treaty of Versailles, the German colony of Cameroon was divided up between the British and French as a League of Nations trust territory. In 1920, the western part of the former German colony of Cameroon was administratively annexed to British Nigeria as a League of Nations mandate territory under the name British Cameroons.[136]

Until the 1950s, contact between the colony of Nigeria and Great Britain was mainly maintained by mail ships. Once a month, a mail steamer of the Elder Dempster & Company from Liverpool docked in the capital Lagos/Apapa and in Calabar. These were alternately the MS Apapa and its sister ship, the MS Accra.[137] In addition to letters, parcels and newspapers, they also transported cargo and around 100 passengers and also made stops in Gambia, Sierra Leone, Liberia and the Gold Coast (Ghana)[138] In this way, colonial officials, officers of the colonial army, business travellers and globetrotters reached the West African colonies of the Commonwealth or their homes. The journey from Liverpool to Nigeria (Lagos/Apapa or Calabar) took about 14 days.

Governor Clifford, the Clifford Constitution

Lugard's successor (1919-1925), Sir Hugh Clifford, was an avowed opponent of Lugard's views and saw his role not in the efficient running of an apparatus of power, but in the development of the country. He intensified educational efforts in the south and repeatedly suggested to the Colonial Office in London that the power of the absolutist emirs ruling in the north should be limited - which was rejected. This further deepened the de facto division of the country into a northern, south-western and south-eastern part. In the north, the indirect rule aimed at preserving feudal rule continued to apply. In the south, an educated elite based on the European model emerged.[117] The railway company paid very well due to the activities of the well-organised railway workers' union, but also due to competing employers - who were happy to poach skilled workers. High school graduates could train as train drivers or technicians ("engineers") in six-year vocational school courses run by Nigerian Railways. During this training, the "apprentices" were paid and received an annual salary of £380 - £480 (as of 1935, in today's money value about £38 - 48,000, significantly more than the average Nigerian income today).[105] For the vocational students in Lagos, the railway company had specially provided a discarded but still functional 0-6-0 steam locomotive worth £4 million (in today's money value), which they could use to learn how it worked.[105]

In 1922, Clifford established the Legislative Council. The four elected members were from Lagos (3) and Calabar (1). The Legislative Council enacted laws for the colony and the protectorate of Southern Nigeria. It also approved the annual budget for the entire country. The four elected members were the first Africans to be elected to a parliamentary body in British West Africa. The Clifford Constitution accordingly led to the formation of political parties in Nigeria. Herbert Macaulay, a newspaper owner and grandson of Samuel Ajayi Crowther (see above), founded the first Nigerian political party - the Nigeria National Democratic Party - in 1923. It remained the strongest party in the elections until 1939.

1925 to 1929, "Women's War"

In the meantime, it had become clear that colonies were neither "profitable" in the sense of the marginal utility theory described above, nor were they the solution to the problem of shrinking markets. Instead, Nigeria continued to gobble up taxpayers' money despite investments totalling several billions (like most African colonies) and hardly benefited the economy of the mother country. The new governor Graeme Thomson therefore introduced harsh austerity measures in 1925, including massive redundancies and the introduction of direct taxation.

The planned tax on women market traders, Graeme Thomson's undiplomatic manner and the unpopular Warrant Chief system (see above) led to the "Women's War" of 1929 among the Igbo. The women farmers destroyed ten native courts by December 1929, when the troops restored order in the region. In addition, the houses of chiefs and employees of the native courts were attacked, European factories looted, prisons attacked and prisoners released. The women demanded the removal of the Warrant Chiefs and their replacement by native clan chiefs appointed by the people and not by the British. 55 women were killed by the colonial troops. Nevertheless, the Women's War of 1929 led to fundamental reforms in the British colonial administration. The British abolished the system of "Warrant Chiefs" and reviewed the nature of colonial rule over the natives of Nigeria. Several colonial administrators condemned the prevailing administrative system and agreed to the call for urgent reforms based on the indigenous system. In place of the old Warrant Chief system, tribunals were introduced that took into account the indigenous system of government that had prevailed before colonial rule.[139][140]

1930 to 1939

In 1933, the Lagos Youth Movement - later the Nigerian Youth Movement - was founded[139] and took a more strident stance in favour of independence than the NNDP. In 1938, the NYM called for Nigeria to be granted British Dominion status, putting it on a par with Australia or Canada.[117] In 1937, it was joined by Nnamdi Azikiwe, who had been exiled from Ghana/Gold Coast for seditious activities and who became publisher and editor-in-chief of the West African Pilot and father of Nigerian popular journalism. In 1938, the NYM protested against the cocoa cartel, which kept the purchase prices from farmers artificially low.[112] In 1939, the NYM became the strongest party in the elections in Lagos and Calabar (no elections were held elsewhere).

In 1934, the Warrant Chiefs were abolished.[141]

In 1935, the railway network reached its maximum expansion after the last investment projects were completed. It comprised 2,851 km of track with a gauge of 106.7 cm ("Cape gauge") and 214 km with a gauge of 76.2 cm. This made the Nigerian railway network the longest and most complex in West and Central Africa. In 1916, a 550 m long railway bridge over the Niger River and in 1934 a bridge over the Benue River connected the regional railway networks.[105] 179 mainline and 54 shunting locomotives were in use in 1934. Two maintenance and repair workshops in Lagos and Enugu employed about 2,000 locals.[105] Rail transport was efficiently synchronised with maritime traffic. Travellers from mail steamers could board the "Boat Express" waiting right next to it at the port of Apapa in Lagos and reach Kano in the far north of Nigeria within 43 hours in sleeping and dining cars.[105]

In 1931, the influential Nigerian Union of Teachers was founded under its president O. R. Kuti (the father of Fela Kuti).[141] Nigeria's first industrial union, the railway workers' union, was also founded in 1931 by lathe operator Michael Imoudu.[142] In 1939, trade unions were permitted by decree by the colonial administration, but Imoudu was arrested in 1943. The railway workers' union was considered the most militant workers' union in Nigeria. Imoudu remained under house arrest until 1945.[143]

Governor Cameron standardised the administration of the Northern and Southern Provinces in the 1930s by introducing a native appellate court system, High Courts and Magistrate Courts.

Second World War

Sinking of both mail ships to Nigeria

On 26 July 1940, one of the two mail ships connecting Nigeria with the colonial power, the MS Accra, was sunk off Ireland by the U-34 submarine. 24 people died.

On 15 November 1940, the sister ship on the same route, the MS Apapa, was sunk by a German FW 200 Condor on its way home off Ireland. 26 people lost their lives.[144] An identical ship was given the same name and took over the same route service (see picture above).[145]

Operation Postmaster

In 1942, Nigeria played a role in "Operation Postmaster". In an adventurous manner, British special agents from Lagos captured Italian and German supply ships for submarines in the South Atlantic on the nearby but Spanish and therefore neutral island of Bioko and brought them to the home port of Lagos.[146] The incident - in which no shots were fired - almost led to Franco's Spain entering the war alongside the Third Reich and fascist Italy.

Rationing, price control, agricultural damage, education offensive

As early as 1939, the Nigeria Supply Board was set up to promote the production of rubber and palm oil, which were considered important for the war effort, at the expense of food production. The import of agricultural products was restricted.

From 1942, farmers were only allowed to sell rice, maize, beans etc. to government agencies and at a very low price under the "Pullen Scheme" so that the British Isles, which were cut off from the continent, could be supplied with food at low cost. However, this price control motivated farmers to either not sell their products at all or to sell them on the black market. Others may have resorted to growing unregulated, i.e. inedible, produce. Nigeria's agriculture, which had already suffered from the European purchasing cartels (especially Unilever) and the Great Depression, was once again hampered in its development.[147] In December 1942, consumer goods were rationed. (Rationing would last until 1948.)[148] The transport of rice from Abeokuta to nearby Lagos was criminalised.

As a "positive" effect of the Second World War, the colonial administration trained war-critical skilled labour such as technicians, electricians, nurses, carpenters and clerks on a large scale during this period. New harbours and - for the first time - airports were built.[149]

Nigeria regiments, advance in Ethiopia

Throughout the war, 45,000 Nigerian soldiers served in the British forces in Africa and South East Asia. Nigerian regiments formed the majority of the British Army's 81st and 82nd West African Divisions.[150] These divisions fought in Palestine, Morocco, Sicily and Burma. Nigerian soldiers also fought in India.

Three battalions of the Nigeria Regiment fought in the Ethiopian campaign against fascist Italy. On 26 March 1941, two motorised companies of the Nigeria Regiment advanced 930 km from Kenya to Daghabur within 10 days in Mussolini-controlled Ethiopia. On 26 March, the Nigeria Regiment captured Harar near Djibouti after an advance of 1,600 km in 32 days. At the time, this was the fastest military advance in world history.[151] The advance also divided the fascist sphere of control in East Africa. In their hasty retreat, the Italian forces also left behind important ammunition and food depots. Addis Ababa was conquered by the Allies on 6 April.[152] The Ethiopian campaign became the Allies' first major success against the Axis powers, not least due to the "Blitzkrieg" of the Nigeria regiment.[151] With East Africa (1.9 million km2), Italy lost an area in a few days that was larger than today's Poland, Belarus, Ukraine and the Baltic states combined (1.3 million km2).

Ideas from India on independence

Fighting for the Allies were 600,000 volunteers from Africa, who had been promised equal brotherhood in arms with their Caucasian comrades. Nevertheless, they received less pay than their European or Asian comrades-in-arms.[153] Corporal punishment (flogging) was also still a disciplinary punishment exclusively for black soldiers. In northern Nigeria, it is not necessarily possible to speak of "voluntary" recruits, as the local tribal chiefs were prescribed contingents of "volunteers" as part of the Indirect Rule. The absolutist rulers did not necessarily take into account the voluntary nature of the troops when providing them for service at the front. During the war, none of the commanding officers of the Nigerian Corps came from Nigeria. (The first Nigerian officers received their licences at the end of the war).

The Nigerian soldiers can hardly have been unaware of the contradiction between their reality and the propagated British interpretation of wanting to protect Africa from German and Italian colonisation.[153] In addition, the Nigerian troops had been fighting alongside their Indian comrades for several years and there was already a strong and media-effective independence movement against British colonial rule in their homeland under Mahatma Gandhi. (India became independent just 22 months after the Second World War.) The exchange of ideas with the Indians striving for independence almost certainly contributed to the fact that Nigerian soldiers returned home from Burma in January 1946[154] with completely new ideas about an independent Nigeria, but with less patience.

In his victory speech, the commander of the troops in Burma, Sir William Slim, did not mention the Nigerian "brothers in arms" at all.[155]

Following World War II, in response to the growth of Nigerian nationalism and demands for independence, successive constitutions legislated by the British government moved Nigeria toward self-government on a representative and increasingly federal basis. On 1 October 1954, the colony became the autonomous Federation of Nigeria. By the middle of the 20th century, the great wave for independence was sweeping across Africa. On 27 October 1958, Britain agreed that Nigeria would become an independent state on 1 October 1960.[156]

In 1957, general elections took place in Nigeria. Political parties, however, tended to reflect the makeup of the three main ethnic groups. The Northern People's Congress (NPC) represented conservative, Muslim, largely Hausa and Fulani interests that dominated the northern region of the country, consisting of three-quarters of the land area and more than half the population of Nigeria. Thus the North dominated the federation government from the beginning of independence. In the 1959 elections held in preparation for independence, the NPC captured 134 seats in the 312-seat parliament.[157] Capturing 89 seats in the federal parliament was the second-largest party in the newly independent country the National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC). The NCNC represented the interests of the Igbo- and Christian-dominated people of the Eastern Region of Nigeria.[157] and the Action Group (AG) was a left-leaning party that represented the interests of the Yoruba people in the West. In the 1959 elections, the AG obtained 73 seats.[157]

The first post-independence national government was formed by a conservative alliance of the NCNC and the NPC. Upon independence, it was widely expected that Ahmadu Bello the Sardauna of Sokoto, the undisputed strong man in Nigeria[158] who controlled the North, would become Prime Minister of the new Federation Government. However, Bello chose to remain as premier of the North and as party boss of the NPC, selected Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, a Hausa, to become Nigeria's first Prime Minister.

On August 30th 1957, a central Nigerian government under Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was formed.

Independence, First Republic

Independent with a British Queen

The Federation of Nigeria was granted full independence on 1 October 1960 under a constitution that provided for a parliamentary government and a substantial measure of self-government for the country's three regions. As First Speaker of the House, Jaja Wachuku received Nigeria's Instrument of Independence, also known as Freedom Charter, on 1 October 1960, from Princess Alexandra of Kent, the Queen's representative at the Nigerian independence ceremonies. Queen Elizabeth II was monarch of Nigeria and head of state, and Nigeria was a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations. The Federal government was given exclusive powers in defence, foreign relations, and commercial and fiscal policy. The monarch of Nigeria was still head of state but legislative power was vested in a bicameral parliament, executive power in a prime minister and cabinet, and judicial authority in a Federal Supreme Court.

1960 the Yoruba-dominated AG became the opposition under its charismatic leader Chief Obafemi Awolowo. However, in 1962, a faction arose within the AG under the leadership of Ladoke Akintola who had been selected as premier of the West.[157] The party leadership under Awolowo disagreed and replaced Akintola as premier of the West with one of their own supporters. However, when the Western Region parliament met to approve this change, Akintola supporters in the parliament started a riot in the chambers of the parliament.[159] In subsequent attempts to reconvene the Western parliament, similar disturbances broke out.[159] Unrest continued in the West and contributed to the Western Region's reputation for, violence, anarchy and rigged elections.[160] Federal Government Prime Minister Balewa declared martial law in the Western Region. Akintola was appointed to head a coalition government in the Western Region. Thus, the AG was reduced to an opposition role in their own stronghold.[159]

First Republic

In October 1963, Nigeria proclaimed itself the Federal Republic of Nigeria, and former Governor-General Nnamdi Azikiwe became the country's first President. The AG was manoeuvred out of control of the Western Region by the Federal Government and a new pro-government Yoruba party, the Nigerian National Democratic Party (NNDP), took over. The 1965 national election produced a major realignment of politics and a disputed result that set the country on the path to civil war.[161] The dominant northern NPC went into a conservative alliance with the new Yoruba NNDP, leaving the Igbo NCNC to coalesce with the remnants of the AG in a progressive alliance. In the vote, widespread electoral fraud was alleged and riots erupted in the Yoruba West where heartlands of the AG discovered they had apparently elected pro-government NNDP representatives.

Dictatorship and War

The January Coup, dictatorship Aguiyi-Ironsi

On 15 January 1966, a group of army officers (the Young Majors) mostly south-eastern Igbos, overthrew the NPC-NNDP government and assassinated the prime minister and the premiers of the northern and western regions. However, the bloody nature of the Young Majors coup caused another coup to be carried out by General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi. The Young Majors went into hiding. Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna fled to Kwame Nkrumah's Ghana where he was welcomed as a hero.[162] Some of the Young Majors were arrested and detained by the Ironsi government. Among the Igbo people of the Eastern Region, these detainees were heroes.[163] In the Northern Region, however, the Hausa-Fulani people demanded that the detainees be placed on trial for murder.[163]

The federal military government that assumed power under General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi was unable to quiet ethnic tensions on the issue or other issues. Additionally, the Ironsi government was unable to produce a constitution acceptable to all sections of the country. Most fateful for the Ironsi government was the decision to issue Decree No. 34 which sought to unify the nation.[164] Decree No. 34 sought to do away with the whole federal structure under which the Nigerian government had been organised since independence. Rioting broke out in the North.[165]

Dictatorship Gowon

The Ironsi government's efforts to abolish the federal structure and the renaming the country the Republic of Nigeria on 24 May 1966 raised tensions and led to another coup by largely northern officers in July 1966, which established the leadership of Major General Yakubu Gowon.[166] The name Federal Republic of Nigeria was restored on 31 August 1966. However, the subsequent massacre of thousands of Igbo in the north prompted hundreds of thousands of them to return to the south-east where increasingly strong Igbo secessionist sentiment emerged. In a move towards greater autonomy to minority ethnic groups, the military divided the four regions into 12 states. However, the Igbo rejected attempts at constitutional revisions and insisted on full autonomy for the east.

The Central Intelligence Agency commented in October 1966 in a CIA Intelligence Memorandum that:[167]

"Africa's most populous country (population estimated at 48 million) is in the throes of a highly complex internal crisis rooted in its artificial origin as a British dependency containing over 250 diverse and often antagonistic tribal groups. The present crisis started" with Nigerian independence in 1960, but the federated parliament hid "serious internal strains. It has been in an acute stage since last January when a military coup d'état destroyed the constitutional regime bequeathed by the British and upset the underlying tribal and regional power relationships. At stake now are the most fundamental questions which can be raised about a country, beginning with whether it will survive as a single viable entity.

The situation is uncertain, with Nigeria, ..is sliding downhill faster and faster, with less and less chance unity and stability. Unless present army leaders and contending tribal elements soon reach agreement on a new basis for the association and take some effective measures to halt a seriously deteriorating security situation, there will be increasing internal turmoil, possibly including civil war.

Biafra War

On 29 May 1967, Lt. Col. Emeka Ojukwu, the military governor of the eastern region who emerged as the leader of increasing Igbo secessionist sentiment, declared the independence of the eastern region as the Republic of Biafra on 30 May 1967.[168] The ensuing Nigerian Civil War resulted in an estimated 3.5 million deaths (mostly from starving children) before the war ended with Gowon's famous "No victor, no vanquished" speech in 1970.[169]

After the war

Following the civil war, the country turned to the task of economic development. The U.S. intelligence community concluded in November 1970 that "...The Nigerian Civil War ended with relatively little rancour. The Igbos were accepted as fellow citizens in many parts of Nigeria, but not in some areas of former Biafra where they were once dominant. Iboland is an overpopulated, economically depressed area where massive unemployment is likely to continue for many years.[170]

The U.S. analysts said that "...Nigeria is still very much a tribal society..." where local and tribal alliances count more than "national attachment. General Yakubu Gowon, head of the Federal Military Government (FMG) is the accepted national leader and his popularity has grown since the end of the war. The FMG is neither very efficient nor dynamic, but the recent announcement that it intends to retain power for six more years has generated little opposition so far. The Nigerian Army, vastly expanded during the war, is both the main support to the FMG and the chief threat to it. The troops are poorly trained and disciplined and some of the officers are turning to conspiracies and plotting. We think Gowon will have great difficulty in staying in office through the period which he said is necessary before the turnover of power to civilians. His sudden removal would dim the prospects for Nigerian stability."

"Nigeria's economy came through the war in better shape than expected." Problems exist with inflation, internal debt, and a huge military budget, competing with popular demands for government services. "The petroleum industry is expanding faster than expected and oil revenues will help defray military and social service expenditures... "Nigeria emerged from the war with a heightened sense of national pride mixed with an anti-foreign sentiment, and an intention to play a larger role in African and world affairs." British cultural influence is strong but its political influence is declining. The Soviet Union benefits from Nigerian appreciation of its help during the war, but is not trying for control. Nigerian relations with the US, cool during the war, are improving, but France may be seen as the future patron. "Nigeria is likely to take a more active role in funding liberation movements in southern Africa." Lagos, however, is not perceived as the "spiritual and bureaucratic capital of Africa"; Addis Ababa has that role...."

Foreign exchange earnings and government revenues increased spectacularly with the oil price rises of 1973–74. On July 29, 1975, Gen. Murtala Mohammed and a group of officers staged a bloodless coup, accusing Gen. Yakubu Gowon of corruption and delaying the promised return to civilian rule. General Mohammed replaced thousands of civil servants and announced a timetable for the resumption of civilian rule by 1 October 1979. He was assassinated on 13 February 1976 in an abortive coup and his chief of staff Lt. Gen. Olusegun Obasanjo became head of state.

Second Republic

A constituent assembly was elected in 1977 to draft a new constitution, which was published on 21 September 1978, when the ban on political activity was lifted. In 1979, five political parties competed in a series of elections in which Alhaji Shehu Shagari of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) was elected president.[171] All five parties won representation in the National Assembly.

During the 1950s prior to independence, oil was discovered off the coast of Nigeria. Almost immediately, the revenues from oil began to make Nigeria a wealthy nation. However, the spike in oil prices from $3 per barrel to $12 per barrel, following the Yom Kippur War in 1973 brought a sudden rush of money to Nigeria.[172] Another sudden rise in the price of oil in 1979 to $19 per barrel occurred as a result of the lead-up to the Iran–Iraq War.[172] All of this meant that by 1979, Nigeria was the sixth largest producer of oil in the world with revenues from oil of $24 billion per year.[171]

In 1982, the ruling National Party of Nigeria, a conservative alliance led by Shehu Shagari, had hoped to retain power through patronage and control over the Federal Election Commission. In August 1983, Shagari and the NPN were returned to power in a landslide with a majority of seats in the National Assembly and control of 12 state governments. But the elections were marred by violence and allegations of widespread voter fraud including missing returns, polling places failing to open, and obvious rigging of results. There was a fierce legal battle over the results, with the legitimacy of the victory at stake.[173][174]