| Markham's storm petrel | |

|---|---|

.jpeg.webp) | |

| Bird off Peru | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Hydrobatidae |

| Genus: | Hydrobates |

| Species: | H. markhami |

| Binomial name | |

| Hydrobates markhami (Salvin, 1883) | |

| |

| Distribution: blue = non-breeding | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

|

List

| |

Markham's storm petrel (Hydrobates markhami) is a species of storm petrel in the family Hydrobatidae. An all-black to sooty brown seabird, Markham's storm petrel is difficult to differentiate from the black storm-petrel (Hydrobates melania) in life, and was once described as conspecific with, or biologically identical to, Tristram's storm petrel (Hydrobates tristrami). Markham's storm petrel inhabits open seas in the Pacific Ocean around Peru, Chile, and Ecuador, but only nests in northern Chile and Peru, with ninety-five percent of all known breeding populations in 2019 found in the Atacama Desert. First described by British ornithologist Osbert Salvin in 1883, the bird was named in honor of Albert Hastings Markham, a naval officer who collected the type specimen off Peru.

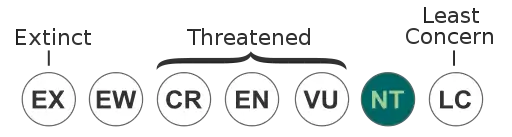

Markham's storm petrel nests in natural cavities in saltpeter, and pairs produce one egg per season. After hatching, fledglings make their way to sea, and can be either attracted to or disoriented by artificial lights. The diet of Markham's storm petrel consists of fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans, with about ten percent of stomach contents traceable to scavenging. Since at least 2012, Markham's storm petrel has been listed as an endangered species in Chile, and, in 2019, Markham's storm petrel was classified as Near Threatened due to habitat loss on its nesting grounds. Conservation efforts have been undertaken in Chile.

Taxonomy

Ornithologist Osbert Salvin first described Markham's storm petrel as Cymochorea markhami in 1883.[2][3] The species is named after Albert Hastings Markham, a British explorer and naval officer who collected the type specimen off Peru.[4] The bird was thought by ornithologist James L. Peters in 1931 as conspecific, or biologically identical, with Tristram's storm petrel (Oceanodroma tristrami), though the two species were later distinguished by the size of their tarsus (the "lower leg" of a bird).[2][5] Similarly, ornithologist Reginald Wagstaffe considered Tristram's storm petrel a subspecies of Markham's storm petrel in 1972, though subsequent research recognized them as different species.[6]

In molecular phylogenetic studies published in 2004 and 2017 the genus Oceanodroma was found to be paraphyletic (not a natural group) with respect to Hydrobates, with the European storm petrel (Hydrobates pelagicus) embedded within the larger Oceanodroma.[7][8] The genus Hydrobates was introduced by Friedrich Boie in 1822 and thus has priority over Oceanodroma which was introduced by Ludwig Reichenbach in 1853. Therefore, to create monophyletic (natural) genera, all the species in Oceanodroma were transferred to Hydrobates, including Markham's storm petrel.[9][10]

The following cladogram shows the results of the phylogenetic analysis by Wallace and colleagues, 2017.[8]

| Hydrobates |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The northern storm petrel family, Hydrobatidae, is a group of seabirds characterized by long legs and a high adaption to marine environments, with its eighteen[11] species being predominately endemic to the northern hemisphere. Within the Hydrobatidae, Markham's storm petrel is a member of the genus Hydrobates, the only genus in the family, and is large compared to other members.[4][12] Hydrobatidae probably diverged from other petrels at an early stage; according to ornithologist John Warham, the petrel group had "substantial radiation" by the Miocene.[13] Storm petrel fossils are rare, but have been found in Upper Miocene deposits in California.[14]

Description

Markham's storm petrel is a large and slender storm petrel. As in other species of its genus, the wings are slender with tapering tips and a distinct bend at the carpus (wrist), while the tail is deeply forked. The fresh plumage is all-black to sooty brown with a dull lead-gray gloss on its head, neck and mantle. With wear, the plumage becomes browner overall. A distinct crescent-shaped, grayish bar runs diagonally over the upper side of the inner wing. The iris is brown and the bill and feet are black. The bill is shorter than in most related species, whereas the nasal tube on top of the bill is long, reaching to the mid-length of the beak.[4][15][16] Adult males have an average wingspan of 172.7 mm (6.80 in) compared to a wingspan of 169.8 mm (6.69 in) in adult females, and the tarsus is 23.9 mm (0.94 in) in adult males and 24.2 mm (0.95 in) in females. Tails are 92.7 mm (3.65 in) in adult males and 89.4 mm (3.52 in) in adult females. Sexes are alike, without any morphological differences.[2][4]

Similar birds within its range include the black storm petrel (Hydrobates melania) and the dark variety of Leach's storm petrel (Hydrobates leucorhous). From the black storm petrel, it differs in having a much shorter tarsus, and in that the gray bar on the upper side of the wing is more distinct and reaches closer to the carpus. Markham's storm petrel also differs in its shorter neck and more angular head, and in the more pronounced forking of the tail. From Leach's storm petrel, it differs in its more pronounced tail forking and its longer wings and larger size. Differences in flight patterns also aid in separating these species. Markham's storm petrel typically flies leisurely and often glides with intermittent shallow and rapid wingbeats, whereas the black storm-petrel rarely glides and tends to use deep wingbeats. Markham's storm petrel also typically flies greater than 1 m (3.3 ft) over the ocean surface, in contrast to the black storm-petrel. Leach's storm petrel generally uses deeper wingbeats and its flight is more bouncing.[4][17][18]

The calls of Markham's storm petrel have been described as series of "purrs", "wheezes", and "chatters".[4]

Distribution and habitat

Markham's storm petrel inhabits waters in the Pacific Ocean around Ecuador, Peru, and Chile,[4][19] though sightings have occurred on the equator west of the Galápagos Islands,[20] within the Panama Bight,[21] and off Baja California.[22] Sightings off Baja California might mistake Markham's storm petrel for the black storm petrel due to difficulties of distinguishability in the field.[20] Spear and Ainley observed Markham's storm petrel from 29°54′S 118°01′W / 29.90°S 118.02°W to 16°33′N 118°01′W / 16.55°N 118.02°W, which expanded its westward range from a compilation of sightings recorded by ornithologist Richard S. Crossin in 1974.[17] Its presence is highly unlikely in the Atlantic Ocean outside of freak vagrancies,[23] and in 2007, Spear and Ainley classified the species as endemic to the Humboldt Current.[17] Despite its range, Markham's storm petrel only nests in Peru and Chile.[1]

A survey conducted by Spear and Ainley from 18°N to 30°S, west to 115°, found greatest densities of the bird during austral autumn (the non-breeding season) offshore between Guayaquil and Lima. During spring, the breeding population splits into two around southern Peru and northern Chile, stretching out 1,700 km (1,100 mi) offshore.[17] Nesting colonies were first reported in the late 1980s to early 1990s.[14][24] In 1992, 1,144 nests, equal to a population of approximately 2,300 nesting pairs, were found 5 km (3.1 mi) inland on Paracas Peninsula in Peru.[24][25] Two separate discoveries occurred in Chile in 2013: one of nesting sites south of the Acha valley in Arica Province and one of a recording of a bird singing. After further exploration in November 2013 based on the recording,[19][26] in 2019, populations of 34,684 nests in Arica, 20,000 nests in Salar Grande, and 624 nests in Pampa de la Perdiz were found in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. This translated to about ninety-five percent of the known breeding population at the time.[27]

Behavior and ecology

Markham's storm petrel nests in burrows, natural cavities, and holes in saltpeter crusts. Nests in saltpeter cavities have been reported in Pampa de Camarones in northern Chile, and inland on Paracas Peninsula.[24][26] In Peru, egg laying occurs from late June to August;[24] in Chile, an analysis of three colonies in the Atacama Desert found a five-month reproductive cycle, from arrival at colonies to departure of fledglings, across all three colonies, though pairs could reproduce asynchronously. This could lead to an overall ten-month reproductive season.[27] Pairs produce one egg per season,[28] and adults in nests were found to vocalize when a recording of Markham's storm petrel vocalizations was played at the entrance to the nest.[27] The eggs are pure white without gloss.[2] The average incubation period in Paracas is 47 days (n = 28). Both the female and male engage in duties related to incubation. The shifts in incubation lasted three days or less in Paracas. There are "[n]o details on the breeding colonies in Chile".[4]

The mean width of the widest part of nest burrow openings in Chile was measured at 10.3 cm (4.1 in) with a standard deviation of ± 3.1 cm (1.2 in), with the narrowest part measured at 6.8 cm (2.7 in) with a deviation of ± 1.9 cm (0.75 in). The average depth of the burrows was greater than 40 cm (16 in).[19] After hatching, in Chile, the fledglings move towards the sea after a chick phase.[29] Fledglings are either attracted to or disoriented by artificial lights, an occurrence common to burrow-nesting petrels.[19][30] Molting adults are seen in the southern spring and early summer, molting juveniles several months earlier.[15]

A 2007 study found that a sample of fifteen Markham's storm petrel had consumed the fish Diogenichthys laternatus and Vinciguerria lucetia, among other foods. Markham's storm petrel was found to have a lower dietary diversity than other small petrels, though dietary diversity was high generally among small petrels compared to other birds analyzed.[31] A 2002 study found its main diet by mass consisted of fish (namely the Peruvian anchovy Engraulis ringens), cephalopods (namely the octopus Japetella sp.), and crustaceans (namely the pelagic squat lobster Pleuroncodes monodon), with about ten percent of analyzed stomach contents suggestive of scavenging. Based on large variations in the types of food it consumes, and its tendency to scavenge, Markham's storm petrel appears to opportunistically forage near the surface of the ocean.[32] The proportion of birds that feed or rest, compared to flying in transit, was significantly higher in austral autumn than spring according to the 2007 study.[17]

A 2018 study found the ectoparasitical stick-tight flea (Hectopsylla psittaci) on two birds out of ten captured in Pampa de Chaca within the Arica y Parinacota Region. Both specimens were found in the lorum (the region between the eyes and nostrils) on each bird. The turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) served as a possible source for the transition between hosts, as the two were observed nesting in the same colony.[33] Researchers Rodrigo Barros et al. described the bird as "one of the least known seabirds in the world".[27]

Threats and conservation

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimated the population of Markham's storm petrel in 2019 as between 150,000 and 180,000 individuals, with between 100,000 and 120,000 mature individuals.[1] The global breeding population has been estimated at 58,038 pairs.[34] The IUCN estimated the population of Markham's storm petrel was in decline generally based on a study which proposed that approximately 21,000 fledglings die each year,[27] though the IUCN noted juvenile seabirds have a higher mortality rate in general based on environmental parameters, age, and sex.[1] The IUCN could not give a specific population trend for mature individuals because as these are unknown.[1] Prior to 2019, no concrete population estimates for Markham's storm petrel existed, with a 2004 estimate placing the population at likely in excess of 30,000 individuals,[35] a 2007 estimate placing the population between 806,500 in austral spring and 1,100,000 in austral autumn,[17] and a 2012 estimate placing the population at 50,000 overall individuals.[36]

Despite its very large population size, in 2019, the IUCN listed the conservation status of Markham's storm petrel as Near Threatened due to habitat loss on its nesting grounds.[1] Since at least 2012, the bird has been classified as endangered in Chile,[19] and, in 2018, the Chilean Ministry of the Environment (MMA) classified the bird as in danger of extinction.[37][38] Conservation efforts have been undertaken in Chile by the Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG), a department of the Ministry of Agriculture. In 2014, the SAG stated it already rescued a large number of juveniles who lost their way likely due to lighting in cities, a phenomenon that had been evident in the Tarapacá Region for at least ten years prior.[39]

In 2018, the SAG reported it returned approximately 2,000 juvenile birds to their natural habitat after the birds fell on streets, the birds apparently believing they had already reached the coast.[29] Officials handed out informational brochures to citizens in 2019 which informed them about the start of the juvenile flight season. The brochures instructed citizens what to do if they found a grounded Markham's storm petrel.[lower-alpha 1][27][38] Similarly, in 2015, Peruvian officials instructed citizens how to transport a fallen Markham's storm petrel if they should find one.[41] In Ecuador, as of 2018, the species is classified as Near Endangered.[42]

Chief threats to Markham's storm petrel in Chile include garbage, roadways across nesting colonies, mining, new construction and development, and artificial lights.[27] In 2013, bulldozer trails, dogs and an encampment of road construction workers were observed near nesting areas close to Arica.[19] Other than habitat loss, salt mines in northern Chile may also provide a source of habitat disturbance through artificial lights; a company reported over a three-month span that 3,300 fledglings had been grounded due to their lights.[40] Fallen birds were reported in Tacna, Peru, in 2015, the birds having possibly fallen due to artificial lights.[41] In 2019, the Chilean MMA produced a plan which included Markham's storm petrel that sought to evaluate proposals such as updating a light pollution standard to mitigate the effects of artificial lights on the birds and designating a nesting site at Pampa de Chaca as a protected area.[43][37]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 BirdLife International (2019). "Hydrobates markhami". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22698543A156377889. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22698543A156377889.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Murphy, Robert Cushman (1936). Oceanic Birds of South America: A Study of Species of the Related Coasts and Seas, Including the American Quadrant of Antarctica, Based upon the Brewster-Sanford Collection in the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 2. The Macmillan Company. pp. 739–741.

- ↑ Salvin, Osbert (1883). "List of the birds collected by Captain A. H. Markham on the west coast of America". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1883 (Part 3): 419–432 [430].

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Drucker, J.; Jaramillo, A. (2020). Schulenberg, Thomas S (ed.). "Markham's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma markhami". Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bow.maspet.01. S2CID 216420851.

- ↑ Peters, James L., ed. (1931). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Christidis, Lee; Boles, Walter E., eds. (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. CSIRO Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9780643065116.

- ↑ Penhallurick, John; Wink, Michael (2004). "Analysis of the taxonomy and nomenclature of the Procellariiformes based on complete nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 104 (2): 125–147. Bibcode:2004EmuAO.104..125P. doi:10.1071/MU01060. S2CID 83202756.

- 1 2 Wallace, S.J.; Morris-Pocock, J.A.; González Solís, J.; Quillfeldt, P.; Friesen, V.L. (2017). "A phylogenetic test of sympatric speciation in the Hydrobatinae (Aves: Procellariiformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 107: 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.09.025. PMID 27693526.

- ↑ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2023). "Petrels, albatrosses". IOC World Bird List Version 13.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ↑ Chesser, R.T.; Burns, K.J.; Cicero, C.; Dunn, J.L.; Kratter, A.W; Lovette, I.J.; Rasmussen, P.C.; Remsen, J.V. Jr; Stotz, D.F.; Winker, K. (2019). "Sixtieth supplement to the American Ornithological Society's Check-list of North American Birds". The Auk. 136 (3): 1–23. doi:10.1093/auk/ukz042.

- ↑ Winkler, David W.; Billerman, Shawn M.; Lovette, Irby J. (2020). "Hydrobatidae: Northern Storm-Petrels". Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bow.hydrob1.01. S2CID 216364538.

- ↑ "Hydrobatinae". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ Warham, John (1996). "Evolution and Radiation". The Behaviour, Population Biology and Physiology of the Petrels. Elsevier Ltd. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-12-735415-6.

- 1 2 Carboneras, C. (1992). "Family Hydrobatidae (Storm-petrels)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 258–271 [258–259]. ISBN 84-87334-10-5.

- 1 2 Onley, Derek J.; Scofield, Paul (2007). Albatrosses, Petrels and Shearwaters of the World. Helm Field Guides. Christopher Helm. p. 232–233. ISBN 9780713643329.

- ↑ Howell, Steve N. G. (2012). Petrels, albatrosses, and storm-petrels of North America: a photographic guide. Princeton (N.J.): Princeton university press. pp. 427–430. ISBN 978-0-691-14211-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Spear, Larry B.; Ainley, David G. (2007). "Storm-Petrels of the Eastern Pacific Ocean: Species Assembly and Diversity along Marine Habitat Gradients". Ornithological Monographs. American Ornithological Society (62): 8, 13, 27, 37–40. doi:10.2307/40166847. JSTOR 40166847.

- ↑ Brown, RGB (1980). "The Field Identification of Black and Markham's storm-petrels Oceanodroma melania and O. markhami" (PDF). American Birds. 34: 868. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 31, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Torres-Mura, Juan C.; Lemus, Marina L. (2013). "Breeding of Markham's Storm-Petrel (Oceanodroma markhami, Aves: Hydrobatidae) in the Desert of Northern Chile" (PDF). Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. Sociedad de Biología de Chile. 86 (4): 497–499. doi:10.4067/S0716-078X2013000400013. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2018.

- 1 2 Crossin, Richard S. (1974). "The Storm Petrels (Hydrobatidae)". In King, Warren B. (ed.). Pelagic Studies of Seabirds in the Central and Eastern Pacific Ocean. p. 187. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.158. hdl:10088/5305.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ↑ Spear, Larry B.; Ainley, David G. (1999). "Seabirds of the Panama Bight". Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. 22 (2): 197. JSTOR 1522207.

- ↑ Pyle, Peter (1993). "A Markham's Storm-Petrel in the Northeastern Pacific" (PDF). Western Birds. 24: 108–110. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 3, 2019.

- ↑ Flood, Robert L. (2009). "'All-dark' Oceanodroma Storm-Petrels in the Atlantic and Neighbouring Seas" (PDF). British Birds. 102: 365. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 1, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Jahnckea, Jamie (1993). "Primer informe del área de anidación de la golondrina de tempestad negra Oceanodroma markhami (Salvin, 1883)" [First Report of the Nesting Area of the Golondrina de Tempestad Negra Oceanodroma markhami (Salvin, 1883)]. In Castillo de Mar uenda E (ed.). Memorias X Congreso Nacional de Biología (in Spanish). pp. 339–343.

- ↑ Jahnckea, Jamie (1994). "Biología y conservación de la golondrina de tempestad negra Oceanodroma markhami (Salvin 1883) en la península de Paracas, Perú" [Biology and Conservation of the Golondrina de Tempestad Negra Oceanodroma markhami (Salvin 1883) in the Paracas Peninsula, Peru]. Informe Técnico (in Spanish). APECO.

- 1 2 Schmitt, F.; Rodrigo, B.; Norambuena, H. (2015). "Markham's storm petrel breeding colonies discovered in Chile" (PDF). Neotropical Birding. 17: 5–10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Barros, Rodrigo; Medrano, Fernando; Norambuena, Heraldo V.; Peredo, Ronny; Silva, Rodrigo; de Groote, Felipe; Fabrice, Schmitt (2019). "Breeding Phenology, Distribution and Conservation Status of Markham's Storm-Petrel Oceanodroma markhami in the Atacama Desert". Ardea. 107 (1): 75, 77–79, 81. doi:10.5253/arde.v107i1.a1. S2CID 164959486.

- ↑ Torres, Amalia. "Más de 700 golondrinas de mar han sido rescatadas por los vecinos de Arica en el último mes" [More than 700 Golondrinas de Mar have been Rescued by the Residents of Arica in the Last Month]. El Mercurio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 31, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- 1 2 Yáñez, Cecilia (April 21, 2019). "La triste historia de la golondrina de mar que se está perdiendo en la ciudad" [The Sad History of the Golondrina de Mar that is Getting Lost in the City]. La Tercera (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 2, 2020.

- ↑ Rodríguez, Airam; Holmes, Nick D.; Ryan, Peter G.; Wilson, Kerry-Jayne; Faulquier, Lucie; et al. (February 2017). "Seabird Mortality Induced by Land-based Artificial Lights". Conservation Biology. Society for Conservation Biology. 31 (5): 989. doi:10.1111/cobi.12900. hdl:10400.3/4515. PMID 28151557.

- ↑ Spear, Larry; Ainley, David; Walker, William (2007). "Foraging Dynamics of Seabirds in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean" (PDF). Studies in Avian Biology. Cooper Ornithological Society. 35: 1, 43, 73. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 8, 2020.

- ↑ García-Godos, Ignacio; Goya, Elisa; Jahncke, Jamie (2002). "The Diet of Markham's Storm Petrel Oceanodroma markhami on the Central Coast of Peru" (PDF). Marine Ornithology. 30 (2): 77, 79, 81–82. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 26, 2018.

- ↑ Cerpa, Patrich; Medrano, Fernando; Peredo, Ronny (2018). "Jumps from Desert to the Sea: Presence of the Stick–tight Flea Hectopsylla psittaci in Markham's Storm–Petrel (Oceanodroma markhami) in the North of Chile". Revista Chilena de Ornitología (in Spanish). Unión de Ornitólogos de Chile. 24 (1): 40–42.

- ↑ Medrano, Fernando; Silva, Rodrigo; Barros, Rodrigo; Terán, Daniel; Peredo, Ronny; et al. (2019). "Nuevos antecedentes sobre la historia natural y conservación de la golondrina de mar negra (ocenodroma markhami) y la golondrina de mar de collar (ocenodroma hornbyi) en Chile" [New Information on the Natural History and Conservation of Markham's Storm-petrel (Oceanodroma markhami) and Hornby's Storm-petrel (Oceanodroma hornbyi) in Chile] (PDF). Revista Chilena de Ornitología (in Spanish). Unión de Ornitólogos de Chile. 25 (1): 26. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 6, 2020.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2018). "Hydrobates markhami". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Hydrobates markhami". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- 1 2 "Resolución exenta n° 1113: Da inicio al proceso de el aboración del plan de recuperación, conservación y gestión de las golondrinas del mar del norte de chile" [Exempt Resolution n° 1113: Initiates the Process of Drawing Up the Plan for the Recovery, Conservation and Management of the Golondrinas Del Mar of Northern Chile] (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio del Medio Ambiente. September 11, 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2020.

- 1 2 "SAG inició campaña de difusión para rescate de golondrinas de mar negra" [SAG Started a Dissemination Campaign to Rescue Golondrinas de Mar Negra]. El Longino (in Spanish). March 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020.

- ↑ "SAG inicia rescate de golondrinas de mar negra" [SAG Begins Rescue of Golondrinas de Mar Negra] (in Spanish). Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero. April 14, 2014. Archived from the original on June 1, 2020.

- 1 2 Gilman, Sarah (July 20, 2018). "South America's Otherworldly Seabird". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020.

- 1 2 "Tacna: reportan presencia inusual de golondrinas oceánicas" [Tacna: Unusual Presence of Oceanic Swallows Reported]. El Comercio (in Spanish). November 21, 2015. Archived from the original on September 10, 2020.

- ↑ Jiménez-Uzcátegu, G.; Freile, G. F.; Santander, T.; Carrasco, L.; Cisneros-Heredia, D. F.; et al. (2018). "Listas Rojas de Especies Amenazadas en el Ecuador" [Red Lists of Threatened Species in Ecuador] (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio del Ambiente. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 31, 2019.

- ↑ Levi, Paula Diaz (January 22, 2020). "Continúa el ocaso de las golondrinas de mar: piden reducir contaminación lumínica y proteger sitios de nidificación" [The Decline of Golondrinas de Mar: They Ask to Reduce Light Pollution and Protect Nesting Sites]. Ladera Sur (in Spanish). Archived from the original on June 1, 2020.

External links

- Vocalizations of Markham's storm petrel from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology's Macaulay Library

- Video of Markham's storm petrel from Macaulay Library