Liberty Party | |

|---|---|

| Leader(s) | James G. Birney Gerrit Smith |

| Founded | 1840 |

| Dissolved | 1860 |

| Split from | American Anti-Slavery Society |

| Merged into | Free Soil Party Republican Party |

| Headquarters | Warsaw, New York |

| Newspaper | The Emancipator The Philanthropist |

| Ideology | Abolitionism |

| Political position | Big tent |

The Liberty Party was an abolitionist political party in the United States prior to the American Civil War. The party experienced its greatest activity during the 1840s, while remnants persisted as late as 1860. It supported James G. Birney in the presidential elections of 1840 and 1844. Other prominent figures connected with the Liberty Party included Gerrit Smith, Salmon P. Chase, Joshua Leavitt, Henry Highland Garnet, and John Greenleaf Whittier. The attempted to work within the federal system created by the United States Constitution to diminish the political influence of the Slave Power and advance the cause of universal emancipation and an integrated, egalitarian society.

In the late 1830s, the antislavery movement in the United States was divided between Garrisonian abolitionists, who advocated nonresistance and anti-clericalism and opposed any involvement in electoral politics, and Anti-Garrisonians, who increasingly argued for the necessity of direct political action and the formation of an anti-slavery third party. At a meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in May 1840, the Anti-Garrisonians broke away from the Old Organization to form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. The New Organization included many political abolitionists who gathered in upstate New York to organize the Liberty Party ahead of the 1840 elections. They rejected the Garrisonian singular emphasis on moral suasion and asserted that abolitionists should oppose slavery by all available means, including by coordinating at the ballot box.[1]

The party attracted support from former Whigs and Jacksonian Democrats alienated by their parties' proslavery national leaderships, as well as the early involvement of women and African Americans.[2] Internal disagreements over whether and how the party should cooperate with abolitionists who remained within the two major parties and to what extent Liberty candidates should address issues beyond slavery intensified after 1844.[3] In 1847 party leaders favoring a coalition with antislavery Conscience Whigs and Barnburner Democrats succeeded in nominating John P. Hale for president over Gerrit Smith, the candidate of the radical Liberty League. Hale was an Independent Democrat who had opposed the gag rule in Congress and voted against the annexation of Texas but stopped short of endorsing immediate emancipation.[4] Following the 1848 convention of antislavery politicians at Buffalo, New York, Hale withdrew from the race in favor of Martin Van Buren, and most of the Liberty Party folded into the larger Free Soil Party.[5] Smith and the Liberty League continued to maintain an separate organization and supported an independent ticket in each ensuing election until 1860.[6] Many former Liberty leaders subsequently became founders of the Republican Party, including Salmon Chase.

History

Creation, 1839–41

Efforts by abolitionists to organize politically began in the late 1830s. The earliest attempts were not made with a new party in mind, as abolitionists hoped to influence the two existing parties. Antislavery voters in New England demanded candidates announce their position on slavery and awarded or withheld their support accordingly. The success of the "questioning system" proved fleeting, however, as abolitionists discovered candidates frequently would issue antislavery pledges during a campaign, only to abandon their commitments once elected. In the highly partisan environment of the Second Party System, the need for a dedicated antislavery party to effectively oppose the bipartisan proslavery consensus gradually gained recognition.[7] After 1837, the Democratic Party leadership sought actively to expel antislavery Jacksonians such as Thomas Morris and John P. Hale whose principled opposition to slavery was seen as a threat to party unity.[8] While the Whig Party sometimes sought to ingratiate itself with abolitionists, the influence of southern nullifiers and proslavery northern Cotton Whigs prevented the party from taking a strong antislavery stance. Committed to the union of the states, both parties sought to suppress issues such as slavery which threatened to split the country along sectional lines.[9] Their strong opposition to abolitionism and intolerance of antislavery politicians within their own ranks led many abolitionists to conclude that only by working outside the existing parties could abolitionists effectively oppose slavery at the ballot box.

The first movement toward independent antislavery politics began in the fall of 1839 with abolitionist meetings and editorials urging the creation of a new party based on solid antislavery principles. The party was established on April 1, 1840, at Albany, New York by a gathering of 121 delegates from six states who nominated Birney for president and Thomas Earle for vice president. The initial response to the Albany convention was lukewarm; while the Garrisonians continued to oppose any involvement in electoral politics, others felt the nominations were premature and that the political abolitionists needed more time to persuade their colleagues of the necessity of independent political action for the new party to be successful.[10] Nevertheless, electoral tickets pledged to Birney and Earle were organized in every free state. Concerns that the party was still too young to attract the support of most abolitionists proved warranted. Birney polled fewer than 7,000 votes in the 13 states where there were electors pledged to him; in four of these (Connecticut, Indiana, New Jersey, and Rhode Island) he received fewer than 100 votes. He received no votes from the slave states, where the party had not been organized. The Whig ticket of William Henry Harrison and John Tyler was elected with 234 electoral votes to 60 for the incumbent Democrat Martin Van Buren; Harrison's share of the vote in the free states (52.42%) dwarfed Birney's less than one percent showing.[11]

The party initially went by a number of different names, including the Human Rights Party, the Abolition Party, and the Freemen's Party. The 1841 national convention held at Albany selected the "Liberty Party" as the movement's official name.[12]

Rise, 1841–43

The Liberty Party experienced rapid growth in the years following the 1840 United States elections, particularly in New England and areas of Yankee settlement. Events in Washington helped drive support for antislavery politics. In April 1841, Harrison died and was succeeded by Vice President John Tyler, who became the 10th president of the United States. A Virginian and a slaveholder, Tyler was one of the southern conservatives who joined the Whig Party after 1834 to oppose the expansion of executive power under Andrew Jackson. Tyler broke with Whig congressional leaders over the proposal to recharter the Bank of the United States, leading to his exit from the Whig Party before the end of 1841; significantly for abolitionists, he was an early and ardent advocate of the annexation of Texas. Tyler believed American acquisition of Texas was necessary to secure the future of slavery in the United States; he, along with Secretary of State John C. Calhoun, feared that if Texas became aligned with the British Empire, it would become a haven for freedom seekers and weaken slavery in the Lower South. Abolitionists drew similar conclusions and opposed Texas annexation as a measure likely to increase the political might of the Slave Power. The Tyler-Texas Treaty drew opposition from moderate antislavery congressmen as well, including Hale and Benjamin Tappan. As northern opposition to annexation mounted, the indecision of the Whigs and Democrats increased the attractiveness of the Liberty Party to antislavery voters as the only principled anti-annexation party.[13][14]

Between 1841 and 1843, abolitionist opinion shifted perceptibly in favor of independent political action, and the Liberty Party was the recipient of this outpouring of support. While William Lloyd Garrison remained a prominent and influential figure, the failure of moral suasion discredited the approach of the AASS, and by 1844, "the Liberty Party was the major vehicle for serious abolitionist sentiment in every state."[15] This support translated to scattered successes in local and state legislative races in areas where abolitionists were an organized and active majority of voters. Elsewhere, Liberty voters could play kingmaker in areas where neither opposing party controlled a majority of the electorate. In the highly competitive and closely divided environment of the Second Party System, even a modest showing for the Liberty candidates could have deep and lasting effects. Six Liberty members were elected to the Massachusetts General Court in 1842, where they held the balance of power in the divided legislature. That year, Samuel Sewall polled 5.4 percent as the Liberty candidate for governor, enough to hold both leading candidates below a majority and send the election to the Massachusetts Senate. The strategy of the Liberty members to leverage their votes to produce a deadlock narrowly failed when one Whig member voted with the Democrats to ensure the abolitionists' defeat, and John Greenleaf Whittier wrote that Sewall "came within a hair's breadth of being governor."[16]

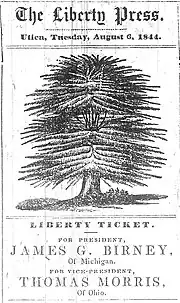

The 1842 campaign in Massachusetts raised significant questions in the internal debate over party strategy. Most Liberty members conceived of the party as a moral crusade to purify American politics from the corrupting influence of the Slave Power. They had renounced their past party allegiances in the belief that the established parties were institutionally committed to slavery and therefore incapable of being converted to abolitionist principles. Many disavowed any cooperation with the established parties, even when local candidates had proven antislavery records. While Independent Democrats like Hale and Conscience Whigs like John Quincy Adams and Joshua Reed Giddings might share some abolitionist priorities, they would still campaign for their parties' proslavery national candidates and did not support immediate, universal emancipation. Editors like Joshua Leavitt of The Emancipator and James Caleb Jackson of the Utica Liberty Press argued that helping to elect such "major party" opponents of slavery ultimately strengthened the Slave Power by extending the life of the established proslavery parties; they called for the Liberty Party to remain an independent organization and work to defeat the proslavery parties outright. Another faction, based in Ohio, sought a coalition with antislavery Whigs and Democrats. Led by Salmon P. Chase and Gamaliel Bailey, they aimed to broaden the party's appeal beyond the abolitionist movement by emphasizing opposition to slavery's extension and the negative effects of slavery for white northerners.[17]

Strategic disagreements between Leavitt and Chase threatened to divide the party in the approach to the 1844 presidential election. The 1841 national convention had nominated Birney for president and Thomas Morris for vice president. Chase hoped to recruit a nationally prominent politician such as Adams, New York Governor William Seward, or Judge William Jay to head the Liberty ticket, and wrote to Birney suggesting that he withdraw from the race. The suggestion offended Birney and enraged Leavitt. Henry B. Stanton, who supported Birney, reported that many in the Massachusetts Liberty Party preferred Jay, including Sewall and Whittier. When the Liberty National Convention met at Buffalo, New York in August 1843, however, Birney and Morris were nominated unanimously.[18] The platform adopted by the Buffalo convention showed Chase's influence. Conceding that the United States Congress lacked the authority to abolish slavery directly, it demanded the "absolute and unqualified divorce" of the federal government from slavery: abolition of slavery in the territories, repeal of the gag rule, and voiding the Fugitive Slave Clause and other proslavery provisions of the United States Constitution. In this way, the platform writers hoped to contain and ultimately suffocate slavery. The platform sharply criticized the abridgement of states' rights and civil liberties in cases such as Prigg v. Pennsylvania that upheld the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. It attacked the proslavery bias of the national government and demanded "the example and influence of national authority ought to be arrayed on the side of liberty and free labor."

The Liberty party has not been organized merely for the overthrow of slavery; its first decided effort must, indeed, be directed against slave-holding as the grossest and most revolting manifestation of despotism, but it will also carry out the principle of equal rights into all its practical consequences and applications, and support every just measure conducive to individual and social freedom.[19]

Crisis, 1844–47

Birney received 62,000 votes in the free states, a nearly tenfold increase over his 1840 result. In five states (Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, and Vermont) his share of the total vote exceeded five percent. He received no votes in the slave states.[20] The major issue in the campaign was the annexation of Texas. Martin Van Buren, the early presumptive nominee of the Democratic Party, opposed annexation on the grounds that it would inflame sectional tensions between the free and slave states. This position cost him the support of the southern Democrats, and James K. Polk was nominated for president on a pro-annexation platform.[21] Henry Clay, the candidate of the Whigs, assumed an ambivalent stance on Texas in an effort to hold together his party's fracturing coalition. He initially opposed annexation, then supported it late in the campaign, only to subsequently clarify that he favored annexation only if it could be achieved without war with Mexico.[22] Abolitionists mistrusted Clay because of his status as a slaveholder as well as his previous interactions with the abolitionist movement. In a campaign visit to Richmond, Indiana in 1842, Clay angrily denounced a group of Quakers who called on him to manumit his slaves.[23] He distanced himself from his cousin Cassius Clay, a prominent antislavery editor, and repeatedly attacked the abolitionist movement as divisive and incendiary. A popular abolitionist song, published in 1844, included the lines, "Railroads to emancipation, / Cannot rest on Clay foundation."[24] Polk won the election with 170 electoral votes to 105 for Clay. Polk carried New York and Michigan with less than a majority; if the Liberty voters in these states had all voted for Clay, Clay would have gained both states and thus the presidency. This has led some historians to suggest that the Liberty Party was a spoiler in 1844, diverting votes that would otherwise have gone to Clay.[25] However, a substantial minority of Liberty voters in 1844 (including vice presidential candidate Thomas Morris) were former Democrats and had no love for Clay. Liberty Party leaders such as Chase and Gerrit Smith aligned more closely with the Jacksonians on national issues apart from slavery, and Birney himself accepted the Democratic nomination for a seat in the Michigan Legislature while running as the Liberty candidate for president. Reinhard Johnson notes that most Liberty voters considered the Whigs no less proslavery that the Democrats and likely would not have voted for Clay in any case. Birney's result in 1844 was consistent with or slightly reduced from the Liberty Party's showing in the 1843 state elections, suggesting ex-Whig support for Birney represented voters who had abandoned Clay long before the 1844 campaign.[26]

Birney's defeat reopened the debate over strategy that had troubled the party in 1843. While Birney improved substantially on his result from 1840, his showing compared less favorably to more recent Liberty Party performances in state and local elections. Birney had damaged his credibility by accepting the Democratic nomination for the Michigan Legislature, which allowed Whigs to portray him as a stooge for the Democrats. In the aftermath of the election, Chase and Bailey redoubled their calls for cooperation among antislavery men of all parties. This strategy was most successful in New Hampshire, where in 1846 a coalition of antislavery Whigs, Democrats, and Liberty men won a majority in the legislature. They elected Hale to the United States Senate, where he served as an Independent Democrat. Another group, including Smith and William Goodell, continued to eschew cross-party cooperation. Instead, they proposed that the Liberty Party should embrace other popular reform causes in order to appeal to a broader swath of the electorate. This group organized the Liberty League to promote their platform and candidates within the Liberty Party. The core disagreement between these two groups was whether Liberty members should consider themselves a "temporary" or "permanent" party. Chase, Bailey, Stanton, and Whittier saw the party as a temporary organization whose role was to initiate a political realignment, with Liberty members joining antislavery Whigs and Democrats in a new, broad-tent anti-extension party. Smith, Goodell, Leavitt, and Birney, meanwhile, insisted that the Liberty Party was a permanent project whose objective was to defeat rather than convert the two established parties.[27]

Increasingly, some Liberty members began to articulate an antislavery legal theory at odds with the accepted Garrisonian interpretation of the Constitution. Garrison, who memorably described the Constitution as "a covenant with death" and "an agreement with Hell," held it to be a proslavery document that committed the national government to slavery's defense. The 1843 Liberty platform accepted this argument in part, demanding the "divorce" of the national government from slavery, but conceding that Congress lacked the authority to abolish slavery directly. After 1844, Liberty leaders including Smith and Goodell began to argue that the Constitution was in fact antislavery and had been wrongly construed by proslavery judges and elected officials. Lysander Spooner claimed that slavery had been abolished by the Declaration of Independence and that its continuance after 1776 was unlawful.[28] The antislavery interpretation of the Constitution became a core position of the Liberty League; Chase and Bailey (who after 1847 served as the editor of The National Era) continued to assert slavery's constitutional status and the need for abolitionists to work within the system of states' rights.[29]

In June 1847, the Liberty League held a convention at Macedon, New York. The delegates nominated Smith for president and Elihu Burritt for vice president. Birney, Lydia Child, and Lucretia Mott also received votes for president.[30] The purpose of the convention was not to organize a new party, but to influence the upcoming Liberty National Convention. Meanwhile, Chase was working intently to promote Hale as the candidate likeliest to attract support from antislavery voters outside the Liberty Party. Hale was an unconventional choice for most Liberty members. Many had admired his protest against the gag rule and his opposition to the annexation of Texas. He shared many of the Liberty Party's immediate goals, including the abolition of slavery in the territories. Nevertheless, Hale was not a member of the Liberty Party, nor did he call himself an abolitionist. When the Liberty Party delegates at Buffalo voted overwhelmingly to nominate Hale over Smith, it represented a victory for Chase and the coalitionists. By nominating Hale, the delegates had chosen to fight the next campaign on the narrow ground of opposition to slavery's westward extension, rather than the broader reform agenda advocated by the Liberty League. This position had the advantage of appealing to a wider range of voters than the Liberty Party had previously been able to reach. For the Liberty Leaguers, however, this represented a retreat from the broader evangelical reform spirit that had led them into the abolitionist movement. Their opposition to slavery grew out of a comprehensive ethic of social justice that opposed all forms of inequity and oppression. By nominating Hale, the Liberty Party, in their view, had surrendered its long-term social agenda for the sake of short-term political gain.[31]

Fusion, 1847–48

The struggle between the Liberty League and the coalitionists for control of the Liberty Party occurred as events were rapidly transforming the national context for political antislavery. Following the Mexican–American War, the United States acquired a vast tract of land in the southwest comprising the present-day states of California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. Congressional efforts to organize this new territory soon became mired in controversy over the westward extension of slavery. Antislavery Whigs and Democrats united behind a proposal by David Wilmot to outlaw slavery in the entire Mexican Cession. The Wilmot Proviso easily passed the House but stalled in the Senate, where the free and slave states had equal representation. As the debate dragged on into 1848, the issue of slavery's extension promised to be the major issue in the upcoming presidential election. Once again snubbing Martin Van Buren, the Democratic National Convention nominated Lewis Cass of Michigan on a platform endorsing popular sovereignty. Clay was again a candidate for the Whigs, but the convention passed him over in favor of General Zachary Taylor. Though publicly neutral on the slavery question, Taylor was a slaveholder and a career military man who had risen to prominence in a war many northern Whigs had fervently opposed. Faced with a choice between a proslavery Democrat and a slaveholding Whig, the moment seemed ripe for a union of antislavery men of all parties like what Chase and the coalitionists had long anticipated.[32]

The Van Buren men were the first to bolt. On June 22, a mass demonstration of Barnburner Democrats in New York City summoned delegates to Utica to nominate an antislavery Democrat to run against the nominees of the two established parties. Simultaneously, Conscience Whigs anticipating the selection of a proslavery national candidate made plans to lead their voters out of the Whig tent. With the rupture of both established party coalitions seemingly imminent, Chase quickly organized a Free Territory Convention that could provide the basis for a coordinated effort by antislavery men of all parties in opposition to the nominees of the Slave Power. Events in Philadelphia soon brought these plans to fruition. Taylor secured the Whig nomination on June 9; that evening, a group of fifteen dissident Whig delegates led by Henry Wilson met and issued the long-awaited call for a new antislavery party.[33] The following day, the Utica Barnburner convention nominated Van Buren for president and Henry Dodge for vice president. When Dodge declined the vice presidential nomination, it opened the door for the Barnburners to join the emerging Free Soil coalition. Representatives of the three factions met at Buffalo on August 9, 1848, to organize the national Free Soil Party and nominate candidates for president and vice president. Approximately 20,000 men and women were in attendance at the convention, which lasted two days. Hale was still the preferred choice of most Liberty members, but the importance of the Barnburners—by far the largest element of the coalition—required Van Buren be the presidential candidate. Conscience Whig Charles Francis Adams Sr., the son of the late John Quincy Adams, was nominated for vice president. Hale promptly withdrew from the presidential race, and the large majority of the Liberty Party was subsumed into the Free Soil movement.[34]

The platform of the Free Soil Party was notably more conservative than earlier Liberty Party documents.[35] It confined itself to opposing the extension of slavery into new states and expressly denied the authority of Congress to abolish slavery where it already existed. This, so far, was consistent with the position of the Liberty Party in 1844; but the Free Soil Party rejected the racial egalitarianism of the Liberty Party and the antislavery construction of the Fifth Amendment for which Chase had argued persistently over the previous decade. It embraced traditional Democratic economic policies many in the Liberty Party had long supported, including a federal homestead act.[36] These points were wholly insufficient for the Liberty League, who revived Gerrit Smith's candidacy under the banner of the National Liberty Party. An ad hoc national convention held at Buffalo nominated Smith and Charles C. Foote on a platform embracing the radical implications of the Liberty League's "one idea" philosophy. Declaring themselves unalterably committed to the cause of human freedom and the destruction of all arbitrary distinctions of race, class, and gender, they endorsed the extension of universal suffrage, temperance, land reform, the abolition of the army and navy, and a general boycott of all consumer goods connected with slavery. They praised the heroism of the French utopian socialists and the 77 enslaved men and women who had recently staged an escape attempt in Washington, D.C.[37]

Almost all Liberty members, however, eventually followed Joshua Leavitt into the Free Soil Party. Early successes in Upper New England encouraged hopes for a political earthquake, as the Free Soilers made strong gains in the Maine and Vermont state elections ahead of November and in Vermont actually replaced the Democrats as the main opposition to the Whigs.[38] In the first presidential election to be held on the same day in every state, Van Buren received 291,000 popular votes, or slightly more than 10 percent. In three states (Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont) the Free Soil Party eclipsed the Democrats as the second-largest party.[39] Most of the new converts were former Democrats attracted by the presence of Van Buren on the top of the ticket; Johnson estimates that even if the New York Barnburners are discounted, "Democrats contributed proportionally more support than the Whigs" to the new party. Twelve Free Soilers were elected to the House of Representatives, and a coalition of Free Soilers and Democrats in Ohio elected Chase to the Senate. Downballot the party performed respectably, electing several dozen state legislators across the Upper North. The National Liberty ticket of Smith and Foote received fewer than 3,000 votes, almost all from New York. The Free Soil coalition thus spelled the death of the Liberty Party as an independent political force.[40]

Decline, 1849–60

After 1848, most of the leaders and almost all of the membership of the Liberty Party was transferred to the Free Soil Party. In the late 1850s, the Free Soilers joined other opponents of the Kansas–Nebraska Act to form the Republican Party. Chase was again instrumental in this second fusion effort and was a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 1860.[41] A remnant of the Liberty League led by Smith and Goodell persisted under various names and continued to field candidates as late as 1860. Smith was a delegate to the 1852 Free Soil National Convention in Pittsburgh; in an open letter "to the Liberty Party of the County of Madison," he declared that while the platform adopted by the Pittsburgh convention was lacking in certain respects, most notably in its failure to declare slavery unconstitutional, "I, nevertheless, regard myself as a member of that party. It is a good party—and it will, rapidly, grow better." He urged the Liberty Party not to disband, but to maintain a separate organization in hopes of reforming the Free Soil Party through outside pressure.[42] When the Liberty Party met in convention at Canastota, New York later that year, Smith opposed the effort to nominate a separate presidential ticket and proposed instead that the party should endorse the Free Soil ticket of Hale and George Washington Julian. Smith's motion carried by a vote of 55–41, whereupon the convention adjourned until October 1; the minority remained behind and nominated Goodell for president and Charles C. Foote for vice president.[43] No votes were recorded for Goodell in any state, but Smith was elected to Congress from New York's 22nd congressional district as an independent antislavery candidate.[44][lower-alpha 1]

Smith was nominated for president by the National Abolition Convention in 1856; Samuel McFarland was nominated for vice president.[45] The pair received 321 popular votes, all from New York and Ohio.[46] Smith made his final bid for the presidency in 1860 as the Radical Abolitionist nominee; once again, McFarland was the party's vice presidential candidate.[47] They received 176 votes in three states: 35 from Illinois, five from Indiana, and 136 from Ohio.[48] The 1860 election was won by Abraham Lincoln, who went on to serve as president during the American Civil War. In later years, Smith along with Frederick Douglass and other members of the Liberty League would join Lincoln's Republican Party, driving the party to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment and to support the rights of freed people during Reconstruction.

Electoral history

Presidential tickets

| Election | Ticket | Electoral results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presidential nominee | Running mate | Popular vote | Electoral votes | Ranking | |

| 1840 | James G. Birney | Thomas Earle | 0.29% | 0 / 294 |

3 |

| 1844 | James G. Birney | Thomas Morris | 2.30% | 0 / 275 |

3 |

| 1848 | Gerrit Smith[lower-alpha 2] | Charles C. Foote[lower-alpha 3] | 0.10% | 0 / 290 |

4 |

| 1852 | William Goodell | Charles C. Foote | —[lower-alpha 4] | 0 / 296 |

n/a |

| 1856 | Gerrit Smith | Samuel McFarland | 0.00% | 0 / 296 |

4 |

| 1860 | Gerrit Smith | Samuel McFarland | 0.00% | 0 / 303 |

5 |

Other prominent Liberty Party members

- James Appleton, Maine state legislator and Liberty Party nominee for Governor (1842)

- Henry Bibb, former slave who campaigned for the Liberty Party in Michigan

- Salmon P. Chase, Liberty Party organizer later involved in founding the Free Soil and Republican parties

- Shepard Cary, Democratic member of Congress from Maine and Liberty Party nominee for Governor (1854)

- Charles Durkee, Wisconsin legislator and Congressman who moved on to the Free Soil party and then to U.S. Senator as a Republican

- Samuel Fessenden, co-founder of the Republican Party and Liberty Party nominee for Maine Governor (1847)

- Henry Highland Garnet, religious leader and Liberty Party organizer in New York

- Ezekiel Holmes, Maine state legislator and two-time Liberty Party nominee for Governor

- Abby Kelley, who spoke at the Liberty Party convention (1843), becoming the first American woman to address a national political convention

- Rufus Lumry, 1844 Liberty Party candidate for the Illinois state legislature, circuit preacher and early Illinois organizer of the abolitionist Wesleyan Methodist Church

- Samuel Ringgold Ward, abolitionist speaker and Liberty Party organizer

Notes

- ↑ Although he was not a candidate, Smith received 72 votes for president in New York.

- ↑ Replacing John P. Hale

- ↑ Replacing Leicester King

- ↑ Gerrit Smith received 72 votes in New York as an Abolitionist candidate. No votes were recorded for the Goodell/Foote ticket.

- ↑ Johnson, Reinhard O. (2009). The Liberty Party 1840-48: Antislavery Third Party Politics in the United States. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 7–11. ISBN 9780807133934.

- ↑ Robertson, Stacey M. (2010). Hearts Beating for Liberty: Women Abolitionists in the Old Northwest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 9780807834084.

- ↑ Johnson, 65-70.

- ↑ Johnson, 77-81.

- ↑ Johnson, 86-87.

- ↑ Proceedings of the National Liberty Convention. Utica, NY: S.W. Green. 1848. pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Johnson, 10–11.

- ↑ Earle, Jonathan H. (2004). Jacksonian Antislavery and the Politics of Free Soil, 1824-1854. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 46, 86. ISBN 0-8078-5555-3.

- ↑ Holt, Michael F. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-19-516104-1.

- ↑ Johnson, 15–17.

- ↑ Dubin, Michael J. (2002). United States Presidential Elections, 1788-1860. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-7864-6422-7.

- ↑ Johnson, 16.

- ↑ Howe, David Walker (2007). What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 677–680. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7.

- ↑ Johnson, 26.

- ↑ Johnson, 47-48.

- ↑ Johnson, 27–30.

- ↑ Johnson, 31-32.

- ↑ Johnson, 34–37.

- ↑ Frederick, J. M. H. (1896). National Party Platforms of the United States. Akron, Ohio. pp. 14–16.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Dubin, 83.

- ↑ Earle, 63.

- ↑ Howe, 180.

- ↑ Jordan, Ryan (Spring 2000). "The Indiana Separation and the Limits of Quaker Antislavery". Quaker History. 89 (1): 2.

- ↑ Gac, Scott (2007). Singing for Freedom: The Hutchinson Family Players and the Nineteenth-Century Culture of Reform. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 249–51.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Soren (Fall 2015). "Conviction and Circumstance: The Liberty Party in Indiana". Earlham Historical Journal. 8 (1): 9.

- ↑ Johnson 43; 47.

- ↑ Johnson, 46; 44; 65-70.

- ↑ Spooner, Lysander (1845). The Unconstitutionality of Slavery. Boston. p. 42.

- ↑ Johnson, 56–61.

- ↑ "Liberty League". Niles' National Register. 22 (19): 296. July 10, 1847.

- ↑ Johnson, 65; 77; 81–82.

- ↑ Johnson, 82–83.

- ↑ Holt, 333-334.

- ↑ Johnson, 83-87.

- ↑ Johnson, 85.

- ↑ Frederick, J.M.H. (1896). National Party Platforms of the United States. Akron, OH. pp. 19–20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Proceedings of the National Liberty Convention. Utica, NY: S.W. Green. 1848. pp. 6–9.

- ↑ Johnson, 88–89.

- ↑ Dubin, 96.

- ↑ Johnson, 89-91.

- ↑ Foner, Eric (1991). Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-19-509497-8.

- ↑ Smith, Gerrit (September 4, 1852). "Gerrit Smith and the Pittsburgh Platform". Anti-Slavery Bugel.

- ↑ "Liberty Convention". The National Era. September 9, 1852.

- ↑ Dubin, 128; Johnson, 91.

- ↑ "National Abolition Convention". The National Era. June 26, 1856.

- ↑ Dubin, 158.

- ↑ "Radical Abolition National Convention". Douglass' Monthly. October 1860.

- ↑ Dubin, 159.

References

- "Correspondence of the Era - General Liberty Conference at Buffalo". The National Era. Washington, D.C.: Buell & Blanchard, Printers. 1 (43). 1847.

- Smith, Gerritt (1848). Proceedings of the National Liberty Convention, held at Buffalo, N.Y. Portland, ME: Brown Thurston. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- Willey, Austin (1886). The history of the antislavery cause in state and nation. B. Thruston.

- National Party Conventions 1831–1972 (1976). Rhodes Cook. Congressional Quarterly. ISBN 0-87187-093-2.

Further reading

- Julian P. Bretz. "The Economic Background of the Liberty Party". American Historical Review. vol. 34. no. 2 (January 1929). pp. 250–264. In JSTOR

- Brooks, Corey M. (2016). Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226307282.

- Reinhard O. Johnson (2009). The Liberty Party, 1840–1848: Antislavery Third-Party Politics in the United States. Baton Rouge, LA. Louisiana State University Press.

- R.L. Morrow, "The Liberty Party in Vermont". New England Quarterly. vol. 2. no. 2 (April 1929). pp. 234–248. In JSTOR.

- Edward Schriver, "Black Politics without Blacks: Maine 1841-1848". Phylon. vol. 31. no. 2 (1970, Q-II). pp. 194–201. In JSTOR.

- Richard H. Sewell, "John P. Hale and the Liberty Party, 1847-1848". New England Quarterly. vol. 37. no. 2 (June 1964). pp. 200–223. In JSTOR.

- Ray M. Shortridge, "Voting for Minor Parties in the Antebellum Midwest". Indiana Magazine of History. vol. 74. no. 2 (June 1978). pp. 117–134. In JSTOR.

- Smith, Theodore Clarke (1897). The Liberty and Free Soil Parties in the Northwest. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Charles H. Wesley, "The Participation of Negroes in Anti-Slavery Political Parties". Journal of Negro History. vol. 29. no. 1 (January 1944). pp. 32–74. In JSTOR.

- Vernon Volpe (1990). Forlorn Hope of Freedom: The Liberty Party in the Old Northwest, 1838-1848. Kent, OH. Kent State University Press.

External links

- The Liberator Files – items concerning the Liberty Party from Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.