Lihyanite Kingdom مملكة لحيان | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7th century BC–24 BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Capital | Dedan | ||||||

| Common languages | Dadanitic | ||||||

| Religion | North Arabian polytheism | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| King | |||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||

• Established | 7th century BC | ||||||

• annexed by the Nabataean state | 24 BC | ||||||

| |||||||

| Historical Arab states and dynasties |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

Lihyan (Arabic: لحيان, Liḥyān; Greek: Lechienoi),[1] also called Dadān or Dedan, was a powerful and highly organized ancient Arab kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula and used Dadanitic language.[2] The Lihyanites ruled over a large domain from Yathrib in the south and parts of the Levant in the north.[3] In antiquity, the Gulf of Aqaba used to be called Gulf of Lihyan. A testimony to the extensive influence that Lihyan acquired.[4] The term "Dedanite" usually describes the earlier phase of the history of this kingdom since their capital name was Dedan, which is now called Al-'Ula oasis located in northwestern Arabia, some 110 km southwest of Teima, both cities located in modern-day Saudi Arabia, while the term "Lihyanite" describes the later phase. Dadan in its early phase was "one of the most important caravan centers in northern Arabia".[5] It is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.[5] The Lihyanites later became the enemies of the Nabataeans. The Romans invaded the Nabataeans and acquired their kingdom in 106 AD. This encouraged the Lihyanites to establish an independent kingdom to manage their country. This was headed by the King Han'as, one of the former royal family, which governed Al-Hijr before the Nabataean Expansion.

Terminology

The term Dedan (ddn) appears in ancient texts exclusively as a toponym (name of a place), while the term Lihyan (lḥyn) appears as both a toponym and an ethnonym (name of a people). Dedan appears originally to have referred to the mountain of Jabal al-Khuraybah. In Minaic inscriptions the two terms appear together with the former indicating a place and the latter a people. Nonetheless, in modern historiography the terms are often employed with a chronological meaning, Dedan referring to the earlier period and Lihyan the later of the same civilization.[6][7]

The adjectives "Dedanite" and "Lihyanite" were often used in the past for the Dadanitic language and script, but they are now most often used in an ethnic sense on analogy with the distinction between "Arab" and "Arabic".[8]

Dadān represents a best approximation of the original pronunciation, while the more traditional spelling Dedan reflects the form found in the Hebrew Bible.[9]

History

Timeline

Scholars have long grappled to establish a reliable timeline for the kingdoms of Lihyan and Dadan; numerous attempts were made to construct a secure chronology, but none of them so far came to fruition.[10] This important chapter in the region's history remains fundamentally obscured. The main source of information regarding the date of the Lihyanite kingdom emanates from the collection of inscriptions within the precinct of Dadān and its contiguous environs.[11] Thus, when attempting to piece together the history of the kingdom, previous historians have heavily relied on epigraphic records and sometimes scant archaeological remains due to the lack of comprehensive excavations. The absence of specific references to well-dated external events in these local inscriptions has made it challenging to establish a definitive and uncontested chronology.[11] In the pursuit of a resolution, two notable chronologies were formulated: a short one proposed by W. Caskel, now discarded in contemporary scholarship, and a longer chronology put forward by F. Winnett, which is widely adopted despite the acknowledged chronological dearth.

In his long chronology, F. Winnett agrees with Caskel that the Lihyanites succeeded an earlier, lesser-known local dynasty whose members were referred to as ‘king of Dadān’, which he places its beginning in the 6th century BC. The Lihyanites, on the other hand, appeared in the 4th century BC and disappeared in the 2nd century BC.[12] To date the beginning of the Lihyanite kingdom, a key inscription discovered north of Dadān is widely considered, which reads: nrn bn ḥḍrw t(q)ṭ b-ʾym gšm bn šhr wʿbd fḥt ddn brʾ[y]... (lit. ' Nīrān b. Ḥāḍiru inscribed his name in the days of Gashm b. Shahr and ʿbd the governor of Dadān, in the reig[n of]...').[11] Notably, the inscription likely concluded with the name of a king, under whom Gashm b. Shahr and ʿAbd held their positions.[13] Significantly, Winnett observed that the text references a governor (fḥt) of Dadān, without any mention of Lihyan, indicating that the Lihyanite kingdom did not exist at that time,[11] given that Dadān is widely considered the capital of their realm.[14] Moreover, based on the appearance of the word fḥt (from Aramaic pḥt; lit. ' governor'), which is understood as a title known only from the time of the Achaemenid empire,[15] the inscription was dated by Winnett to the Achaemenid period[11] and interpreted to be an allusion for a Qedarite rule over Dadān and elsewhere in northern Arabia as agents of the Achaemenid administration in the region.[16] Winnett identified Gashm b. Shahr with Geshem the Arab who opposed Nehemiah's reconstruction of Jerusalem in 444 BC and accordingly narrowed the dating of the text to the second half of the fifth century BC. Later scholars supported this dating by equating both Dadanitic Gashm and Biblical Geshem with Geshem, father of Qainū king of Qedar, who is mentioned on a votive bowl from Tall al-Maskhūṭah, in Sinai, dated around c. 400 BC.[17] If we accept these two main assumptions — the interpretation and tentative dating of the text to the Achaemenid period and the equation of Gashm b. Shahr with Geshem the Arab and Geshem father of Qainū — then we have a likely limit in the second half of the fifth century BC after which the Lihyanites must have emerged as an independent kingdom,[11] possibly due to the fragmentation of the Qedarite realm.[18] Such assumptions, however, are tenuous; for Achaemenid presence in northern Arabia is more difficult to ascertain since pḥt is shown to be used in Aramaic well before the Achaemenid period and was customary for regional governors in the Assyrian empire centuries prior.[18] This fḥt could very well be a Qedarite governor of Dadān on behalf of the Neo-Babylonian ruler Nabonidus after the kings of both Taymāʾ and Dadān were slain in his enigmatic Arabian campaign (c. 552 BC).[19] Indeed, only during Nabonidus' brief tenure in Tayma was the Hijaz explicitly under foreign control. It is in this time when the Aramaic term pḥt was likely introduced for officials in the region.[18] As for the latter assumption, it has been criticised by several scholars, pointing out the frequent use of the name gšm in northern Arabia does not warrant this identification.[11]

Overall, what we can discern is that the Lihyanite kingdom most likely came into being after the arrival of Nabonidus in north-west Arabia in 552 BC, as 'king of Dadān' is still mentioned during his Arabian campaign.[11] Although no more precise terminus post quem can be provided to us by the Dadanitic inscriptions, they do grant us, however, the means to estimate the minimum duration of the Lihyanite kingdom.[11] This estimation can be arrived at by simply summing the regnal years of all the 'kings of Lihyan' mentioned in the Dadanitic corpus. At present, our knowledge encompasses at least twelve such kings with a combined reign spanning 199 years.[11] Consequently, this calculation establishes a terminus post quem for the kingdom's end. If we establish that the kingdom could not have come into existence before 552 BC, it logically follows that its downfall could not have transpired before 353 BC. Therefore, the earliest conceivable time range for the kingdom of Lihyan falls between the mid-sixth and the mid-fourth centuries BC.[20]

Stages

.jpg.webp)

Situated in Wadi al-Qura within modern al-ʿUla, al-Khuraybah is believed to be ancient Dadān[21]—a significant hub of culture and commerce in ancient northwest Arabia. It thrived in the 1st millennium BC, fostering through the development of long-distance trade along the ‘Incense Road,’ acting as an important and strategic trade link connecting ancient South Arabia with Egypt, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. Dadān served as the capital for two successive kingdoms: the local kingdom of Dadān, in the early/mid-1st millennium BC, and the larger kingdom of Lihyan, which ruled over a broader domain in northwest Arabia.[22] Biblical accounts refer to Dadān as early as the sixth century BC, mentioning its ‘caravans’ and ‘saddlecloth’ trade.[23] At this time, Dadān is a place of undoubted significance, as it was also mentioned by Nabonidus in his Arabian campaign,[24] where he claimed to have defeated ‘king of Dadān’ (šarru ša Dadana). However, neither the king’s identity nor how Nabonidus dealt with him are known. It’s plausible that he had him killed as he did to it-ta-a-ru (Yatar), king of Taymāʾ.[25] Only few Dadanite kings are known—two funerary inscriptions of interest are that of Kabirʾil b. Mataʿʾil, who is called ‘king of Dadān’ (mlk ddn), and Mataʿʾil b. Dharahʾil, who may have been his father.[26] It’s possible that Kabirʾil inherited his position from his father Mataʿʾil, in a dynastic tradition of paternal succession. While Mataʿʾil was not explicitly referred to as ‘king of Dadān’, a Dadanitic inscription found on the top of Ithlib mountain asks for the protection of both Mataʿʾil and Dadān by a man named Taim b. Zabīda, suggesting his likely kingship.[27] A recent discovery of Dadanitic inscription found in a secondary context near the main temple at al-Khuraybah introduces another king, ‘ʿĀṣī, king of Dadān’ (ʿṣy mlk ddn), and has a dedication to a deity named Ṭaḥlān.[28] ʿĀṣī might have been the son of Mataʿʾil and the brother of Kabirʾil.[25] These internal and external sources were taken as an indication of the existence of a “well-organized state” in the region before the mid-1st millennium BC.[29]

Despite weighty chronological challenges, it’s evident that the kingdom of Dadān was succeeded in al-ʿUla by the kingdom of Lihyan.[30] It is not clear, however, when this transition occurred.[23]

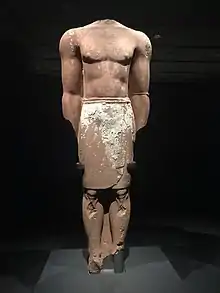

It appears, from recent epigraphic publications, that Lihyan controlled their trade rival Tayma (a fertile and rich oasis in North Arabia) for several generations.[31] The hostility between the two oases is reflected by an inscription from Tayma that mention a war between them. After the Lihyanite annexation of Tayma, the Lihyanite kings may have visited the city to commemorate their rule on regular basis. Indeed, standing statues larger than human stature with legs aligned and hands hanging down, supposedly of Lihyanite kings, were found in the temple of Tayma, probably as a reminder to the population of subordination to the king of Dedan. The statues correspond with similar royal statues from Dedan, which display a standardized artistic model of dignitary sculpting. Thus suggesting the role of Dedan as a regional power.[31] In the Biblical records, Dedan is mentioned alongside Tayma and Saba, but more often connected with Qedar. The kings of Lihyan were possibly the descendants of the Qedarites,[32] and had close contacts with the Ptolemaic dynasty.

The oldest reference to Lihyan (lḥyn) comes from early Sabaean inscription dated to the first half of the sixth century BC that records the journey of a Sabaean merchant. He intended to go to Cyprus for trade, and on his way he passed through Dedan, the "cities of Judah", and Gaza.[33]

Fall

Some authors assert that the Lihyanites fell into the hands of the Nabataeans around 65 BC upon their seizure of Hegra then marching to Tayma, and finally to their capital Dedan in 9 BC. Werner Cascel suggests that the Nabataean annexation of Lihyan was around 24 BC; this is based on two factors. The first, Cascel relied on Strabo's accounts of the disastrous Roman expedition on Yemen that was led by Aelius Gallus from 26 to 24 BC. Strabo made no mention of any independent polity called Lihyan. The second is an inscription which mentions the Nabataean king Aretas IV found on a tomb in Hegra (dated around 9 BC). It suggests that the territories of Lihyan were already conquered by the Nabataeans under his reign (that of Aretas IV.) Nearly half a century later, an inscription from a certain Nabataean general who used Hegra as his HQ mentions the installation of Nabataean soldiers in Dedan the capital of Lihyan.

The Nabataean rule over Lihyan ended with the annexation of Nabatea by the Romans in 106 AD. Although the Romans annexed most of the Nabataean Kingdom, they did not however reach the territories of Dedan. The Roman legionaries that escorted the caravans stopped 10 km before Dedan, the former boundary between Lihyan and Nabatea. The Lihyanites restored their independence under the rule of Han'as ibn Tilmi, a member of the former royal family that predated the Nabataean invasion. His name is recorded by a craftsman who dated his tomb by carving the fifth year of Han'as ibn Tilmi reign.

Governance

The term "king of Dedan" (mlk ddn) occurs three times in surviving inscriptions, along with the phrases governor (fḥt) and lord (gbl) of Dedan. The term "king of Lihyan" (mlk lḥyn) occurs at least twenty times in Dadanitic inscriptions.[7]

The Lihyanite kingdom was a monarchy that followed a heredity succession system. The kingdom's bureaucracy represented by the Hajbal members, similar to the people's council in our modern time, used to aid the king in his daily duties and took care of certain state affairs on behalf of the king.[34] This public nature of the Lihyanite legal system is shared with that of south Arabia.[35]

The Lihyanite rulers were of great importance in the Lihyanite society, as religious offerings and events were generally dated according to the years of king reign. Sometimes regnal titles were used; such as Dhi Aslan (King of the Mountains) and Dhi Manen (Robust King).[36] Also religion played a significant role and was, along with the king, a source of legislation. Under the king there was a religious clergy headed by the Afkal, which appears to be inherently passed position.[37] The term was borrowed by the Nabataeans directly from the Lihyanites.[38]

Other state occupations that were recorded in Lihyanite inscriptions was the position of Salh (Salha for a female); mostly occurs before the name of the supreme Lihyanite deity Dhu-Ghabat (meaning the delegate of Dhu-Ghabat). The Salh was responsible for collecting taxes and alms from the followers of the god.[39] Tahal (a share of the taxes) which equals one tenth of the riches was dedicated to the deities.[40]

Post-Nabataean Lihyanite kings were less powerful in comparison to their former predecessors, as the Hajbal exercised greater influence on the state, to the point where the king was virtually a figurehead and the real power was held by the Hajbal.[41]

Economy

Dedan was a prosperous trading centre that lay along the north–south caravan route at the northern end of the Incense Road. It hosted a community of Minaeans.[9]

According to Ezekiel, in the 7th century Dedan traded with Tyre, exporting saddle cloths.[42]

Religion

The Lihyanites worshipped Dhu-Ghabat and rarely turned to other deities for their needs. Other deities worshipped in their capital Dedan included the god Wadd, brought there by the Minaeans, and al-Kutba'/Aktab, who was probably related to a Babylonian deity and was perhaps introduced to the oasis by the king Nabonidus.[43]

See also

References

- ↑ "Liḥyān - ANCIENT KINGDOM, ARABIA". Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ↑ Rohmer & Charloux 2015, p. 297.

- ↑ Saudi Arabia Tourism Guide

- ↑ Discovering Lehi. Cedar Fort; 9 August 1996. ISBN 978-1-4621-2638-5. p. 153.

- 1 2 Parr 1997.

- ↑ Farès-Drappeau 2005, p. 30.

- 1 2 Hidalgo-Chacón Díez 2015, p. 141.

- ↑ Hidalgo-Chacón Díez & Macdonald 2017, p. vii.

- 1 2 Macdonald 2018, p. 1.

- ↑ Macdonald 2019, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rohmer & Charloux 2015, p. 299.

- ↑ Farès-Drappeau 2005, p. 113.

- ↑ Ephʻal 1982, p. 204.

- ↑ Rohmer 2021, p. 182.

- ↑ Fahd 1989, p. 51.

- ↑ Graf 2019, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Rohmer 2021, p. 181.

- 1 2 3 Graf 2019, p. 23.

- ↑ Graf 2019, p. 24.

- ↑ Rohmer & Charloux 2015, pp. 299–300.

- ↑ Hausleiter 2012, p. 826—827.

- ↑ Rohmer, Grégor & Alsuhaibani 2023, p. 178.

- 1 2 Hoyland 2002, p. 66.

- ↑ Hausleiter 2012, p. 824.

- 1 2 Al‐Said 2011, p. 199.

- ↑ Potts 2010, p. 44.

- ↑ Al‐Said 2011, p. 198.

- ↑ Al‐Said 2011, p. 196—197.

- ↑ Hausleiter 2012, p. 827.

- ↑ Potts 2010, p. 45.

- 1 2 Hausleiter 2012, p. 825.

- ↑ Cross, A New Aramaic Stele from Tayma, p.392

- ↑ Rohmer & Charloux 2015, p. 302.

- ↑ Thomas Kummert: (Dedan - Khuraibah) Early Ancient Kingdom and Trading Oasis on Incense Route - p.2

- ↑ Werner Caskel on Ancient Lihyan p.4

- ↑ نقوش لحيانية من منطقة العلا د. حسين بن علي p.328

- ↑ Jawad Ali: The history of the Arabs before Islam - p. 425

- ↑ Healey, J. 1993: p.36-37

- ↑ نقوش لحيانية من منطقة العلا د. حسين بن علي p. 326-327

- ↑ Roads of Arabia p.272

- ↑ Jawad Ali: The history of the Arabs before Islam - p. 338

- ↑ Macdonald 1997, p. 341.

- ↑ Hoyland 2002, p. 141.

Sources

- Rohmer, J.; Grégor, Th.; Alsuhaibani, A. (2023). "Quarrying, Carving and Shaping the Landscape: Stone Working at Dadan, Northwest Arabia, in the First Millennium BCE and Beyond". In Lamesa, A.; Whitaker, K.; Sciuto, C.; Porqueddu, M.E.; Gattiglia, G. (eds.). From Quarries to Rock-cut Sites: Echoes of Stone Crafting. Sidestone Press. pp. 177–197. ISBN 978-94-6426-164-6.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2010). "The Arabian Peninsula, 600 BCE to 600 CE". In Huth, Martin; G. Van Alfen, Peter (eds.). Coinage of the Caravan Kingdoms: Studies in the Monetization of Ancient Arabia. Numismatic Studies. Vol. 1. American Numismatic Society. pp. 27–64. ISBN 978-0-89722-312-6.

- Al‐Said, Said F. (2011). "Recent epigraphic evidence from the excavations at Al‐ʿUla reveals a new king of Dadān". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. Wiley. 22 (2): 196–200. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2011.00343.x. ISSN 0905-7196.

- Graf, D.F. (2019). Rome and the Arabian Frontier: From the Nabataeans to the Saracens. Routledge Revivals. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-78455-2. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- Fahd, T. (1989). L'Arabie préislamique et son environnement historique et culturel: actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 24-27 juin 1987. Travaux du Centre de Recherche Sur le Proche-Orient et la Grece Antiques de l'Universite Es Sciences Humaines de Strasbourg Series (in French). Distribution par E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09115-3. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- Schwab, A.; Schütze, A. (2023). Herodotean Soundings: The Cambyses Logos. Classica Monacensia. Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8233-0391-6. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- Ephʻal, I. (1982). The Ancient Arabs: Nomads on the Borders of the Fertile Crescent, 9Th-5Th Centuries B.C. Magnes Press, Hebrew University. ISBN 978-965-223-400-1. Retrieved 2023-10-24.

- Macdonald, Michael C. A. (2019). "Liḥyān". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Stewart, Devin J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. pp. 131–134. ISBN 978-90-04-38666-2.

- Rohmer, Jérôme (2021). "The Political History of North-west Arabia from the 6th to the 1st Century BCE: New Insights from Dadān, Ḥegrā and Taymāʾ". In Luciani, Marta (ed.). The Archaeology of the Arabian Peninsula 2. Connecting the Evidence. Oriental and European Archaeology. Vol. 19. Vienna, Austria: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 179–198. ISBN 978-3-7001-8630-4.

- Al-Ansary, Abdul-Raman T. (1999). "The State of Lihyan: A New Perspective". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 9 (1): 191–195.

- Drewes, A. J. & Levi Della Vida, G. (1986). "Liḥyān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume V: Khe–Mahi (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 761–763. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Farès-Drappeau, Saba (2005). Dédan et Liḥyān. Histoire des Arabes aux confins des pouvoirs perse et hellénistique (IVe–IIe s. avant l'ère chrétienne). Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux.

- Hidalgo-Chacón Díez, María del Carmen (2015). "The Distribution of the Dadanitic Inscriptions According to Their Content and Palaeographical Features". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 45: 139–148. JSTOR 43783628.

- Hidalgo-Chacón Díez, María del Carmen; Macdonald, Michael C. A., eds. (2017). The OCIANA Corpus of Dadanitic Inscriptions: Preliminary Edition (PDF). Oxford University Press.

- Hausleiter, Arnulf (2012). "North Arabian Kingdoms". In Daniel T. Potts (ed.). A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 2. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 816–832.

- Hoyland, Robert G. (2002). Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam. Routledge. ISBN 9781134646340.

- Macdonald, Michael C. A. (1997). "Trade Routes and Trade Goods at the Northern End of the 'Incense Road' in the First Millennium B.C.". In Alessandra Avanzini (ed.). Profumi d'Arabia: Atti del Convegno. Rome: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider. pp. 333–349.

- Macdonald, Michael C. A. (2018). "Towards a Re-assessment of the Ancient North Arabian Alphabets Used in the Oasis of al-ʿUlā". In M. C. A. Macdonald (ed.). Languages, Scripts and Their Uses in Ancient North Arabia. Archaeopress. pp. 1–19.

- Parr, Peter J. (1997). "Dedan". In Eric M. Meyers (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 133–134.

- Rohmer, Jérôme; Charloux, Guillaume (2015). "From Liḥyān to the Nabataeans: Dating the End of the Iron Age in Northwestern Arabia". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 45: 297–320.

Further reading

- Lozachmeur, H (ed.) 1995. Présence arabe dans le croissant fertile avant l'Hégire. (Actes de la table ronde internationale Paris, 13 Novembre 1993). Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations. pp. 148. ISBN 2-86538-254-0.

- Werner Caskel, Lihyan und Lihyanisch (1954)

- F.V. Winnett "A Study of the Lihyanite and Thamudic Inscriptions", University of Toronto Press, Oriental Series No. 3. Archived 2018-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Lynn M. Hilton, Hope A. Hilton (1996) "Discovering Lehi". Cedar Fort. ISBN 1462126383.