| Part of a series on |

| Ali |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

Ali ibn Abi Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib (Arabic: عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب بْن عَبْد ٱلْمُطَّلِب, romanized: ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ibn ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib; c. 600–661 CE) was the fourth and last caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruling from 656 to 661. A close companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, he is considered by Shia Muslims to be the first Imam, the rightful religious and political successor to Muhammad. The issue of succession caused a major rift among Muslims and divided them into two major branches: Shia following an appointed hereditary leadership among Ali's descendants, and Sunni following political dynasties. Ali's assassination in the Grand Mosque of Kufa by a Kharijite coincided with the rise of the Umayyad Caliphate. The Imam Ali Shrine and the city of Najaf were built around Ali's tomb and it is visited yearly by millions of devotees.

Ali was a cousin of Muhammad. He was raised by Muhammad from the age of 5 and accepted Muhammad's claim of divine revelation by age 11, being among the first to do so. Ali played a pivotal role in the early years of Islam while Muhammad was in Mecca and under severe persecution. After Muhammad's relocation to Medina in 622, Ali married his daughter Fatima, becoming Muhammad's son-in-law. Ali fathered, among others, Hasan and Husayn, the second and third Shia Imams.

Muhammad called him his brother, guardian and successor, and he was the flag bearer in most of the wars and became famous for his bravery. On his return from the Farewell Pilgrimage, Muhammad uttered the phrase, "Whoever I am his Mawla, this Ali is his Mawla." But the meaning of Mawla became disputed. Shias believed that Ali was appointed by Muhammad to lead Islam, and Sunnis interpreted the word as friendship and love. While Ali was preparing Muhammad's body for burial, a group of Muslims met and pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr. Ali pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr, after six months, but did not take part in the wars and political activity, except for the election of Uthman, the third caliph. However, he advised the three caliphs in religious, judicial, and political matters.

Following Uthman's assassination, Ali was elected caliph in Medina, which coincided with the first civil wars between Muslims. Ali faced two separate opposition forces: a group in Mecca, who wanted to convene a council to determine the caliphate; and another group led by Mu'awiya in the Levant, who demanded revenge for Uthman's blood. He defeated the first group; but in the end, the Battle of Siffin led to an arbitration that favored Mu'awiya, who eventually defeated Ali militarily. Slain by the sword of Ibn Muljam Moradi, Ali was buried outside the city of Kufa. In the eyes of his admirers, he became an example of piety and un-corrupted Islam, as well as the chivalry of pre-Islamic Arabia. Several books are dedicated to his hadiths, sermons, and prayers, the most famous of which is Nahj al-Balagha.

Birth and early life

Ali was born to Abu Talib[lower-alpha 13] and his wife Fatima bint Asad around 600 CE,[4] possibly on 13 Rajab,[5][1] which is the date celebrated annually by Shia Muslims.[6] Ali may have been the only person born inside Kaaba,[1][5][4] the holiest site of Islam, located in Mecca, present-day Saudi Arabia. Ali's father was a leading member of the Banu Hashim, a clan within the Meccan tribe of Quraysh.[5] He also raised his nephew Muhammad after his parents died. Later when Abu Talib fell into poverty, Ali was taken in at the age of five by Muhammad and raised by him and his wife Khadija.[1]

In 610,[1] aged between nine and eleven,[4] Ali was among the first to accept the teachings of Muhammad and profess Islam. Ali did so either after Khadija or after Khadija and Muhammad's successor, Abu Bakr. This order is a point of contention between Shia and Sunni scholars.[7] The earliest sources, however, seem to place Ali before Abu Bakr,[4] whose status after Muhammad's death as the first caliph might have been reflected into some Islamic records.[8][9] Muhammad's call to Islam in Mecca lasted from 610 to 622, during which Ali provided for the needs of the Meccan Muslims, especially the poor.[1] Some three years after his first revelation,[10] Muhammad gathered his relatives for a feast, invited them to Islam, and asked for their assistance.[11] Ali was the only relative who offered his support, after which Muhammad told his guests that Ali was his brother, his trustee, and his successor,[4] according to the Sunni historian al-Tabari (d. 923).[11][4] The Shia interpretation of this incident is that Muhammad had already designated Ali as his successor from an early age.[11][12]

From migration to Medina to Muhammad's death

In 622, when tipped off about an assassination plot, Muhammad escaped to Yathrib, now known as Medina, as Ali stayed behind as decoy.[1][13] This incident marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar (1 AH) and might have been the reason for the revelation of the Quranic passage, "But there is also a kind of man who gives his life away to please God."[14][15][5] Ali also escaped Mecca after returning the goods entrusted to Muhammad there.[7] In Medina, when Muhammad paired Muslims for fraternity pacts, he selected Ali as his brother.[16] Around 623–625, Muhammad gave his daughter Fatima to Ali in marriage,[17][18] aged about twenty-two at the time.[19][1] Muhammad had earlier turned down the marriage proposals by some of his companions, notably, Abu Bakr and Umar.[20][18][21]

Event of the mubahala

A Christian envoy from Najran, located in South Arabia, arrived in Medina circa 632 and negotiated a peace treaty with Muhammad.[22][23] During their visit, the two parties also debated the nature of Jesus, human or divine.[24][25] Linked to this ordeal is verse 3:61 of the Quran,[26] which instructs Muhammad to challenge his opponents to mubahala (lit. 'mutual cursing'),[27] perhaps when the debate had reached a deadlock.[25] Even though the delegation ultimately withdrew from the challenge,[23] the majority of early reports suggest that Muhammad appeared for the occasion of mubahala, accompanied by Ali, his wife Fatima, and their two sons, Hasan and Husayn.[28][29] The inclusion of these four by Muhammad in the mubahala ritual, as his witnesses and guarantors,[30][31] must have raised their religious rank within the community.[24][32] If the word 'ourselves' in the verse is a reference to Ali and Muhammad, as Shia authors argue, then the former naturally enjoys a similar religious authority in the Quran as the latter.[33][34]

_in_honor_of_Imam_'Ali.jpg.webp)

Missions

Ali acted as Muhammad's secretary and deputy in Medina.[35][7] He was also one of the scribes tasked by Muhammad with committing the Quran to writing.[1] In 628, Ali wrote down the terms of the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, the peace treaty between Muhammad and Meccan pagans. In 630, divine orders pushed Muhammad to replace Abu Bakr with Ali for a key Quranic announcement in Mecca,[36][37] according to the canonical Sunni collection Sunan al-Nasa'i.[5] Ali also helped ensure that the Conquest of Mecca in 630 was bloodless and later removed the idols from Ka'ba.[1] In 631, Ali was sent to preach in Yemen,[1] as a consequence of which the Hamdanids peacefully accepted Islam.[13][5] Ali also resolved a blood feud between Muslims and the Banu Jadhima.[5]

Military career

Ali accompanied Muhammad in all of his military expeditions except the Tabuk expedition (630), during which he was left behind in charge of Medina.[13] The hadith of the position is linked with this occasion, "Are you not content, Ali, to stand to me as Aaron stood to Moses, except that there will be no prophet after me?" This appears in the canonical Sunni collections Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim.[38] For the Shia, the hadith signifies Ali's usurped right to succeed Muhammad.[39] In the absence of Muhammad, Ali commanded the expedition to Fadak in 628.[7][1]

Ali was renowned for his bravery on the battlefield,[16][7] and for his magnanimity towards his defeated enemies.[40] He was the standard-bearer in the Battle of Badr (624) and the Battle of Khaybar (628).[35] He vigorously defended Muhammad in the Battle of Uhud (625) and the Battle of Hunayn (630),[16][1] and Muslims' victory in the Battle of Khaybar has been attributed to his courage,[7] where he is said to have torn off the iron gate of the enemy fort.[16] Ali also defeated the pagan champion Amr ibn Abd Wudd in the Battle of the Trench in 627.[5] According to al-Tabari,[5] Muhammad reported hearing a divine voice at Uhud, "[There is] no sword but Zulfiqar [Ali's sword], [there is] no chivalrous youth (fata) but Ali."[37][1] Ali and another companion, Zubayr, apparently oversaw the killing of the Banu Qurayza men for treachery in 5 AH,[7] though the historicity of this incident has been disputed.[41][42][43]

Ghadir Khumm

On his return trip from the Farewell Pilgrimage to Mecca in 632, Muhammad halted the large caravan of pilgrims at the Ghadir Khumm and addressed them after the congregational prayer.[44] Taking Ali by the hand, Muhammad asked the crowd if he was not closer (awla) to believers than they were to themselves, which they affirmed.[45] Muhammad then declared, "He whose mawla I am, Ali is his mawla."[46][47] Musnad Ibn Hanbal, a canonical Sunni source, adds that Muhammad repeated this statement three or four more times and that Umar congratulated Ali after the sermon, "You have now become the mawla of every faithful man and woman."[48][49] Muhammad had earlier alerted Muslims about his impending death.[45][50][51][52] Shia sources describe the event in greater detail, linking the announcement to verses 5:3 and 5:67 of the Quran.[45]

With some exceptions,[53] the authenticity of the Ghadir Khumm is rarely contested,[47][54][55][56][50] as its recorded tradition is "among the most extensively acknowledged and substantiated" in classical Islamic sources.[57] The interpretation of the Ghadir Khumm, however, is a source of controversy between Sunni and Shia.[57] Mawla is a polysemous Arabic word and its interpretation in the context of the Ghadir Khumm is split along sectarian lines. Shia sources interpret mawla as 'leader', 'master', and 'patron', [58] while Sunni accounts of this sermon offer little explanation,[45] or interpret the hadith as love or support for Ali,[1][59] or substitute mawla with the word wali (of God, lit. 'friend of God').[45][50][60] Shias therefore view the Ghadir Khumm as the investiture of Ali with Muhammad's religious and political authority,[61][62][5] while Sunnis regard it as a statement about the rapport between the two men,[1][50][63] or that Ali should execute Muhammad's will.[1] Shias point to the extraordinary nature of the announcement,[59] give Quranic and textual evidence,[64][45][50] and argue to eliminate other meanings of mawla in the hadith except for authority,[65] while Sunnis minimize the importance of the Ghadir Khumm by casting it as a simple response to earlier complaints about Ali.[66] During his caliphate, Ali is known to have asked Muslims to come forward with their testimonies about the Ghadir Khumm,[67][68][69] presumably to counter challenges to his legitimacy.[70]

Life under Rashidun Caliphs

Succession to Muhammad

Saqifa

Muhammad died in 632 when Ali was in his early thirties.[71] As Ali and other close relatives prepared for the burial,[72][73] a group of the Ansar (Medinan natives, lit. 'helpers') gathered at the Saqifa to discuss the future of Muslims or to re-establish their control over their city, Medina. Abu Bakr, Umar, and another companion, Abu Ubayda, soon joined the meeting as the only representatives of the Muhajirun (Meccan converts, lit. 'migrants') at the Saqifa.[74] Those present at the Saqifa appointed Abu Bakr to leadership after a heated debate that is said to have become violent.[75] The case of Ali was also unsuccessfully brought up there in his absence.[76][77]

Clan rivalries at the Saqifa played a role in favor of Abu Bakr,[72][78] and the outcome may have been different in a broad council (shura) with Ali as a candidate.[79][80] In particular, the Quraysh tradition of hereditary succession strongly favored Ali,[81][82][83][84] while his youth probably weakened his case.[7][71] By contrast, the succession (caliphate) of Abu Bakr is often justified on the basis that he led some of the prayers in Muhammad's final days,[72][85] though the veracity and political significance of such reports have been questioned.[72][86][87]

Attack on Fatima's house

After the Saqifa meeting, Umar and his supporters took to the streets of Medina,[88] and the appointment of Abu Bakr was met with little resistance there.[85] The Banu Hashim and some companions of Muhammad soon gathered in protest at Ali's house.[89][90] Among them were Zubayr and Muhammad's uncle Abbas.[90] These protestors held Ali to be the rightful successor to Muhammad,[18][91] probably in reference to his announcement at the Ghadir Khumm.[50] Among others,[88] al-Tabari reports that Umar then led an armed mob to Ali's residence and threatened to set the house on fire if Ali and his supporters did not pledge their allegiance to Abu Bakr.[92][18][93][94] The scene soon grew violent,[88][95] but the mob retreated without Ali's pledge after his wife Fatima pleaded with them.[92]

Abu Bakr later placed a successful boycott on the Banu Hashim,[96] who eventually abandoned their support for Ali.[96][97] Most likely, Ali himself did not pledge allegiance to Abu Bakr until Fatima died within six months of her father Muhammad.[98] In Shia sources, the death (and miscarriage) of the young Fatima are attributed to an attack on her house to subdue Ali on the order of Abu Bakr.[99][18][91] Sunnis categorically reject these reports,[100] but there is evidence in their early sources that a mob entered Fatima's house by force and arrested Ali,[101][102][103] an incident that Abu Bakr regretted on his deathbed.[104][105] Likely a political move to weaken the Banu Hashim,[106][107][108][109] Abu Bakr had earlier confiscated from Fatima the rich lands of Fadak, which she considered her inheritance (or a gift) from her father Muhammad.[110][111] The confiscation of Fadak is often justified in Sunni sources with a hadith about prophetic inheritance, the authenticity of which has been doubted partly because it ostensibly contradicts Quranic injunctions.[110][112]

Caliphate of Abu Bakr (r. 632–634)

In the absence of popular support, Ali eventually accepted the temporal rule of Abu Bakr, probably for the sake of Muslim unity.[113][114][115][116] In particular, he turned down proposals to forcefully pursue the caliphate.[114][7] He nevertheless viewed himself as the most qualified candidate for leadership by virtue of his merits and his kinship with Muhammad.[117][118][119][120] Evidence suggests that Ali also considered himself as the designated successor of Muhammad.[121][68][120] In contrast with the lifetime of Muhammad,[122][123] Ali retired from public life during the caliphates of Abu Bakr and his successors, Umar and Uthman.[1][122][16] Even though Ali reputedly advised Abu Bakr and Umar on government and religious matters,[1][16] their conflicts with Ali is also well-documented,[124][125][126] but largely ignored or downplayed in Sunni sources.[127][128] Their disagreements were epitomized during the proceedings of the electoral council in 644 when Ali refused to be bound by the precedence of the first two caliphs.[123][122] In contrast, Shia sources view Ali's pledge to Abu Bakr as a (coerced) act of political expediency (taqiya).[129] The conflicts with Ali are likely magnified in Shia sources.[127]

Caliphate of Umar (r. 634–644)

In 634, on his deathbed, Abu Bakr appointed Umar as his successor.[130] Ali was not consulted about the nomination of Umar, which was initially resisted by some senior companions.[131] Ali did not press any claims this time and kept aloof from public affairs during the caliphate of Umar,[132] who nevertheless consulted Ali in certain matters.[1][133] For instance, Ali is credited with the idea of adopting the migration to Medina (hijra) as the beginning of the Islamic calendar.[13] Yet the political advice of Ali was probably ignored.[133] For example, Umar devised a state register (diwan) to distribute excess state revenues according to perceived merit,[134] but Ali held that those revenues should be equally distributed, following the precedent of Muhammad and Abu Bakr.[135][133] Ali was also absent from the strategic meeting convened by Umar near Damascus.[133] Ali did not participate in the military expeditions of Umar,[136][4] although he does not seem to have publicly objected to them.[4]

Umar opposed the combination of prophethood and caliphate in the Banu Hashim,[137][138] and he thus prevented Muhammad from dictating his will on his deathbed,[139][140][141] possibly fearing that he might expressly designate Ali as his successor.[142] Nevertheless, perhaps realizing the necessity of Ali's cooperation in his collaborative scheme of governance, Umar made limited overtures to Ali and the Banu Hashim during his caliphate.[143] For instance, he returned Muhammad's estates in Medina to his uncle and Ali, but kept Fadak and Khayber.[144] Umar also insisted on marrying Ali's daughter Umm Kulthum, to which reportedly Ali agreed with reluctance when the former enlisted public support for his demand.[145]

Election of Uthman (644)

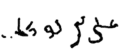

.jpg.webp)

Umar was stabbed in 644 by Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz, a disgruntled Persian slave.[146] On his deathbed, Umar tasked a small committee with choosing the next caliph among themselves.[147] Ali and Uthman were the strongest candidates in this committee,[148][149] whose members were all early companions of Muhammad from the Quraysh tribe.[147] Another member, Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf, was given the deciding vote either by the committee or by Umar.[150][151][152] After deliberations, Ibn Awf appointed his brother-in-law Uthman as the next caliph,[153][154] when the latter promised to follow the precedent of the first two caliphs.[153] By contrast, Ali rejected this condition,[153][152][155] or gave an evasive answer.[156] The Ansar were not represented in the committee,[157][151] which was evidently biased toward Uthman.[158][159][152] Both of these factors worked against Ali,[151][160][161] who could have not been simply excluded from the proceedings.[162]

Caliphate of Uthman (r. 644–656)

Uthman was widely accused of nepotism,[163] corruption,[164][165] and injustice.[166] Ali frequently criticized Uthman's conduct,[7][4][167] including his lavish gifts for his kinsmen,[168][169] and he was joined in this by most senior companions.[4][152] Ali also protected outspoken companions, such as Abu Dharr and Ammar.[170][171] Overall, Ali was likely a restraining influence on Uthman without directly opposing him.[170] Some supporters of Ali were part of the opposition to Uthman.[172][173] They were joined in their efforts by Talha and Zubayr, both senior companions of Muhammad, and by his widow A'isha.[174][175][172] Among such supporters of Ali were Malik al-Ashtar and other religiously learned qurra (lit. 'Quran readers').[176][169] These wanted to see Ali as the next caliph, though there is no evidence that he communicated or coordinated with them.[177] Ali also rejected the requests to lead the rebels,[7][178] although he probably sympathized with their grievances.[179][178] He was therefore considered a natural focus for the opposition,[180] at least morally.[7]

Assassination of Uthman (656)

As their grievances mounted, discontented groups from provinces poured into Medina in 656.[16] In their first attempt,[181] the Egyptian opposition sought the advice of Ali, who urged them to negotiate with Uthman.[182] Ali similarly asked the Iraqi opposition to refrain from violence, which they heeded.[183] More than once,[184] Ali also acted as a mediator between Uthman and the dissidents,[16][185][179] to address their economical and political grievances.[186][16] In particular, Ali negotiated and guaranteed on behalf of Uthman the promises that persuaded the rebels to return home, thus ending the first siege.[187][16] Ali then urged Uthman to publicly repent, which he did.[188] The caliph soon retracted his statement, however, possibly under the influence of his secretary Marwan ibn al-Hakam.[189] On their way back home, some Egyptian rebels intercepted an official letter ordering their punishment. They returned to Medina and laid siege to Uthman's residence for a second time, demanding that he abdicate. The caliph refused and claimed that he was unaware of the letter,[190] for which Marwan is often blamed in the early sources.[191][192] Ali sided with Uthman about the letter,[190] and suspected Marwan,[193] but a report by the Sunni historian al-Baladhuri (d. 892) suggests that the caliph accused Ali.[193] This is likely when Ali refused to further intercede for Uthman.[190][180] The caliph was assassinated soon afterward in June 656 during a raid on his residence by the Egyptian rebels.[191][194][195]

Ali played no role in the deadly attack,[7][196] and his son Hasan was injured while guarding Uthman's besieged residence at the request of Ali.[1][197][172] He also convinced the rebels to deliver water to Uthman's house during the siege.[190][170] Beyond this, historians disagree about Ali's measures to protect the third caliph.[198] Some authors highlight Ali's repeated attempts at reconciliation,[172][199][170] while others consider Ali as the immediate beneficiary of Uthman's death.[198][4] This last point has been challenged, for A'isha, whose hostility towards Ali is well-documented,[200][201][202] would have not actively opposed Uthman if Ali had been the prime mover of the rebellion and its future beneficiary.[200] Some authors commend the neutrality of Ali,[1][192][203] some speculate that he agreed with calls for Uthman's abdication,[204] and one author labels Ali as the chief culprit in the murder of Uthman, even though the evidence suggests otherwise.[205]

Caliphate

Election

When Uthman was killed in 656 by Egyptian rebels,[191] the potential candidates for caliphate were Ali and Talha. The Umayyads had fled Medina, while the provincial rebels and the Ansar were in control of the city. Among the Egyptians, Talha enjoyed some support, but the Iraqis and most of the Ansar supported Ali.[113] The (majority of the) Muhajirun,[16][178][198] and key tribal chiefs also favored Ali at this time.[206] The caliphate was offered by these groups to Ali, who, after some hesitation,[178][16][4] accepted the position following a public pledge.[207][208][209] Malik al-Ashtar might have been the first to pledge his allegiance to Ali.[209] Talha and Zubayr, who both had ambitions for the high office,[210][211] also gave their pledges to Ali, most likely willingly,[4][212][197] but later broke their oaths to him.[213][4][214] Ali probably did not force anyone to pledge,[207] and there is little evidence to support any violence, even though many broke with Ali later, claiming that they had pledged under duress.[215] At the same time, the supporters, who were the majority in Medina, might have intimidated the opposition.[216]

Legitimacy

Ali probably stepped in to prevent chaos and fill the power vacuum created by the regicide.[217][185][218] His election, irregular and without a council,[113] faced little public opposition,[196][204][217] but the rebels' support for him left him exposed to accusations of complicity in the assassination.[7] Some consider Ali the only popularly-elected caliph in Muslim history,[210][214][207] and underprivileged groups readily rallied around him.[219][210] Still, Ali had limited support among the powerful Quraysh, some of whom aspired to the title of caliph.[201][113] Within the Quraysh, two camps opposed to Ali: the Umayyads, who believed that the caliphate was their right after Uthman, and those who wished to restore the caliphate of Quraysh on the same principles laid by Abu Bakr and Umar. This second group was likely the majority within the Quraysh.[213][196] Ali was indeed vocal about the divine and exclusive right of Muhammad's kin to leadership,[220][221] which would have jeopardized the future political ambitions of the rest of the Quraysh.[222]

Administrative policies

Justice

The caliphate of Ali was characterized by his strict justice.[223][224][16] He set out to implement radical policies,[225] which were intended to restore his vision of the prophetic governance.[226][227] The caliph immediately dismissed nearly all of Uthman's governors,[201] whom he considered corrupt.[228] Ali also distributed the treasury funds equally among Muslims, following the practice of Muhammad,[229] and is said to have shown zero tolerance for corruption.[230][231] Some of those affected by Ali's egalitarian policies soon revolted under the pretext of revenge for Uthman.[232] Among them was Mu'awiya, the incumbent governor of Syria.[173] Ali has been criticized for political naivety and excessive rigorism,[7][233] while others believe that Ali ruled with righteousness rather than political expediency.[232][227] His supporters identify similar decisions of Muhammad,[234][235] and assert that Islam never allows for compromising on a just cause, quoting verse 68:9 of the Quran,[235] "They wish that thou might compromise and that they might compromise."[236][237] Some instead suggest that Ali's decisions were actually justified on a practical level.[208][238][16] For instance, the removal of unpopular governors might have been the only option available to Ali because injustice was the main grievance of the rebels.[208]

Religious authority

As evident from his public speeches,[239] Ali viewed himself not only as the temporal leader of the Muslim community but also as its exclusive religious authority.[240][241] He thus laid claim to the religious authority to interpret the Quran and Sunna.[242][243] In return, some supporters of Ali indeed held him as their divinely-guided leader who demanded the same type of loyalty that Muhammad did.[244] These felt an absolute and all-encompassing bond of spiritual loyalty (walaya) to Ali that transcended politics.[245] For instance, a large group of them publicly offered him their unconditional support circa 658.[246][247] They justified their absolute loyalty to Ali on the basis of his merits, precedent in Islam,[248] his kinship with Muhammad,[249] and also the announcement by the latter at the Ghadir Khumm.[245] Many of these supporters also viewed Ali as the rightful successor of Muhammad after his death,[250] as evidenced in the poetry from that period, for instance.[251][252]

Fiscal policies

Ali opposed centralized control over provincial revenues.[206] He also equally distributed the taxes and booty among Muslims,[206][7] following the precedent of Muhammad and Abu Bakr.[253][229] In comparison, Umar had distributed the state revenues according to perceived Islamic merit,[254][255] and Uthman was widely accused of nepotism and corruption.[163][256][164] The strictly egalitarian policies of Ali earned him the support of underprivileged groups, including the Ansar, the qurra, and the late immigrants to Iraq.[219] By contrast, Talha and Zubayr were both Qurayshite companions of Muhammad who had amassed immense wealth under Uthman.[257] They both revolted against Ali when he refused to grant them favors.[258][229] Some other figures among the Quraysh similarly turned against Ali,[259][260] who even rejected a request for public funds by his brother Aqil,[261][262] whereas his archenemy Mu'awiya readily offered bribes.[260][263] Regarding taxation, Ali instructed his officials to collect payments on a voluntary basis and without harassment, and to prioritize the poor when distributing the funds.[264] A letter attributed to Ali directs his governor to pay more attention to land development than taxation.[265][266]

Rules of war

In Islamic jurisprudence, Ali is regarded as an authority on intra-Muslim warfare.[267] During the civil war, he forbade Muslim fighters from looting,[268][269] and instead equally distributed the taxes as salaries among the warriors.[268] With this ruling, Ali thus recognized his enemies' rights as Muslims. He also pardoned them in victory.[269][270] Both of these practices were later enshrined in Islamic law.[269] Ali also advised his commander al-Ashtar not to reject any calls to peace and not to violate any agreements,[271] and warned him against unlawful shedding of blood.[272] He forbade his commanders from disturbing civilians except when lost or in dire need of food.[273] He further urged al-Ashtar to resort to war only when negotiations fail.[274] He also ordered him not to commence hostilities,[274] and this rule Ali observed himself.[275][276] Ali barred his troops from killing the wounded and those who flee, mutilating the dead, entering homes without permission, looting, and harming the women.[277] In particular, he prevented the enslavement of women and children in victory, even though some protested.[7] Before the Battle of Siffin with Mu'awiya, Ali did not retaliate and allowed his enemies to access drinking water when he gained the upper hand.[278][279]

Battle of the Camel

A'isha publicly campaigned against Ali immediately after his accession.[280][201] She was joined in Mecca by her close relatives, Talha and Zubayr,[281] who thus broke their earlier oaths of allegiance to Ali.[213][4][214] This opposition demanded the punishment of Uthman's assassins,[282][185] and accused Ali of complicity in the assassination.[185][213][16] They also called for the removal of Ali from office and for a Qurayshite council to appoint his successor.[201][283] The primary goal of the triumvirate was likely the removal of Ali, rather than vengeance for Uthman,[283][284][285] against whom they had stirred up public opinion.[286][287][288] The opposition failed to gain enough traction in Hejaz,[29][289] and instead captured Basra in Iraq,[4][29] killing many there. In turn, Ali raised an army from nearby Kufa,[286][290] which formed the core of Ali's forces in the coming battles.[290] The two armies soon camped just outside of Basra,[291][16] both numbered around ten thousands men by one account.[292] After three days of failed negotiations,[293] the two sides readied for battle.[293][16][4]

Account of the battle

The battle took place in December 656.[294][295] The rebels commenced hostilities,[286][296] and A'isha was present on the battlefield, riding in an armored palanquin atop a red camel, after which the battle is named.[297][298] Talha was soon killed by another rebel, Marwan, the secretary of Uthman.[299][300] Zubayr, an experienced fighter, deserted shortly after the battle had begun,[296][286] but was pursued and killed.[296][286] His desertion suggests his serious misgivings about the justice of their cause.[301][286] Ali won the day,[286][302][208] and A'isha was escorted back to Hejaz with her due respect.[303][286][294] Ali then announced a public pardon,[304] setting free the war prisoners and prohibiting the enslavement of their women and children. The seized properties were also returned.[305] Ali extended this pardon to high-profile rebels such as Marwan.[306][303] Ali then stationed himself in Kufa,[307] which thus became his de facto capital.[294][285]

Battle of Siffin

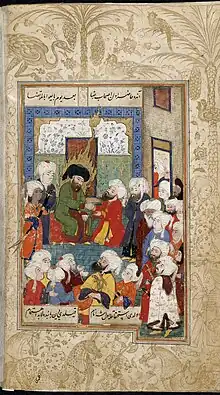

.jpg.webp)

Mu'awiya, the incumbent governor of Syria, was deemed corrupt and unfit by Ali,[228] who wrote to and removed him from his post.[308][309][310] In turn, Mu'awiya, as Uthman's cousin, launched a propaganda campaign across Syria, blaming Ali for the regicide and calling for revenge.[311][312][313] Mu'awiya also joined forces with Amr ibn al-As,[314] a military strategist,[315] who pledged to back the Umayyads against Ali in return for life-long governorship of Egypt.[316] Yet Mu'awiya also secretly offered to recognize the caliphate of Ali in return for Syria and Egypt,[317] which Ali rejected.[318] Mu'awiya then formally declared war on him, charging him with regicide, demanding his removal, and a Syrian council thereafter to elect the next caliph.[319] With some exceptions,[320] contemporary authors view Mu'awiya's call for revenge as a pretext for power grab.[321][241][322][323][320][324]

Account of the battle

In the summer of 657, the armies of Ali and Mu'awiya camped at Siffin, west of the Euphrates River,[325] numbering perhaps at 100,000 and 130,000, respectively.[326] A large number of Muhammad's companions were present in Ali's army, whereas Mu'awiya could only boast a handful.[224][326] The two sides negotiated for a while, to no avail,[185][327][16][328][329] after which the main battle took place from Wednesday, 26 July 657,[324][321] until Friday or Saturday morning.[330][327] Ali probably refrained from initiating hostilities,[208] and later fought alongside his men on the frontline, whereas Mu'awiya led from his pavilion,[331][332] and rejected a proposal to settle the matters in a personal duel with Ali.[333][324][334] Among those killed fighting for Ali was Ammar ibn Yasir, a senior companion of Muhammad.[332] In canonical Sunni sources, a prophetic hadith predicts Ammar's death at the hands of al-fi'a al-baghiya (lit. 'rebellious aggressive group') who call to hellfire.[335][326][327]

Call to arbitration

Fighting stopped when some Syrians raised pages of the Quran on their lances, shouting, "Let the Book of God be the judge between us."[336][327] Since Mu'awiya had for long insisted on battle, this call for arbitration may suggest that he now feared defeat.[336][185][337] By contrast, Ali exhorted his men to fight, telling them that raising the Quran was for deception, but to no avail.[336][324] Through their representatives, the qurra and the ridda tribesmen of Kufa,[338][328][327] the largest bloc in Ali's army,[16][328] both threatened Ali with mutiny if he did not answer the Syrians' call.[336][16][339][340] Facing strong peace sentiments in his army, Ali was thus compelled to accept the arbitration proposal,[341] most likely against his judgment.[327][341]

Arbitration agreement

Mu'awiya now proposed that representatives from both sides should find a solution on the basis of the Quran.[16][342] In Ali's camp, the majority pressed for the neutral Abu Musa, the erstwhile governor of Kufa, despite Ali's opposition.[343][327][344] In turn, Mu'awiya was represented by his ally Amr.[345] The arbitration agreement was written and signed on 2 August 657,[346] stipulating that the two representatives would meet on neutral territory,[347] adhere to the Quran and Sunna, and save the community from war and division.[346][321] Both armies left the battlefield after the agreement.[348] The arbitration agreement thus divided Ali's camp, as many did not support his negotiations with Mu'awiya, whose claims they considered fraudulent. It also strengthened Mu'awiya's position, who was now considered an equal contender for the caliphate.[349]

Formation of the Kharijites

.png.webp)

In protest to the arbitration agreement, some of Ali's men gathered outside of Kufa.[348][208] Many of them eventually rejoined Ali,[350][351][352][7] but the rest moved to the town of al-Nahrawan.[208] These formed the Kharijites (lit. 'seceders'), who later took up arms against Ali in the Battle of Nahrawan.[353][354][16] The Kharijites, many of whom were from the qurra,[355] were probably disillusioned with the arbitration process.[356][16] Their slogan was, "No judgment but that of God,"[321] highlighting their rejection of arbitration (by men) in reference to the Quranic verse 49:9.[357] This Ali called a word of truth by which the seceders sought falsehood, for they were repudiating government even though a ruler was indispensable in the conduct of religion.[358]

Arbitration proceedings

The two arbitrators met together in Dumat al-Jandal,[359] perhaps in February 658.[16] There they reached the verdict that Uthman had been killed wrongfully and that Mu'awiya had the right to seek revenge.[360][361][16] They could not agree on anything else.[362] Rather than a judicial ruling, this was a political concession by Abu Musa, who might have hoped that Amr would later reciprocate this gesture.[362] Ali denounced the conduct of the two arbitrators as contrary to the Quran and began organizing a new expedition to Syria.[363][7] Solely an initiative of Mu'awiya,[360] there was also a second meeting in Udhruh.[360][208] The negotiations there also failed,[363] as the two arbitrators could not agree on the next caliph: Amr supported Mu'awiya,[16] while Abu Musa nominated his son-in-law Abd Allah ibn Umar,[16][364] who stood down.[16][365] At its closure, Abu Musa publicly deposed both Ali and Mu'awiya and called for a council to appoint the new caliph per his earlier agreement with Amr. When Amr took the stage, however, he deposed Ali but confirmed Mu'awiya as the new caliph, thus violating his agreement with Abu Musa.[364][366][16] The Kufan delegation reacted furiously to Abu Musa's concessions,[363] and the common view is that the arbitration failed,[360][343] or was inconclusive.[367][350][368] It nevertheless strengthened the Syrians' support for Mu'awiya and weakened the position of Ali.[360][369][224][16][370]

Battle of Nahrawan

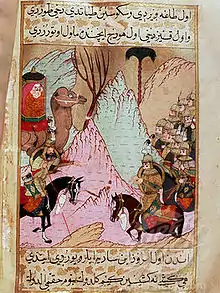

%252C_between_Ali_and_the_Havaric_(Kharijites)._Ali%252C_mounted_on_Duldul%252C_is_wielding_his_double-bladed_sword%252C_Zulfikar._From_a_manuscript_of_Maktel-i_Ali_Resul%252C_Ottoman_Turkey%252C_late_16th_or_early_17th_century.jpg.webp)

After the arbitration, Mu'awiya received the Syrians' pledge as caliph.[371] Ali then prepared for a second confrontation with Mu'awiya,[352][137][372] but with limited success.[29] Around this time, the Kharijites started interrogating civilians about their views on Uthman and Ali, executing those who disagreed with them.[373][374] They subsequently killed many, apparently not even sparing women.[375] Ali received the news of the Kharijites' violence en route to Syria,[376] and moved to Nahrawan with his army.[376] He convinced many of the Kharijites to separate from their army, leaving about 1,500–1,800, or 2,800, out of about 4,000 fighters.[377][378] The rest then attacked and were crushed by Ali's army of about 14,000 men.[379][378] The battle took place either on 17 July 658,[380][352] or in 657.[381][380] Ali has been criticized by some for killing his erstwhile allies,[382][383][384] many of whom were outwardly pious Muslims. For others, subduing the Kharijites was necessary, for they were violent and radicalized rebels who posed a danger to Ali's base in Kufa.[385][386][343][387]

Final years

Following the Battle of Nahrawan, Ali could not muster enough support for a second Syria campaign.[388][384] His soldiers were either demoralized, [383] or perhaps they were recalled by their tribal leaders,[389][390] many of whom had been bribed and swayed by Mu'awiya.[391][390][383] By contrast, Ali did not grant any financial favors to the tribal chiefs as a matter of principle.[259][260] At any rate, the secession of so many of the qurra and the coolness of the tribal leaders weakened Ali.[389][185][392] Ali consequently lost Egypt to Mu'awiya in 658.[366][393] Mu'awiya also began dispatching military units,[366] which targeted civilians along the Euphrates river, near Kufa, and most successfully, in the Hejaz and Yemen.[394] Ali could not mount a timely response to these assaults.[7] He eventually found sufficient support for a second Syria offensive, set to commence in late winter 661. His success was in part due to the public outrage in the wake of the infamous Syrian raids.[395] However, the plans for a second Syria campaign were abandoned after the assassination of Ali.[396]

Assassination and burial

.jpg.webp)

Ali was assassinated during the morning prayer on 28 January 661, equivalent to 19 Ramadan 40 AH. The other given dates are 26 and 30 January. He was struck over his head by the Kharijite Abd al-Rahman ibn Muljam with a poison-coated sword at the Great Mosque of Kufa. Ali died from his wounds about two days later, aged sixty-two or sixty-three. By some accounts, he had long known about his fate either by a premonition or through Muhammad.[397] Ibn Muljam had earlier entered Kufa intending to kill Ali in revenge for the Kharijites' defeat in the Battle of Nahrawan.[398] Before his death, Ali requested either a meticulous application of lex talionis to Ibn Muljam or his pardon. At any rate, he was later executed by Hasan, the eldest son of Ali.[397] Fearing that his body might be exhumed and profaned by his enemies, Ali was then buried secretly.[7] His grave was identified during the caliphate of the Abbasid Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809) and the town of Najaf grew around it near Kufa, which has become a major destination for Shia pilgrimage.[7] The present shrine was built by the Safavid Shah Safi (r. 1629–1642),[399] near which lies an immense cemetery for Shias who wish to be buried next to their imam.[7] Najaf is also home to top religious colleges and prominent Shia scholars.[7][4]

Succession

Shortly after Ali's death, his eldest son Hasan was acknowledged as the next caliph in Kufa.[378][400] As Ali's legatee, Hasan was the obvious choice for Kufans, especially because Ali was vocal about the exclusive right of Muhammad's kin to leadership.[401][400] Most surviving companions of Muhammad were in Ali's army. They also pledged their allegiance to Hasan,[402][403] but overall the Kufans' support for Hasan was likely weak.[404][405] Hasan later abdicated in August 661 to Mu'awiya when the latter marched on Iraq with a large force.[404][405] Mu'awiya thus founded the dynastic Umayyad Caliphate. Throughout his reign, he persecuted the family and supporters of Ali,[406][407] and also mandated regular public cursing of Ali.[406][408]

Descendants of Ali

The first marriage of Ali was with Fatima, who bore him three sons, Hasan, Husayn, and Muhsin.[407] Muhsin either died in infancy,[18] or Fatima miscarried her when she was injured in a raid on her house during the succession crisis.[99] The descendants of Hasan and Husayn are known as the Hasanids and the Husaynids, respectively.[409] These, as the progeny of Muhammad, are honored in Muslim communities by nobility titles such as Sharif and Sayyid.[1] Ali and Fatima also had two daughters, Zaynab and Umm Kulthum.[410] After Fatima's death in 632, Ali remarried multiple times and had more children, including Muhammad al-Awsat and Abbas ibn Ali.[410] In his life, Ali fathered seventeen daughters, and eleven, fourteen, or eighteen sons,[407] among whom, Hasan, Husayn, and Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya played a historical role.[411] Descendants of Ali are known as the Alids.[409]

Under the Umayyads

Upon Ali's assassination, Mu'awiya founded the dynastic Umayyad Caliphate (r. 661–750),[412] during which Alids were severely persecuted.[410] After Ali, his followers (shi'a) recognized his eldest son Hasan as their imam. When he died in 670, perhaps poisoned at the instigation of Mu'awiya,[413][412][414] the Shia community followed his younger brother Husayn, but he and many of his relatives were massacred by Umayyad forces in the Battle of Karbala in 680.[409] To revenge the Karbala massacre, soon followed in 685 the Shia uprising of al-Mukhta'§§r, who claimed to represent Ibn al-Hanafiyya [409] The main movements that followed this uprising were the now-extinct Kaysanites and the Imamites.[415] The Kaysanites mostly followed Abu Hashim, the son of Ibn al-Hanafiya. When Abu Hashim died around 716, this group largely aligned itself with the Abbasids, that is, the descendants of Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib.[409][416] On the other hand, the Imamites were led by quiescent descendants of Husayn through his only surviving son, Ali Zayn al-Abidin (d. 713). An exception was Ali's son Zayd, who led a failed uprising against the Umayyads around 740.[409] For his followers, known as the Zaydites, any learned Hasanid or Husaynid who rose against tyranny qualified as imam.[417]

Under the Abbasids

Alids were also persecuted during the Abbasid Caliphate (r. 750–1258).[409][418] Some of them revolted,[407] while some others took refuge in remote areas and founded regional dynasties.[409][419] Likewise, the Abbasids, through imprisonment or surveillance, removed the quiescent imams of the Imamites from public life.[420][421] The Abbasids are also thought to be responsible for these imams' deaths.[422][423] Mainstream Imamites were the antecedents of the Twelvers,[424] who believe that their twelfth and last imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, was born around 868,[425] but was hidden around 874 for fear of Abbasid persecution. He remains in occultation by divine will until his reappearance at the end of time to eradicate injustice and evil.[426][427] The only historic split among the Imamites happened when of their sixth imam, Ja'far al-Sadiq, died in 765.[409][424] Some claimed that his designated successor was his son Isma'il, who had predeceased al-Sadiq. These were the antecedents of the Isma'ilites,[409] who later found political success:[428] the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt and the Qarmatians in Bahrain, established in 909 and 899, respectively.[429]

Works

Most works attributed to Ali were first delivered in the form of speeches and later committed to writing by others. There are similarly supplications, such as Du'a Kumayl, which he may have taught others.[4]

Nahj al-balagha

Nahj al-balagha (lit. 'the path of eloquence') is an eleventh-century collection of sermons, letters, and sayings, all attributed to Ali, compiled by Sharif al-Radi (d. 1015), a prominent Twelver scholar.[430][431] In view of its sometimes sensitive content, the authenticity of Nahj al-balagha has long been a subject of polemic debates, though, by tracking the texts in sources that predate al-Radi, recent academic research attributes most of its content to Ali.[432][433] The sermons and letters in Nahj al-balagha, particularly the letter of instructions addressed at Malik al-Ashtar,[4] have served as an ideological basis for Islamic governance.[431] The book also includes detailed discussions about social responsibilities, emphasizing that greater responsibilities result in greater rights.[431] Nahj al-balagha also contains sensitive material, such as sharp criticism of Ali's predecessors in its Shaqshaqiya sermon,[4] and disapproval of Aisha, Talha, and Zubayr, who had revolted against Ali.[430][434] Recognized as an example of the most eloquent Arabic,[4] Nahj al-balagha is said to have significantly influenced the Arabic literature and rhetoric.[432] The book has also been the focus of numerous commentaries and studies by both Sunni and Shia authors, including the comprehensive commentary of the Mu'tazilite scholar Ibn Abil-Hadid (d. 1258).[4]

Ghurar al-hikam

Ghurar al-hikam wa durar al-kalim (lit. 'exalted aphorisms and pearls of speech') was compiled by Abd al-Wahid al-Amidi (d. 1116), who was either a Shafi'i jurist or a Twelver scholar. The book consists of over ten thousand short sayings of Ali on piety and ethics.[435][4] These aphorisms and other works attributed to Ali may have considerably influenced the Islamic mysticism.[436]

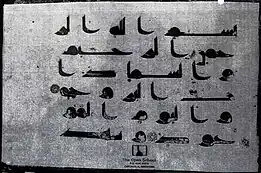

Mushaf of Ali

Mushaf of Ali is a recension of the Quran compiled by Ali, as one of its first scribes.[437] By some Shia accounts, for political reasons, the codex (mushaf) of Ali was rejected for official use after Muhammad's death.[438] Some early Shia traditions also suggest differences with the standard Uthmanid codex,[439] although now the prevalent Shia view is that Ali's recension matches the Uthmanid codex, save for the order of its content.[440] Ali's codex is said to be in the possession of Muhammad al-Mahdi, who would reveal the codex (and its authoritative commentary by Ali) when he reappears.[441][426]

Kitab Ali

Some early traditions point to a collection of prophetic sayings gathered by Ali, known as Kitab Ali (lit. 'book of Ali'), which may have concerned matters of lawfulness (halal) and unlawfulness (haram), including a detailed penal code. Kitab Ali is also often linked to al-Jafr, which is said to contain the esoteric teachings of Muhammad for his household.[442][443] Copies of Kitab Ali were likely available until the early eighth century, and parts of it have survived in later Shia and Sunni works.[444]

Other works

The Du'a' Kumayl is a popular Shia supplication attributed to Ali, transmitted on the authority of his companion, Kumayl ibn Ziyad.[4][445] Also attributed to Ali is Kitab al-Diyat on Islamic law, quoted in the hadith collection Man la yahduruhu al-faqih by the Shia traditionist Ibn Babawayh (d. 991).[446] The judicial decisions and executive orders of Ali during his caliphate have also been recorded.[447] Other extant works attributed to Ali are collected in Kitab al-Kafi of the Shia traditionist al-Kulayni (d. 941) and other works of Ibn Babawayh.[4]

Contributions to Islamic sciences

The standard recitation of the Quran has been traced back to Ali,[448][449][224] and his written legacy is dotted with Quranic commentaries.[444] Ibn Abbas, a leading early exegete, credited Ali with his interpretations of the Quran.[450] Ali has also related several hundred prophetic hadiths.[444] Ali is furthered credited with the first systematic evaluations of hadiths, and is often considered a founding figure for hadith sciences.[444] Ali is also regarded by some as the founder of Islamic theology, and his sayings contain the first rational proofs among Muslims of the unity of God (tawhid).[451][37] In later Islamic philosophy, Ali's sayings and sermons were mined for metaphysical knowledge.[1] In particular, Nahj al-balagha is a vital source for Shia philosophical doctrines, after the Quran and the Sunna.[452] As a Shia imam, statements and practices attributed to Ali are widely studied in Shia Islam, where they are viewed as the continuation of prophetic teachings.[444]

Character

Ali | |

|---|---|

| |

| Venerated in | Islam[lower-alpha 14] Baháʼí Faith Yarsanism |

| Major shrine | Imam Ali Shrine, Najaf |

Often praised for his piety and courage,[224][453][7] he fought to uphold his beliefs,[7][454] but was also magnanimous in victory,[455][224] even risking the ire of some supporters to prevent the enslavement of women and children.[7] He also showed his grief, wept for the dead, and reportedly prayed over his enemies.[7] Yet Ali has also been criticized for his idealism and political inflexibility,[7][233] for his egalitarian policies and strict justice antagonized many.[456][232] Or perhaps these qualities were also present in Muhammad,[235][234] whom the Quran addresses as, "They wish that thou [Muhammad] might compromise and that they might compromise."[457] At any rate, most seem to agree that these qualities of Ali, rooted in his religious beliefs, contributed to his image for his followers today as a paragon of Islamic virtues,[458][459][456] particularly justice.[460] Ali is also viewed as the model par excellence for Islamic chivalry (futuwwa).[461][462][463]

Historical accounts about Ali are often tendentious.[411] For instance, in person, Ali is described in some Sunni sources as bald, heavy-built, short-legged, with broad shoulders, hairy body, long white beard, and affected by eye inflammation.[7] Shia accounts about the appearance of Ali are markedly different. Those perhaps better match his reputation as a capable warrior.[464] Likewise, in manner, Ali is presented in some Sunni sources as rough, brusque, and unsociable.[7] By contrast, Shia sources describe him as generous, gentle, and cheerful,[462][460] to the point that the Syrian war propaganda accused him of frivolity.[230] Shia and Sufi sources are also replete with reports about his acts of kindness, especially to the poor.[465] The necessary qualities in a commander, described in a letter attributed to Ali, may have well been a portrait of himself: slow to anger, happy to pardon, kind to the weak, and severe with the strong.[466] His companion, Sa'sa'a ibn Suhan, described him similarly, "He [Ali] was amongst us as one of us, of gentle disposition, intense humility, leading with a light touch, even though we were in awe of him with the kind of awe that a bound prisoner has before one who holds a sword over his head."[460][466]

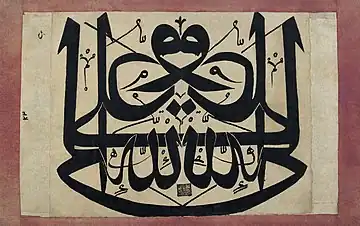

Names and titles

Ali is known by many titles and honorifics in the Islamic tradition, some of which are exclusively found in Shia literature. His titles include Abu al-Hasan (lit. 'father of Hasan'),[3][1] al-Murtada (lit. 'one with whom [God] is pleased'),[3] Asad Allah (lit. 'lion of God'),[467] Haydar (lit. 'lion', the name initially her mother gave him),[3] and Amir al-Mu'minin (lit. 'commander of the faithful'), Imam al-Muttaqin (lit. 'leader of the God-fearing'), Wali Allah (lit. 'friend of God').[3] In particular, Twelvers consider the title of Amir al-Mu'minin to be unique to Ali.[468] He is also referred to as Abu Turab (lit. 'father of dust'),[1] which might have initially been a pejorative by his enemies.[7]

Place in Islam

Ali's place in Muslim culture is said to be second only to Muhammad.[16] More has been written about him in Islamic literature than anyone else, except Muhammad.[1] Ali is revered for his courage, honesty, unbending devotion to Islam, magnanimity, and equal treatment of all Muslims.[455] For his admirers, Ali has thus become the archetype of un-corrupted Islam and pre-Islamic chivalry.[459]

In the Quran

Ali regularly represented Muhammad in missions that were preceded or followed by Quranic injunctions.[469][470] Some verses of the Quran were therefore revealed in connection to Ali.[469] For instance, the verse of walaya (5:55) is a reference to when Ali gave his ring to a beggar, while praying in the mosque, by Shia and some Sunni accounts.[471] If so, then this verse gives Ali the same spiritual authority (walaya) as Muhammad.[472][473] In Shia sources, the verse of tabligh (5:67) spurred Muhammad to designate Ali as his successor at the Ghadir Khumm, while the verse of ikmal al-din (5:3) subsequently announced the perfection of Islam.[474] The verse of purification (33:33) concerns the status of purity of the Ahl al-Bayt (lit. 'people of the house'), which is limited to Ali, Fatima, and their two sons in Shia and some Sunni sources.[475][476][477] Another reference to the Ahl al-Bayt might be the verse of mawadda (42:23).[478][479][480] This verse, especially for Shia Muslims, is a Quranic mandate to love and follow the Ahl al-Bayt.[481][478]

In hadith literature

Numerous sound traditions, attributed to Muhammad, praise the qualities of Ali. The most controversial such statement, "He whose mawla I am, Ali is his mawla," was delivered at the Ghadir Khumm in 632. This gave Ali the same spiritual authority (walaya) as Muhammad, according to the Shia.[482] Elsewhere, the hadith of the position likens Muhammad and Ali to Moses and Aaron,[38] and thus supports the usurped right of Ali to succeed Muhammad in Shia Islam.[483] Other examples in standard Shia and Sunni collections of hadith include, "There is no youth braver than Ali," "No-one but a believer loves Ali, and no-one but a hypocrite (munafiq) hates Ali," "I am from Ali, and Ali is from me, and he is the wali (lit. 'patron' or 'guardian') of every believer after me," "The truth revolves around him [Ali] wherever he goes," "I am the city of knowledge and Ali is its gate (bab)," "Ali is with the Quran and the Quran is with Ali. They will not separate until they return to me at the [paradisal] pool."[484][37]

In Sunni Islam

In Sunni Islam, Ali is venerated as a close companion of Muhammad,[485] a foremost authority on the Quran and Islamic law,[450][486] and the fountainhead of wisdom in Sunni spirituality.[487] When the prophet died in 632, Ali had his own claims to leadership, perhaps in reference to the prophet's announcement at the Ghadir Khumm,[115][488] but he eventually accepted the temporal rule of the first three caliphs in the interest of Muslim unity.[489] Ali is portrayed in Sunni sources as a trusted advisor of the first three caliphs,[1][490] while their conflicts with Ali are neutralized,[127][491] in line with the Sunni tendency to show accord among companions.[128][492][493] As the fourth and final Rashidun caliph, Ali is held in a particularly high status in Sunni Islam, although this doctrinal reverence for Ali is a recent development in Sunni Islam for which the prominent traditionist Ahmad ibn Hanbal is likely to be credited.[4] His hierarchy of companions places Ali above those companions who fought against him, thus accommodating into Sunni doctrine the opposite sides of a moral conflict that has split the Muslim community ever since. But this Sunni hierarchy also places Ali below his predecessors,[4][494][485] which has required the reinterpretation of those prophetic sayings that explicitly elevate Ali above other companions.[4]

In Shia Islam

Ali takes center stage in Shia Islam,[1] for the Arabic word shi'a itself is short for shi'a of Ali (lit. 'followers of Ali'),[495] his name is incorporated into the daily Shia call to prayer,[1] and he is regarded as the foremost companion of Muhammad.[496][497] The defining doctrine of Shia Islam is that Ali was the rightful successor of Muhammad through divinely-ordained designation,[490][498] which is primarily a reference to the Ghadir Khumm.[499] Ali is thought to have inherited the political and religious authority of Muhammad, even before his ascension to the caliphate in 656.[500][501] The Shia community has therefore largely considered Ali's predecessors as illegitimate rulers and usurpers of his rights.[490] The all-encompassing bond of loyalty between Shia Muslims and their imams (and Muhammad in his capacity as imam) is known as walaya.[245] Ali is also thought to be endowed with the privilege of intercession on the Judgment Day.[4] Early on, some Shias even attributed divinity to Ali,[490][496] although such extreme views were rooted out of Shi'ism through the efforts of Ali's successors.[502]

In Shia belief, Ali also inherited the esoteric knowledge of Muhammad,[503][504] for instance, in view of the prophetic hadith, "I [Muhammad] am the city of knowledge, and Ali is its gate."[503] Ali is thus regarded, after Muhammad, as the interpreter, par excellence, of the Quran and the sole authoritative source of its (esoteric) teachings.[499] Unlike Muhammad, however, Ali is not thought to have received divine revelation (wahy), though he might have been guided by divine inspiration (ilham).[500][505] Verse 21:73 of the Quran is sometimes cited here, "We made them imams, guiding by Our command, and We revealed (awhayna') to them the performance of good deeds, the maintenance of prayers, and the giving of zakat (alms), and they used to worship Us."[506] Shia Muslims also believe in the infallibility of Ali, as with Muhammad, that is, their divine protection from sins.[4][507] Here, the verse of purification is sometimes cited.[508][509] Ali's words and deeds are therefore considered a model for the Shia community and a source for their religious injunctions.[510][511]

In Sufism

Ali is the spiritual head of some Sufi movements,[4] for Sufis believe that he inherited from Muhammad his saintly authority (walaya),[1] which assists believers on their journey toward God.[4] Nearly all Sufi orders trace their lineage to Muhammad through Ali, an exception being the Naqshbandis, who reach Muhammad through Abu Bakr.[1]

Historiography

Much has been written about Ali in historical texts, second only to Muhammad, according to Nasr and Afsaruddin. The primary sources for scholarship on the life of Ali are the Qur'an and hadiths, as well as other texts of early Islamic history. The extensive secondary sources include, in addition to works by Sunni and Shia Muslims, writings by Arab Christians, Hindus, and other non-Muslims from the Middle East and Asia and a few works by modern western scholars.[1] Since the character of Ali is of religious, political, jurisprudential, and spiritual importance to Muslims (both Shia and Sunni), his life has been analyzed and interpreted in various ways.[4] In particular, many of the Islamic sources are colored to some extent by a positive or negative bias towards Ali.[1]

The earlier Western scholars, such as Caetani (d. 1935), were often inclined to dismiss as fabricated the narrations and reports gathered in later periods because the authors of these reports often advanced their own Sunni or Shia partisan views. For instance, Caetani considered the later attribution of historical reports to Ibn Abbas and A'isha as mostly fictitious since the former was often for and the latter was often against Ali. Caetani instead preferred accounts reported without isnad by the early compilers of history like Ibn Ishaq. Madelung, however, argues that Caetani's approach was inconsistent and rejects the indiscriminate dismissal of late reports. In Madelung's approach, tendentiousness of a report alone does not imply fabrication. Instead, Madelung and some later historians advocate for discerning the authenticity of historical reports on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures.[512]

Until the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate, few books were written and most of the reports had been oral. The most notable work prior to this period is the Book of Sulaym ibn Qays, attributed to a companion of Ali who lived before the Abbasids.[513] When affordable paper was introduced to Muslim society, numerous monographs were written between 750 and 950. For instance, according to Robinson, at least twenty-one separate monographs were composed on the Battle of Siffin in this period, thirteen of which were authored by the renowned historian Abu Mikhnaf. Most of these monographs are, however, not extant anymore except for a few which have been incorporated in later works such as History of the Prophets and Kings by Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (d. 923).[514] More broadly, ninth- and tenth-century historians collected, selected, and arranged the available monographs.

See also

Notes

- ↑ English: Commander of Faithful

- ↑ Especially among the Shia Muslims

- ↑ English: Father of Dust

- ↑ English: Father of Hasan

- ↑ English: Gate to the City of Knowledge

- ↑ English: One who is Chosen and Contented

- ↑ English: Master of the God-Fearing

- ↑ Especially among the Shia Muslims

- ↑ English: Lion

- ↑ English: Lion of God

- ↑ English: Friend of God

- ↑ Especially among the Shia Muslims

- ↑ Ali's nasab was Ali ibn Abi Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib ibn Hashim ibn Abd Manaf ibn Qusai ibn Kilab.

- ↑ All Muslims venerate Ali as a prominent companion of Muhammad and caliph. Shia Muslims and Alevis considered him as successor of Muhammad, the Alawites also consiered Ali as the physical manifestation of God.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Nasr & Afsaruddin 2022.

- ↑ Öz 1989, pp. 392–393.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Haj Manouchehri 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Gleave 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Shah-Kazemi 2015.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 239.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Veccia Vaglieri 1960.

- ↑ Watt 1953, p. 86.

- ↑ Watt 1986.

- ↑ Rubin 1995, p. 130.

- 1 2 3 Momen 1985, p. 12.

- ↑ Rubin 1995, pp. 136–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Huart 2022.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 71, 98.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, pp. 46, 206.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Poonawala 2011.

- ↑ Kassam & Blomfield 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Buehler 2014, p. 186.

- ↑ Bodley 1946, p. 147.

- ↑ Klemm 2005, p. 186.

- ↑ Qutbuddin 2006, p. 248.

- ↑ Momen 1985, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 Schmucker 2012.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 16.

- 1 2 Osman 2015, p. 110.

- ↑ Nasr et al. 2015, p. 379.

- ↑ Haider 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ Haider 2014, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 Iranica 2011.

- ↑ McAuliffe.

- ↑ Fedele 2018, p. 56.

- ↑ Lalani 2006, p. 29.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 72.

- ↑ Bill & Williams 2002, p. 29.

- 1 2 Momen 1985, p. 13.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 Shah-Kazemi 2014.

- 1 2 Miskinzoda 2015, p. 69.

- ↑ Miskinzoda 2015, pp. 76–7.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 46.

- ↑ Faizer 2006.

- ↑ Donner 2010, pp. 72–3.

- ↑ Arafat 1976.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, pp. 34–9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Veccia Vaglieri 2022.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, pp. 34–7.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 2012.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 15.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Amir-Moezzi 2022.

- ↑ Campo 2009.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 79.

- ↑ Wain & Hashim Kamali 2017, p. 12.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 20.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 35.

- 1 2 Lalani 2011.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 20.

- 1 2 Dakake 2008, p. 45.

- ↑ Afsaruddin 2006.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 2.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 47.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 21.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 70.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 46.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, pp. 44–5.

- ↑ Lalani 2006, p. 590.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 253.

- ↑ McHugo 2018, §2.IV.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 41.

- 1 2 Afsaruddin 2013, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 4 Jafri 1979, p. 39.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 18.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 30–2.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 37.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 35.

- ↑ Momen 1985, pp. 18–9.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 36, 40.

- ↑ McHugo 2018, §1.III.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 5.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 34.

- ↑ Afsaruddin 2013, p. 185.

- ↑ Keaney 2021, §3.1.

- 1 2 Walker 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ Lecomte 2022.

- ↑ Shaban 1971, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Madelung 1997, p. 43.

- ↑ Khetia 2013, pp. 31–2.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 32.

- 1 2 Fedele 2018.

- 1 2 Jafri 1979, p. 40.

- ↑ Qutbuddin 2006, p. 249.

- ↑ Cortese & Calderini 2006, p. 8.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 41.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, pp. 43–4.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, pp. 40–1.

- ↑ Soufi 1997, p. 86.

- 1 2 Khetia 2013, p. 78.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 98.

- ↑ Soufi 1997, pp. 84–5.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, pp. 17–20.

- ↑ Khetia 2013, p. 35.

- ↑ Soufi 1997, p. 84.

- ↑ Khetia 2013, p. 38.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 47.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 50.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 116.

- ↑ Soufi 1997, pp. 104–105.

- 1 2 Sajjadi 2021.

- ↑ Veccia Vaglieri 2012c.

- ↑ Soufi 1997, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 4 Madelung 1997, p. 141.

- 1 2 Jafri 1979, p. 44.

- 1 2 Momen 1985, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ McHugo 2018, p. 40.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 141, 253.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 113–114.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 62.

- 1 2 Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 79.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, pp. 114, 117.

- 1 2 3 Anthony 2013.

- 1 2 Mavani 2013, p. 117.

- ↑ Aslan 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 42, 52–54, 213–4.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 Jafri 1979, p. 45.

- 1 2 Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 78.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 81.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 50.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, pp. 47–8.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Veccia Vaglieri 1960, p. 382.

- ↑ Afsaruddin 2013, p. 32.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 32.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 46.

- 1 2 Glassé 2001, p. 40.

- ↑ Tabatabai 1979, p. 158.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 16.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 89.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 22.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 66–7.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 62, 65.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 67.

- ↑ Pellat 2011.

- 1 2 Jafri 1979, p. 50.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 52.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 43.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 71.

- 1 2 3 Jafri 1979, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 4 Momen 1985, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Jafri 1979, p. 54.

- ↑ Kennedy 2015, p. 60.

- ↑ Bodley 1946, p. 348.

- ↑ Keaney 2021, §3.4.

- ↑ Shaban 1971, pp. 62–3.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 71–2.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, pp. 52–3.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 116.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 68.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, pp. 52–53, 55.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 87.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 1970, p. 67.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 84.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 52.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 108, 113.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 53.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 108.

- 1 2 3 4 Hinds 1972a, p. 467.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Jafri 1979, p. 63.

- 1 2 Daftary 2014, p. 30.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 98.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 100–2.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 59.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 107–8.

- 1 2 3 4 Momen 1985, p. 22.

- 1 2 Jafri 1979, p. 62.

- 1 2 McHugo 2018, p. 49.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 121.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 118–9.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 128.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Anthony 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Veccia Vaglieri 1970, p. 68.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 111, 119.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 122.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 4 Madelung 1997, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Madelung 1997, p. 127.

- 1 2 Levi Della Vida & Khoury 2012.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 126.

- ↑ Hinds 1972a.

- ↑ Donner 2010, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 Kennedy 2015, p. 65.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 2021b.

- 1 2 3 Donner 2010, p. 157.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. §3.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Donner 2010, p. 158.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 28.

- ↑ Wellhausen 1927, p. 49.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 1970, p. 69.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 Lapidus 2002, p. 56.

- 1 2 3 Ayoub 2014, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bahramian 2015.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, pp. 142–3.

- 1 2 3 Momen 1985, p. 24.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 70.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 Madelung 1997, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Jafri 1979, p. 64.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 144–5.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 144.

- 1 2 Shaban 1971, p. 71.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 85.

- 1 2 Shaban 1971, p. 72.

- ↑ Keaney 2021, §3.5.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 72.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 115.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 309–10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Momen 1985, p. 25.

- ↑ Tabatabai 1979, p. 43.

- ↑ McHugo 2018, p. 53.

- 1 2 Ayoub 2014, p. 91.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 Tabatabai 1979, p. 45.

- 1 2 Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 105.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 272.

- 1 2 3 Tabatabai 1979, p. 44.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, pp. 149–50.

- 1 2 Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 Tabatabai 1979, p. 46.

- ↑ Tabatabai 1979, p. 64.

- ↑ Nasr et al. 2015, p. 3203.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 150.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 77.

- 1 2 Shaban 1971, p. 73.

- ↑ Shaban 1971, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Haider 2014, p. 34.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 60.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 59.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 71.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 262n30.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 67.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 133.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 90.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 83.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, pp. 84, 90.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, pp. 55–6.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 94.

- 1 2 Ayoub 2014, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 McHugo 2018, p. 64.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 264.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, pp. 105–6.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 276.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 153.

- ↑ Lambton 1991, pp. xix, xx.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 156.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 114.

- 1 2 Heck 2004.

- 1 2 3 Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 94.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 84.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 115.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 116.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 108.

- 1 2 Ayoub 2014, p. 109.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 170, 260.

- ↑ Kelsay 1993, p. 67.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, pp. 109–10.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 227.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, pp. 111–2.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 89.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 133.

- ↑ Cappucci 2014, p. 19.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 157.

- ↑ Aslan 2011, p. 132.

- 1 2 McHugo 2018, §2.II.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Veccia Vaglieri 1991.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 98, 101, 107.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 88.

- ↑ Veccia Vaglieri 1960, p. 383.

- 1 2 Hinds 1971, p. 361.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 166.

- ↑ Hazleton 2009, p. 107.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Donner 2010, p. 159.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 169–70.

- 1 2 3 Madelung 1997, p. 170.

- ↑ Hazleton 2009, p. 113.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 139.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 171–2.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 140.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 171.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 172.

- 1 2 Abbas 2021, p. 141.

- ↑ Hazleton 2009, p. 121.

- ↑ Hazleton 2009, p. 122.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 180-1.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 182.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 194.

- ↑ Petersen 1958, p. 165.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 97.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 190.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 144.

- ↑ Rahman 1989, p. 58.

- ↑ Donner 2010, p. 160.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 99.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 196.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 203.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 204.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 204–205.

- 1 2 Kennedy 2015, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 Shah-Kazemi 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, pp. 95–6.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 4 McHugo 2018, 2.III.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 226.

- 1 2 3 Lecker 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Donner 2010, p. 161.

- 1 2 3 Shaban 1971, p. 75.

- ↑ Kennedy 2015, p. 67.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 232.

- ↑ Hazleton 2009, p. 198.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 234.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 235.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 119.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 Madelung 1997, p. 238.

- ↑ Adamec 2016, p. 406.

- ↑ Veccia Vaglieri 1970, p. 70.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, pp. 123–4.

- ↑ Hinds 1972b, p. 97.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 241.

- ↑ Hinds 1972b, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 Afsaruddin 2013, p. 53.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 241–2.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 243.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 1.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 247.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 245.

- 1 2 Feisal 2007, p. 191.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 248–9.

- 1 2 3 Donner 2010, p. 163.

- ↑ Levi Della Vida 2012.

- ↑ Donner 2010, p. 162.

- ↑ Hinds 1972b, p. 100.

- ↑ Hinds 1972b, p. 101.

- ↑ Feisal 2007, pp. 190–1.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 249–50.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Madelung 1997, p. 255.

- ↑ Aslan 2011, p. 137.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 256.

- 1 2 3 Madelung 1997, p. 257.

- 1 2 Glassé 2001a, p. 40.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 286.

- 1 2 3 Donner 2010, p. 165.

- ↑ Fadel 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Hinds 1972b, p. 102.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 65.

- ↑ Daftary 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 257–8.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 255, 257.

- ↑ Wellhausen 1901, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 254.

- ↑ Levi Della Vida 1978.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, pp. 259–60.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 260.

- 1 2 3 Wellhausen 1901, p. 18.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 259–261.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, pp. 260–1.

- ↑ Wellhausen 1927, p. 85.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, pp. 141, 171.

- 1 2 3 Donner 2010, p. 164.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 262.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 261.

- ↑ Kelsay 1993, p. 87.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, pp. 97–8.

- ↑ Ayoub 2014, p. 141.

- 1 2 Shaban 1971, p. 77.

- 1 2 Jafri 1979, p. 123.

- ↑ Kennedy 2015, p. 68.

- ↑ Kennedy 2015, p. 69.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 268–9.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, pp. 262, 288–291, 293.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 307.

- ↑ Donner 2010, p. 166.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 1986.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 308.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 26.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 1971.

- ↑ Madelung 1997, p. 311.

- ↑ Momen 1985, pp. 26–7.

- ↑ Jafri 1979, p. 91.

- 1 2 Momen 1985, p. 27.

- 1 2 Jafri 1979, pp. 109–10.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 334.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis 2012.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, pp. 67, 78.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Daftary 2014.

- 1 2 3 Huart 2012.

- 1 2 Veccia Vaglieri 1960, p. 385.

- 1 2 Madelung 2003.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 28.

- ↑ Anthony 2013, p. 216.

- ↑ McHugo 2018, p. 104.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 69.

- ↑ Momen 1985, pp. 49, 50.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 71.

- ↑ Donner 1999, p. 26.

- ↑ Sachedina 1981, p. 25.

- ↑ Dakake 2007, p. 211.

- ↑ Pierce 2016, p. 44.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 44.

- 1 2 McHugo 2018, p. 107.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 161.

- 1 2 Amir-Moezzi 1998.

- ↑ McHugo 2018, p. 108.

- ↑ Haider 2014, p. 92.

- ↑ Daftary 2007, pp. 2, 110, 128.

- 1 2 Thomas 2008.

- 1 2 3 Esposito 2003, p. 227.

- 1 2 Shah-Kazemi 2006.

- ↑ Djebli 2012.

- ↑ Dakake 2008, p. 225.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ Jozi & Shah-Kazemi 2015.

- ↑ Modarressi 2003, p. 2.

- ↑ Modarressi 1993, p. 13.

- ↑ Amir-Moezzi 2009, p. 24.

- ↑ Momen 1985, pp. 77, 81.

- ↑ Amir-Moezzi 1994, p. 89.

- ↑ Esposito 2003, pp. 175–176.

- ↑ Modarressi 2003, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pakatchi 2015.

- ↑ Chittick 1990, p. 42.

- ↑ Modarressi 2003, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Modarressi 2003, p. 17.

- ↑ Modarressi 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ Hulmes 2008, p. 45.

- 1 2 Lalani 2006, p. 28.

- ↑ Nasr 2006, pp. 2, 120.

- ↑ Corbin 2006, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 72.

- ↑ Steigerwald 2004.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, pp. 309–310.

- 1 2 Ayoub 2014, p. 134.

- ↑ Tabatabai 1979, pp. 46, 64.

- ↑ Veccia Vaglieri 1960, p. 386.

- 1 2 Madelung 1997, p. 310.

- 1 2 3 Haj Manouchehri 2022.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2007, p. 189n1.

- 1 2 Glassé 2001, p. 41.

- ↑ Momen 1985, p. 90.

- ↑ Abbas 2021, p. 63.

- ↑ Shah-Kazemi 2022, pp. 35–36.

- 1 2 Shah-Kazemi 2022, p. 104.

- ↑ Alizadeh 2015.

- ↑ Gibb 1986.

- 1 2 Lalani 2006.

- ↑ Momen 1985, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Nasr et al. 2015, p. 706.

- ↑ Nasr et al. 2015, p. 706-7.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, p. 46.

- ↑ Mavani 2013, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Momen 1985, pp. 16, 17.

- ↑ Leaman 2006.